Since the human body tends to move in the direction of its expectations, plus or minus, it is important to know that attitudes of confidence and determination are no less a part of the treatment program than medical science and technology.

Norman Cousin (1979)

Introduction

Diabetes education is probably the most common activity that occurs in diabetes centres. Yet much of the literature about diabetes education driven out of empowerment work refers to diabetes education as more art than science. The Art of Empowerment by Anderson (2000) is just one example of the books that focus on diabetes education and care as an art, rather than science. However, the emphasis on the art of diabetes education is only one side of the coin. There is an abundance of research with Anderson’s colleagues on one side and a plethora of medical texts about diabetes pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment on the other side. I suggest the point of the tension between these two positions is probably the space where the proponents of science and art meet, converge and have some productive conversations over a glass of red wine.

I hope this chapter will meet you at the point of convergence; but I will be talking from the science side of the fence, for no other reason than I am a psychologist trained as a scientist not an artist. One of my research passions is to inform the practice of diabetes care, education and support from a position of empiricism. Likewise, I am an inherent sceptic, which makes me do quite well at critical analysis of research, but generally makes rather inept at appraising art.

The other perspective I bring to the chapter is not scientific: it is the lens I bring as a person. I am a great believer in making these lenses explicit, in the hope that the reader, using a different lens, can see what is inherently useful in what I write, and what is just a function of the lens I am wearing at particular places in the chapter. The two lenses currently tinting my thinking share many similarities and yet appear quite disparate: the lens of Soto Zen Buddhism and the Argentine Tango. The things that unite these views are the richness obtained from simplicity, from being in the present moment and connecting with the unique expression of one’s self.

The emphasis is on being fully present, whether mediating alone, or entwined in the dialogue of passionate tango. These are the key to diabetes education regardless of whether you are an artist or a scientist, or sit at the intersection of the two; high quality diabetes education means being completely present in the interaction in mind and body.

Given this preamble, which I hope has been somewhat more entertaining or informative than I usually read in text books, I plan to consider three issues that I hope will help you reflect on the way you think about and deliver diabetes education. The first reflection concerns the nature of the goals people have and how goals shape decision-making. The second concerns the implications of some recent research on people’s ability to resist temptation. Third, I will draw attention to an issue of increasing interest to me, both in terms of the physiological effects and what it means for education—the impact of sleep, or lack of it.

Why don’t people do what is best for them?

The first area to consider is decision-making, or as one colleague said at a recent conference, ‘it is amazing how many people do stupid things’. I chose not to enter into a debate with him about this throwaway line, because it sums up one common misconception that abounds in diabetes care—people do not do what clinicians think is good for them, and make what clinicians consider to be stupid decisions. I do not subscribe to such a view. In fact, I think this mindset or attitude is actually a barrier to providing effective diabetes care and education. It is based on the premise that if people are not doing what clinicians deem the appropriate thing to do (what is best for them) there is something wrong with them.

In contrast, one of my core philosophies that underpins all my work, although sometimes I forget and appear quite arrogant and condescending, so I am told, is that every individual with intact mental faculties, which excludes people with psychosis, mental disabilities and politicians, make decisions to optimise their quality of life according to their perception of their situation.

When I put this point of view forward at workshops and seminars, I am always stunned at the controversy it causes for many people. Thus, I choose to explore or expand on part of the issue in this chapter. The issue is fundamental to helping health professionals (HPs) understand their clients, support them and provide them with the tools and information they need to make informed decisions about their diabetes.

When I say ‘informed decisions’, I want to be clear, that I do not mean the decision, I, or any other HP, carer, friend or politician wants the individual to make. I mean exactly what I say. The individual makes an informed decision. Clinicians often assume that if they provide people with information about their diabetes, its management and the likely consequences of different actions, people with diabetes will be empowered to make informed decisions, on the understanding that people make choices, and continue to make choices each day, as they live with their diabetes. That is not what I mean by making informed decisions.

First, we have to ask whether the way we provide information to people with diabetes is done in a way that ensures they understand the information. There is sufficient research to indicate that much of the way HPs ‘inform’ people about their diabetes does not facilitate understanding, or even recall. Even the information leaflets and web pages we develop are not readable by or comprehensible to the vast majority of people with diabetes, or even some HPs (Petterson et al. 1994; Harwood and Harrison 2004; Boulos 2005).

However, that is not the main point: clinicians usually think an informed decision results in the person making the dietary changes the HP wants them to make or being more physically active, or taking their medication. Actually, just making recommended changes is not necessarily informed decision-making. An informed decision is based on the person considering their understanding of diabetes, regardless of whether their understanding is erroneous or not, their understanding of other aspects of their life, and their values before they decide what to do.

Thus, an individual may know that it is ‘better to eat a healthy diet’ but be constrained by the cost of fresh food or their family may be unwilling to eat it, and decide to continue to buy cheaper highly processed high fat food. That is an informed choice. Therefore, an informed decision is a decision where the person acts on their understanding of the information provided to them or they source for themselves, and it means the choice can be reviewed at another time. People make decisions according to what they believe will optimise their quality of life, given their perception of their situation at the time the decision is made. Thus, in the scenario described, the individual decided to continue to eat a less healthy diet for the quality of life benefits that come from managing a demanding home environment in the way that causes the least aggravation.

The key message for HPs is to understand why some people make choices that do not seem to be designed to optimise their quality of life. Common scenarios that HPs could reflect on include:

- Why do some girls consciously choose not to inject their insulin to manipulate their weight?

- Why do some people behave in ways they know will prevent their foot ulcers from healing and could lead to an amputation?

As I strived to understand people’s decision-making from a scientist’s perspective, I found the writings of two American psychologists, Carver and Scheier, very informative.

Self-regulation, goals and values

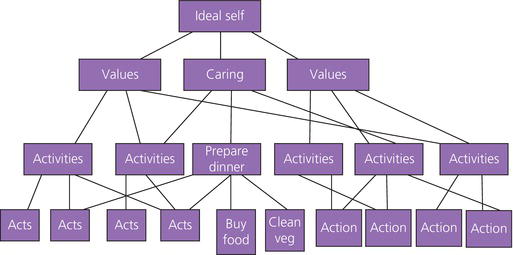

Carver and Scheier (2001) suggested the key to understanding people’s decision-making about everyday behaviours is to understand their values and/or goals. These goals form hierarchical structures (Figure 4.1). Everyday behaviours such as preparing food and walking the dog are referred to as ‘do’ goals, serving higher order goals such as being a loving partner are referred to as be goals, and possibly higher goals related to core values that people hold as images of the ideal self.

The implication of Carver and Scheier’s (2001) approach to behaviour being goal-orientated, is that, to understand the behaviours individuals undertake and their decision-making, HPs need to understand what the individual’s goals are, and possibly more importantly the goals the behaviours are serving. Although many goals may be common to many people, each person has a different set of goals and values. Many people are not aware of their goals, because they were adopted without conscious effort through education, socialisation and culture. In addition, many goals are shared goals, for example to be healthy, liked or rich, although the importance of each goal may be different for each individual. However, other goals are relatively uncommon, or even unique to an individual. Therefore, each person has an individual goal system, which is unique to them.

Understanding peoples’ values or goals can help HPs understand why people make some of the choices they make. For example, a former female military officer I counselled struggled to lose weight, get fit and be healthy and successful, because she always seemed to sabotage her own efforts. When I took time to explore the issues with her, we both began to understand that she had developed a goal to be unattractive to avoid sexual harassment.

The goal subconsciously developed over several years as she suffered unpleasant harassment in one particular military establishment. It took a great deal of effort for her to realise she had not consciously set out to make herself unattractive by being overweight. Thus, her eating and sabotaging her efforts to manage her weight made perfect sense in the context of this unconscious goal. Becoming aware of the issue enabled her to drop the goal and discontinue behaviours that serviced the goal. I am not suggesting that diabetes education should involve delving into peoples goals, but appreciating that each individual has competing sets of goals, and understanding the individual may not be aware of some goals could help HPs be less judgemental of other peoples’ behaviour.

Behaviour-serving goals

If people have a set of internal goals, many of which may be competing with each other, how do they decide, consciously or otherwise, which goals have greater priority and are enacted? When I say ‘decide’, I am not necessarily referring to a conscious process. Many daily decisions are not consciously made, and it takes a lot of effort to bring them to awareness. For instance, I still find it exceptionally difficult to only eat one or two chocolate digestive biscuits or chocolate hob-nobs. If I have one, it takes an exceptional degree of effort of will not to eat the whole packet. I do not know why this is so, and I do not know what triggers the need to eat the whole packet of biscuits. My non-conscious mind periodically overrides my conscious goals. If other HPs are truly honest with themselves, they will be able to identify similar behaviours in themselves. Thus, it should be no great surprise that the same kind of thing happens to many people on a regular basis.

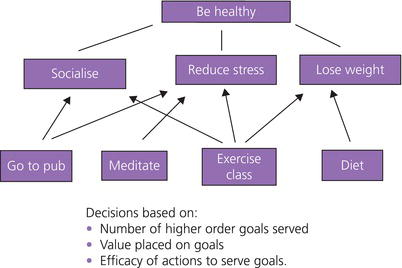

One way of understanding behaviour is to consider the goal hierarchy. Carver and Scheier (2001) argued that any specific behaviour is more likely to be enacted when it serves multiple higher order goals (Figure 4.2). Thus, behaviour B is more likely to be enacted than behaviour A, because it serves higher goals. A behaviour such as eating fruits and vegetables that only serves one goal (healthy eating) is less likely to be enacted, whereas an alternative behaviour such as walking the dog, which may serve multiple goals, for example increasing physical activity, being a responsible pet owner and managing stress, is more likely to be enacted. A second factor to consider is how well a behaviour serves its higher order goals. Thus, in Figure 4.2, behaviour B serves the middle higher goal much more effectively than the other three goals.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree