Abstract

Lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly are common findings in children. Both benign and malignant processes can produce these findings and it is important to distinguish between the two so that appropriate management can be undertaken.

Keywords

Lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, lymph node biopsy, splenic visceroptosis, splenectomy, overwhelming postsplenectomy infection (OPSI)

Lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly are common findings in children. Both benign and malignant processes can produce these findings and it is important to distinguish between the two so that appropriate management can be undertaken.

Lymphadenopathy

Enlarged lymph nodes are commonly found in children. Lymphadenopathy might be caused by proliferation of cells intrinsic to the node, such as lymphocytes, plasma cells, monocytes, or histiocytes, or by infiltration of cells extrinsic to the node, such as neutrophils and malignant cells. In most instances, lymphadenopathy represents transient, self-limited proliferative responses to local or generalized infections.

Reactive hyperplasia, defined as a polyclonal proliferation of one or more cell types, is the most frequent diagnosis found in lymph node biopsies in children.

Lymphadenopathy, however, may be a presenting sign of malignancies such as leukemia, lymphoma, or neuroblastoma. It is important to be able to differentiate benign from malignant lymphadenopathy clinically. Lymphadenopathy in the head and neck region must be differentiated from several other nonlymphatic masses due to congenital malformations ( Table 4.1 ).

|

Systematic palpation of the lymph nodes is important and should include examination of the occipital, posterior auricular, preauricular, tonsillar, submandibular, submental, upper anterior cervical, lower anterior cervical, posterior upper and lower cervical, supraclavicular, infraclavicular, axillary, epitrochlear, and popliteal lymph nodes. Many children have small palpable nodes in the cervical, axillary, and inguinal regions which are usually benign in nature.

When a child presents with lymphadenopathy, management is based on the following factors.

History

This involves the duration of the lymphadenopathy; presence of fever; recent upper respiratory tract infection; sore throat; skin lesions or abrasions, or other infections in the lymphatic region drained by the enlarged lymph nodes; immunizations; medications; previous cat scratches, rodent bites, or tick bites; arthralgia; sexual history; transfusion history; travel history; and consumption of unpasteurized milk. Significant weight loss, night sweats, or other systemic symptoms should also be recorded as part of the patient’s history.

Age

Although in young children cervical lymphadenopathy, especially in the upper cervical region, is usually due to infection, more serious disorders may have to be considered.

In children younger than 6 years, the most common cancers of the head and neck are neuroblastoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, leukemia, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. In children 7–13 years of age, non-Hodgkin lymphoma and Hodgkin lymphoma are equally common, followed by thyroid carcinoma and rhabdomyosarcoma; and for those older than 13 years Hodgkin lymphoma is the more common cancer encountered.

Location

Enlargement of tonsillar and inguinal lymph nodes is most likely secondary to localized infection; enlargement of supraclavicular and axillary lymph nodes is more likely to be of a serious nature. Enlargement of the left supraclavicular node, in particular, should suggest a malignant disease (e.g., lymphoma or rhabdomyosarcoma) arising in the abdomen and spreading via the thoracic duct to the left supraclavicular area. Enlargement of the right supraclavicular node indicates intrathoracic lesions because this node drains the superior areas of the lungs and mediastinum. Palpable supraclavicular nodes are an indication for a thorough search for intrathoracic or intraabdominal pathology.

Localized or Generalized

Lymphadenopathy is either localized (one region affected) or generalized (two or more noncontiguous lymph node regions involved). Although localized lymphadenopathy is generally due to local infection in the region drained by the particular lymph nodes, it may also be due to malignant disease, such as Hodgkin lymphoma or neuroblastoma. Generalized lymphadenopathy is caused by many disease processes. Lymphadenopathy may initially be localized and subsequently become generalized.

Size

Nodes in excess of 2.5 cm should be regarded as pathologic. In addition, nodes that increase in size over time are significant.

Character

Malignant nodes are generally firm and rubbery. They are usually not tender or erythematous. Occasionally, a rapidly growing malignant node may be tender. Nodes due to infection or inflammation are generally warm, tender, and fluctuant. If infection is considered to be the cause of the adenopathy, it is reasonable to give a 2-week trial of antibiotics. If there is no reduction in the size of the lymph node within this period, careful observation of the lymph node is necessary. If the size, location, and character of the node suggest malignant disease, the node should be biopsied.

Diagnosis of Lymphadenopathy

Table 4.2 outlines the differential diagnosis of lymphadenopathy.

|

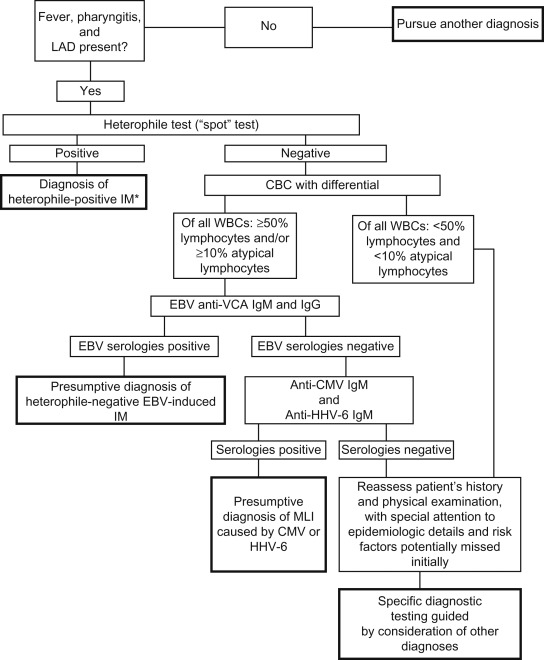

Figure 4.1 provides a diagnostic algorithm for evaluation of mononucleosis-like illness and Figure 4.2 for diagnostic evaluation of cervical lymphadenitis.