Total mesorectal excision (TME) remains the gold standard in the treatment of patients with early-stage rectal cancer. The reported oncological outcomes of this approach for stage I disease are excellent, with local recurrence (LR) rates of 3%, and 5-year survival as high as 93%.1 But TME is a major operation associated with some mortality and significant morbidity. More than one in three patients develop perioperative complications.2 Anastomotic leak with low rectal anastomosis occurs in approximately 10% of patients, and has been associated with poor oncological outcomes.3,4 Injuries to the hypogastric and pelvic nerves can cause genitourinary dysfunction in up to 40% of patients5; functional disturbances such as tenesmus, bowel urgency, soiling, and fecal incontinence are also common.6 To prevent the consequences of anastomotic leak, many patients are given a temporary diverting loop ileostomy, which is inconvenient and adds to the burden of morbidity.7 In addition, between 20% and 30% of all rectal cancers—and a higher proportion of patients with distal rectal cancers—require an abdominoperineal excision (APE) of the rectum with a permanent colostomy, a procedure that significantly impacts patients’ quality of life.5

The first transanal excision of rectal cancer is attributed to Lisfranc in 1827.8 In 1884, Kraske described a posterior approach involving resection of the coccyx and partial sacrectomy.9 (This technique never gained popularity in the United States.) In the 1960s, York-Mason introduced the transsphincteric approach10 (originally described for tumors in the anterior rectal wall, this procedure is still the preferred technique for rectourethral fistulae repair in some specialty centers). It was Parks who introduced transanal excision (TAE) in the 1960s. Using a special set of speculums still utilized by many surgeons, TAE was performed without dividing the anal sphincter.11 In the 1980s, a novel platform known as transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) was introduced by Buess.12 Since then two additional platforms—transanal endoscopic operation (TEO) and transanal minimally invasive surgery (TAMIS) have been developed. In these platforms, the rectum is distended by insufflation with CO2, and tumor resection proceeds under direct endoscopic visualization with specially designed or conventional laparoscopic instruments. In addition to providing enhanced visualization and superior instrumentation, a significant advantage of these transanal endoscopic approaches (TEM, TEO, TAMIS) is the possibility of reaching tumors located in the mid and upper rectum, beyond the limits of conventional TAE.

The advantages of local excision (LE) compared to radical surgery (RS) are many: shorter operative time, minimal fluid requirement, minor blood loss, shorter hospital stay, and a quicker postoperative recovery. Morbidity and mortality rates are significantly lower after LE compared to RS, but LE is associated with a higher risk of LR, particularly in the setting of T2N0 tumors. Many patients who develop a LR after LE can undergo salvage RS, but their probability of survival is lower compared to patients treated initially with RS. Prospective data comparing long-term survival in patients with early-stage rectal cancer treated with LE versus RS is limited. Available data from retrospective case series suggest that overall survival (OS) may not be significantly different for carefully selected T1 tumors; but, in comparison to RS, LE is clearly an inferior treatment.

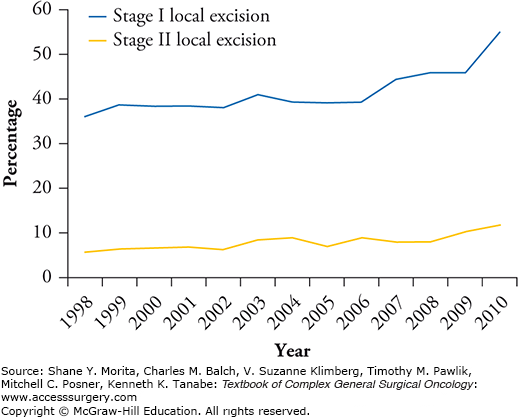

In spite of these disappointing results, the use of local treatment for early-stage rectal cancer is increasing. A recent review of the National Cancer Database found that LE procedures for T1 tumors increased from 39.8% in 1998 to 62% in 2010, and from 12.2% to 21.4% for T2 tumors (Fig. 109-1).13 In this chapter, we discuss the indications for LE, the patient selection process, surgical techniques, and outcomes of LE in the treatment of early-stage rectal cancer.

FIGURE 109-1:

Trends of LE use in the United States (1998–2010). Trends showing an increase in the use of local excision for early-stage rectal cancer in the United States between 1998 and 2010. (Reproduced with permissiom from Stitzenberg KB, Sanoff HK, Penn DC, et al. Practice patterns and long-term survival of early-stage rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. December 1, 2013;31(34):4276–4282.)

The only rectal tumors that are potentially curable by LE are those that have not penetrated beyond the bowel wall or metastasized to the regional lymph nodes. The main challenge is the reliable identification of patients amenable to LE. When stratified by stage, tumor size is not an absolute contraindication for LE, but larger tumors do harbor a greater risk of extramural spread and lymph node metastasis. Additionally, defects in the rectal wall may portend a greater chance of postoperative stricture. Ulcerated tumors tend to be locally advanced, but tumor morphology is not an absolute contraindication for LE either.

Only tumors located within 6 to 8 cm of the anal verge (AV) are amenable to conventional TAE, and modern surgical techniques and instrumentation make it easy to reach tumors in the upper rectum. Some histological tumor characteristics such as high grade, lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion, or tumor budding are associated with a high risk of nodal and distant metastasis contraindicate LE. However, these unfavorable histological features are not always detectable in a small endoscopic biopsy sample, and may be identified only after a full-thickness LE.

The characteristics of the ideal candidate for LE are listed in Table 109-1.

Characteristics of Ideal Candidate for Local Excision35

| <30% bowel circumference |

| <3 cm in size |

| Margin clear (>3 mm) |

| Mobile, nonfixed lesions |

| Within 8 cm of anal verge |

| T1 only |

| Endoscopically removed polyp with cancer or indeterminate pathology |

| No lymphovascular invasion or perineural invasion |

| Well to moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma |

| No evidence of lymphadenopathy on pretreatment imaging |

Patients diagnosed with rectal cancer should be evaluated with complete medical history, physical examination, and baseline carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA). Digital rectal exam (DRE) is important in determining tumor characteristics such as consistency, size, location, and distance from the AV. Tumor mobility in relation to the bowel wall provides indirect but valuable information about the depth of tumor invasion. Tumor that invades only the submucosa can be easily displaced with the examining finger, while tumor invading the muscularis propria tends to move with the bowel wall on DRE. Deeper tumors are tethered or fixed. However, the accuracy of DRE in assessing depth of tumor invasion and the presence of nodal metastasis is limited, and is dependent on the expertise of the examining practitioner. In addition, DRE is only valuable in the setting of very distal tumors. Therefore, accurate preoperative staging of early-stage rectal cancer cannot rely exclusively on DRE.

A rigid proctoscopy is the best way to measure the distance of tumor from the AV (the lower end of the surgical anal canal). Placing the tip of the instrument at the lower part of the tumor, the first mark seen in the scope provides the most accurate assessment of its distance from the AV. A complete colonoscopy should also be performed in every patient, as 5% of patients may have a second primary. .

Local staging is done with endorectal ultrasound (ERUS) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). ERUS is probably the most valuable tool in the staging of early rectal tumors. As an imaging modality it provides high-resolution images of the different layers of the bowel wall. It also provides valuable information about the status of mesorectal lymph nodes located close to the bowel wall. The evidence in the literature suggests that ERUS is more accurate in distinguishing between benign villous adenomas and invasive cancers, and accurately distinguishes tumors limited to the bowel wall from those invading the mesorectum. However, its accuracy in distinguishing T1 from T2 tumors is limited. In a large meta-analysis of 90 publications, the sensitivity of ERUS in identifying tumor invasion beyond the bowel wall was reportedly 91%, whereas specificity was 79%.14 In some series the ability to distinguish a T1 tumor from a T2 is only 50%, with an equal number of tumors over- and understaged. The sensitivity of ERUS in identifying nodal metastasis ranges from 64% to 75%.

MRI with endorectal coil can also delineate the layers of the bowel wall. However, it is more expensive, less convenient, and no more accurate than ERUS. Therefore, endorectal coil MRI has not gained wide acceptance. However, phased-array MRI has become the gold standard in preoperative staging of rectal cancer, providing high-resolution images of the rectal wall, mesorectum, surrounding pelvic structures, and pelvic floor muscles. MRI is especially useful in staging advanced tumors, specifically defining the depth of invasion into the mesorectum, nodal status, and the relationship of the tumor within the mesorectal fascia. While MRI is not more accurate than ERUS in identifying tumor extension through the bowel wall, it is probably more accurate in identifying nodal metastasis. Phased-array MRI does not depict the layers of the bowel wall, and therefore cannot reliably distinguish a T1 from a T2 tumor, but it facilitates the staging of early-stage rectal cancer by identifying tumors that have penetrated beyond the bowel wall or metastasized to the mesorectal lymph nodes, thereby identifying patients who are not candidates for LE. During preoperative staging, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis should also be performed to identify those few patients with apparently early-stage tumors who may have metastatic disease.

Baseline function is another important consideration in presurgical planning. A main advantage of LE over RS is the possibility of organ and functional preservation; therefore, patients with baseline fecal incontinence are less likely to benefit from LE. Bowel function should be evaluated and taken into consideration when choosing between LE and RS.

Patients must be nil per os (NPO) and undergo full bowel preparation, which facilitates visualization during the operation. While not strictly necessary, mechanical oral bowel preparation is recommended prior to LE to ensure an empty rectum and a colon free of fecal matter, in case of unexpected entry into the peritoneal cavity. As in other colorectal procedures, perioperative prophylaxis with broad-spectrum antibiotics covering gram-negatives and anaerobes should be given. For very low rectal tumors (<2 cm from the AV) extended prophylaxis for 5 days is recommended, based on retrospective data showing a higher rate of pelvic sepsis in these cases.15

Thromboprophylaxis is performed with sequential compression devices and unfractionated or low-weight heparin. These patients are at increased risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE). Because of the cancer diagnosis, pelvic procedures in colorectal surgery also carry an increased risk; however, it is not clear if this data is generalizable to transanal procedures.

Either general or regional anesthesia is acceptable in TAE; but TEM/TEO/TAMIS procedures are best performed under general anesthesia, with muscle relaxant or pudendal nerve block. Urinary catheterization is indicated for bladder decompression.

The positioning of the patient on the operating table is chosen based on tumor location; it is always advisable to perform the resection with the lesion in the inferior aspect of the surgical field. Tumors in the anterior wall are better exposed with the patient in the prone jack-knife position (Fig. 109-2), whereas posterior tumors are better visualized with the patient in lithotomy. The operating table should be in slight Trendelenburg position, and care must be taken to adequately pad the patient at weight-bearing points. The buttocks are usually taped apart and a Lone Star retractor (Lone Star Medical Products Inc., Stafford, TX) is used to efface the anus and expose the distal rectum. A headlamp is invaluable in illuminating the narrow surgical space. Instruments used include Pratt’s bivalve speculum, and Hill–Ferguson and Ferguson–Moon rectal retractors. For more proximal tumors, the Deaver and short Wylie retractors are especially helpful.

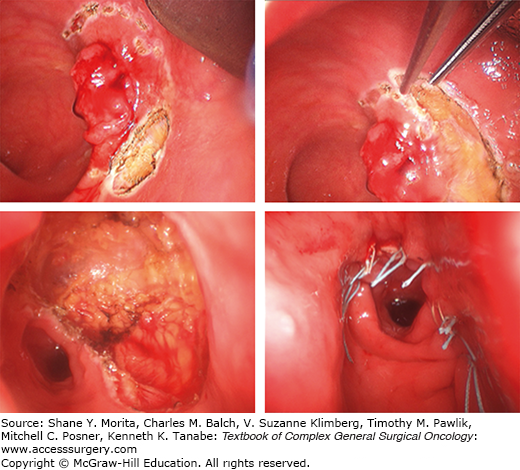

Surgery begins by marking the rectal wall with electrocautery 1 cm outside the visible margin of the lesion in all directions. Traction sutures can be placed in the normal adjacent tissue to provide better exposure, retraction, and mobilization of the specimen. Resection is undertaken with electrocautery, beginning proximally and moving distally. The objective is to obtain a full-thickness specimen; therefore, dissection should extend into the surrounding mesorectal tissue. The specimen is then undercut through the perirectal fat. Some surgeons advocate obtaining a conical margin of mesorectum with the intention of sampling the mesorectal lymph nodes. Special care must be taken in deeper anterior excisions to avoid injuring the vagina in females and the prostate or urethra in males. Once resected, the wound is abundantly irrigated and hemostasis is performed if necessary. Closure of the defect is routinely achieved in a transverse fashion with 3-0 absorbable interrupted sutures (Fig. 109-3). Patency of the rectum is controlled with proctoscopy at the end of the procedure.

The TEM platform (Richard Wolf Medical Instruments Corp., Vernon Hills, IL) consists of a number of large operating beveled or flat-end proctoscopes (4 cm in diameter), with a CO2 insufflation system, and binocular optics that provide three-dimensional visualization. Specially designed angles in the tip instruments (graspers, electrocautery) are used to perform the resection. Recently, a simplified transanal endoscopic operating system (TEO) that utilizes conventional laparoscopy insufflator, camera, and instrumentation was developed by the Karl Storz Corporation (El Segundo, CA). The TEO is less sophisticated but much more affordable than the TEM platform.

As in TAE, patients are positioned based on tumor location to ensure that the tumor is positioned inferiorly in the surgeon’s field of view. As the operating table may be moved sideways or in Trendelenburg for optimal visualization throughout the procedure, it is important to secure the patient to the table.

After patient positioning, the TEM/TEO platform is mounted onto the table with a supporting arm, and, after dilatation, the proctoscope is inserted into the anus (Fig. 109-4). Pneumorectum is established with pressure between 15 and 26 mm Hg; full-thickness excision is performed through the proctoscope using the specialized TEM or conventional laparoscopic instruments, following the principles described for TAE. After resection and profuse irrigation of the resection wound, the rectal wall defect is closed with a continuous running suture of 3-0 absorbable material. The defects in the extraperitoneal portion of the rectum may be left open to prevent abscess and dehiscence in cases where suture would be subjected to great tension. In mid and upper rectal tumors, entrance into the peritoneal cavity is often recognized by a sudden loss of pressure in the pneumorectum and the development of pneumoperitoneum. In this event the peritoneal defect must be closed, and rectal wall closure must be attempted. It is a good idea to extend antibiotic prophylaxis in these cases. The placement of a small laparoscopic trocar in the abdominal cavity may be necessary in order to evacuate the pneumoperitoneum. Special attention should be taken with respect to hemostasis, since PO bleeding is a frequent complication. Once the case has been concluded, the rectum is irrigated, checked for patency, and packed.

Of note, these platforms might not be suitable in the setting of very low rectal tumors; mounting the platform is somewhat difficult in these cases, and a good seal for the pneumorectum is difficult to achieve. In this setting TAE may be the preferred option. On the other hand, distal tumors located more than 6 cm from the AV are easily reachable, and might be the ideal indication for using these new technologies.

The most recent innovation in transanal excision is Transanal Minimally Invasive Surgery (TAMIS). Introduced in 2010, TAMIS involves the use of a laparoscopic single port platform (SILS™ Port, Covidien, Bolder, CO) or the Gel Point Path System™ (Applied Medical, Santa Margarita, CA) along with conventional laparoscopic insufflation, optics, and instrumentation. The resection is performed in a similar fashion to TEM/TEO, using standard laparoscopic instruments. TAMIS has the advantage of lower cost compared with the two previously described platforms. However, for obese patients with a long anal canal, TAMIS may not be indicated; this is because the short length of the platform may be insufficient for transversing the sphincteric complex. In resection of tumors located outside the inferior aspect of the field, the use of a nonfixed camera, particularly one with a flexible tip, could enable a more flexible initial positioning of the patient. On the other hand, a mobile camera requires an assistant and entails the risk of collision with the operating instruments. TAMIS platforms have been used in combination with robotic surgery, but the results are still preliminary.

After LE, surgical specimens should be pinned down with orientation marks before being sent for pathological examination (Fig. 109-5). The pathologist will ink each margin with different colors (superior, inferior, right lateral, left lateral, and deep) to rule out margin involvement. Standard pathological evaluation should include margin status, T stage and—in the setting of T1 tumors—depth of submucosal invasion, differentiation, budding, lymphocytic infiltration, perineural invasion, lymphovascular invasion, tumor grade, and differentiation. If the patient has been treated with neoadjuvant radiation or chemoradiation, tumor regression grade should also be included. Final pathologic examination is the ultimate determinant of LE sufficiency, or indication for TME.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree