31 Intraventricular Tumors

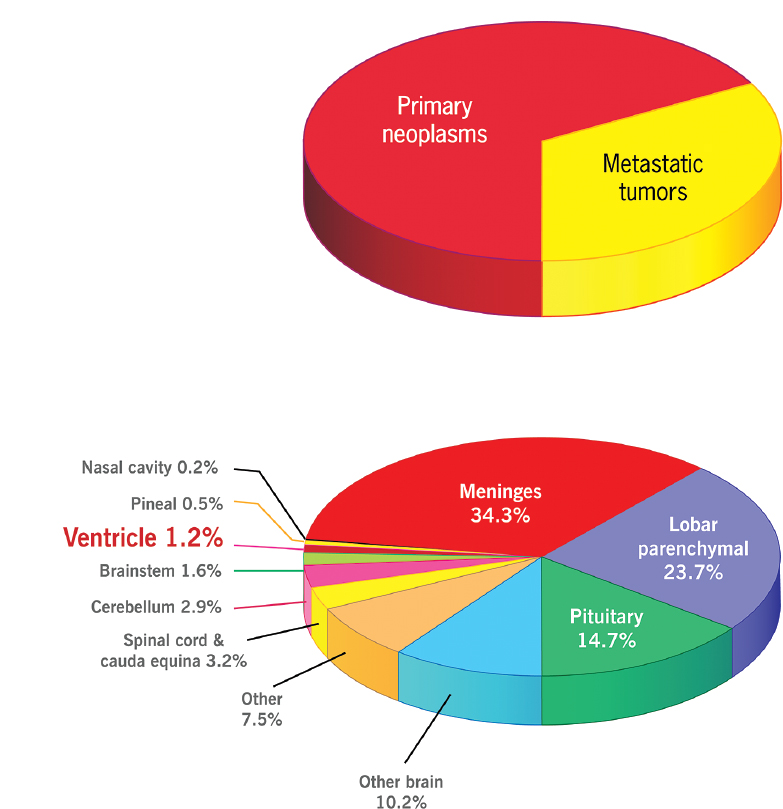

Intraventricular (IV) tumors are a relatively rare subset of all intracranial tumors1 (Fig. 31.1). They represent a diverse group of histopathologies spanning from low-grade or benign lesions to highly malignant primary or metastatic lesions. These lesions are located within the fluid-filled spaces of the ventricular system. As such, they represent a challenging group of tumors to treat, not only because of the wide variety of pathologies but also because they are deep-seated lesions and they are in close proximity to a variety of critical neurologic and vascular structures, leading to the potential for significant morbidity as a side effect of treatment. Tumors are considered primarily IV if they arise completely within the ventricular system or secondarily IV due to exophytic growth of a parenchymal tumor directly adjacent to the ventricular system. This chapter provides a general overview of the types and distribution of IV tumors, describes commonly used surgical approaches to these tumors, and offers representative examples.

Special Consideration

• Intraventricular tumors are deep-seated lesions whose morbidity and potential mortality arise due to their close anatomic proximity to important neurovascular structures such as the genu of the internal capsule, the internal cerebral veins, and the thalamic perforators. This is due to the structures that must be sacrificed or transgressed to reach the lesions such as cortical bridging veins, the functional cortex, and deep white matter tracts.

Epidemiology

Epidemiology

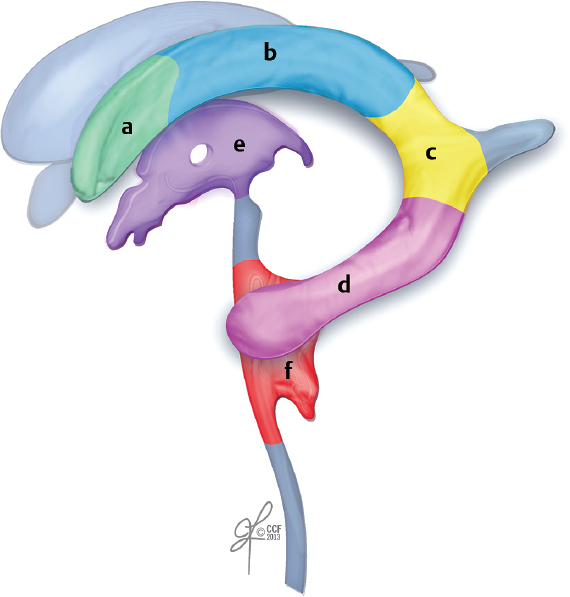

The differential diagnosis for any given IV tumor depends on its location, patient characteristics (e.g., age), and the radio-graphic characteristics of the lesion on multiple imaging platforms [typically magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), but potentially computed tomography (CT) and angiography]2,3 (Fig. 31.2 and Table 31.1). A simple list of the potential pathologies to be considered for any intraventricular lesion includes at least choroid plexus papilloma (CPP), choroid plexus carcinoma, ependymoma, anaplastic ependymoma, subependymoma, meningioma, subependymal giant cell astrocytoma (SEGA), central neurocytoma, oligodendroglioma, glioblastoma, and metastasis.2–5 Beyond this already lengthy list of primarily solid tumors, there are other diagnostic possibilities including cysts (e.g., colloid and ependymal cysts); other less common tumors, including perineurinomas, hemangiopericytomas, and solitary fibrous tumors; and potentially even some inflammatory or infectious lesions, such as neurocysticercosis.2,4

Pearl

• Using a combination of tumor location in the ventricular system, imaging characteristics of the tumor, specific patient demographics, and history can often help to significantly narrow the differential diagnosis for a given IV tumor.

Some diagnostic possibilities can be narrowed down based on patient demographics and the location of the tumor. For example, CPP in childhood is more likely to be within the lateral ventricles, whereas CPP in adulthood is most commonly seen in the fourth ventricle.4 Some tumors may be seen preferentially in patients who have specific tumor syndromes, such as subependymal giant cell astrocytoma in tuberous sclerosis or intraventricular meningioma in neurofibromatosis.3–5 Finally, for IV metastases, many different primary pathologies have been reported: renal, pulmonary, breast, colon, gastric, bladder, lymphoma, thyroid, and melanoma; however, although breast and lung cancer are by far the most common systemic cancers to produce intracranial metastases, the risk of having a CNS metastasis in an intraventricular location may be highest in renal cell carcinoma.6

Intraventricular tumors are also varied with regard to their histological and imaging properties. Some tumors show well-differentiated histological patterns including the papillary structures with fibrovascular cords seen in CPP or the perivascular pseudorosettes that can be seen in well-differentiated ependymoma. Calcification may be found in many types of IV tumors including meningioma, CPP, ependymoma, subependymoma, central neurocytoma, and SEGA, and as a result may not by itself be as useful for narrowing the differential diagnosis. On imaging, some of these tumors may show relatively uniform enhancement, such as meningioma and CPP, or no enhancement in central neurocytoma, whereas others have more heterogeneous imaging characteristics, such as nonuniform enhancement in ependymoma, subependymoma, and atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor, or heterogeneous intrinsic T1 or T2 signal from hemorrhage or areas of necrosis in higher grade ependymoma or glioblastoma.2,3,5 Finally, some IV tumors appear to be well demarcated from the surrounding structures, such as subependymoma (often attached to the ventricular wall via a stalk) or meningioma, as well as metastases, which tend to be attached to the choroid plexus, in contrast to other tumors that are growing into the ventricle as an exophytic component of an intraparenchymal tumor, such as glioblastoma or brainstem glioma.

Special Consideration

• Many IV lesions have either low-grade or benign histologies. Enthusiasm for resection must be appropriately balanced with the potential for complications in order to tailor treatment and maximize the outcome for each patient.

Clinical Presentation

Clinical Presentation

Patients with IV tumors seem to preferentially present with signs or symptoms of increased intracranial pressure (ICP) as opposed to clear focal neurologic deficits. Several authors have documented the presenting symptoms in their specific case series,7,8 with the more common presenting symptoms of an IV tumor being nonlocalizing neurologic problems such as headache, nausea and vomiting, visual disturbance, gait problems, and memory difficulties.7–10 Also, acute obstruction from a third or fourth ventricular tumor or cyst may result in spastic paraparesis and altered level of consciousness, including coma. This is in contrast to the focal deficits like focal motor or sensory deficit, aphasia, or agnosia that may more commonly be seen in patients with parenchymal tumors or cranial nerve deficits that may be seen in skull base tumors. Although potentially less common with IV tumors, seizures can still be a part of the constellation of presenting symptoms with a reported incidence of 5.6% in a series of IV metastases.11

Surgical Management

Surgical Management

The surgical treatment of IV tumors can be categorized based on the approach used. The modern neurosurgical literature describes in detail the traditional open approaches to IV tumors7,8,10,12–14 and the more recent endoscopic approaches for some of the same lesions.15,16 Chapter 13 discusses endoscopic treatment approaches, so those approaches to IV tumors are not discussed here.

The surgical approach for any particular tumor is largely determined by its location (e.g., temporal horn versus adjacent to the foramen of Monro), the surrounding neurovascular anatomy, the proposed differential diagnosis, and the overall goals of the surgery. The goals for surgery are similar to those for any other cranial tumors. These include the specific goals of obtaining a histological diagnosis and debulking or completely resecting the lesion, typically described as maximal safe resection, to relieve mass effect. An additional goal that may be present for IV or periventricular tumors is that of reestablishing patency of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pathways. Given that many IV tumors present with hydrocephalus and signs and symptoms of increased ICP, often one of the main goals is to reestablish normal CSF flow and to relieve the “mass effect” caused by excess CSF trapped within the ventricular system “upstream” of the tumor.

General Surgical Principles

General Surgical Principles

Each patient should provide a full history and be given a physical examination not only to describe and document their neurologic disabilities but also to evaluate and compensate for any systemic derangements that may affect perisurgical and intraoperative care, such as diabetes, heart disease, and chronic steroid dependence. Once the decision has been made to pursue surgical intervention, preoperative planning includes selection of appropriate antibiotic and thromboembolism prophylaxis as well as imaging to define the lesion and for neuronavigation. Other important perioperative considerations include potential CSF diversion with external ventricular drainage and preoperative estimation of the potential for blood loss so that appropriate provisions are available for blood loss/volume replacement as needed. Finally, careful consideration needs to be given to the proposed positioning for surgery to protect the patient during a potentially long period of immobility, to maximize exposure of the lesion, and to reduce surgeon fatigue during the course of the operation.

Table 31.1 Representative Intraventricular Tumors Arranged by Location Within the Ventricular System

| Frontal Horn | Anterior Third | Fourth Ventricle |

| Astrocytoma | Colloid cyst | Ependymoma |

| Oligodendroglioma | Subependymoma | Subependymoma |

| Central neurocytoma | Gliomas | Medulloblastoma |

| Subependymoma | Craniopharyngioma | Choroid plexus papilloma |

| Metastasis | Central neurocytoma | |

| Atrium | Posterior Third | Temporal Horn |

| Meningioma | Astrocytoma | Metastasis |

| Metastasis | Pineal tumor | Meningioma |

| Choroid plexus papilloma | Metastasis |

• Potential neurologic complications from surgical resection of IV tumors include hemorrhage, hydrocephalus, visual disturbance, language disorder, cognitive impairment, arterial or venous infarction, infection, hypothalamic injury, endocrine disturbance, and seizure.

Important general postoperative considerations include (1) duration of anticonvulsant therapy, if used, and antibiotics; (2) prevention of common postoperative complications, including infection, via meticulous wound and ventriculostomy care, and thromboembolism, via early mobilization; and (3) early imaging or laboratory evaluation if there are concerns about the potential for retained tumor, continued hydrocephalus. or other complications.

Surgical Approaches to Intraventricular Tumors

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree