39 Intradural Spinal Tumors

Spinal tumors encompass a range of histologies that reflect the diversity of cell types within the spinal cord and nerve roots as well as supporting structures inside the thecal sac. They most frequently present with pain, often in the absence of discrete neurologic findings early in the course of the illness. Most spinal cord tumors are best treated and often cured with complete surgical resection. Because functional outcomes after surgery are closely linked to the preoperative neurologic condition, systematic inclusion of spinal cord tumors in the differential diagnosis for back or limb pain can result in a timely diagnosis that can profoundly impact patient outcomes. Adjuvant radiation has a variable role for malignant tumors depending on histology, and remains the subject of some controversy. Radiosurgery for the spine is now widely available, but its role in the management of these heterogeneous, predominantly benign neoplasms is still being assessed.

Histology and Epidemiology

Histology and Epidemiology

Although there is significant crossover, intradural spinal tumors are divided into two main anatomic categories: intramedullary and extramedullary. Intramedullary tumors arise within spinal cord parenchyma and are primarily of glial origin (astrocytomas, ependymomas, gangliogliomas) or vascular origin (hemangioblastomas). Extramedullary tumors grow within the subarachnoid space and arise mostly from cells within the nerve roots (neurofibromas, schwannomas) or the meninges (meningiomas). Other, rarer tumors stem from ectopic tissues found in association with these structures. Some of these are a result of embryological errors (dermoids, epidermoids, teratomas, lipomas) and others a result of systemic malignancy (intramedullary or extramedullary intradural spinal cord metastases).

Intramedullary tumors occur throughout the spinal cord. Age of presentation is bimodal, with the first peak occurring in children 5 to 10 years of age and the second occurring in adults in their mid-30s. To a degree, the patient’s age can anticipate the histology of spinal cord tumors. Ependymomas are the most common intramedullary lesions in adults,1 whereas in children, astrocytomas are much more prevalent.2 In adults, 35 to 40 years as a mean age of presentation is remarkably constant over series of patients with the three most common adult intramedullary tumors: ependymomas,3,4 astrocytomas,5 and hemangioblastomas.6 High-grade astrocytomas have been found most commonly in adolescents.7 Adult extramedullary lesions tend to present later in life, with large series showing peak ages of presentation between 45 and 50 years of age for schwannomas8 and between 50 and 65 years of age for meningiomas.9,10 The incidence of lesions resulting from embryological errors increases significantly with decreasing age, reaching 31% of spinal tumors in children under 15 years of age11 and 65% of spinal tumors in children under 1 year of age.12

Clinical Presentation

Clinical Presentation

Although patients can present with a range of symptoms, the most common complaint in adults with spinal tumors is pain.3 The development of motor deficits, in particular gait disturbances, may ultimately be the symptom most likely to attract medical attention in young children because of their inability to verbalize effectively complaints of pain. The pain generated by an intramedullary tumor is typically axial, dull, and aching; of gradual onset; and not easily explained by pathological changes to known sensory pathways. Because this symptom is somewhat vague and is often not associated with any neurologic deficit early on, the lapse between symptom onset and diagnosis is often prolonged. Pain from extra-medullary lesions may be radicular, mimicking a herniated disk, or axial depending on histology and cord involvement. Sensory changes, including paresthesias and sensory loss, are approximately as common as weakness as a second presenting symptom.

Pitfall

• The classic syndrome of an intramedullary tumor is a central, dull, aching pain of gradual onset, not easily explained by pathological changes to known sensory pathways. Because this symptom is somewhat vague and is often not associated with any neurologic deficit early in the course of the illness, the lapse between symptom onset and diagnosis is often prolonged.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

The signs and symptoms of spinal tumors can resemble many other disorders affecting the spinal axis, including musculoskeletal pain syndromes (fibromyalgia), autoimmune disorders (transverse myelitis, multiple sclerosis), degenerative disease (ruptured intervertebral disks, spinal stenosis, synovial cysts), vascular lesions (cavernous malformations, arteriovenous malformations), infectious processes (epidural abscess, viral radiculitis, syphilis), traumatic lesions (syringomyelia, chronic dens fracture), congenital malformations of the spine and skull base (Klippel-Feil), motor neuron disease (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [ALS]), and other miscellaneous disorders (arachnoiditis, hypertrophic arthritis, B12 deficiency). Information gathered from a careful medical history and a detailed neurologic examination can help to navigate through this extensive differential diagnosis. For example, a relapsing, remitting course compared with a slow, steady decline is much more typical of multiple sclerosis than of a spinal tumor. A patient with motor findings in the absence of any sensory disturbances hints at a motor neuron disease. As a practical matter, however, there are two critical branch points in the clinician’s decision analysis: (1) when to order spinal imaging; and (2) how to distinguish between spinal tumors and other, nonoperative lesions that can resemble them on imaging studies.

As a general rule, any patient with a new neurologic complaint localizing to the spine requires spinal imaging. The same applies to patients whose pain falls in a radicular pattern. Patients with vague complaints of back pain in the absence of neurologic symptoms may present a bit of a dilemma; however, a patient with gradual onset of constant, dull midback pain over weeks to months should pique enough suspicion to merit an imaging study.

Imaging Studies

Imaging Studies

When imaging is deemed appropriate, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the modality of choice. Often, a noncontrast MRI specific to the spinal level to which signs and symptoms localize is the initial study to detect a lesion. If such a study is suggestive of a spinal tumor or of an associated abnormality such as a syrinx, a full spinal axis gadolinium-enhanced MRI is indicated. Lesions that can resemble spinal cord tumors on MRI include inflammatory processes, such as transverse myelitis, multiple sclerosis, and sarcoidosis; degenerative processes, such as synovial cysts; and traumatic lesions, such as cord edema and syringes. Spinal tumors enhance with contrast in a fashion that is specific enough to remove ambiguity in most cases; however, the enhancing tumor may be sufficiently remote from the sentinel lesion discovered on initial imaging studies that it can be missed if the entire spinal axis is not imaged. Spinal cord tumors can also be distinguished from other nonneoplastic lesions because they produce a redundancy of tissue that dramatically enlarges cord diameter.

Pitfall

• Any syrinx needs contrast-enhanced imaging of the entire spine.

Pearl

• Spinal cord tumors can usually be distinguished from inflammatory lesions because they are more likely to be enhancing and they expand the cord significantly.

When imaging studies are consistent with a spinal tumor, additional specialized MRI modalities can point to specific diagnoses. Nonenhancing congenital lesions with high lipid content are suggested when fat-suppressed MRI sequences decrease signal intensity in all or part of the lesion. Gradient echo is useful in identifying blood products or finding tiny hemorrhagic lesions that cannot be resolved by conventional MRI modalities. Although MRI is usually sufficient to identify the relative positions of key vascular structures, such as the vertebral artery, to tumor, an angiogram is sometimes useful and will also provide the surgeon with a blueprint of a tumor’s blood supply.

Treatment

Treatment

Surgery: Operative Planning and Techniques

Most intramedullary glial tumors (e.g., ependymomas, astrocytomas) are approached via a midline incision and a joint- sparing laminectomy that extends about one level above and below the tumor. Intramedullary tumors are usually accessed through a midline myelotomy; however, a myelotomy through the dorsal root entry zone can be used for tumors lateral in the cord or if the cord is rotated. In either case, the myelotomy should be extended just beyond the rostral and caudal poles of the tumor if more than a biopsy is anticipated.

Establishment of a plane between tumor and cord parenchyma is the paramount early goal because the ability to maintain and develop this plane will dictate the aggressiveness and safety of resection. An intraoperative pathological consultation should be obtained early in the procedure and may inform the operative process; however, frozen sections are not reliable enough to distinguish between tumors for which aggressive surgical resection is indicated and tumors for which surgical goals are more limited. In practice, as long as a clear plane exists between tumor and spinal cord, gross total resection should remain the operative objective. When possible, the tumor should be removed en bloc, although this is often not practical for larger tumors for which an en bloc technique can obscure visualization of the dissection plane of the anterior portion of the tumor. Intraoperative monitoring is advocated by most surgeons, and may provide useful information regarding spinal cord function. More recently, anterior approaches have been utilized to access ventrally situated intramedullary tumors.13,14

• Intraoperative decisions concerning extent of resection of an intramedullary lesion should be based on the ability of the surgeon to develop clear surgical planes rather than on intraoperative, histopathological consultation.

Intradural extramedullary tumors are usually encapsulated and noninvasive. The goal of surgery is almost always gross total resection. A posterior midline approach is sufficient for the vast majority of tumors, even those with anterior extension. The lateral extracavitary approach or a costotransversectomy may be useful for small ventrally located tumors. Some authors have advocated anterolateral approaches for dumbbell lesions with anterior extradural extension, and good results have been achieved in experienced hands; however, these approaches have the disadvantage of leaving decompression of neural elements until the final stages of the tumor resection. In recent years, ventral and minimally invasive techniques have been described for ventrally located extra-medullary tumors.14,15

Following laminectomy, the first priority is decompression of the spinal cord. For tumors with both intradural and extra-dural components, this may require durotomy and intradural resection as a first step if the tumor is located anteriorly or anterolaterally, or extradural debulking to permit sufficient exposure to the intradural portion of the tumor if the tumor is located posteriorly. Once the tumor is exposed, cauterization of tumor capsule both shrinks and devascularizes the mass. Small tumors can be carefully dissected from neural elements and rolled away from the cord as the dissection plane develops. Large tumors often require internal debulking with a sonic aspirator. For nerve sheath tumors it is usually impossible to save the affected nerve root; however, one should always stimulate it to confirm nonfunctionality prior to cauterization and ligation. For meningiomas, excision of part of the dura mater is sometimes required for complete tumor removal. After tumor removal and hemostasis, the dura is closed primarily with patching of any dural defect with dural substitute.

Pearl

• Even when nerve sheath tumors arise from the ventral root, the root can be sacrificed without any lasting sequelae. The rare cases in which the tumor arises from a functional root can be identified with intraoperative stimulation.

Adjuvant Therapy

The overwhelming majority of clinical experience regarding adjuvant therapy is with conventional radiotherapy for intramedullary tumors. Although the benefits of radiotherapy remain controversial, many clinicians advocate a local cumulative dose of 5,040 cGy for low-grade ependymomas and astrocytomas with radiographic residual disease following surgery. High-grade lesions receive slightly higher doses, and disseminated disease requires complete craniospinal irradiation.16 Various chemotherapy strategies have been reported, but nothing approaching a consensus exists for any particular histology.17 Radiosurgery remains an investigational modality for most spinal tumors, although recent reports appear to support an expanding role of radiosurgery in the treatment of both benign and malignant intradural neoplasms.18,19

Controversy

• The utility of adjuvant radiation for ependymomas and astrocytomas is not well established. Some authors argue for gross total resection for both tumor types without radio-therapy; others advocate radiation even in cases of gross total resection. Most clinicians will consider radiotherapy for any glial tumor with residual after surgery.

Intradural Intramedullary Tumors

Intradural Intramedullary Tumors

Ependymomas

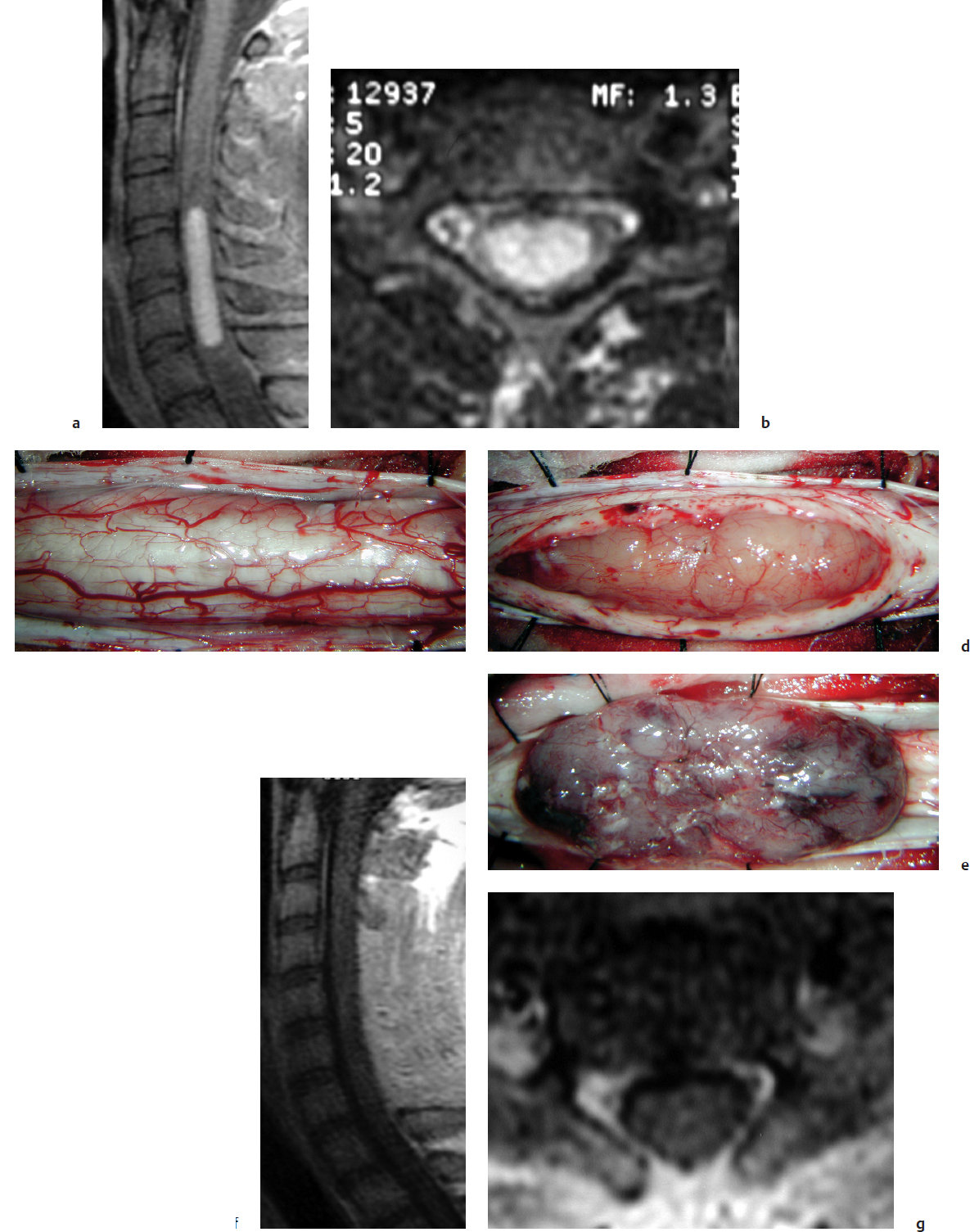

Ependymomas are usually slow-growing, benign lesions that are nonencapsulated but noninvasive. They are estimated to account for 37 to 60% of all intramedullary tumors in adults and 30% of those in children.12 They most commonly present with axial pain, roughly arising from the level of the tumor or dysesthesias that are referred to limbs or dermatomes.4,20 Sensory changes and motor deficits are common as well. Ependymomas tend to be hypointense to isointense to neural tissue on T1-weighted MRI and uniformly enhancing21 (Fig. 39.1). They can be associated with a syrinx, exhibiting polar “capping” phenomenon, or may contain intratumoral cysts. Although the typical ependymoma is centrally located within the cord, the myxopapillary subtype arises in association with the cauda equina, and subependymomas appear eccentrically within the cord. Overall, histology varies from benign subtypes, such as cellular, papillary, and myxopapillary, that carry excellent prognoses, to anaplastic varieties that may portend a more aggressive course. Metastatic spread occurs infrequently.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree