| The sarcodina (amebae) | Pathogenic Nonpathogenic | Entamoeba histolytica Entamoeba dispar Entamoeba moshkovskii Entamoeba chattoni Endolimax nana Iodamoeba butschlii Dientamoeba fragilis |

| The mastigophora (flagellates) | Pathogenic Nonpathogenic | Giardia lamblia Trichomonas hominis Chilomastix mesnili Embadomonas intestinalis Enteromonas hominis |

| The ciliophora | Balantidium coli | |

| The coccidia | Cryptosporidium parvum Isospora belli Sarcocystis species Cyclospora cayetanensis | |

| The microspora | Enterocytozoon bieneusi Encephalitozoon intestinalis | |

| Stramenopile | Blastocystis hominis |

Entamoeba histolytica

Entamoeba histolytica causes dysentery, chronic colonic amebiasis, and hepatic amebiasis. The last topic is dealt with in Chapter 204, Extraintestinal amebic infection. Amebic dysentery is a syndrome of bloody diarrhea caused by invasion of the colonic wall by trophozoites of E. histolytica. It is common in many parts of the world, especially West and southern Africa, Central America, and south Asia. In the United States, 3000 to 4000 cases are reported each year. There is now consensus that the species formerly recognized as E. histolytica in fact comprises two species: E. histolytica and Entamoeba dispar. The first is the pathogenic protozoan long associated with human invasive disease and with hepatic amebiasis, and the latter is a morphologically identical nonpathogenic protozoan first recognized as the nonpathogenic zymodeme of E. histolytica. The latter does not require treatment, but it cannot be differentiated from E. histolytica morphologically. Diagnosis of invasive amebiasis is achieved by the identification of hematophagous trophozoites in very fresh stool smears or in colonic biopsies; the latter may also show typical flask-shaped ulcerations. Serologic testing using an immunofluorescent antibody test is now an important contribution to the diagnosis of a seriously ill patient, particularly in distinguishing colonic dilation resulting from amebiasis from that caused by ulcerative colitis. Serology does not distinguish between E. histolytica and E. dispar. Diagnosis using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), which detects specific DNA sequences of genetic material, is increasingly available, and it does allow species identification.

Treatment of invasive amebiasis is shown in Table 203.2. Treatment can be divided into two stages: (1) eradication of tissue forms with metronidazole, tinidazole, or nitazoxanide and (2) eradication of luminal carriage with diloxanide furoate. Dehydroemetine and iodoquinol, used formerly for the treatment of amebiasis, are toxic and no longer used.

| Adult dosage | Child dosage | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue infection | |||

| First choice | Metronidazolea | 750 mg TID for 10 d | 50 mg/kg/d for 10 db |

| Tinidazolea | 2 g/d for 3 d | 60 mg/kg/d for 3 d | |

| Second choice | Nitazoxanide | 500 mg BID for 3 d | Age 2–3 years: 100 mg BID; age 4–11 years: 200 mg BID for 3 d |

| Paromomycin | 30 mg/kg/d for 10 db | 30 mg/kg/d for 10 db | |

| Luminal carriage | |||

| First choice | Diloxanide furoate | 500 mg TID for 10 d | 20 mg/kg/d for 10 db |

| Second choice | Paromomycin | 30 mg/kg/d for 10 db | 30 mg/kg/d for 10 db |

Intestinal amebiasis may be complicated by acute toxic colitis, presenting in a similar manner to the dilation of acute severe ulcerative colitis. The patient will be febrile and unwell, sometimes with signs of peritoneal irritation, and a plain abdominal radiograph will indicate dilation. Intravenous fluids must be given, the patient starved, and metronidazole and a third-generation cephalosporin given intravenously. Worsening dilation of the colon or perforation will necessitate surgery, but in the event of perforation, the outcome is poor. If treatment with metronidazole is started early in patients with severe amebic colitis, medical management should nearly always suffice, but surgery should not be delayed if perforation is impending.

Chronic amebiasis may be difficult to distinguish from intestinal tuberculosis or Crohn’s disease but responds to metronidazole and diloxanide as above. Surgery is sometimes necessary because stricturing may persist.

Giardia lamblia

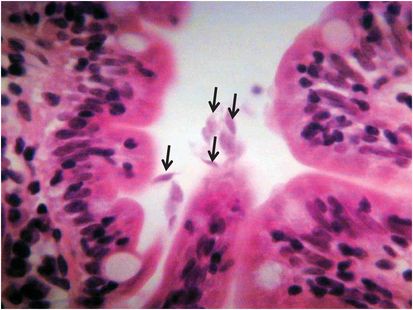

Giardia lamblia infection, first recognized by Van Leeuwenhoek in 1681, is a cause of acute and persistent diarrhea and possibly malnutrition in children in many tropical and subtropical countries. It is also a well-recognized cause of travelers’ diarrhea. In many cases it is self-limiting, but the course may be prolonged in immunoglobulin deficiencies. Asymptomatic infection is common. Diagnosis is by stool microscopy, although when this is negative and the clinical suspicion is strong, trophozoites may be detected in small intestinal fluid and mucosal biopsy specimens obtained by endoscopy (Figure 203.1). Fecal Giardia antigen enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) and PCR are now increasingly used in many routine diagnostic laboratories.

Figure 203.1 Trophozoites of Giardia lamblia in the lumen in a small intestinal biopsy (6-mm section stained with hematoxylin and eosin).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree