| Infections | Other conditions |

|---|---|

| Mycobacteria | Autoimmune |

| Tuberculosis | Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), lupus-like disease |

| Nontuberculous mycobacteria, especially Mycobacterium avium complex | Thyroid disease |

| Leprosy | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| Bacille Calmette–Guérin | Guillain–Barré syndrome |

| Fungi | Reiter’s syndrome |

| Cryptococcus | Polymyositis |

| Pneumocystis | Relapsing polychondritis |

| Histoplasma | Alopecia |

| Candida | Cerebral vasculitis |

| Trichophyton rubrum | Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura |

| Penicillium marneffei | Poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis |

| Coccidioides | Vitiligo |

| Viruses | Nephrotic syndrome |

| Herpes simplex virusa | Auto-immune hepatitis |

| Herpes zoster virusa | Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura |

| Cytomegalovirus | Other inflammatory conditions |

| JC polyomavirus | Sarcoidosis |

| Hepatitis B and C virus | Foreign-body reaction |

| Molluscum contagiosuma | Folliculitisa |

| Human papilloma virusa | Lymphoid interstitial pneumonitis |

| Polyoma BK virus | Photodermatitis |

| HIV encephalitis | Peyronie’s disease |

| Parvovirus B19 | Dermatofibromata |

| Human T lymphotropic virus type-2 | Dyshidrosis |

| Epstein–Barr virus | Gouty arthritis |

| Protozoa | Malignancy |

| Toxoplasma | Kaposi’s sarcoma |

| Microsporidia | |

| Leishmania | |

| Cryptosporidia | |

| Helminths | |

| Schistosoma | |

| Strongyloides | |

| Bacteria | |

| Bartonella | |

| Proprionibacteriaa | |

| Klebsiella | |

| Arthropods | |

| Sarcoptes scabiei |

a Common causes and manifestations of cutaneous IRIS.

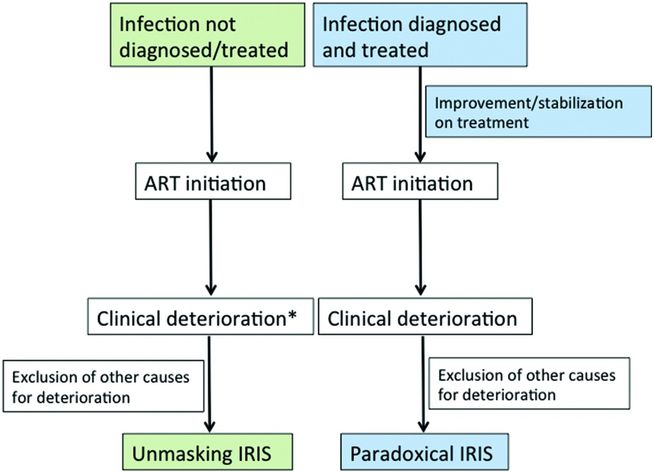

Two forms of infective IRIS are recognized: (1) paradoxical IRIS (p-IRIS), in which an OI is diagnosed and treated appropriately prior to starting ART with the subsequent development of recurrent, worsening or new symptoms and signs after starting ART and (2) unmasking IRIS (u-IRIS), in which a previously present but clinically undetected and therefore untreated OI becomes apparent after starting ART, typically with an unusually exaggerated inflammatory presentation (Figure 100.1). In both scenarios the spectrum of IRIS manifestations vary considerably; these may be localized or involve multiple organ systems and systemic inflammatory signs may be prominent. IRIS may be mild and self-limiting lasting days to weeks, or persist for years. In a small proportion of cases IRIS may be life-threatening or fatal, particularly in forms that involve the central nervous system (CNS) and those that result in airway compromise, organ failure, or organ rupture (Table 100.2). Risk factors associated with IRIS include a low CD4 count (particularly <50 cells/mm3), high HIV viral load (5 log10), high pathogen load related to the OI, a rapid decline in HIV viral load and/or rise in CD4 count on ART, and short interval between initiation of OI treatment and ART. As no confirmatory tests exist, the diagnosis of p-IRIS relies on identifying the characteristic sequence of clinical events and exclusion of other possible causes for clinical deterioration such as drug reaction or toxicity, failure of treatment for the OI (due to poor adherence, drug malabsorption or antimicrobial drug resistance), or an alternative/additional infection or malignancy. U-IRIS is diagnosed using standard diagnostic tests for the underlying infection.

Figure 100.1 Schematic representation of the typical sequence of events associated with the two forms of infective IRIS: unmasking (green) and paradoxical (blue). * = Characterized by heightened inflammatory features; ART = antiretroviral therapy.

| Causes | Manifestations |

|---|---|

| Neurologic manifestations | |

| Tuberculosis | Meningitis, intracerebral space-occupying lesions, spinal epidural abscess |

| Nontuberculous mycobacteria | Meningoencephalitis, brain abscess |

| JC virus | Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy |

| Cytomegalovirus | Encephalitis, vasculitis, ventriculitis |

| Herpes simplex virus | Encephalitis |

| Herpes zoster virus | Meningoencephalitis, vasculitis |

| Candida | Meningitis, vasculitis |

| Parvovirus B19 | Encephalitis |

| BK virus | Meningoencephalitis |

| Toxoplasma | Encephalitis |

| Auto-immune reaction | Demyelinating central nervous system disease, cerebral vasculitis, Guillain–Barré syndrome |

| HIV itself the target of IRIS | Meningoencephalitis |

| Cryptococcus | Meningitis, intracerebral space-occupying lesions, cerebellitis |

| Coccidioides | Meningitis |

| Extraneural manifestations | |

| Kaposi’s sarcoma | Pneumonitis, airway and gastrointestinal tract involvement |

| Tuberculosis | Splenic rupture, bowel perforation, airway compression by lymph nodes, pericardial effusion, and acute renal failure |

| Nontuberculous mycobacteria | Airway compression by lymph nodes, alveolitis |

| Hepatitis B and C virus | Fulminant liver failure, progression of liver cirrhosis |

| Bacille Calmette–Guérin | Disseminated disease |

| Pneumocystis | Pneumonitis |

General principles in infective IRIS prevention and management

Prior to starting ART, thorough screening for OIs and when diagnosed initiation of appropriate treatment will prevent some cases of u-IRIS. A short interval between OI treatment and ART initiation is a strong risk factor for p-IRIS. However, delaying ART comes at the cost of remaining vulnerable to HIV disease progression, additional OIs, and mortality, particularly in severely immunosuppressed patients. The optimal time for starting ART depends on the underlying OI and will be discussed in relevant sections below.

A key component of management is optimal therapy of the OI. Anti-inflammatory therapy should be considered to alleviate symptoms and reduce inflammation particularly in more severe cases. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may provide symptomatic relief in patients with mild IRIS manifestations. Corticosteroids are the most frequently used anti-inflammatory drugs, particularly in severe cases, and it is the only treatment modality for which supportive clinical trial data exist. However, corticosteroids should generally only be considered when the diagnosis of IRIS has been made with certainty, having excluded alternative causes for clinical deterioration. Corticosteroids should normally not be used in patients with Kaposi’s sarcoma and chronic hepatitis B (HBV) infection as they may worsen these conditions. There are isolated case reports of clinical response when other immunomodulatory drugs such as thalidomide and adalimumab were used to treat IRIS, but such approaches remain experimental. ART should not be interrupted in IRIS cases as this may increase vulnerability to other OIs and predispose to ART drug resistance. IRIS may also recur after ART reinitiation. ART interruption may be considered, however, as a last resort for patients with life-threatening IRIS, particularly those nonresponsive to corticosteroid therapy.

Pathogen-specific IRIS manifestations

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree