Imaging and endoscopy both play important and complementary roles in the initial diagnosis, staging, monitoring, and symptomatic management of pancreatic cancer. This article provides an overview of the uses of each of the diagnostic modalities, common imaging findings, alternative considerations, and areas of ongoing work in diagnostic imaging. This article also provides details of the uses of endoscopy for diagnosis, staging, and intervention throughout the course of a patient’s care. These modalities each play important roles in the complex multidisciplinary care of patients with pancreatic cancer.

Key points

- •

Imaging and endoscopy have complementary strengths that should be used as part of a multidisciplinary oncology care plan.

- •

Computed tomography (CT) is the primary imaging modality for routine diagnosis, staging, and monitoring of patients with cancer, but MRI and PET with fludeoxyglucose F 18 (FDG-PET) can be useful in certain problem-solving situations.

- •

Endoscopy provides accurate local and regional nodal staging via endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) and can provide immediate diagnostic tissue sampling and supportive interventions.

Introduction

Noninvasive imaging and endoscopy play important and complementary roles in the diagnosis and management of patients with pancreatic cancer. Imaging, primarily in the form of ultrasonography (US) and CT, is often the first line of investigation for the symptoms of pancreatic cancer. Imaging is widely available and can provide noninvasive diagnostic and staging information, while endoscopy offers complementary diagnostic and therapeutic tools throughout the spectrum of care. The following sections examine the roles and importance of each of these modalities for pancreatic cancer.

Introduction

Noninvasive imaging and endoscopy play important and complementary roles in the diagnosis and management of patients with pancreatic cancer. Imaging, primarily in the form of ultrasonography (US) and CT, is often the first line of investigation for the symptoms of pancreatic cancer. Imaging is widely available and can provide noninvasive diagnostic and staging information, while endoscopy offers complementary diagnostic and therapeutic tools throughout the spectrum of care. The following sections examine the roles and importance of each of these modalities for pancreatic cancer.

Noninvasive imaging in pancreatic cancer

Image-Based Anatomy of the Pancreas

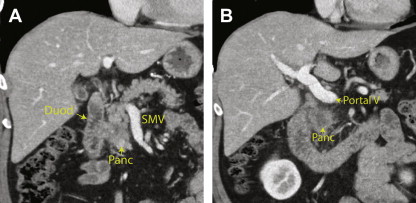

As shown in Fig. 1 , the pancreas is conceptually divided into 4 parts based on adjacent landmarks, as follows:

- •

Head: The head is the rightmost portion of the pancreas. All parenchyma to the right of the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) is included in the pancreatic head. The head contains the common bile duct and central portion of the pancreatic duct.

- •

Neck: The pancreatic neck is a narrow band of tissue that is located anterior to the SMV. This part is defined medially by the right edge of the portal vein and laterally by the left edge of the portal vein-SMV confluence.

- •

Body: The body of the pancreas is located lateral to the left edge of the portal vein-SMV confluence. While the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) manual states that the left edge of the aorta is the dividing line between the body and tail, this often results in little or no parenchyma in the body and is not uniformly accepted. The empirical division is often chosen to be 2 to 3 cm to the left of the aorta.

- •

Tail: The tail of the pancreas is the most lateral component and all pancreatic tissue lateral to the pancreatic body. The tail is typically located near the splenic hilum.

In addition, the uncinate process is a small, variable projection of the pancreatic head that extends posterior to the SMV.

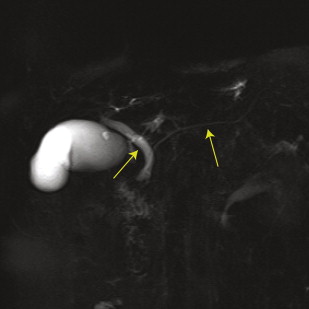

Ductal anatomy

There are 2 ductal systems that traverse the pancreas: the pancreatic ducts and the common bile duct. Fig. 2 shows the typical configuration of these ductal systems within the pancreas.

The common bile duct is formed from the fusion of the proper hepatic duct and the cystic duct, which occurs superior to the pancreas in most people. In standard anatomy, the common bile duct traverses the pancreatic head and merges with the pancreatic duct before draining through the sphincter of Oddi at the ampulla of Vater.

The main pancreatic duct begins in the tail of the pancreas and extends through the body and neck of the pancreas (see Fig. 2 ). The main pancreatic duct typically extends inferomedially through the pancreatic head as the ventral duct of Wirsung. The dorsal duct of Santorini fuses with and drains into the main duct during typical embryologic development. Common variants of this configuration are described by Yu and colleagues.

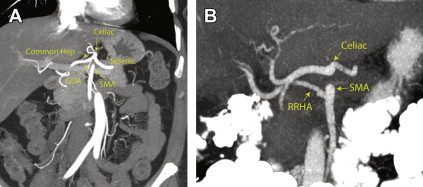

Vascular anatomy

Correct identification of the vessels in and around the pancreas is critical to assessing the feasibility of surgery for pancreatic cancer. There is substantial variability in the arterial anatomy in this region, so the radiologist plays a key role in delineating each patient’s anatomy for the surgical oncology team.

Table 1 describes the arterial segments that are most important in pancreatic cancer. As shown by Winston and colleagues, up to 49% of patients have variations in one of the important arteries that can be involved in a pancreatic resection. Fig. 3 shows the typical arterial anatomy on CT angiograms. Detailed and accurate reporting of these variations is crucial for preoperative planning studies.

| Artery | Standard Origin | Variants |

|---|---|---|

| Celiac axis | Aorta | Common trunk with SMA (<1%) |

| Left gastric | Celiac axis | Aortic origin (3%) |

| Splenic | Celiac axis | –– |

| Common hepatic | Celiac axis | SMA origin (2%), aortic origin (2%) |

| GDA | Common hepatic | SMA origin (<1%), right hepatic origin (<1%) |

| Proper hepatic | Common hepatic (at origin of GDA) | Immediate trifurcation of common hepatic (4%) |

| Left hepatic | Proper hepatic | Left gastric origin (13%), common hepatic (<1%), celiac axis (<1%) |

| Right hepatic | Proper hepatic | SMA origin (15%), celiac axis (4%), GDA origin (1%), aorta (<1%) |

| Accessory hepatic | Not typically present | Numerous, primarily from contralateral hepatic (5%) and left gastric (4%) |

| SMA | Aorta | Common trunk with celiac (<1%) |

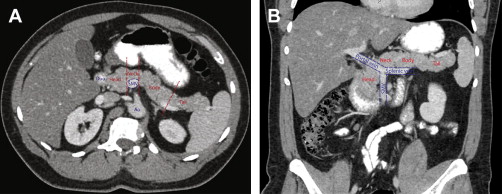

The detailed venous anatomy around the pancreas is less crucial for surgical planning, but 3 major veins must be assessed to determine resectability ( Fig. 4 ). The SMV drains the small bowel and colon. The SMV is located at the lateral border of the pancreatic head and is immediately posterior to the pancreatic neck. The SMV merges with the splenic vein, which travels along the posterior margin of the tail, body, and neck of the pancreas, to form the portal vein. The portal vein then travels superiorly and to the right to the hepatic hilum.

Adjacent structures

The anterior and superior margins of the pancreas are covered by the peritoneum of the lesser sac, so lesions that extend anteriorly or superiorly may involve the peritoneal cavity and metastasize through that pathway. A narrow fold of the transverse mesocolon extends anteriorly and inferiorly from the lower anterior margin of the pancreas and forms the inferior boundary of the lesser sac; this can be a direct retroperitoneal pathway of spread of cancer and is the mechanism through which the colon obstruction sign is observed on kidney-ureter-bladder (KUB) films in patients with pancreatic pathology.

The anterior, inferior margin of the uncinate process, body, and tail of the pancreas are in close proximity to the greater sac of the peritoneum as well as the root of the mesentery. Tumor that extends anteriorly and inferiorly from this area can spread along the mesentery around the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and SMV (as in Fig. 12 D) or may directly invade into the peritoneum.

The inferior margin of the pancreas is retroperitoneal and is bordered by the duodenum. The posterior margin is also retroperitoneal and is bordered by the inferior vena cava, aorta, left adrenal gland, and left kidney. Lesions arising from the uncinate process or posterior body and tail may extend along these planes and sometimes metastasize into the left perirenal space.

Imaging Techniques

The following noninvasive imaging techniques are typically used in the evaluation of pancreatic cancer:

- •

CT

- ○

CT is the primary method of abdominal imaging

- ○

This technique uses X-rays to create images of thin sections of the body

- ○

CT is typically performed using intravenous iodinated contrast

- ○

Standard studies are performed with a single scan acquired in the portal venous phase, approximately 70 seconds after the start of contrast injection

- ○

Specialized pancreatic cancer protocols typically involve the following 3 scans after contrast injection:

- ▪

Early arterial phase scan for assessment of arterial anatomy for surgery (25 seconds after injection)

- ▪

Late arterial/pancreatic parenchymal phase scan for detection of pancreatic lesions and venous anatomy (at 40–45 seconds)

- ▪

Portal venous phase scan for assessment of regional and metastatic disease, particularly in the liver (at 70 seconds)

- ▪

- ○

- •

MRI

- ○

This technique uses a combination of strong magnetic fields and nonionizing radiowaves to produce images of the body

- ○

MRI is a problem-solving modality; it can detect and characterize lesions that may be occult or indeterminate on other modalities

- ○

Each MRI sequence exploits a different combination of physical characteristics to produce contrast between tissue types

- ○

MRI of the pancreas is typically performed with intravenous gadolinium contrast

- ▪

Oral contrast such as water or milk can be used to improve visualization of the gastric and duodenal margins near the pancreas

- ▪

- ○

A typical MRI of the pancreas includes T2-weighted sequence, heavily T2-weighted magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), T1 precontrast sequence, multiphase postcontrast sequence, and diffusion-weighted sequence; views should be acquired in at least 2 planes

- ○

Secretin injection can be used to augment ductal dilatation in MRCP when strictures or main duct communication are questioned

- ○

The typical appearance of the pancreas on MRI is demonstrated in Fig. 5

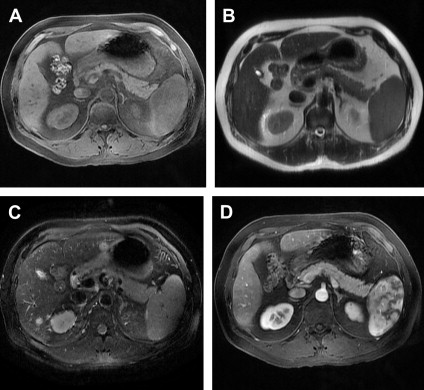

Fig. 5

Normal appearance of the pancreas on MRI. The normal pancreas is hyperintense on precontrast T1-weighted images ( A ) and mildly hypointense on T2-weighted images ( B ) without fat saturation, and ( C ) with fat saturation. Normal parenchyma shows increased signal on postcontrast images ( D ); appearance of spleen is due to phase contrast.

- ○

- •

US

- ○

This method uses high-frequency sound waves to image the structure of tissues of interest

- ○

US is often used to assess for biliary or gallbladder pathology during initial evaluation of symptoms

- ○

Transabdominal US of the pancreas can be limited by gastric and duodenal air

- ○

US is a relatively low-cost and accessible technique, but performance and interpretation depend highly on the skill of the sonographer and radiologist

- ○

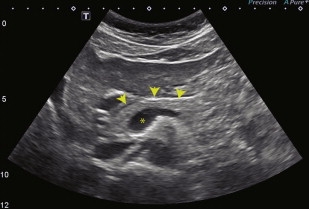

The typical appearance of the pancreas on US is demonstrated in Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Normal appearance of the pancreas on US. This transverse US image shows the typical homogeneously echogenic appearance of the pancreatic head, neck, and proximal body ( arrowheads ). The anechoic portal confluence is visible centrally ( asterisk ), and a portion of the splenic vein extends leftward from the confluence along the posterior margin of the pancreas.

- ○

- •

PET

- ○

PET produces images of positrons that are created by radioactive decay

- ○

PET uses radiotracers, which are compounds labeled with a radioactive atom, that localize to a process or structure of interest

- ▪

FDG, an analog of glucose and a marker of energy metabolism, is the most commonly used radiotracer

- ▪

- ○

PET is often coupled with low-dose CT for correction of attenuation within the body

- ○

This technique is highly sensitive to sites of disease throughout the body and is often used for systemic staging in cancer care

- ○

- •

Radiography and fluoroscopy

- ○

These methods use X-rays to create projection images of the body

- ○

These techniques are of limited use in modern pancreatic cancer diagnosis and treatment

- ○

Historically, abdominal radiographs and barium enemas could show transverse colon obstruction from spread of pancreatic cancer along the transverse mesocolon

- ○

Imaging Across the Spectrum of Care

Initial diagnosis

The initial assessment of the symptoms of pancreatic cancer often begins with a diagnostic CT or US examination. The initial diagnostic use of these modalities is as follows:

- •

CT is the preferred diagnostic modality because it can be used to assess for the local, regional, and systemic signs of disease and has utility for a wide range of alternative diagnoses.

- •

US is often used as an initial study in patients who present with right upper quadrant pain or jaundice because of its sensitivity for biliary tract obstruction and for the alternative diagnosis of choledocholithiasis.

- •

MRI is used as a problem-solving tool when the initial diagnosis is uncertain because of the modality’s superior soft tissue contrast and ability to characterize the structure and composition of unknown lesions.

- •

PET-CT is not typically part of the initial diagnostic strategy but may rarely be used for detection of an occult primary tumor when a patient has systemic signs of malignancy (eg, cachexia) without localizing symptoms.

When a pancreatic lesion is detected on the initial diagnostic workup, there are a variety of benign and malignant differential considerations that should be entertained. The most common considerations and their diagnostic features are as follows:

- •

Adenocarcinoma (see Fig. 12 )

- ○

Ill-defined, hypodense, infiltrative mass on CT

- ○

Solid (except carcinomas arising from cystic pancreatic lesions)

- ○

Hypoechoic, nonshadowing mass on US

- ○

T1-hypointense and minimally T2-hyperintense appearance of the primary mass on MRI

- ○

Hypoenhancing on postcontrast pancreatic and portal venous phases

- ○

Mildly restricted diffusion on diffusion-weighted imaging

- ○

Significant FDG avidity

- ○

Hepatic and peritoneal metastases are common

- ○

- •

Neuroendocrine tumors, including carcinoids ( Fig. 7 )

- ○

Arterial and pancreatic phase hyperenhancement on CT and MRI

- ○

Washout of contrast on delayed imaging

- ○

T1 hypointensity or isointensity of the mass to pancreas and T2 hyperintensity on MRI

- ○

Typically solid, but rare complex cystic variants are seen

- ○

Restricted diffusion on diffusion-weighted MRI

- ○

Variation of FDG uptake by grade

- ○

Hepatic metastases are common

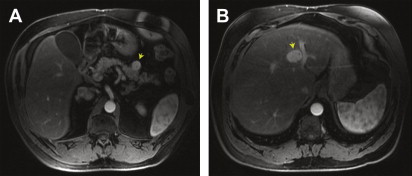

Fig. 7

Multiple gastrinomas in a patient with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. MRI of the pancreas demonstrates a representative example of several well-circumscribed hypervascular lesions ( arrow ) that were seen throughout the pancreas ( A ). A hypervascular liver metastasis was also identified ( B ) ( arrow ). The serum gastrin level was elevated to 20,140 pg/mL (normal < 100 pg/mL). Hyperparathyroidism was also present.

- ○

- •

Cystic pancreatic neoplasms

- ○

Mixture of solid and fluid density components on CT

- ○

May have a capsule or calcifications

- ○

MRI shows T2-hyperintense cystic components with enhancing mural nodules or septations

- ○

MRCP can be used to show relationship to pancreatic duct

- ○

Entities include mucinous cystic tumors, serous cystadenomas (most commonly microcystic), solid pseudopapillary epithelial neoplasms, intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN; main duct or sidebranch varieties; Fig. 8 ), and rare cystic neuroendocrine tumors

Fig. 8

IPMN of the head of the pancreas. Pancreatic phase CT demonstrates a 2.7-cm cystic mass in the head of the pancreas that is confluent with the main pancreatic duct. This lesion was resected and found to contain areas of moderate dysplasia.

- ○

- •

Metastases

- ○

Uncommon overall, but most commonly associated with renal cell carcinoma, melanoma, as well as lung and breast cancers. Fig. 9 shows a rare solitary pancreatic metastasis from a colorectal adenocarcinoma.

Fig. 9

Colorectal cancer metastasis mimicking pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Portal venous phase CT ( A ) demonstrates a 3.7-cm hypodense solid mass in the head of the pancreas. MRI of the pancreas shows a hypoenhancing mass ( B ) that is hyperintense on T2-weighted images ( C ). A previous US ( D ) demonstrated a hypoechoic, nonshadowing mass at this location.

- ○

Variable appearance on CT, MRI, and PET-CT depending on the primary source

- ○

Synchronous metastases are typically present elsewhere in the body

- ○

- •

Pancreatitis

- ○

CT shows ill-defined, homogeneous hypodensity with loss of internal parenchymal architecture ( Fig. 10 )

Fig. 10

Acute pancreatitis. Portal venous phase CT ( A ) demonstrates diffuse fat stranding around the head and uncinate process of the pancreas. No distinct mass is seen. A coronal view from the same CT ( B ) shows that the parenchymal architecture of the pancreas is preserved, which suggests an inflammatory process rather than an invasive adenocarcinoma.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

- ○