Figure 201.1 Life cycle of Ixodes scapularis. (Reproduced with permission from D. W. Miller.)

Figure 201.2 Ixodes scapularis (also known as Ixodes dammini) ticks showing larval, nymphal, and adult stages.

Beginning in the 1980s, human babesiosis has been described with increasing frequency at sites in the northeastern and northern midwestern United States. Recent studies suggest that the endemic range continues to expand. In certain sites during years of high transmission, babesiosis may constitute a significant public health burden. For example, in one study of a highly endemic area in Rhode Island, approximately 9% of the population had serologic evidence of previous B. microti infection compared with 11% of previous Lyme disease. Most human cases of babesiosis occur in the summer and in areas where the vector tick, rodents, and deer are in close proximity to humans. Rarely, babesiosis is acquired through transfusion of blood products, including whole blood, packed red cells, cryopreserved red cells, and platelets. Transplacental/perinatal transmission of babesiosis has also been described.

Pathogenesis

Our understanding of the pathogenesis of human babesiosis is incomplete and is primarily based on studies done in animals. Cytoadherence of infected erythrocytes to vascular epithelium may diminish access of host immune factors to babesia. Cytoadherence may prevent transit of infected erythrocytes through the spleen where they would be destroyed, thus allowing babesia to complete their life cycle and invade other erythrocytes. Excessive cytoadherence may lead to erythrocyte sequestration and obstruction of microvasculature with subsequent tissue anoxia, as has been demonstrated in cattle infected by B. bovis. Similarly, production of host proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin (IL)-1 help to destroy intracellular babesia; however, excessive cytokine production associated with moderate to severe disease probably accounts for the majority of clinical manifestations and complications of the disease. T cells, B cells, macrophages, neutrophils, antibody, and complement also are important in clearing parasitemia and may contribute to disease pathogenesis.

Clinical manifestations

The clinical severity of babesiosis ranges from subclinical infection to fulminating disease resulting in death. In clinically apparent cases, symptoms of babesiosis begin after an incubation period of 1 to 9 weeks from the beginning of tick feeding or 6 weeks to 6 months after transfusion. In most cases, there is a gradual onset of malaise, anorexia, and fatigue followed by intermittent temperatures as high as 40°C (104°F) and one or more of the following symptoms: chills, sweats, myalgia, arthralgia, nausea, and vomiting. Less commonly noted are emotional lability, hyperesthesia, headache, sore throat, abdominal pain, conjunctival injection, photophobia, weight loss, and nonproductive cough. The findings on physical examination generally are minimal, often consisting only of fever. Mild splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, or both are noted occasionally. Slight pharyngeal erythema, jaundice, retinopathy with splinter hemorrhages, and retinal infarcts also have been reported. Rash is seldom noted, although ecchymoses and petechiae have been described in severe disease.

Symptoms usually persist for a few weeks to several months, with prolonged recovery of up to 18 months in severe cases. Parasitemia may continue even after a person feels well and may persist for >2 years with subsequent relapse of illness. Although prolonged symptomatic disease unresponsive to antimicrobial therapy or death may occur in immunocompromised hosts, complete recovery with or without therapy is the rule.

Patients at increased risk for more severe babesial disease include those with malignancy, concomitant human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, asplenia, age greater than 50 years, immunosuppressive medication regimens, or infection with B. divergens or B. duncani. Concurrent babesiosis and Lyme disease infection occurs in about 3% to 15% of patients experiencing Lyme disease in parts of southern New England and results in more severe acute Lyme disease illness. Moderate to severe babesiosis may occur in children, but infection often results in mild disease and is generally less debilitating than in adults. Several cases of neonatal babesiosis have been described, usually following transfusion with infected blood, and sometimes resulting in severe illness. Symptoms and signs include lethargy, tachypnea, pallor, poor feeding, splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, jaundice, and generalized macular rash.

Complications

A severe form of babesiosis has been noted in some patients, consisting of fulminant illness lasting about a week and ending in death or a prolonged convalescence. Although more common in immunocompromised hosts or those experiencing B. divergens or B. duncani infection, severe babesiosis can occur in otherwise healthy individuals who are infected with B. microti. In a retrospective study of 136 patients with B. microti infection from Long Island, New York, 7 patients (5%) died. The patients with fatal illness ranged in age from 60 to 82 years, and only one was known to be immunocompromised. Signs and symptoms in severe cases include high fever, severe hemolytic anemia, hemoglobinemia and hemoglobinuria, jaundice, ecchymoses, petechiae, congestive heart failure, pulmonary edema, renal failure, adult respiratory distress syndrome, and coma. Patients with asplenia, malignancy, and/or HIV infection may experience a chronic form of babesiosis that is unresponsive to multiple courses of standard antibabesial therapy.

Diagnosis

Babesiosis should be suspected in any patient with unexplained febrile illness who has recently lived or traveled in endemic regions during the months of May through September, with or without a history of tick bite. There is often no recollection of a tick bite, because the unengorged I. scapularis nymph is difficult to discern with the naked eye (~2 mm in length). Babesiosis also should be suspected in any patient with unexplained febrile illness who has had a blood transfusion within the previous 6 months.

Laboratory findings reflect the invasion and subsequent lysis of erythrocytes by the parasite and the immune response to infection. They include moderate to severe hemolytic anemia, an elevated reticulocyte count, thrombocytopenia, an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, elevated serum bilirubin and liver enzyme concentrations, elevated serum blood urea nitrogen and creatinine concentrations, and proteinuria. The leukocyte count is normal to slightly decreased, with a “left shift.” Atypical lymphocytes also may be noted on manual differential blood smear examination.

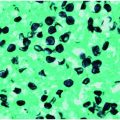

Specific diagnosis of babesiosis is made by microscopic demonstration of the organism using Giemsa-stained thin blood smears. Giemsa-stained Babesia parasites appear as round, oval, or pear-shaped microorganisms with a blue cytoplasm and a red chromatin membrane (Figure 201.3). Multiple blood fields should be examined because only a few erythrocytes are infected in the early stage of the illness when most people seek medical attention. Fewer than 1% of erythrocytes may be parasitized initially and may escape detection. Maximum erythrocyte infection is approximately 10% in normal hosts but up to 85% in people who are immunocompromised. Thick blood smears may be examined, but the organisms appear as simple chromatin dots that may be mistaken for stain precipitate or iron inclusion bodies. Accordingly, only someone with extensive experience in interpreting thick smears should perform this method. The ring form is most common and is very similar to the intraerythrocytic ring forms of Plasmodium falciparum

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree