Chapter 44 Histoplasmosis

INTRODUCTION

Histoplasmosis is a serious opportunistic infection in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) in endemic regions of America, Africa, and Asia, although cases often are diagnosed outside the endemic regions in individuals who previously resided or traveled in endemic areas.1 Since the introduction of potent treatment for HIV infection, the incidence of histoplasmosis has declined, and the potential for cure has improved. The clinical manifestations range from localized pulmonary disease in patients with higher CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts to widespread disseminated disease in those with more advanced HIV infection. Prompt diagnosis requires awareness of the clinical manifestations, a high index of suspicion, and familiarity with the diagnostic tests. If the diagnosis is established before the disease becomes severe, antifungal therapy with liposomal amphotericin B or itraconazole is highly effective. In patients achieving a good immunologic response to antiretroviral agents, lifelong suppressive therapy is no longer required.

CLINICAL FINDINGS

Histoplasmosis is acquired by inhalation of microconidia of the mold phase of the organism following disturbance of soil or accumulations of bird or bat droppings containing the organism. Disease manifestations following acute exposure range from asymptomatic infection in otherwise healthy individuals inhaling a small number of microconidia to life-threatening acute pulmonary disease in those inhaling a large number of spores.2 While subclinical, nonprogressive hematogenous dissemination occurs following acute pulmonary histoplasmosis, most patients recover without treatment with development of a cell-mediated immune response during the first month following infection. Chronic pulmonary disease may occur in patients with emphysema, and progressive disseminated disease in those who are immunosuppressed. In patients with HIV infection, a similar spectrum of disease, ranging from asymptomatic or acute pulmonary infection in patients with CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts above 300 cells/mm3 to severe progressive disseminated histoplasmosis (PDH) in those with lower CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts.

Progressive Disseminated Histoplasmosis

Progressive disseminated disease occurs in 95% of cases of histoplasmosis in patients with AIDS, but localized pulmonary disease may be seen in those with CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts above 500 cells/mm3.3,4 About 90% of cases of PDH have occurred in patients with CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts below 200 cells/mm3, and usually below 50 cells/mm3. Patients present with fever, fatigue, and weight loss, and half or more exhibit respiratory symptoms. Common physical findings include hepatosplenomegaly and lymphadenopathy. The course may be rapidly fatal, but a subacute presentation over 1–3 months is more characteristic.

Radiographic abnormalities are present in half to two-thirds of cases.3,5,6 The radiographic findings are usually diffuse and include nodular or linear opacities, or air-space disease in most cases. Calcified lymph nodes or lung lesions are noted in a third of cases, while mediastinal lymphadenopathy is uncommon (<5%).3,6

Patients infrequently (<10%) present with shock, respiratory insufficiency, and hepatic and renal failure.4 The sepsis presentation represents a late manifestation, usually occurring in patients who delayed seeking care until they were severely ill. Nearly half of patients who present with a sepsis-like illness die within a week of diagnosis.

Central nervous system involvement occurs in ∼15% of cases.3,4 Patients may present with lymphocytic meningitis, focal brain lesions, or diffuse encephalitis.7,8 Patients complain of fever and headache and often demonstrate mental status changes. Seizures or focal neurologic deficits may occur in patients with brain involvement. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) typically shows lymphocytic pleocytosis, protein elevation, and hypoglycorrhachia in those with meningitis. Single or multiple enhancing brain lesions may be seen by CT scans or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in patients with cerebral involvement. The prognosis is worse in patients with neurologic findings than in those without these complications.3

Gastrointestinal manifestations including diarrhea, abdominal pain, intestinal obstruction or perforation, bleeding, or peritonitis complicate ∼10% of cases.9 A spectrum of lesions, including plaques, ulcerations, pseudopolyps, small (3–8 mm) nodules, thickened intestinal folds, luminal masses, and strictures may occur anywhere along the gastrointestinal tract but are more common in the small intestine and right colon. Colonic disease may be misdiagnosed as malignancy or inflammatory bowel disease.10 Omental and mesenteric nodules causing peritonitis and ascites have been reported. Perforation also has occurred resulting from transmural necrosis of the small intestine. Biopsies of intestinal lesions show necrotizing granulomas containing yeast forms of Histoplasma capsulatum.

Dermatologic findings, seen in 10% of cases, include erythematous or hyperpigmented papules, pustules, folliculitis, plaques with ulcerations, nodules, eczematous changes, erythema multiforme, and rosacea-like rashes. Skin lesions appear to be more common in patients from South America.11 H. capsulatum organisms may be seen in biopsies of skin lesions, providing a rapid diagnosis. Rare manifestations include adrenal insufficiency, pericarditis, pleuritis, pancreatitis, prostatitis, and retinitis.

An immune reconstitution syndrome may be seen in patients responding to antiretroviral therapy.12,13 Manifestations including splenic infarction, ulcerative skin lesions;12 liver abscess, lymphadenitis, intestinal obstruction, uveitis, and arthritis.13

TAXONOMY

H. capsulatum var capsulatum is an ascomycete whose teleomorphic state is Ajellomyces capsulatus. It is classified in the family Arthrodermataceae, order Onygenales of the Ascomycotina. H. capsulatum variety capsulatum contains several clades, which differ in geographic distribution. Clade 2 is most common in the US, and 5 and 6 in Central and South America.14 Other varieties include H. capsulatum var duboisii and farciminosum, which cause different disease syndromes than seen with H. capsulatum var capsulatum and rarely cause PDH in patients with AIDS. Although H. capsulatum variety duboisii is endemic in equatorial Africa, most infections in patients with AIDS in Africa are caused by var capsulatum.1

BIOLOGY

Histoplasma capsulatum grows as a mold in the soil and is found primarily in microfoci containing large amounts of rotted guano where birds have roosted or bats have inhabited. The mold is comprised of hyphae bearing large tuberculate macroconidia (8–14 μm in diameter), which are characteristic of H. capsulatum, and smaller microconidia (2–5 μm), which are the infectious form of the organism. It causes infection when conidia are inhaled. At temperatures above 35°C H. capsulatum grows as a yeast measuring 2–3 × 3–4 μm in diameter. The yeast form is typically found in infected tissues. While reactivation has been proposed as the cause for PDH in AIDS, the low incidence of histoplasmosis in patients with AIDS in most endemic areas (<3%), where histoplasmin skin test positivity exceeds 50%, indicates that reactivation is rare. Pulmonary calcification, a hallmark of past histoplasmosis, was not a risk factor for clinical disease,15 providing added evidence against reactivation. Occurrence of PDH in patients with AIDS who have calcified lesions in the lungs, rather than indicating reactivation, suggest re-infection in persons with waning immunity during progressive HIV infection.3,4 The strongest evidence supporting reactivation was by demonstration of DNA patterns typical of Panamanian strains of H. capsulatum in Puerto Rican immigrants in New York City,16 but travel information was insufficient to exclude more recent acquisition while visiting Latin America.

Cellular immunity plays a key role in defense against H. capsulatum.17 With development of specific T-cell-mediated immunity, cytokines including tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interferon-g, and interleukin-12 (IL-12) arm macrophages to kill the fungus and halt progression of the disease. The importance of TNF-α in defense against H. capsulatum is shown by the occurrence of PDH in patients with rheumatologic disorders or Crohn’s disease treated with TNF-α blockers.18 If cell-mediated immunity is impaired, an appropriate immune response to the infection cannot occur, leading to a progressive disseminated infection.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

PDH occurs in 1–5% of patients with AIDS from endemic areas. During outbreaks, however, the incidence of PDH has exceeded 25% in some US cities.4 Rates above 5% also have been reported in some Latin American countries, as recently reviewed.19 PDH occurs in fewer than 1% of patients from nonendemic areas. Cases reported in Europe usually were acquired in Africa, Latin America, and Asia, although there are areas in Europe where autochthonous infection may occur.1 The incidence in the US has declined since HAART became available, and now most cases occur in patients with undiagnosed HIV infection or who are failing HAART.

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis of PDH requires a high index of suspicion and an understanding of the clinical and laboratory findings.20 The diagnosis should be suspected in patients with unexplained fever and weight loss. Radiographic findings of diffuse reticulonodular or miliary infiltrates also suggests the diagnosis.6 Laboratory abnormalities may include anemia, thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, and hepatic enzyme elevation. A reactive hemophagocytic syndrome, consisting of fever, thrombocytopenia, and bone marrow histology exhibiting hemophagocytic phagocytosis, usually in association with markedly elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and ferritin, has been reported in patients with a sepsis-like presentation,21 but is nonspecific.

LDH elevation is present in 90% of patients,5 but may be seen in Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia and disseminated Mycobacterium infection. In fact, in one report P. jiroveci pneumonia and disseminated tuberculosis, but not PDH, were associated with LDH elevation after controlling for race and CD4+ T-lymphocyte count.22 Ferritin elevation has been reported in PDH, but also is not specific; and while a marked elevation >10 000 ng/mL is more specific for PDH,23 the sensitivity at that cutoff is unknown.

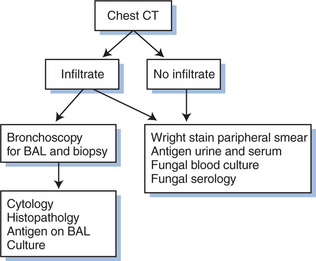

In half to two-thirds of cases, pulmonary involvement is present. Bronchoscopy is recommended in such patients to assist in rapid diagnosis of PDH and exclude co-infection, which is not uncommon. An approach to evaluation in patients with pulmonary symptoms or CT abnormalities is outlined in Figure 44-1.

A battery of laboratory tests are useful for diagnosis of PDH, and their sensitivities are summarized in Table 44-1. Of note is that none of these tests are positive in all cases, and that, except for culture, positive results may be false-positive. Accordingly these tests should be used as an aid to diagnosis, in conjunction with clinical findings and corroborated by other tests, when possible.20

Table 44-1 Sensitivity of Diagnostic Studies in Disseminated Histoplasmosis in Patients

| Test | Percent Positive | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Blood smear | 12–31% | Casanova-Cardiel et al25 |

| Kurtin24 | ||

| Histopathology | 41% | Williams et al26 |

| Antigen urine | 95% | Williams et al26 |

| Antigen serum | 85% | Williams et al26 |

| Antigen CSF | 66% | Wheat et al3 |

| Antigen BAL | 70% | Wheat et al27 |

| Serology | 67% | Williams et al26 |

| Culture | 85% | Wheat et al3 |

| Williams et al26 |

Direct Detection

Cytopathology or histopathology using a variety of techniques (Papanicolaou, Giemsa, Gram, hematoxylin and eosin, Wright, Gomori methenamine silver (GMS)) reveals yeast measuring ∼3 μm in diameter, with occasional buds. Yeast may be seen by Wright stain of blood smears in up to one-third of cases with severe manifestations (Table 44-1).21,24,25 Yeast may be identified more easily using special fungal stains such as GMS. The highest yield is from bone marrow, positive in 50–75% of patients in which the procedure is performed.3 Overall, however, the sensitivity of histopathology is below 50%.3,26 Candida glabrata, Penicillium marneffei, Toxoplasma gondii, P. jiroveci, and staining artifacts may be misidentified as H. capsulatum.

Antigen Detection

Detection of antigen in body fluids is very useful for diagnosis of PDH in patients with AIDS.20 Antigen is detected in the urine of 95% and the serum of 85% of patients (Table 44-1).3,26 Antigen may be detected in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid27 and CSF3 of patients with pulmonary or meningeal involvement. Tests for antigen may be falsely negative in patients with mild clinical manifestations or localized sites of dissemination and positive in those with systemic mycoses caused by organisms that contain cross-reactive antigens (Blastomyces dermatitidis, Penicillium marneffei, Paracoccidioides braziliensis). Antigen declines with effective treatment28–30 and increases with relapse,31 providing a useful method to monitor therapy.

Identification of false-positive results in organ transplant recipients caused by human anti-rabbit antibodies, induced in response to treatment with rabbit anti-T-lymphocyte antibody32 led to modification of the Histoplasma antigen assay. Those modifications were incorporated into a second-generation Histoplasma assay in 2004, in which false-positivity caused by human anti-rabbit antibodies was reduced by 95%, and sensitivity in false-negative specimens improved by 73%. The second-generation assay has replaced the original assay for clinical testing at MiraVista Diagnostics. Sensitivity and specificity using the second-generation assay is assumed to be higher than previously reported,20 and studies are in progress comparing the second-generation assay and the original assay.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree