Definition

Herpes zoster is a neurocutaneous disease that is caused by the reactivation of varicella-zoster virus (VZV) from a latent infection of dorsal sensory or cranial nerve ganglia following varicella or primary infection with VZV earlier in life. Herpes zoster is characterized by unilateral, dermatomal pain and rash.

Postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) has been defined as any pain after rash healing or any pain from 1 to 6 months after rash onset. Pain experts currently define PHN as pain 90 to 120 days after rash onset to be consistent with established definitions of chronic pain and to eliminate neuropathic pain from acute inflammation. Some experts define the herpes zoster pain trajectory as an acute herpetic neuralgia that lasts for approximately 30 days after rash onset, a subacute herpetic neuralgia that lasts from 30 to 120 days after rash onset, and PHN as pain that persists 120 days and more after rash onset.

Epidemiology

VZV is a double-stranded DNA that is transmitted from person to person via direct contact, airborne or droplet nuclei when a virus-naïve, VZV seronegative individual is exposed to the vesicular rash of varicella or herpes zoster. These exposed individuals may then develop varicella. Health care workers and staff in nursing homes and hospitals and children who have not received the varicella vaccine may not have had VZV primary infection and are potentially at risk for varicella. However, nearly all older adults are seropositive and latently infected with VZV. The exposure of a latently infected individual to herpes zoster does not cause herpes zoster or varicella. Furthermore, there is no risk of VZV transmission when the herpes zoster rash is only maculopapular or crusted. All cases of herpes zoster are caused by the reactivation of endogenous VZV.

In general population studies from North America and Europe, the incidence of herpes zoster in persons of all ages is 1.2 to 4.8 cases per 1000 persons per year and in persons older than 60 years old, the incidence is 7.2 to 11.8 cases per 1000 per year. The lifetime incidence of herpes zoster is estimated to be about 20% in the general population and maybe as high as 50% among those surviving to 85 years or higher.

The cardinal epidemiological feature of herpes zoster is its increase in incidence with aging and with diseases and drugs that impair cellular immunity. The increase in the likelihood of herpes zoster with aging starts around 50 to 60 years of age and increases into late life in individuals older than 80 years of age (Figure 129-1). In the herpes zoster vaccine trial (“Shingles Prevention Study”), which was prospective, used active surveillance in a community-based population, and used polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for definitive diagnosis of herpes zoster cases, the incidence of herpes zoster in the placebo group (n = 19 276) was 11.8 cases per 1000 persons per year in adults 60 years of age and older. Immunocompromised patients at risk for herpes zoster include persons with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, Hodgkin’s disease, non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas, leukemia, bone marrow and other organ transplants, systemic lupus erythematosus, and those taking immunosuppressive medications. Other risk factors include white race, psychological stress, and physical trauma.

Figure 129-1.

Incidence of zoster and postherpetic neuralgia by age. (Data from Donahue JG, Choo PW, Manson JE, et al. The incidence of herpes zoster. Arch Intern Med.155:1605–1609, 1995; Choo PW, Galil K, Donahue JG, et al. Risk factors for postherpetic neuralgia. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:1217–1224.)

Current population figures and herpes zoster incidence data yield estimates of about 1 million new cases of herpes zoster each year in the United States, with more than half occurring in persons 60 years of age or older. The number of herpes zoster cases is expected to increase in the near future decades because of population aging and the development of immunocompromising diseases (and their therapies) associated with aging. Whether varicella vaccination of children and the subsequent reduction in varicella incidence will contribute to an increase in the number of herpes zoster cases by reduced exogenous immune boosting in individuals latently infected with wild-type VZV is under investigation.

Exact data on the incidence and prevalence of PHN are not available because of variable definitions and inadequate data in medical records and administrative databases. Useful figures for older patients who seek medical care come from a combined analysis of large trials of antiviral drugs for herpes zoster in outpatients aged 50 years and older. In this analysis, 49% to 54% of placebo recipients had pain 90 days after rash onset and 46% at 120 days after rash onset; 25% to 35% of antiviral recipients had pain 90 days after rash onset and 29% at 120 days after rash onset. In the placebo group of the Shingles Prevention Study, the incidence of PHN was 0.74 cases per 1000 person-years for subjects between 60 and 69 years and 2.14 for subjects older than 70 years (Figure 129-1). The figure illustrates that the rate of increase of PHN cases associated with aging is greater than the rate of increase of herpes zoster cases. Investigators have estimated that the prevalence of PHN ranges from 500 000 to 1 million in the United States.

Like herpes zoster, the most important epidemiological feature of PHN is its marked increase in incidence and severity with aging. All epidemiological studies of PHN show that the risk of PHN is substantially increased in older adults. Other risk factors for PHN include the presence of prodromal pain, severe pain during the acute phase of herpes zoster, greater rash severity, more extensive sensory abnormalities in the affected dermatome and, possibly, ophthalmic nerve involvement. As the age of patient and severity of the episode of herpes zoster increases, the more likely the development of PHN.

Clinical Features

VZV reactivates in the affected sensory ganglion and spreads in the peripheral sensory nerve, causing symptoms that frequently precede the rash by several days. These prodromal symptoms are located in the involved dermatome and range from a superficial itching, tingling, or burning to severe, deep, boring, or lancinating pain, paresthesia, or hyperesthesia. The pain can be constant or intermittent. The prodrome maybe mistaken for many other conditions in older adults, particularly in those patients with cognitive impairment. The prodrome may mimic pleurisy, a myocardial infarction, cholecystitis, appendicitis, renal colic, a collapsed intervertebral disk, glaucoma, trigeminal neuralgia, or unappreciated trauma. The prodromal symptoms usually last a few days, although it has been reported to last more than a week. Zoster sine herpete is a condition when patients experience acute dermatomal neuralgia without ever developing a skin eruption.

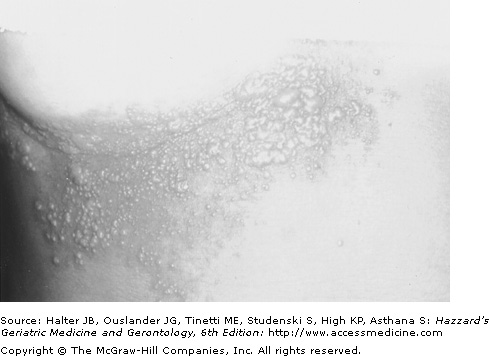

When VZV reaches the dermis and epidermis, the initial cutaneous presentation of herpes zoster occurs as a unilateral, dermatomal, red, maculopapular eruption. Vesicles generally form within 24 hours and evolve into pustules, which dry and crust in 7 to 10 days. The rash usually heals over in 2 to 4 weeks. In normal individuals, new lesions may continue to appear for 1 to 4 days and occasionally for as long as 7 days. The T1 to L2 or V1 dermatomes are most commonly involved (Figure 129-2). Adjacent dermatomes can show satellite lesions but multiple lesions in contiguous dermatomes are not characteristic of herpes zoster. Atypical rashes may occur in older persons. The atypical rash maybe limited to a small patch located within a dermatome or may remain maculopapular without ever developing vesicles.

Herses zoster-associated acute neuritis produces dermatomal neuralgic pain in many older adults. Some older patients never develop pain while others may experience the delayed onset of pain days or weeks after rash onset. The neuritis is described as burning, deep aching, tingling, itching, or stabbing. A subset of patients may develop severe pain, especially those with trigeminal nerve involvement. Acute herpetic neuralgia can have a profound adverse impact on functional status and quality of life in older adults. Acute herpes zoster pain can interfere with all activities of daily living but interference is greatest for instrumental activities of daily living, as well as sleep, general physical activity, and leisure activities. As overall pain burden increases, patients experience poorer physical, role, and emotional functioning.

Ophthalmic herpes zoster occurs in 10% to 15% of the cases. It is second in frequency to thoracic herpes zoster and is a result from VZV reactivation in the first division of the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V). Ophthalmic involvement may present with impaired vision as a result of local inflammation. In 30% to 40% of cases of ophthalmic zoster, there is involvement of the nasociliary branch, which also innervates the side and tip of the nose. Symptoms and/or signs on the tip of the nose should immediately lead to a thorough search for involvement of the eye. VZV-induced damage to the cornea and uvea and other eye structures can cause corneal anesthesia and ulceration, glaucoma, optic neuritis, eyelid scarring and retraction, visual impairment, and blindness in patients who did not receive antiviral therapy. Secondary bacterial infections can cause panopthalmitis and enucleation. Ophthalmic herpes zoster is also associated with stroke occurring weeks to months after the onset of the rash. The cause of the stroke is a granulomatous arteritis of the carotid artery close to the involved first division of cranial nerve V. Arteriograms show segmental narrowing of cerebral arteries ipsilateral to the ophthalmic zoster. Herpes zoster-associated arteritis in the trigeminal distribution can also cause ipsilateral occlusion of the central retinal artery with resultant visual loss.

Herpes zoster can affect cranial nerves other than the first division of cranial nerve V in older adults. Involvement of the third division of cranial nerve V can produce lesions and pain in the mandibular area of the face and in the mouth. Cranial nerve VII and VIII involvement, or Ramsey Hunt syndrome, is characterized by facial palsy in combination with herpes zoster lesions of the ipsilateral external ear, ear canal, tympanic membrane, or hard palate. Symptoms include tinnitus, vertigo, deafness, problems with balance, and facial paresis. Involvement of cranial nerve IX, X may produce pharyngeal or laryngeal lesions and resulting pharyngitis or laryngitis. The patient may have multiple symptoms because more than one cranial nerve can be involved in an attack.

Motor paralysis is reported in 1% to 5% of patients with herpes zoster. Subclinical motor neuron involvement with herpes zoster probably occurs more frequently than reported because muscle weakness in the thoracic and lumbar dermatomes is difficult to appreciate. It results from VZV-induced destruction of motor neurons in the anterior spinal horn or motor radiculitis corresponding to the extension of VZV infection from the involved sensory ganglion. Paralysis involves muscle groups with innervation that is contiguous with that of the affected dermatome.

The most commonly observed affected muscles are those of the face with involvement of the cranial nerve VII and the extremities with herpes zoster of the accompanying dermatome. Painful Bell’s palsy in an older adult strongly suggests herpes zoster. Motor deficits usually occur at the time of or within a few weeks after the onset of the rash. Full or partial recovery of motor function occurs in most patients within months of the onset of weakness but facial palsy has a much lower rate of recovery.

Herpes zoster myelitis, with detection of VZV in the spinal cord or cerebrospinal fluid, has been reported both as a complication of typical herpes zoster and of zoster sine herpete. The incidence of acute symptomatic myelitis and meningoencephalitis is low (0.2–0.5%), although lymphocytic pleocytosis, with or without an increase in the concentration of protein in the cerebrospinal fluid, is a regular feature of uncomplicated herpes zoster.

The most feared complication of herpes zoster among older adults is PHN. PHN patients describe the quality of their pain as burning, throbbing, stabbing, shooting, sharp, aching, gnawing, tiring, or tender. The pain maybe spontaneous and/or stimulus-evoked. Spontaneous pain maybe constant aching or burning and/or brief, intermittent shock-like sensations. Stimulus-evoked pain consists of allodynia or hyperpathia. Allodynia is pain elicited by an innocuous stimulus and is particularly problematic. A cold wind, clothes, or bed sheets against the allodynic skin may cause debilitating pain. Hyperpathia is an exaggerated pain after a mildly painful stimulus. A minor bump of the affected dermatome against an object can cause severe pain that lasts for hours. Patients may experience discomfort that is not described as pain such as numbness or itching. Postherpetic itch can be maddening and appears to be mediated by damage and dysfunction of peripheral and central itch-specific neurons.

PHN greatly interferes with the functional status and quality of life of older adults. Patients can suffer from a variety of constitutional symptoms including chronic fatigue, anorexia, weight loss, and insomnia. PHN is associated with depression and social isolation in older adults. Reduced quality of life and interference with activities of daily living (ADLs) increases significantly as pain severity increases. Instrumental and basic ADLs are all compromised by PHN. For example, the patient with allodynic skin may be forced to avoid bathing or clothing around the affected area. Instrumental ADLs commonly affected include traveling, shopping, cooking, and housework. Studies using standardized pain scales and measures of function and quality of life such as the SF-36, SF-12, EuroQol, and Nottingham Health Profile have shown that PHN significantly interferes with multiple ADLs, reduces health-related quality of life (HRQL), and impairs mental and physical health. Though most people eventually have relief of pain, some are refractory to all treatments and the pain can even get worse over time (see Box 129-1 on Clinical Pearls).

There is no risk of VZV transmission when the herpes zoster rash is maculopapular or crusted i.e., there must be vesicles for VZV transmission |

When Bell’s palsy presents with pain think HZ. Corollary: If a patient presents with a painful facial paresis look in the ipsilateral ear for vesicles (Ramsey Hunt Syndrome). |

A vesicle at the tip of the nose should raise suspicion for ophthalmological HZ |

Acute and convalescent VZV IgG and IgM levels are needed to diagnose zoster sine herpete. |

Increasing severity of pain and rash in herpes zoster increases the probability of developing PHN. |

Patients who claim they have several episodes of shingles probably have HSV; definitive diagnosis requires microbiological testing (e.g., PCR, culture, IFA) |

Diagnosis

In patients who present with prodromal pain and no rash, herpes zoster is often confused with other causes of unilateral, localized pain in older adults, as noted above. One diagnostic clue to the presence of prodromal pain is localized cutaneous sensory abnormalities (e.g., hyperesthesia, dysesthesia) in the affected dermatome. Herpes zoster is easily diagnosed when an older adult patient presents with the typical dermatomal vesicular rash and pain. In the Shingles Prevention Study of the 1308 cases of suspected herpes zoster based upon clinical evaluation, 984 cases were confirmed to be herpes zoster (75%). During the rash phase, herpes simplex has the most similar presentation to herpes zoster. Evidence supporting herpes simplex includes a presentation in a younger population, multiple reoccurrences of lesions, and the absence of chronic pain. The lesions themselves are more difficult to distinguish, particularly when herpes zoster occurs in areas commonly affected by simplex (e.g., oral, genital, buttock lesions). In the Shingles Prevention Study, 3.4% of suspected herpes zoster cases were found to be herpes simplex virus. The differential diagnosis also includes contact dermatitis, burns, and vesicular lesions associated with fungal infections but the history and examination usually makes the distinction clear.

The diagnosis of herpes zoster may need laboratory diagnostic testing when differentiating herpes zoster from HSV infection is necessary, for suspected organ involvement, and for atypical presentations, particularly in the immunocompromised host. The diagnostic tests include viral culture, immunofluorescent antigen (IFA) detection, PCR, and serology (Table 129-1). The best specimen is vesicle fluid, which contains abundant VZV. Lacking vesicle fluid, acceptable specimens include lesion scrapings, crusts, tissue biopsy, or cerebrospinal fluid. Crusts cannot be used for VZV culture. VZV isolation in culture of vesicular fluid is the “gold standard,” but it is slower than other tests and not very sensitive as only 30% to 60% of vesicle culture specimens are positive. VZV antigen detection by IFA tests of vesicle scrapings or tissue biopsies takes hours to get results and is both specific and sensitive. These reasons make IFA the most useful test when specimens are available. Polymerase chain reaction is highly sensitive and so it can be used to test crust or other unusual samples. As the cost of PCR decreases over time, this will likely be the most commonly used test to confirm herpes zoster in the near future. Acute and convalescent VZV IgM and IgG levels maybe useful in making a retrospective diagnosis when there are no peripheral lesions or specimens are inadequate. Tzanck smears suggest herpes zoster when multinucleated giant cells and intranuclear inclusions are seen on slides but this does not differentiate herpes zoster from herpes simplex.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree