CHAPTER 31 Hepatitis C

Epidemiology

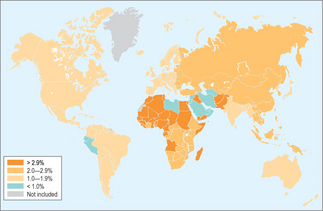

An estimated 123 million people, or 2% of the world’s population, have been infected with hepatitis C virus.1 Few population-based prevalence studies have been published and many of the available data are from surveys of blood donors, outpatients, and other specific subpopulations that are not representative of the general population. These data show a substantial variation from country to country within a region and large differences within individual countries. Prevalence is relatively low (<2%) in the Americas, Europe, and Australia, and intermediate or high (≥ 2%) in developing or transitional countries in Asia and Africa (Fig. 31.1). Prevalence is perhaps highest in Egypt (12% nationally, 40% in some villages),2 where HCV may have been inadvertently spread during schistosomiasis control campaigns that used parenteral therapy with sometimes inadequate infection control measures.2

Figure 31.1 Estimated prevalence of anti-HCV. In this map, prevalences have been estimated for 14 regions of the world defined in the World Health Organization’s The Comparative Quantification of Health Risks (Reference 7).

The map has been modified from Reference 1, with permission of the author.

Injection drug use is an especially strong risk factor for HCV infection because of the high prevalence of chronic infection among injection drug users, frequent sharing of injection equipment among users, and the ease with which HCV is spread by parenteral exposures. In a study in Baltimore in the 1980s, 80% of drug users were infected with the virus within the first year of initiating injection drug use.3 More recent studies have found a lower (10–40% per year) but still substantial rate of infection.4,5 Despite the lower incidence, studies of patients presenting with acute hepatitis C show that injection drug use remains the source of most infections in the United States.

In developing countries, unsafe injection practices may account for most HCV infections.6,7 Surveys in sub-Saharan Africa, for example, have found that 15–20% of injections given for therapeutic purposes within the formal medical system are administered with reused injection equipment that has not been sterilized. In addition, in many developing countries there is a large, informal medical sector where injection practices are undoubtedly worse. There is also a substantial overuse of therapeutic injections where oral therapies could be used or where no pharmacologic therapy is indicated. Household surveys in Romania and Moldova, for example, have found that participants received an average of 5–11 injections per year. Fortunately, injection practices are generally safe in vaccination programs, which are careful to provide adequate supervision and adequate numbers of sterile needles and syringes.

Exposure to HCV through blood transfusion has been extremely rare in developed countries since the implementation of sensitive assays for antibody to HCV (anti-HCV). However, blood banks in developing countries may not test for HCV or may use relatively insensitive rapid diagnostic tests. For this reason, transfusion-transmitted HCV remains a problem. Nosocomial exposure to HCV through needle-stick injuries also occurs and accounts for a relatively small number of infections. For an HCV-contaminated needle-stick injury, the risk of infection (around 1.8%) is intermediate between that for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (0.3%) and hepatitis B virus (HBV) (37–62% if the source patient is hepatitis B e-antigen positive).8 The prevalence of anti-HCV among healthcare workers is not demonstrably different from that among the general population.

Perinatal transmission from HCV RNA-positive mothers occurs at a rate of approximately 6% and is higher if the mother is also infected with HIV.9 There is no clear, consistent evidence that elective cesarean section decreases the rate of transmission. Although HCV can be demonstrated in breast milk, breast-fed infants are at no higher risk of HCV infection than bottle-fed infants.

Etiology

Hepatitis C virus is an enveloped, single-stranded RNA virus of the Flaviviridae family. On environmental surfaces, the virus may remain viable for at least 16 hours but less than 4 days.10 Six genotypes are recognized. Genotype 1 is the most common in many developed countries such as the United States. Certain genotypes have specific geographic distributions, such as genotypes 4 (Egypt), 5 (southern Africa) and 6 (southeast Asia). For patients infected with HCV, the genotype has clinical implications: genotypes 1 and 4 are more difficult to treat and generally require longer courses of therapy than genotypes 2 and 3.11 There are few data on treatment response of other genotypes.

Clinical manifestations and natural history

The other 70–85% of persons with acute HCV infection progress to chronic infection. In long-term follow-up studies of adults with chronic infection, spontaneous clearance of the virus is rare. Chronic infection is generally asymptomatic, although studies have found that it is associated with a lower perceived quality of life.12 Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels fluctuate, often between two and five times the upper limit of normal. In some HCV-infected individuals, ALT levels are persistently normal despite the presence of hepatitis.

A chronic, low-grade hepatic inflammation occurs in most chronically infected persons. Over years, this inflammation results in progressive fibrosis, the end stage of which is cirrhosis. The course of this disease is highly variable: many patients never develop significant fibrosis while a small number develop cirrhosis within a few years. Long-term studies suggest that in the first 20 years, cirrhosis will develop in 5–20% of patients with chronic hepatitis C. There are few data on the progression beyond 20 years.13 Chronic hepatitis C can lead to hepatocellular carcinoma. The latter generally occurs in the setting of cirrhosis and is probably due to fibrosis and regenerative hyperplasia.

Several factors may accelerate the progression of chronic hepatitis C, particularly heavy alcohol use.13 There is no consensus as to whether light and moderate alcohol use are also risk factors for cirrhosis. Infection at an older age and coinfection with HIV are also associated with faster progression. In Egypt, schistosomiasis has been associated with more severe disease.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree