CHAPTER 22 Hepatitis B: Global Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Prevention

Hepatitis B: Clinical Pearls in Refugees and Immigrants

Virology

In the blood of infected individuals, HBV is present in extremely high concentrations, often in viral loads exceeding 107 per milliliter. On environmental surfaces, HBV is highly stable, remaining infectious for at least 1 week.1 Nonetheless, the virus is susceptible to commonly used disinfectants.2

HBV has been sub-classified by two separate classification systems: serotype and genotype. Nine serotypes of HBV have been described on the basis of serologic heterogeneity of HBsAg (adrq+, adrq−, ayr, ayw1, ayw2, ayw3, ayw4, adw2, adw4).3 At least eight genotypes of HBV have been described, designated A through H, on the basis of an 8% difference in nucleotide sequence. HBV serotypes and genotypes vary geographically.4,5

Global Epidemiology

Burden of disease from hepatitis B

Worldwide, hepatitis B virus infection is one of the leading causes of infectious disease-related morbidity and mortality. An estimated two billion people – one-third of the world’s population – have serologic evidence of past or present HBV infection and 350 million people are chronically infected. Each year, an estimated 621 000 people die from HBV-related liver disease (Table 22.1).6 The majority (95%) of these deaths result from the chronic sequelae of infection, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Although most of these deaths occur in adulthood, 21% result from HBV infection acquired in the perinatal period and another 48% from infection acquired in early childhood. Infection acquired after 5 years of age accounts for only 31% of deaths.

Table 22.1 Annual number of hepatitis B-related deaths, by World Health Organization region6

| Region | Number of deaths | Proportion of deaths from chronic infection |

|---|---|---|

| Africa | 69 000 | 90% |

| Americas | 12 000 | 92% |

| Eastern Mediterranean | 21 000 | 90% |

| Europe | 51 000 | 94% |

| Southeast Asia | 143 000 | 92% |

| Western Pacific | 325 000 | 95% |

| Global | 621 000 | 94% |

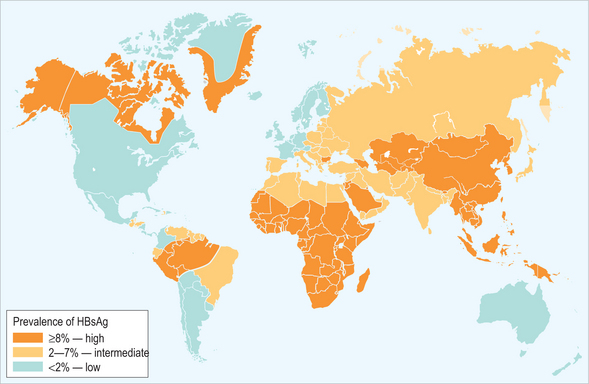

The world can be divided into areas of high, intermediate, and low HBV endemicity based on the prevalence of chronic HBV infection (i.e. the prevalence of HBsAg-positive individuals) in the general population (Fig. 22.1). Approximately 45% of the world’s population lives in countries of high endemicity where > 60% of the population has ever been infected with HBV and > 8% is chronically infected. Most of these countries are in Africa and Asia. In countries of intermediate endemicity, which include 43% of the world’s population, 20–60% of the population has evidence of prior infection and 2–7% is HBsAg-positive. Only 12% of the population lives in countries of low endemicity where the lifetime risk of infection is < 20% and the prevalence of chronic infection is < 2%.

Transmission of hepatitis B virus

Hepatitis B virus is transmitted from person to person through exposure to infected blood or body fluids, including semen and vaginal fluid. Modes of transmission include percutaneous and permucosal exposures to infectious body fluids, sexual contact with an infected person, and perinatal transmission from an infected mother to her infant. Rare instances of transmission of HBV through saliva have been reported.7

Perinatal transmission of HBV occurs from blood exposure during labor and delivery. In utero transmission is relatively rare, accounting for < 3% of perinatal infections in most studies.8–12 The risk of transmission from an infected mother to her infant depends on the HBeAg status of the mother, being 70–90% for infants born to HBsAg-positive/HBeAg-positive mothers and 5–20% for infants born to HBsAg-positive/HBeAg-negative mothers.13–18 Although HBV is found in low concentrations in breast milk, transmission of HBV has not been documented through breast-feeding.19

Horizontal transmission, also known as intrafamilial or household transmission, refers to percutaneous transmission of HBV within the household, from infected family members – most often mothers and older siblings – to young children.20–28 Horizontal transmission is most important in countries of high HBV endemicity, but its occurrence in the United States has also been well documented.29–32 Horizontal transmission of HBV to adult members of households has also been reported, including in families of children adopted from overseas.32–34

Sexual transmission of HBV is most common among persons at increased risk for other sexually transmitted infections, including those with many sexual partners or a history of other sexually transmitted infections. Sexual intercourse with a known infected person puts one at risk and engaging in certain sexual practices, such as anal intercourse, may facilitate transmission of HBV.35 Men who have sex with men are at particularly high risk for HBV infection, with up to 60% having serologic markers of past or current infection.35,36

Percutaneous and permucosal transmission of HBV can result from transfusion of unscreened blood, injection drug use, occupational exposure (e.g. needle stick injuries) and nosocomial exposures (e.g. unsafe injection and other unsafe medical practices). In the United States, blood transfusion has not been an important mode of transmission since the institution of routine screening for markers of HBV in the early 1970s. However, blood transfusion remains an important source of infection in many less developed countries.

In recent years, unsafe injection and other unsafe medical practices have become increasingly recognized as major routes of HBV transmission, particularly in developing and transitional countries.37 Unsafe injections, which account for an estimated 32% of new HBV infections annually,38 are a consequence of both the reuse of injection equipment without proper sterilization and the overuse of injections where oral therapy would be indicated. The burden of disease from other unsafe medical practices is not known. Nosocomial transmission of HBV is not limited to less developed countries. In the United States and other developed countries, transmission of HBV in healthcare settings – both inpatient and outpatient – continues to occur.39–42 Traditional healing practices that involve breaches in the skin barrier, such as piercing and scarification, have also been documented to transmit HBV. These practices may continue once immigrants and refugees have migrated to a host country.30

In healthcare settings, most transmission of HBV occurs from patient to patient, although transmission from patient to provider and provider to patient also occurs. Before widespread vaccination of healthcare workers, the prevalence of HBV infection in this group was three- to fivefold higher than that of the general US population.43 Currently, an estimated 75% of healthcare workers in the United States are vaccinated.44

Illicit injection drug use is another common mode of transmission among adults worldwide and accounts for a substantial fraction of HBV infections in developing and transitional countries, including, or especially in, the countries of the former Soviet Union.45–47 Drug users often share injection equipment, including needles and syringes as well as other paraphernalia such as cotton and cookers. This sharing, together with the stability of HBV outside the body, provides an easy route for the transmission of the virus. In the United States, approximately 64% of injection drug users have been infected with HBV.48

Global patterns of HBV transmission

In highly endemic countries, the patterns of HBV transmission are very different from those seen in developed, low endemicity countries (Table 22.2). In particular, perinatal and early childhood transmission play key roles, both because they are common and because infections acquired early in life frequently lead to chronic infection (see below). Because most (>60–70%) residents of highly endemic countries are exposed to HBV during childhood, transmission during adulthood is relatively less important.

Table 22.2 Differences in the epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection by endemicity

| Endemicity | Most common age at infection | Most common modes of transmission |

|---|---|---|

| High | ||

| Intermediate | All age groups | |

| Low |

Epidemiology in the United States

Before the introduction of hepatitis B vaccination, there were approximately 300 000 new HBV infections annually in the United States, including 24 000 among infants and children.49 Beginning in the 1980s, the United States adopted a series of measures designed primarily to prevent chronic HBV infection and its long-term complications, cirrhosis and liver cancer. Since 1990, the incidence of hepatitis B has decreased by 90% among children and 63% among adults.50

The success of the US hepatitis B immunization program has highlighted the importance of hepatitis B prevention among immigrants. In a 2001–2002 study of US cases among children born after 1990, 8 of 19 cases were among children born outside of the United States. Many of these children were international adoptees.51

Epidemiologic features of immigrants and refugees in the United States

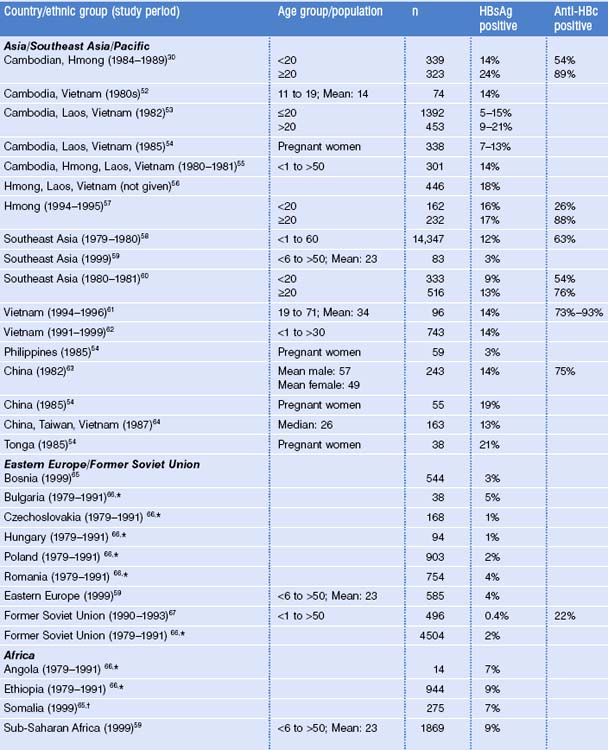

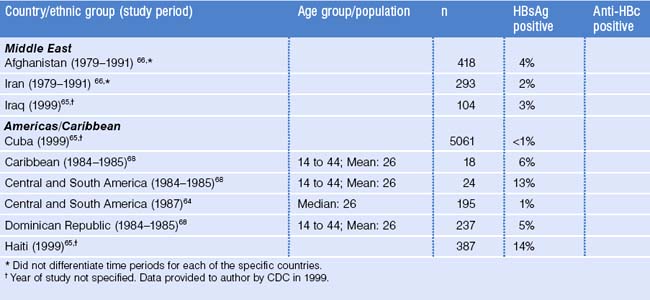

Most immigrants, refugees, and international adoptees come from countries of high and intermediate HBV endemicity where the prevalence of HBV infection is substantially higher than in the United States (see Fig. 22.1). Surveys among these migrant populations have generally shown HBsAg prevalence rates similar to those of their region of origin (Table 22.3).30,52–68 However, among their US-born children, even before the widespread use of hepatitis B vaccine, HBsAg prevalence was substantially lower.69,70

The prevalence of chronic HBV infection varies by region and country of origin, with the highest prevalence among persons coming from East Asia, Southeast Asia and the Pacific (12–18% in most studies; see Table 22.3). The prevalence of anti-HBc among adults in these populations ranges 63–93%. The prevalences of HBsAg and anti-HBc among children and adolescents shown in Table 22.3, which are generally lower than among adults, do not reflect the impact of hepatitis B immunization, as few of the countries had implemented immunization before 2000.

In a population-based study in a community in Minnesota with a large immigrant population, the prevalence of chronic HBV infection was 2.1% among Asians, 1.9% among Africans, and 0.02% among Caucasians. The overwhelming majority (99%) of Asians were immigrants, mainly from Vietnam, Cambodia, China, and Laos; 91% of Africans were immigrants from Somalia.71

Chronic HBV infection is one of the most important causes of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Globally, HCC accounts for an estimated 6% of all cancer deaths, with the highest incidence in countries of high HBV endemicity, especially in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.72 In the United States, HCC mortality is highest among persons of Asian race/ethnicity, followed by Blacks and Hispanics.73 It is lowest among whites. Although whites have the lowest age-adjusted incidence rates, they account for the largest proportion of the US population and thus they account for largest number of HCC cases.

In a study of cases of newly diagnosed liver cancer conducted in California, Hawaii, and Washington using data from a national cancer registry, the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program, the incidence of HCC was substantially higher among Asians (from China, Japan, Philippines) compared to whites. HCC incidence was also higher among foreign-born Asians compared to Asians born in the United States.74

Clinical Manifestations

The characteristic age dependency of clinical outcomes from acute HBV infection75,76 is probably at least partly due to age-dependent differences in the robustness of this immune response. In general, the younger the person at the time of infection, the less likely the person is to have symptoms of acute hepatitis and the more likely he or she is to develop chronic infection. Children infected at birth through perinatal transmission rarely develop signs of acute hepatitis but almost always (>90%) proceed to chronic infection. Children aged 1–5 years occasionally develop signs of acute hepatitis but have a lower risk (25–50%) of developing chronic infection. Adults more commonly develop acute hepatitis and are even less likely (less than 5–10%) to progress to chronic infection.

Acute hepatitis B presents after an incubation period of 6 weeks to 6 months, generally lasts 1–2 weeks, and is followed by a prolonged convalescent period that may last for weeks or months. Symptoms during the acute phase are clinically indistinguish able from those of other acute viral hepatitides and include fever, jaundice, dark urine, fatigue, and abdominal pain. Malaise and anorexia commonly precede jaundice by a few days. Fulminant hepatitis B occurs in less than 1% of cases and is frequently fatal if liver transplantation is not possible.

Chronic HBV infection is defined as the continued presence of HBsAg 6 months after acute illness or HBsAg in the absence of any clinical or serologic evidence of acute hepatitis B. Risk factors for progression to chronic infection, in addition to infection at a young age, include immunosuppression, and chronic, underlying illness.77 Chronic hepatitis B is generally asymptomatic, although circulating immune complexes occasionally result in extrahepatic manifestations such as membranous or membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis or polyarteritis nodosa.

Natural History of Chronic Hepatitis B

The greatest burden of disease attributable to hepatitis B is from the long-term complications of chronic infection, cirrhosis and HCC, which typically occur years to decades after the initial infection. The persistent, low-level hepatitis that occurs in persons with chronic hepatitis B results in a slowly progressive fibrosis of the liver.78 The rate of progression of this fibrosis varies largely from individual to individual and is greater in those with additional risk factors for fibrosis such as alcohol use or coinfection with hepatitis C virus or hepatitis D virus. The end stage of fibrosis is hepatic cirrhosis. Cirrhosis is initially asymptomatic in many patients or may be associated with mild, non-specific symptoms such as fatigue. However, each year about 5% of persons with HBV-related cirrhosis will develop decompensated cirrhosis, with classic manifestations of cirrhosis such as ascites, esophageal varices, and encephalopathy.79 Decompensated cirrhosis carries a poor prognosis, with high 5-year mortality rates.

HCC is the fourth leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide, and in countries where hepatitis B is highly endemic, liver cancer is generally the most common cause of cancer death or the second most common cause after lung cancer.80 In a classic study of chronically HBV-infected Taiwanese civil servants, most of whom had probably been infected in infancy or childhood, the incidence of HCC ranged from 2 per 1000 per year among men in their 30s to almost 10 per 1000 among men in their 60s.81 Using the estimates from this study, 20% of men with chronic hepatitis B could expect to develop liver cancer before the age of 70 years. The incidence of liver cancer among women with chronic hepatitis B is approximately half that among men.82 In addition to male sex, other risk factors for HCC among persons with chronic hepatitis B include alcohol use, cigarette smoking, and the presence of HBeAg, which is associated with a sixfold increase in risk.83

Serologic Diagnosis

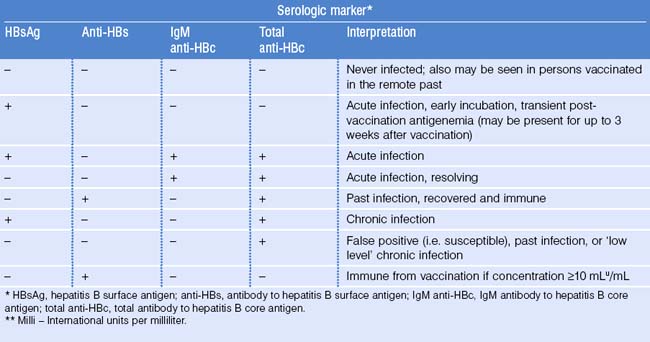

Acute infection

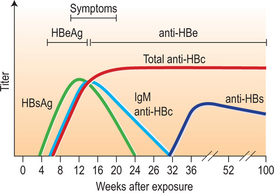

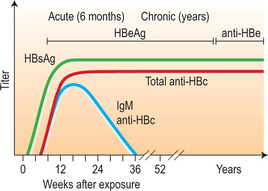

After infection, the first detectable serologic markers are HBsAg and antibody of the IgM subclass to hepatitis B core antigen (IgM anti-HBc). Both appear within 1–2 months after infection and are present at symptom onset (Fig. 22.2; Table 22.4). IgM anti-HBc is diagnostic of acute HBV infection. There are no commercially available tests for HBcAg; thus, this marker is not included in diagnostic algorithms. HBeAg is also detectable in acute infection and its presence is associated with viral replication and high viral load.

Resolution of acute infection

During resolution of infection (see Fig. 22.2), IgM anti-HBc is replaced by antibody of the IgG subclass (IgG anti-HBc). Around the same time, there is clearance of HBsAg followed by the appearance of antibody to HBsAg (anti-HBs), a protective, neutralizing antibody whose presence indicates recovery from acute infection and immunity from reinfection. There may be a brief ‘window period’ between the clearance of HBsAg and the appearance of anti-HBs during which neither HBsAg nor anti-HBs is detectable. IgM anti-HBc may be the only serologic marker present during this time. During resolution, there is also loss of HBeAg and the appearance of anti-HBe. In persons with resolved HBV infection, IgG anti-HBc usually remains detectable throughout life but anti-HBs may become undetectable after many years.

Chronic infection

In chronic infection, HBsAg persists for > 6 months and anti-HBs does not develop (Fig. 22.3; also see Table 22.4). As with acute infection with resolution, IgM anti-HBc disappears and is replaced by IgG anti-HBc. HBeAg, when present in chronic infection, indicates viral replication, high viral titers, increased infectivity, and higher probability of progression to HCC.83 Conversely, the absence of HBeAg and presence of anti-HBe correlates with a lower viral load.

Perinatal infection

Because HBsAg does not cross the placenta, the presence of HBsAg in the serum of an infant is diagnostic of perinatal HBV infection. Both IgG anti-HBc and anti-HBs cross the placenta and thus neither is a useful diagnostic marker of infection in young infants. Passively acquired maternal anti-HBc antibody usually disappears within the first 1–2 years of an infant’s life.84–87

Special serologic patterns

Isolated anti-HBs:

The presence of anti-HBs, with no other serologic marker of infection, is seen after hepatitis B vaccination (see Table 22.4).

Isolated HBsAg:

The presence of HBsAg alone, with no other markers of infection, may be seen very early in infection, before the development of IgM anti-HBc, or immediately after hepatitis B vaccination (see Table 22.4). This transient presence of HBsAg within the first 3 weeks after vaccination has been documented in infants, adolescents, and adults.88–90

Isolated anti-HBc:

Detection of anti-HBc without any other marker of infection, may occur in three situations: (1) false-positive result; (2) remote, past infection with the loss of detectable levels of anti-HBs; and (3) chronic infection in which HBsAg level is below level of detection of commercial assays. In this latter situation, person-to-person transmission of HBV rarely, if ever, occurs.91

Prevention of Hepatitis B

Vaccination schedule

Hepatitis B vaccines are typically given as a three-dose series and there are a variety of vaccination schedules. In the most common schedule in the United States, the second and third doses of vaccine are administered 1–2 months and 6–12 months after the first dose (i.e. 0, 1–2, 6–12 month schedule, Table 22.5).92 For routine infant immunization, the first dose of vaccine should be administered within the first 24 hours after birth and the third dose should be given after 6 months of age.92 Other schedules, including a two-dose series for adolescents 11–15 years old93 and a four-dose series, are also approved for use in the United States.92

Table 22.5 Hepatitis B vaccination schedule for children, adolescents, and adults

| Age | Schedule |

|---|---|

| Children (1–10 years)* | 0, 1, 6 months† |

| 0, 2, 4 months† | |

| 0, 1, 2, 12 months†¶ | |

| Adolescents (11–19 years)* | 0, 1, 6 months† |

| 0, 1, 4 months† | |

| 0, 2, 4 months† | |

| 0, 12, 24 months† | |

| 0, 4–6 months§ | |

| 0, 1, 2, 12 months†¶ | |

| Adults (≥20 years)* | 0, 1, 6 months**†† |

| 0, 1, 4 months** | |

| 0, 2, 4 months** | |

| 0, 1, 2, 12 months¶ ** |

* Children, adolescents, and adults may be vaccinated according to any of the schedules indicated, except as noted. Selection of a schedule should consider the need to optimize compliance with vaccination.

† Pediatric/adolescent formulation.

§ A two-dose schedule of Recombivax-HB adult formulation (10 μg) is licensed for adolescents aged 11–15 years. When scheduled to receive the second dose, adolescents aged > 15 years should be switched to a three-dose series, with doses 2 and 3 consisting of the pediatric formulation administered on an appropriate schedule.

¶ A four-dose schedule of Engerix B is licensed for all age groups.

†† Twinrix may be administered to persons aged ≥18 years at 0, 1, and 6 months.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree