| Test | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Noninvasive tests | |||

| Serology | |||

| Laboratory, serum, ELISA | 86–95 | 78–95 | $$ |

| In-office, serum | 88–94 | 74–88 | $ |

| In-office, whole blood | 67–88 | 75–91 | $ |

| Urea breath test | |||

| 13C-urea breath testa | 90–96 | 88–98 | $$$ |

| 14C-urea breath testb | 90–95 | 90–95 | $$ |

| Stool antigen test | 83–98 | 81–100 | $$ |

| Invasive tests | |||

| Rapid urease test | 88–95 | 93–100 | $ |

| Histology | 93–98 | 95–99 | $$$ |

| Culture | 77–98 | 100 | $$$ |

The method of choice clinically depends on availability, cost, and whether endoscopy is otherwise indicated. Because the diagnosis of an active H. pylori infection should always be followed by eradication therapy, the primary consideration for testing is the willingness to treat the infection. Currently, testing for H. pylori infection is indicated in patients with a wide variety of conditions, including active peptic ulcer disease, a past history of documented peptic ulcer, non-ulcer dyspepsia, gastric MALToma, and adenocarcinoma (Table 138.2).

| Duodenal or gastric ulcer (present or history of) |

| Evaluate success of eradication therapy |

| Gastric low-grade MALT lymphoma |

| Atrophic gastritis |

| After endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer |

| Uninvestigated dyspepsia |

| Non-ulcer dyspepsia |

| Chronic NSAID/aspirin therapyb |

| Chronic antisecretory drug therapy (e.g., Gastroesophageal reflux disease)c |

| Relatives of gastric cancer patients |

| Relatives of patients with duodenal ulcer |

| Relatives of patients with H. pylori infection |

| Patient desires to be tested |

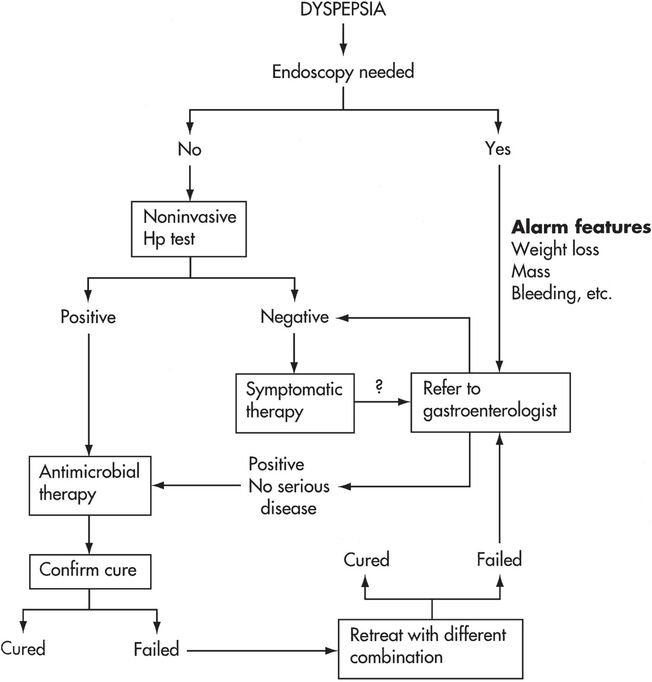

According to guidelines of the European H. pylori Study Group, testing is recommended in dyspeptic patients without alarm symptoms or under 45 years of age, at low risk of malignancy as part of a “test and treat strategy” (Figure 138.1). Noninvasive testing (e.g., the urea breath or stool antigen test) is preferred. Stool antigen tests using monoclonal antibodies are superior to ones using polyclonal antibodies. Serologic testing is often the least expensive test. However, the sensitivity and specificity of serologic tests, particularly in-the-office tests, is typically lower than that of the urea breath test or stool antigen test. Nonetheless, IgG serologic testing remains useful in conditions of high or low pretest probability. For example, a positive test in a patient with a known high probability condition such as a peptic ulcer disease would be considered reliable as would a negative test in a low H. pylori prevalence region in a patient with a low-probability condition such as gastroesophageal reflux disease. In contrast, when one obtains an unexpected result (e.g., a negative serologic test in a patient with duodenal ulcer disease), it would be prudent to retest using a test for active infection. Because antibody titers fall slowly they cannot be relied upon to assess post-eradication status of H. pylori infection. IgA and IgM H. pylori serologic tests are typically inaccurate and not recommended.

Figure 138.1 This algorithm shows one approach to the evaluation of patients presenting with dyspepsia. It has become apparent that in the United States where the incidence of gastric cancer is very low, noninvasive testing with serology, urea breath testing, or fecal antigen testing is sufficient and that endoscopy can be reserved for those with alarm symptoms. Referral to a gastroenterologist should be considered for those with alarm symptoms, those who have failure of symptoms to resolve after successful therapy, and those who fail one or more courses of therapy. The exception is those with clear-cut gastroesophageal reflux disease whose symptoms are not anticipated to resolve after successful cure of H. pylori. Those over the age of 50 with a long history of symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux would be one group where referral should be considered to exclude Barrett’s esophagus.

When endoscopy is clinically indicated, the test of choice is a rapid biopsy urease test using preferably two specimens, one from the antrum and one from the corpus. Biopsy urease testing provides both a high sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of H. pylori infection. If a biopsy urease test is negative, absence of an H. pylori infection should be confirmed by histology. Histology has the advantages of providing a permanent record and allowing identification of the pattern and severity of gastritis. Prospective studies have consistently shown that hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of gastric mucosal biopsies has poor sensitivity and specificity for diagnosis of active H. pylori infections, and a special stain such as immunohistochemistry, the Genta or El-Zimaity triple stains, or the combination of H&E and the Diff-Quik stains should be requested. Culturing H. pylori

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree