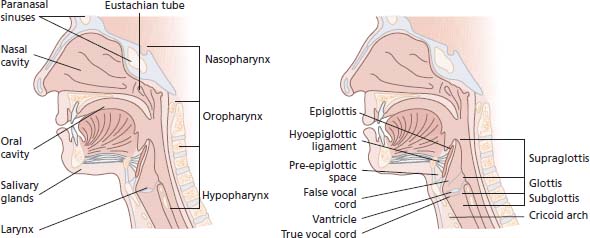

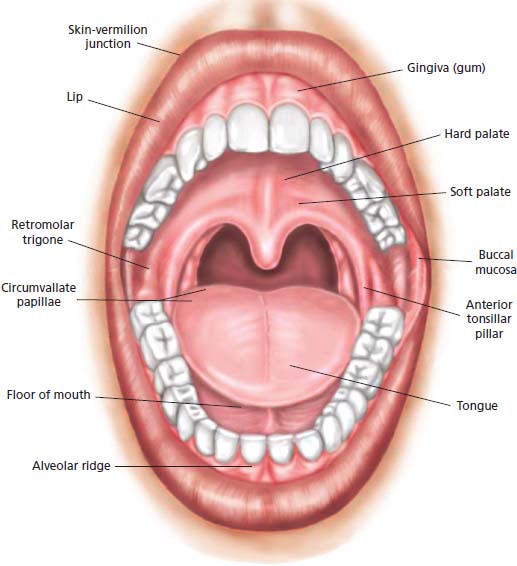

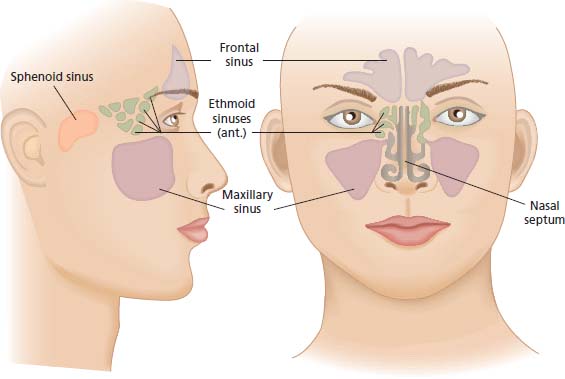

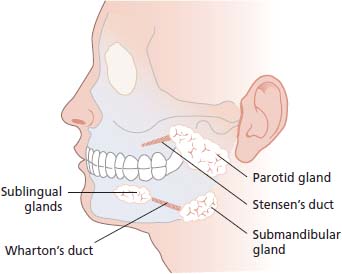

20 There have been advances in our understanding of the causes of head and neck cancers and changes in the standard of care that have come from developments in molecular biology that have been applied to this diverse tumour group. Students who are worried about biodiversity or just simply fans of the Looney Tunes cartoon character Taz may be concerned to learn that the carnivorous marsupial, the Tasmanian devil, has become an endangered species because of a head and neck tumour that threatens the survival of the whole species. Devil facial tumour disease is a parasitic tumour allograft transmitted between individual devils. The tumours are all derived from the same original cancerous cells and spread from animal to animal. Transmissible cancer is extremely rare. The only other well-described example is canine transmissible venereal tumour in dogs, where again it is the actual cancer cells themselves that are spread from dog to dog rather than transmission of an infection that causes the cancer. Occasional similar cancer transmission has been described in humans. For example, organ transplant recipients very rarely develop cancers that are shown genetically to derive from the donor. Transplacental transmission of malignancy has also been described with the spread of melanoma from mother to child. It was announced in 2010 that the actor Michael Douglas had been diagnosed with throat cancer (which subsequently turned out to be base of tongue cancer). In an interview with the Guardian newspaper in 2013, the actor attributed the cancer to human papillomavirus (HPV) infection acquired by cunnilingus. Around 40% of cases of head and neck cancer are associated with high-risk genotypes of HPV, and it has been shown that people with a higher number of sexual partners, particularly oral sex partners, are at an increased risk for oropharyngeal, tonsil and base of tongue cancers. Of course drinking and smoking also contribute. It is intriguing that the actor who portrayed Gordon Gekko in Wall Street turns out to be a political activist advocating nuclear disarmament and gun control and is a UN messenger of peace. Sigmund Freud succumbed to cancer of the head and neck in 1939, but in his case it was attributed to smoking rather than sex. To the oncologist, the head and neck means anything between the brain and the clavicles, excluding the thyroid gland and the skin. It comprises seven regions (Figures 20.1, 20.2, 20.3 and 20.4): Figure 20.1 The anatomy of head and neck cancers. Figure 20.2 The anatomy of the oral cavity. Figure 20.3 The anatomy of the paranasal sinuses. The International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) is the full list of diseases recognized by the WHO and is currently in its 10th revision (ICD-10). Cancers of the head and neck include more than 30 different ICD-10 codes. Although lymphomas, sarcomas, melanomas and other tumours may affect these regions, the term “head and neck cancers” generally refer to squamous tumours, which make up 90% of cancers at these sites. Cancers of the nasopharynx include not only squamous cancers but also non-keratinizing transitional cell cancers and undifferentiated lymphoepitheliomas. The latter are the most common tumours in the nasopharynx, and, unlike most other head and neck cancers, they frequently spread to distant sites. Tumours of the salivary glands are the most heterogeneous group of tumours of any tissue in the body, with almost 40 histological subtypes of salivary gland tumours. Salivary gland tumours are more often benign than malignant. Figure 20.4 The anatomy of the major salivary glands. Table 20.1 Frequency and survival in head and neck cancer by primary tumour site Head and neck cancers comprise 5% of all cancers in the United Kingdom and account for 2.5% of cancer deaths (Table 20.1). They are twice as common in men as in women and generally occur in those over 50 years of age. Over 90% are squamous carcinomas. The incidence of head and neck cancers varies geographically, as does the most common anatomical site of these cancers. Smoking, high alcohol intake and poor oral hygiene are well-established risk factors for the development of head and neck tumours. In addition, the Epstein–Barr virus is implicated in the aetiology of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in southern China, betel nut chewing in oral cancer in Asia and wood dust inhalation by furniture makers, who may contract nasal cavity adenocarcinomas. In the United Kingdom, the incidence and mortality are greater in deprived populations, most notably for carcinoma of the tongue. Primary prevention by smoking cessation and alcohol abstention are the most effective methods of reducing the risk of head and neck cancers. Increasing awareness of head and neck cancers may encourage earlier referral and diagnosis at a stage when the cancer is still curable. In this respect, dentists play an important role in examining the oral mucosa. Retinoids may reduce the risk of both recurrence and second primary tumours in patients following primary therapy. Moreover, they may reduce malignant transformation in precancerous conditions such as leukoplakia. Cancer of the head and neck is often preventable, and, if diagnosed early, is usually curable. Patients, however, frequently have advanced disease at the time of diagnosis. This is incurable or requires aggressive treatment, which leaves them functionally disabled. The optimum management of these tumours requires a multidisciplinary approach, including oncologists, otorhinolaryngologists, oromaxillofacial surgeons and plastic surgeons, along with clinical nurse specialists, speech and language therapists, dieticians and prosthetics technicians. Most head and neck tumours present as malignant ulcers with raised indurated edges on a surface mucosa. Oral tumours present as non-healing ulcers with ipsilateral otalgia (earache). Oropharyngeal tumours present with dysphagia (difficulty swallowing), pain and otalgia. Hypopharyngeal tumours present with dysphagia, odynophagia (painful swallowing), referred otalgia and neck nodes. Laryngeal cancers present with persistent hoarseness, pain, otalgia, dyspnoea and stridor. Nasopharyngeal cancers present with a bloody nasal discharge, nasal obstruction, conductive deafness, atypical facial pain, diplopia, hoarseness and Horner’s syndrome. Nasal and sinus tumours present with a bloody discharge or obstruction. Salivary gland tumours present as painless swellings or facial nerve palsies. Cervical lymph node enlargement as the presenting feature is not uncommon, particularly when the primary tumour lies in certain hidden sites, such as the base of the tongue, supraglottis and nasopharynx. Systemic metastases are uncommon at presentation (10%). Synchronous or metachronous tumours of the upper aerodigestive tract occur in 10–15% of patients. A number of criteria for urgent referral have been established (Table 20.2). Diagnostic surgical resection of cervical nodes, without first determining the site of the primary tumour, may compromise subsequent therapy, increases the morbidity and worsens the outcome. Before biopsying an upper cervical lymph node, nasendoscopy and laryngoscopy and clinical examination should be performed to identify a primary tumour site. For lower cervical and supraclavicular lymph nodes, panendoscopy (laryngoscopy, bronchoscopy, oesophagoscopy) may be required. Table 20.2 Indications for urgent referral for suspected head and neck cancer The approach to managing these tumours varies according to their site, but in general the primary site and potential for cervical lymph node metastases should be considered. Small early-stage tumours, where there are no regional lymph node metastases, should be treated with surgery or radiotherapy, with 60–69% cure rates. The decision between surgery and radiotherapy is often determined by the anatomical site and the long-term morbidity. Function is generally better after radiotherapy but requires daily attendance for 4–6 weeks, whilst surgical treatment is quicker, but patients need to be fit for anaesthesia (see Figure 3.9). Conventional radiotherapy is delivered by photons or occasionally electron beams (β-radiation) for superficial tumours. However, particle beam radiotherapy uses hadrons (colour charge neutral collections of quarks bound by the strong nuclear force) usually protons, neutrons or positive ions. Proton beam therapy is the most commonly used of these techniques but is only available in one institution in the United Kingdom currently. The theoretical advantage of proton beam radiotherapy is that the higher mass of protons results in less scatter and a more concentrated delivery of energy to the tumour and greater sparing of normal adjacent tissues. Proton beam therapy offers promise in the management of head and neck cancers as well as other tumours located in anatomically challenging sites such as intraocular melanoma and retinoblastoma. In recent times it has been suggested that antiprotons (a fermion formed of two anti-up quarks and one anti-down quark) and pi-mesons (formed of an up and an anti-down quark) could be used as particle beam radiotherapy (Box 3.2). More advanced tumours are usually managed surgically, provided that the tumour is resectable. This is followed by adjuvant radiotherapy if the margins are insufficient, or if there is extranodal spread, multiple lymph node involvement or poorly differentiated histology. The resection of large tumours may leave sizeable defects, requiring myocutaneous flaps. Inoperable or recurrent disease may be treated with combinations of chemotherapy and radiotherapy, but outcomes generally remain poor, and in many cases of advanced disease symptomatic palliation is a more valued approach. If cervical lymph node metastases are present, surgical resection is recommended, and, recently, more limited and selective neck dissection has been advocated. This preserves function, especially in relation to the accessory nerve, which, if sacrificed, usually gives rise to a stiff and painful shoulder. A scoring index can be used to predict the likelihood of metastasis to cervical lymph nodes. If the expected incidence of lymph node involvement exceeds 20%, neck dissection is usually recommended. The addition of chemotherapy to radiotherapy, the use of hyperfractionated radiotherapy as well as intensity-modulated radiotherapy have all improved the delivery of radiotherapy for patients with advanced head and neck tumours, resulting in modest improvements in survival and declines in morbidity. The addition of the monoclonal antibody cetuximab, which targets epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), to radiotherapy has been shown to double survival in advanced head and neck cancers, especially tumours of the oropharynx. However, this widely quoted landmark phase III trial did not use cisplatin chemoradiotherapy, the gold standard therapy, as the control arm. Recurrent or metastatic tumour may be palliated with further surgery or radiotherapy to aid local control, and systemic chemotherapy has a response rate of around 30%. The addition of cetuximab to platinum-containing regimens is superior to platinum-containing chemotherapy alone in patients with recurrent disease. Other treatments targeting receptors that have shown promise in these tumours include afatinib, an irreversible ErB blocker, and gefitinib, the EGFR inhibitor. Second malignancies are frequent in patients who have been successfully treated for head and neck tumours, with an annual rate of 3%, and all patients should be encouraged to give up smoking and drinking to lower this risk. In addition, a number of studies have addressed the role of retinoids and β-carotene as secondary prophylaxis, but none have proved to have any significant effect. Quality of life issues are especially important in head and neck cancers, given the anatomical site of the disease and the consequences of treatment, which can affect facial appearance, speech, swallowing and breathing. These cancers have enormous sociopsychological impact and may result in physical disability. These concerns must be addressed sympathetically with patients. Rehabilitation following treatment for head and neck cancers needs input from many professionals, particularly speech and language therapists, dieticians and prosthetics technicians. Rehabilitation, furthermore, requires enormous patience and effort on behalf of the patient. For example, 40% of patients will achieve communication by oesophageal speech following total laryngectomy. Five-year survival rates for patients with head and neck tumours are listed in Table 20.1. Salivary gland tumours represent around 5% of all head and neck cancers and affect both genders equally. They are most common in the sixth and seventh decades of life. Over half of the tumours are benign, and 80% originate in the parotid gland. Approximately 25% of parotid tumours, 40% of submandibular tumours and over 90% of sublingual gland tumours are malignant. Histologically, the most common benign tumour is the pleomorphic adenoma, and the most common malignant tumour is the mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Most patients present with painless swelling of the parotid, submandibular or sublingual glands. Facial numbness or weakness due to cranial nerve involvement usually indicates malignancy and is an ominous sign. Pleomorphic adenomas, although not malignant, often recur if not completely excised, and a small proportion may become malignant if left untreated. Early-stage, low-grade malignant salivary gland tumours are usually curable by surgical resection alone. The prognosis is best for parotid tumours, then submandibular tumours; the least favourable sites are the sublingual and minor salivary glands. Larger or high-grade tumours require postoperative radiotherapy. Complications of surgical treatment for parotid neoplasms include facial nerve palsy and Frey’s syndrome. Frey’s syndrome is gustatory flushing and sweating of the ipsilateral forehead because the sympathetic nerve fibres to the sweat glands of the scalp and parasympathetic fibres to the parotid gland have reconnected wrongly after the auriculotemporal branch of the trigeminal nerve was severed in surgery; instead of salivating the patient sweats. Case Study: The priest with bad breath.

Head and neck cancers

Sites

Proportion of head and neck cancers

5-year survival

Nasopharynx

Nasal cavity

2%

50%

Oral cavity

Buccal mucosa Retromolar triangle Alveolus Hard palate Anterior  tongue Floor of mouth Mucosal surface of lips

tongue Floor of mouth Mucosal surface of lips

40%

50%

Oropharynx

Base of tongue Tonsil Soft palate

25%

45%

Hypopharynx

Postcricoid area Pyriform sinus Posterior pharyngeal wall

20%

Larynx

Supraglottis Glottis Subglottis

30%

95%

Paranasal sinuses

Maxillary sinus Ethmoidal sinus

1%

50%

Salivary glands

Parotid glands Submandibular glands Sublingual glands Minor salivary glands

5%

80%

Epidemiology

Pathogenesis

Clinical presentation

Hoarseness persisting for >6 weeks

Ulceration of oral mucosa persisting for >3 weeks

Oral swellings persisting for >3 weeks

All red or red-and-white patches on the oral mucosa

Dysphagia persisting for >3 weeks

Unilateral nasal obstruction, particularly when associated with purulent discharge

Unexplained tooth mobility, not associated with periodontal disease

Unresolved neck masses for >3 weeks

Cranial neuropathies

Orbital masses

Treatment

Prognosis

Salivary gland tumours

ONLINE RESOURCE

ONLINE RESOURCE

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree