GERM-CELL TUMORS

Part of “CHAPTER 122 – TESTICULAR TUMORS“

ETIOLOGY AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

The etiology of testicular germ-cell cancer is unclear, although genetic, hormonal, and environmental factors seem important.1a For example, the morbidity of testicular cancer in Finland, which has an ethnic background different from that of other Nordic countries, is far lower than in Denmark,2 although the economic, social, and cultural conditions are rather similar. Likewise, the morbidity of testicular cancer is many times less among blacks in both the United States and Africa than in the white population in the United States.2 Familial testicular cancer occurs rarely.3,4

It appears from several lines of evidence that endocrine factors play a role in the development of testicular cancer.5,6,7 and 8 First, germ-cell cancer is extremely rare during childhood except for the first 1 to 2 years after birth. Similarly, blood levels of gonadotropins and sex steroids are extremely low during childhood except for the perinatal period through the first half-year. The increase in the production of follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, and testosterone during puberty is followed by an increase in the incidence of testicular cancer, which peaks 10 to 20 years later.2 Second, germ-cell cancer is extremely rare in patients with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, although this syndrome is associated with a high incidence of cryptorchidism, which generally increases the risk of germ-cell tumors (see later). Third, an association between gonadotropin or clomiphene administration and testicular cancer has been reported occasionally.5,6,7 and 8 Fourth, hCG-producing tumors have a more aggressive course than do other nonseminomas. Fifth, it has been suggested that exogenous estrogens given during pregnancy can lead to testicular cancer of the offspring.9 Nevertheless, the direct role of hormones in the pathogenesis of testicular cancer is unclear.

The average annual age-adjusted testicular cancer incidence rates, which among North American whites and most West Europeans are 3 to 9 per 100,000, have increased two-fold to four-fold during the last few decades.2,10 This increase also has occurred in countries with stable populations; this and other evidence suggest that environmental factors play a role.11

HISTOLOGY: CLASSIFICATION AND DIAGNOSIS

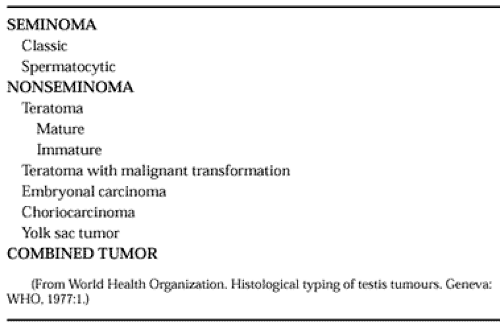

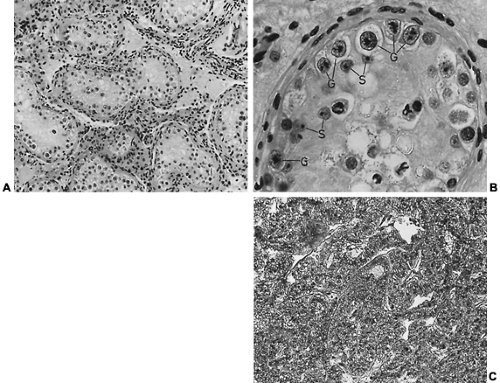

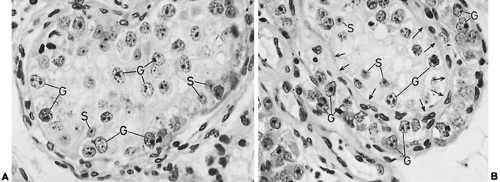

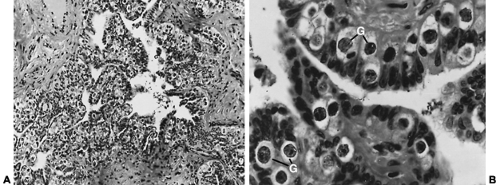

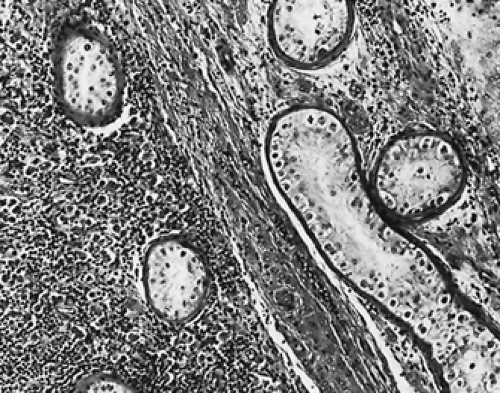

Traditionally, germ-cell tumors are classified as seminomas or nonseminomas12 (Table 122-1; Fig. 122-2, Fig. 122-3, Fig. 122-4 and Fig. 122-5.

Although one type of lesion has been called spermatocytic seminoma,12 there is strong biologic evidence that it is different from seminoma,13,14 so the term spermatocytoma should be used16(also see later).

Although one type of lesion has been called spermatocytic seminoma,12 there is strong biologic evidence that it is different from seminoma,13,14 so the term spermatocytoma should be used16(also see later).

The classic seminoma and the nonseminomatous germ-cell tumors seem to have the same biology. First, several studies have shown that morphologically identical precursor cells, carcinoma in situ (CIS) of the testis, originate both seminomas and nonseminomas15,16 and 17 (see Fig. 122-2 and Fig. 122-5). Second, approximately one-third of germ-cell tumors contain mixed elements of seminomas and nonseminomas.18 Third, the seminoma cells sometimes have functional properties similar to those of choriocarcinoma cells, including hCG production,19,20 and 21 thus indicating that intermediate forms exist. Nevertheless, practically, especially in relation to treatment, it remains appropriate to maintain the distinction between seminomas and nonseminomas.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree