General Principles and Management

Steven S. Chang

Joseph A. Califano

INTRODUCTION

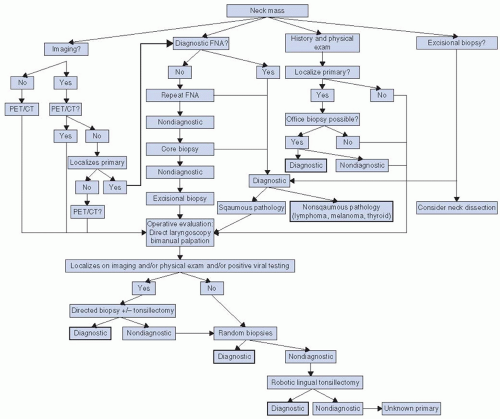

Metastatic cervical carcinoma with an unknown primary (MCCUP) represents a small proportion of all head and neck cancers. As a head and neck surgeon, the primary goal is to utilize the many diagnostic options available to determine the site of the primary. In this chapter, we will describe a thoughtful, evidence-based, and stepwise approach to the workup of the MCCUP to search for the primary tumor. We will also address the role of surgery and radiation in the management of MCCUP. Lastly, we will discuss outcomes of treatment. The various options for workup and treatment will be summarized in an algorithmic form (Fig. 15-1).

DEFINITION

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines carcinoma of unknown primary as the histological diagnosis of metastases without diagnosis of a primary tumor, an entity that constitutes 3% of all malignant neoplasms.1 As a distinct subgroup, MCCUP represents 2% to 9% of all head and neck cancers.2,3,4,5,6

The entity of MCCUP was first described in 1944 by Martin and Morfit7 as metastatic disease in lymph nodes of the neck without any evidence of a primary mucosal lesion. The definition of a neck cancer of unknown primary was carefully outlined in 1957 by Comess et al.8 and further defined by Jesse in 19669 at MD Anderson Cancer Center in a series of 127 patients. In 1973,10 the same group described treatment recommendations that consisted of treatment of the ipsilateral neck along with radiation to potential mucosal sites.

Although the histological subtype of MCCUP is most commonly squamous cell carcinoma (SCC),11 the entity actually includes all patients with unknown primary regardless of histological subtype. Some reports have noted 50% of MCCUP to be SCC and 20% to be undifferentiated.12 Other types of malignancies, such as adenocarcinoma and melanoma rarely occur, but have a different workup, treatment, and prognosis13,14 and therefore are not discussed in this chapter, which is focused on SCC. With that said, there are circumstances in which certain mucoepidermoid tumors (especially tongue) present as adenopathy that cytologically resembles SCC. Although unknown primary SCC of cervical lymph nodes is by far the most common subtype of unknown primary carcinoma seen by head and neck oncologists and is the focus of this chapter, one must remember that this subgroup of patients represents <10% of all unknown primary carcinomas.15,16 The definition of unknown may change depending on the physician and the workup performed. What is unknown to a generalist may in fact be easily discoverable with a thorough head and neck examination, and what was unknown 25 years ago may now be easily discoverable by improved radiologic imaging. In those cases in which the primary tumor is not initially obvious, >50% of lesions are discovered by physical examination, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and/or panendoscopy.17 A paper from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center showed that >50% of patients referred for treatment of unknown primary head and neck cancer had a primary lesion identified within 2 weeks of presentation.7 A similar study from Liverpool reports that 56% of primary lesions were identified by an otolaryngologist—head and neck surgeon in cases originally thought to be of unknown primary site.18

Although other head and neck cancers have increased in incidence over the last 20 years, a Danish survey reports a stable incidence of 0.34 cases/100,000/year of unknown primary cervical carcinoma. It is possible, however, that an increase in the incidence of unknown primary carcinoma has been masked by improvements in detection of the primary lesion.

OVERALL STRATEGY FOR DISCOVERY OF SITE OF PRIMARY ORIGIN

A critical component to management of MCCUP includes the search for the site of an occult primary tumor. The importance of this exercise cannot be overestimated, as different primary sites

have vastly different prognostic factors, staging, and therapeutic options. Failure to accurately define a primary tumor of origin may potentially result in ineffective or inappropriate therapy as well as unwanted treatment morbidity. A high premium, therefore, is placed on discovery of the site of the unknown primary.

have vastly different prognostic factors, staging, and therapeutic options. Failure to accurately define a primary tumor of origin may potentially result in ineffective or inappropriate therapy as well as unwanted treatment morbidity. A high premium, therefore, is placed on discovery of the site of the unknown primary.

NATURAL HISTORY

By definition, in unknown primary cancer, the primary tumor is not evident. If left untreated, however, it becomes evident in 13% to 55% of patients after neck surgery alone.10,19,20,21 When the primary does emerge, it usually enlarges, becomes macroscopic and symptomatic through locoregional progression. The emerging cancer (usually squamous carcinoma) varies in rapidity of growth, but if left untreated usually assumes aggressive locoregional progression. Locoregional control, therefore, is very important in order to achieve acceptable survival.22

Numerous theories attempt to explain the fact that many patients with MCCUP never develop a primary tumor even if the potential primary sites remain untreated. One possible explanation is that the neck mass is the only site of carcinoma and that no primary malignancy ever existed. A third possibility is that spontaneous regression of the primary tumor occurred after the metastatic disease had already become established. A third possibility is that the primary tumor remains viable, but quiescent, and therefore never becomes clinically or radiographically apparent.

The concept that SCC can develop spontaneously in the neck has been a topic of debate in the literature for >100 years. In 1882, Von Volkmann7 proposed the theory that cervical squamous cell cancer can develop from a branchial cleft cyst. This is based upon the fact that branchial cleft cysts may share similar histopathologic features with metastatic SCC. Cytopathology is not always able to clearly distinguish between benign and malignant cystic squamous lesions of the neck, especially when it comes to separating benign lymphoepithelial cysts with reactive squamous atypia from well-differentiated carcinomas.23,24,25 However, the preponderance of evidence argues against this theory as an explanation for cervical lymph node metastasis. One argument against this is that branchial cleft anomalies are

in themselves rare. Because almost all patients with unknown primary SCC present with neck masses of recent onset, a large number of subclinical brachial cleft cysts would have to be present to account for the number of cases of unknown primary SCC. Therefore, on the basis of probability alone, this hypothesis is unlikely. Furthermore, with the advent of P16 and high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) testing to define cystic, cervical nodal metastases from high-risk HPV primary oropharyngeal tumors, this dilemma has largely been resolved.23,24,25

in themselves rare. Because almost all patients with unknown primary SCC present with neck masses of recent onset, a large number of subclinical brachial cleft cysts would have to be present to account for the number of cases of unknown primary SCC. Therefore, on the basis of probability alone, this hypothesis is unlikely. Furthermore, with the advent of P16 and high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) testing to define cystic, cervical nodal metastases from high-risk HPV primary oropharyngeal tumors, this dilemma has largely been resolved.23,24,25

A second possibility that would account for SCC arising solely in the neck would be if epithelial rests present in the neck, either in soft tissue or cervical lymph nodes, underwent malignant degeneration. However, there is no evidence that epithelial rests exist in the soft tissues or lymph nodes of the neck; so this does not seem to be a viable explanation for the presence of MCCUP. Occasionally, the primary tumor spontaneously regresses, presumably because of the body’s natural immune process.26 Possibly, a small primary site has expended itself during the process of metastasis or because of victory of local immune factors over alien neoplasia. Leukoplakia,27,28 which is sometimes a precursor to invasive cancer, has been reported to regress in 37% to 44% of cases and even when dysplasia is present it has been reported to regress in 10%29 of cases. In surgical-only treatment of unknown primary metastasis, most of the time no primary tumor develops.30 Then, one must assume that in some of the cases where no primary tumor develops, the primary tumor has, in fact, regressed. There is also the possibility of local immunity being responsible for local tumor containment. In squamous cell cancer, different tumors possess different genetic mutations accounting for malignant degeneration. It is possible that some tumors possess mutations that allow metastasis rather than uncontrolled growth. If the metastatic disease then undergoes additional metastasis allowing for uncontrolled growth, or if the native environment of the lymph node enables uncontrolled growth of the tumor, patients could present with an undetectable microscopic primary lesion and a large cervical metastasis. Mutations that allowed degradation and migration through the basement membrane could account for such behavior. Despite the significant increase in research that has been performed on the molecular genetics of SCC, no significant data yet exist to support this theory. Although the development of the primary tumor is a major concern in patients with unknown primary cervical squamous cell cancer, the most important prognostic factor for these patients is nodal stage.

STAGING

The staging for MCCUP follows the tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) guidelines established for other sites in the head and neck (Table 15.1). After workup, all patients by definition are classified as TO due to the absence of an obvious primary site and N + due to the presence of nodal metastasis. Nodal staging is assigned as with other sites in the head and neck.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The typical presentation of a patient with MCCUP is a unilateral painless neck mass that has enlarged over recent months. The patients usually present to a primary care physician and usually at the time of diagnosis have received several courses of antibiotics. Persistence of the painless, enlarging mass should then be evaluated by a head and neck surgeon. Studies have demonstrated that the median interval of symptom onset to accurate diagnosis by a head and neck surgeon is 3 months.31 The median age of presentation for these patients is 55 to 65 years, although patients as young as 15 years have been reported.32

TABLE 15.1 AJCC Staging for Metastatic Cervical Carcinoma with an Unknown Primary | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

The first step in the workup of a patient with unknown primary SCC is a thorough office examination with a history and physical examination. Each component of the office examination is essential to directing the operative plan to rule out a primary and determine whether the patient is a true unknown primary and thus dictates the treatment plan.

HISTORY

Many aspects of the history can alter a head and neck’s suspicion for a primary site. Historically, most patients diagnosed with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) were older males with a significant tobacco and alcohol history. However, with the recent epidemic of HPV-related oropharyngeal SCC, there has been an increase in younger patients and a more even distribution among sexes. HPV-related malignancy is often a distinct entity from smoking- and alcohol-related malignancy with a different prognosis. Therefore, it is no longer safe to assume that a young female patient with a neck mass is unlikely to have a malignancy or to assume that she has a significant tobacco or alcohol history and that her prognosis is the same.

The patient’s symptoms, if any, may help identify the primary site. Epistaxis, nasal obstruction, or complaints consistent with otitis media point to a nasopharyngeal primary. Complaints of otalgia, dysphagia, or dysarthria may suggest an oropharyngeal or hypopharyngeal primary lesion. Laryngeal lesions often result in voice and respiratory changes. The time course of the tumor growth can often be helpful in formulating the differential.

A careful medical history can also be very helpful. A history of previous skin cancer or immune suppression can be essential in directing the investigation for the primary. The social history can also be useful, with particular attention to tobacco use, alcohol use, sexual history,33 ethnicity/race, foreign travel, sun exposure, and radiation exposure.

Personal and institutional review of the outside records of any ancillary testing such as imaging and pathology is strongly encouraged to ensure nothing is overlooked. When reviewing the pathology, particular attention should be paid to the histopathology

of the tumor and HPV status. When reviewing radiology, it is important to examine the location of the metastasis and its relationship to surrounding structures. For instance, a poorly differentiated tumor with basaloid features and a large cystic level II lymph node in a young never-smoker female has a high probability of being an HPV-related tumor of the oropharynx.

of the tumor and HPV status. When reviewing radiology, it is important to examine the location of the metastasis and its relationship to surrounding structures. For instance, a poorly differentiated tumor with basaloid features and a large cystic level II lymph node in a young never-smoker female has a high probability of being an HPV-related tumor of the oropharynx.

Regardless of the patient’s symptoms (or lack thereof), a history and physical examination by a head and neck surgeon is essential to the workup.

PHYSICAL EXAM—NECK

Location of Metastasis

A careful examination of the neck metastasis is essential, paying particular attention to its location and relationship to surrounding structures. The most frequent cervical metastatic site in patients with MCCUP is level II, which is the circumstance in >50% of patients.2,31,34,35,36 After level II, level I and level III lymphatics are next most common. Lower neck and supraclavicular metastasis are also common and are more frequently associated with a primary site located below the clavicles.3,24,37 Unilateral nodal involvement is the most common presentation, but bilateral nodes are seen in 10% of cases.12,14,38 If multiple bilateral enlarged nodes are encountered, infection, lymphoma, and nasopharyngeal cancer should be placed higher in the differential diagnosis. Presentation with only a single node occurs in 44% to 52% of patients10,38 and the median nodal size is 5 cm (2-14 cm).12 An isolated nodal mass in the submental triangle is rarely cancer. Typically, these masses are inflammatory or related to benign salivary gland conditions. Posterior palpable nodes in a young patient are usually benign, many resulting from inflammation. By identifying the nodal stations involved and understanding patterns of lymphatic drainage with regard to primary sites, more focused diagnostic procedures and treatment strategies can be developed (Table 15.2). Therefore a thorough understanding of the anatomy of the neck is essential. Below is a description of the levels of the neck with their corresponding sites of drainage.

Level I includes the submental and the submandibular nodes. Level IA drains the floor of the mouth, the anterior tongue, the anterior inferior alveolar ridge, and the lower lip. Level IB drains the oral cavity, the anterior nasal cavity, and the soft tissue of the midface. Level II encompasses the upper internal jugular nodes. Level II nodes most commonly receive drainage from the oral cavity, the nasopharynx, the oropharynx, the larynx, the hypopharynx, and the parotid gland. Level III, which includes the middle jugular nodes, receive drainage from the oral cavity, the nasopharynx, the oropharynx, the larynx, and the hypopharynx. Level IV, which encompass the lower jugular nodes, typically receives drainage from the larynx, the hypopharynx, the thyroid, and the esophagus. Level V covers the entire posterior triangle and drains the nasopharynx, the oropharynx, and the skin of the posterior scalp. Level VI is the main drainage basin for the thyroid, the subglottic larynx, the hypopharynx, and the esophagus. Level VII overlies the tracheal esophageal grooves and the superior mediastinum from the manubrium to the superior edge of the inominate vein. The retropharyngeal nodes are not assigned a level, they drain the nasopharynx, the hypopharynx, and the larynx. The supraclavicular nodes are also not assigned a level, but are considered separately from levels I to VII. They drain from the thoracic duct on the left or the accessory thoracic duct on the right. When these nodes are present without superior neck adenopathy, the diagnostician should search for a primary site in infraclavicular or subdiaphragmatic locations. The location of the lymph nodes can help guide the search for a primary because 63 % of patients with supraclavicular nodal presentation are found to have infraclavicular primaries compared to 5 % of patients with jugular nodal presentation,20 3 % to 8 % of patients with unknown primary SCC to have a lung primary.27,38,39,40 A study by Jones et al.18 showed that infraclavicular primary lesions occurred in 30 of 267 patients (11%), whereas head and neck primary lesions were found in 174 of 267 patients (65%). Eighty-three percent of infraclavicular primary lesions discovered were in the lung. Fifteen of the 25 lung cancers were identified during the initial workup whereas 10 were identified during follow-up or at autopsy. These data are summarized in Table 15.2.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree