Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) is a rare malignancy of mesenchymal origin. The true incidence of GIST has historically been underestimated as these tumors were commonly misclassified as leiomyomas, leiomyosarcomas, and leiomyoblastomas.1 The term gastric stromal tumor was first proposed in 1983 to describe gastric wall tumors that lacked the ultrastructural features of smooth muscle cells and the immunohistochemical characteristics of Schwann cells.2 Mazur and Clark2 examined 28 gastric wall tumors that were originally classified by light microscopy as leiomyomas or leiomyosarcomas and, using electron microscopy, determined that some of these tumors lacked features expected in cells derived from smooth muscle. Additionally, using immunohistochemistry to identify the neuroectoderm marker S-100, they found that the majority of tumors failed to show evidence of a nerve sheath origin. They postulated that this subset of tumors that did not appear from a smooth muscle origin or peripheral nerve origin may arise from the myenteric nervous system.

In the early 1990s, confusion persisted as to the lines of differentiation of these stromal tumors which prevented accurate determination of their biologic behavior. Continued investigation into the immunophenotype demonstrated that some of these stromal tumors showed neural, smooth muscle, bidirectional differentiation, or neither.3 In 1995, Miettinen et al4 discovered that 70% of GISTs were positive for CD34, a myeloid progenitor cell antigen also present in endothelial cells and fibroblasts. This approach was, however, imperfect as no more than 60% to 70% of GISTs are CD34 positive, and Schwann cell neoplasms and some smooth muscle tumors are also CD34 positive.1

It was not until the late 1990s when Hirota et al5 discovered that GISTs express KIT (CD117), a receptor tyrosine kinase encoded by the proto-oncogene c-kit. It was also discovered that interstitial cells of Cajal, which are considered the pacemaker cells of the gastrointestinal tract, were positive for both KIT and CD34 and are the most likely cell of origin of GISTs.5–8 In subsequent studies, the gain-of-function mutation of c-kit that results in ligand-independent tyrosine kinase activity was identified in 85% to 100% of so-called “benign” and “malignant” GISTs but not in gastrointestinal leiomyomas or leiomyosarcomas.6,9

This discovery not only impacted the ability to accurately identify GISTs, but also led to a breakthrough in management. The receptor tyrosine kinase KIT was found to have a similar structure to ABL, a tyrosine kinase implicated in chronic myelogenous leukemia. Imatinib mesylate (Gleevec, Novartis, Basel, Switzerland) is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor that had been shown to be successful in the treatment of chronic myelogenous leukemia and was also found to selectively inhibit KIT. In 2001, a 50-year-old woman with rapidly progressing metastatic GIST was treated with imatinib and within 1 month of treatment had a complete metabolic response by [18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) and a 50% decrease in tumor volume on MRI.10 This remarkable finding subsequently sparked a series of clinical trials that dramatically changed the treatment and ultimately the prognosis of patients with GISTs.

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors are the most common mesenchymal tumors, accounting for 80% of those found in the GI tract and 18% of all sarcomas.11 The true incidence of GISTs has been difficult to determine until discoveries in the molecular biology of GISTs in the late 1990s allowed differentiation from other gastrointestinal mesenchymal tumors. In a study utilizing the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database from the National Cancer Institute, the reported incidence of GIST was 0.028 cases per 100,000 in 1992 and 0.688 cases per 100,000 in 2002, a 25-fold increase likely representing more accurate diagnosis.12 Population studies from Europe have reported the annual incidence of GISTs to be 11.0 to 14.5 per million population.11,13,14 Extrapolating data from previous studies provides an estimated incidence of GISTs in the United States to be between 3000 and 5000 cases per year.15

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors have a slight male predominance and may be more common in African Americans.12,16 While GISTs are known to occur in all age groups, approximately 80% occur in individuals over the age of 50, with a reported median age at diagnosis of 58 to 65 years.11,16–18 Pediatric cases account for 1.4% to 2.6% of all GISTs and have even been reported in a 6-day-old neonate.19–21 In the pediatric population, GISTs most commonly occur during the second decade of life with a median age at diagnosis reported between 13 and 14.5 years.22 In contrast to adult GISTs, pediatrics GISTs are more commonly epithelioid-type (as opposed to spindle cell-type), have a female predominance, tend to be multifocal at presentation, have a higher incidence of lymph node metastases, and lack a KIT or platelet-derived growth factor receptor-α (PDGFRA) mutation.23,24

There are no identified epidemiologic risk factors that have been associated with GISTs. While the majority of GISTs arise sporadically, a small number may occur in the setting of a hereditary syndrome.

Familial GISTs tend to occur at a younger age than sporadic GISTs with a median age at diagnosis of 46 years. These syndromes are typically characterized by multifocal primary tumors associated with a variable clinical phenotype. A number of families with history of multiple members affected by GIST have been described in the literature.25 The first heritable mutation was discovered by Nishida et al26 in 1998. Multiple members of a Japanese family developed both GISTs associated with skin hyperpigmentation. Germline DNA analysis revealed a c-kit exon 11 mutation which resulted in a deletion of a valine residue in the juxtamembrane domain of the KIT protein. Additional reports of families with single base mutations have also been described whose phenotype has included urticarial pigmentosa.27,28 Other mutations involving exon 11 have since been discovered. Familial GISTs have also been found to be associated with mutations in exon 17, which encodes the KIT tyrosine kinase II domain.29 A family with multiple GISTs was found to have a single base mutation resulting in the substitution of valine for aspartic acid-816 which led to constitutive activation of KIT. This family did not have evidence of hyperpigmentation; however, multiple family members expressed a common complaint of dysphagia. Germline mutation in exon 13 has also been associated with a predisposition for familial GIST.30 Substitution of glutamic acid for lysine-642 in the kinase I domain was associated with urticarial pigmentosa but not hyperpigmentation in this family. A mutation involving exon 8 has been described in a family with GISTs and macrocytosis.31 This mutation involves a deletion of codon 419 in the extracellular portion of KIT resulting in constitutive activation of KIT.

Germline PDGFRA mutations are much less common and have been reported to involve exon 12.32,33 The initial discovery was found in a French family with five family members with GISTs who did not have a germline mutation in the KIT coding sequence. Sequencing of PDGFRA exon 12 detected a missense mutation resulting in a tyrosine substitution for a highly conserved aspartic amino acid at codon 846. Interestingly, affected family members displayed a congenital malformation with unusually large hands, a phenotype not previously seen in KIT mutation carriers. Germline mutations in PDGFRA exon 12 have also been associated with GIST in combination with small intestinal polyps, fibroid tumors, and lipomas.33 This phenotype results from a missense mutation caused by an aspartic acid substitution for valine.

Carney–Stratakis syndrome is a dyad of paraganglioma and GISTs that was first described in 12 patients in 2002.34 This is an autosomal dominant syndrome that is characterized by both multifocal paragangliomas and GISTs.35 GISTs associated with this syndrome do not have KIT or PDGFRA mutations but do display inactivating germline mutations of succinate dehydrogenase subunits A (SDHA), B (SDHB), C (SDHC), or D (SDHD).36–38

Carney’s triad is a rare, nonheritable syndrome characterized by the triad of gastric GIST, paraganglioma, and pulmonary chondroma.39 Two additional tumors have since been added to this syndrome, esophageal leiomyoma and adrenal cortical adenoma.40 Compared with sporadic GIST, Carney triad–associated GISTs exhibit a female predilection, younger patient age (mean 22 years), multifocality, and frequent lymph node metastasis.41 These tumors have been shown to lack KIT and PDGFRA germline mutations; however, deletion of 1q12-1q21 chromosomal region, which involves the SDHC gene, and 1p region has been described.35

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) is the most common autosomal dominant inherited disorder, occurring in approximately 1 in 3000 people.42 NF1 is characterized by a spectrum of clinical features including cutaneous neurofibromas, café-au-lait macules, axillary and inguinal freckling, ocular hamartomas, and both benign and malignant tumors of the gastrointestinal tract. In a series of 70 NF1 patients, 5 patients (7%) developed GISTs.43 Additionally, this same study found that at autopsy, GISTs were incidentally discovered in up to one-third of the patients. In contrast to sporadic GISTs, NF1-associated GISTs are frequently multifocal and most commonly involve the small intestine.44 Review of germline mutations in NF1-associated GISTs showed that none had detectable KIT or PDGFRA mutations; however, immunohistochemical stains for KIT protein were positive in the majority of these tumors.44,45

Hirota et al5 first discovered the gain-of-function mutation in KIT in 5 patients with GIST. While 95% of GISTs are immunohistochemically positive for KIT, KIT mutations are found in only 70% to 80% of sporadic GISTs.7 The KIT receptor tyrosine kinase normally binds KIT ligand (stem cell factor) which results in receptor homodimerization, phosphorylation, and cellular proliferation. KIT is normally expressed at high levels in hematopoietic stem cells, mast cells, melanocytic cells, germ cells, and the interstitial cell of Cajal.8 Oncogenic KIT mutations result in ligand-independent kinase activation leading to malignant transformation and unregulated cell growth.5,46,47 As described above, germline KIT mutations have been discovered that vary in their anatomic distribution and response to imatinib.48,49

Mutations in exon 11, which encodes the juxtamembrane domain, are the most common and found in two-third of GISTs.49 These mutations include deletions, insertions, single base substitutions, and various combinations of these.48,50 While KIT exon 11 mutations have been shown to be associated with a higher rate of disease recurrence following complete resection than other KIT oncogenic mutations, a recent analysis of the ACOSOG Z9001 trial by Corless and colleagues49,51 demonstrated that tumor genotype was not an independent predictor of recurrence-free survival (RFS). Deletion mutations in exon 11 are an independent adverse prognostic factor, and deletion mutations have a worse prognosis than those with point mutations.52–54 Deletions specifically involving codon 557 and 558 are considered mutational “hot spots” and are associated with a particularly aggressive, metastatic behavior.55,56

Of the 20% to 30% of GISTs that do not demonstrate a KIT mutation, one-third exhibit a mutation in a related tyrosine kinase, PDGFRA.57 Activating mutations of KIT and PDGFRA are mutually exclusive events in GISTs.57,58 PDGFRA has similar downstream signaling pathways, and mutations result in constitutive kinase activation. PDGFRA mutations most commonly involve exon 18 and have also been demonstrated in exons 12 and 14.49 Substitution of valine (V) for aspartic acid (D) at codon 842 in exon 18 accounts for 70% of all PDGFRA mutations and is associated with imatinib resistance.59 GISTs harboring a PDGFRA exon 18 D842V mutation have been shown to have a gastric location predilection, have a lower risk of recurrence than GISTs with KIT mutations, and generally follow a more indolent course.60

Approximately 10% to 15% of GISTs do not harbor mutations in KIT or PDGFRA and traditionally have been called “wild-type (WT)” GISTs.48 These tumors are clinically indistinguishable from those harboring a KIT or PDGFRA mutation and express high levels of KIT and can occur anywhere in the gastrointestinal tract.7 However, with the progressive discovery of pathologic mutations in the non-KIT, non-PDGFRA mutant GIST, the term “wild-type” is really a misnomer. Recent studies have shown that WT GISTs exhibit a variety of other mutations. One of these is a BRAF V600E substitution, as seen in melanoma, papillary thyroid cancer, and colorectal cancer, that has been identified in 7% to 13% of WT GISTs.61,62 Mutations associated with familial WT GISTs have also been identified, as previously discussed. SDH mutations associated with Carney–Stratakis syndrome have been identified in 12% of WT GISTs.63 WT GISTs have also been associated with NF1, in that 7% of WT GISTs have a germline mutation in the neurofibromin 1 gene.48 Overexpression of insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor has recently been discovered in WT GIST tumors; however, it is unclear how this contributes to GIST pathogenesis but could be a potential therapeutic target.64

The three main histologic subtypes of GIST include spindle cell, epithelioid, and mixed type.6 The spindle cell form is the most common, accounting for 70% of GISTs, while the epithelioid and mixed types are less common, seen in 20% and 10% of GISTs, respectively.1 GISTs of spindle cell form are composed of uniform cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm arranged in intersecting fascicles. The epithelioid type is identified by rounded cells with variable eosinophilic or clear cytoplasm. The pathologic diagnosis relies on both the histologic analysis as well as immunohistochemical analysis. As previously discussed, 95% of GISTs demonstrate KIT immunohistochemical positivity.7 The epithelioid type has weaker KIT positivity than the spindle cell type.65 Other markers of previous interest demonstrated variable positivity, including CD34 (60% to 70%), smooth muscle actin (30% to 40%), and S-100 (5%).15 Discovered on gastrointestinal stromal tumor 1 (DOG1), also known as ANO1, is a monoclonal antibody against a chloride channel protein expressed by GIST tumors. DOG1 antibodies have been shown to have a sensitivity of greater than 95% for GISTs and will identify KIT-negative GISTs harboring PDGFRA mutations.66

The majority of patients diagnosed with a GIST are symptomatic. A large population-based study has shown that approximately 70% are symptomatic at time of diagnosis, 20% are asymptomatic, and the remaining 10% are discovered incidentally at time of autopsy.14 GISTs can occur anywhere along the GI tract; however, they most commonly arise in the stomach (60% to 70%), in addition to the small intestine (20% to 30%), and colon/rectum (10% to 15%).17,67 GISTs most commonly present with GI bleeding, vague abdominal pain, obstructive symptoms, or with a palpable abdominal mass. GISTs are highly vascular, friable tumors and may present with massive gastrointestinal or intraperitoneal hemorrhage.68 Symptomatic GISTs tend to be large with an average size of 6 cm while incidentally found GISTs are typically small with an average size of 2 cm.14

Extragastrointestinal GISTs are rare tumors that have been shown to be histologically and immunophenotypically similar to those GISTs arising in the gastrointestinal tract.69 Extragastrointestinal GISTs account for less than 10% of GISTs and are most commonly intra-abdominal and involve the omentum or mesentery.17 These tumors typically demonstrate a more aggressive behavior than gastric GISTs with a poorer prognosis similar to that seen in small-intestine GISTs.69 There is some debate whether these are truly extragastrointestinal primaries or metastases from as yet unrecognized primary site.70

Up to 50% of patients will present with metastatic disease, with the majority involving the liver.17 Additional intra-abdominal sites include the peritoneum and omentum, while extra-abdominal metastases to the lung, brain, bone, or lymph nodes occur in less than 5% of patients.

The first formal staging system for GIST was implemented by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) in 2010.71 Staging of GISTs is divided into two main prognostic groups based on location: gastric GISTs (also used for omentum) and small-intestine GISTs (also used for esophagus, colorectal, mesentery, and peritoneum) (Table 118-1). This is based on evidence that small intestine GISTs have a greater risk of recurrence and metastases than gastric GISTs.72–74 The TNM classification is combined with the mitotic rate to determine the individual stage based on tumor location. Because of the limited availability of tumor mutation testing, mutational status is not included in the AJCC staging system. This staging system has been validated and proven to be a reliable indicator of prognosis in terms of DFS and overall survival (OS), with tumor size and mitotic index being the most important prognostic factors.75

The American Joint Committee for Cancer (AJCC) TNM Definitions for GISTa

| Primary Tumor Size (T) | ||||

| TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed | |||

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor | |||

| T1 | Tumor ≤2 cm | |||

| T2 | Tumor >2 cm but not > 5 cm | |||

| T3 | Tumor >5 cm but not > 10 cm | |||

| T4 | Tumor >10 cm in greatest dimension | |||

| Regional Lymph Nodes (N) | ||||

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed | |||

| N1 | No regional lymph node metastasis | |||

| N2 | Regional lymph node metastasis | |||

| Distant Metastasis (M) | ||||

| M0 | No distant metastasis | |||

| M1 | Distant metastasis | |||

| Gastric GISTb | ||||

| Stage | T | N | M | Mitotic Ratec |

| IA | T1 or T2 | N0 | M0 | Low |

| IB | T3 | N0 | M0 | Low |

| II | T1 | N0 | M0 | High |

| T2 | N0 | M0 | High | |

| T4 | N0 | M0 | Low | |

| IIIA | T3 | N0 | M0 | High |

| IIIB | T4 | N0 | M0 | High |

| IV | Any T | N1 | M0 | Any rate |

| Any T | Any N | M1 | Any rate | |

| Small Intestine GISTd | ||||

| Stage | T | N | M | Mitotic Rate |

| I | T1 or T2 | N0 | M0 | Low |

| II | T3 | N0 | M0 | Low |

| IIIA | T1 | N0 | M0 | High |

| T4 | N0 | M0 | Low | |

| IIIB | T2 | N0 | M0 | High |

| T3 | N0 | M0 | High | |

| T4 | N0 | M0 | High | |

| IV | Any T | N1 | M0 | Any rate |

The prognosis of GISTs is highly variable and thus has been difficult to clearly define. Tumors that are very small with low mitotic rates have been known to metastasize, making it difficult to confidently label any GIST benign. Multiple risk stratification systems have been developed to aid in determination of prognosis (Table 118-2). In 2001, the first consensus conference was held at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to develop a practical method for risk assessment for GISTs.1 Instead of distinguishing between benign and malignant tumors, the proposed approach was to define the risk of aggressive behavior in GISTs and was based on tumor size and mitotic count to assign a risk (very low, low, intermediate, or high). Since the NIH risk criteria were first established, the primary tumor location has been identified as an additional prognostic factor. Several large studies have demonstrated that gastric GISTs have more favorable outcomes compared to small intestinal GISTs of similar size and mitotic count.72–74 The location of primary tumor has since been incorporated into the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) management guidelines for predicting biologic behavior of GISTs.76 Additionally, tumor rupture has been reported as an important prognostic factor in predicting survival, independent of tumor size and mitotic index.77

Summary of Risk Stratification Systems

| Prognostic Criteria | Risk Definition | Risk Groups | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NIH1 |

| Risk of recurrence |

|

| AFIP157 |

| Risk of recurrence | Groups 1-6b |

| Modified NIH158 |

| Risk of recurrence |

|

| MSKCC Nomogram78 |

| 2- and 5-year RFS | Individualized |

| Joensuu et al18 Contour maps |

| Risk of recurrence | Individualized |

A prognostic nomogram was developed at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) that assigns points based on tumor size (cm), mitotic index (<5 or >5 mitoses per 50 hpf), and primary tumor location (gastric, small intestine, colon/rectum, or other) to predict 2-year and 5-year recurrence free-survival (RFS) (Fig. 118-1).78 This nomogram applies to patients with localized primary GIST undergoing potentially curative resection. The nomogram was developed with 127 patients from MSKCC and validated using two large external databases. With a concordance probability of 0.77, the MSKCC nomogram demonstrated better predictive accuracy than the previously established NIH risk criteria.78

Figure 118-1

Nomogram to predict the probabilities of 2- and 5-year recurrence-free survival (RFS) in patients with resected localized primary GIST. A vertical line is drawn upward from the corresponding values of size (cm), mitotic index, and anatomic site to the points line. The sum of these points is then plotted on the total points line and a vertical line is drawn downward to determine the 2- and 5-year RFS. (Reproduced with permission from Gold JS, Gönen M, Gutiérrez A, et al. Development and validation of a prognostic nomogram for recurrence-free survival after complete surgical resection of localised primary gastrointestinal stromal tumour: a retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. November 2009;10(11):1045–1052.)

In addition to clinicopathologic findings, individual mutations have different prognostic value. As discussed previously, KIT mutations involving exon 11 demonstrate a higher rate of disease recurrence and are associated with a poor prognosis, especially if codon 557 and 558 are involved.49,52–56 GISTs with PDGFRA mutations typically have a lower risk of recurrence than GISTs with KIT mutations and are more likely to follow a less aggressive course.60 Patients with PDGFRA D842V mutations in exon 18 have demonstrated resistance to imatinib therapy.59

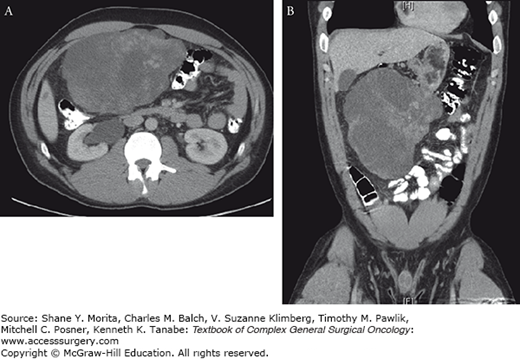

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis is the initial imaging modality of choice for GISTs. GISTs are typically well-circumscribed masses that most commonly displace, rather than invade, adjacent organs (Fig. 118-2). Large GISTs can appear to be heterogeneous due to focal areas of hemorrhage or necrosis within the tumor. GISTs can also demonstrate both endophytic and exophytic growth.79 Exophytic gastric GISTs abutting the pancreas may be initially misdiagnosed as a pancreatic mucinous tumor or pseudocyst.80 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used to further characterize metastatic disease involving the liver or for staging of rectal GISTs.81 While FDG-PET is highly sensitive, it is not specific for the diagnosis of GIST.15 FDG-PET has become useful in monitoring the response to tyrosine kinase inhibitors. In patients who respond to tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment, a marked decrease in the hypermetabolic uptake can be seen 1 month after initiating therapy, and as early as 24 hours after treatment begins.82 However, CT at 3 or 4 weeks is sufficient to determine response in most patients.

Upper endoscopy and colonoscopy may be useful in the diagnosis of GIST. Endoscopically, GISTs appear most often as a submucosal lesion that is indistinguishable from other gastrointestinal tumors of smooth muscle origin such as leiomyomas. Endoscopic ultrasound alone has not been found to be necessary in the diagnosis of GIST; however, when combined with fine-needle aspiration, diagnostic yield and sensitivity have been reported to be 78% to 82%.83,84 It is important to note that routine preoperative biopsy is not necessary for a primary resectable mass that is thought to be a GIST based on imaging. Routine biopsy, either endoscopically or percutaneously, comes with the risk that the tumor may bleed or rupture leading to dissemination of disease. Biopsy may be appropriate when the differential diagnosis includes other malignancies such as lymphoma that would result in a different treatment strategy. Additionally, preoperative pathologic diagnosis would be useful when metastatic disease is suspected that would ultimately guide neoadjuvant therapy.

While surgery has remained the mainstay of treatment for localized, primary GIST, the establishment of imatinib as a neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy has redefined GIST management. Conventional chemotherapy for the treatment of GISTs was associated with a poor response rate of less than 10%.85–88 Radiation therapy has a limited role as GISTs are relatively radiosensitive. In addition, the locations of GISTs make it difficult to deliver a cytotoxic radiation dose in close vicinity to vital organs. Hepatic artery embolization for treating liver metastases and intraperitoneal chemotherapy has also been explored and may have a role in tumors resistant to tyrosine kinase inhibitors.76 Imatinib is an oral selective inhibitor of KIT, PDGFRA, and BCR-ABL tyrosine kinases. The role of imatinib was initially explored in patients with metastatic disease, with up to 80% of patients demonstrating a radiographic response. These favorable results, in addition to a minimal side effect profile making it very tolerable by patients and its bioavailability as oral agent administered daily, have led to investigation into its role in the perioperative setting.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree