Introduction

Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is a common, life-threatening condition. The source of GI bleeding could be upper or lower or a combination of both. The type of GI bleeding also varies by amount of bleeding, which could be massive and clinically apparent in the form of haematemesis or haematochezia or it could be hidden or obscure. Upper GI bleeding (UGIB) refers to GI blood loss whose origin is proximal to the ligament of Treitz. Acute UGIB can manifest as haematemesis, coffee ground emesis and the return of bright red blood via nasogastric tube and/or melaena. Haematochezia could occur with UGIB when the bleed is brisk. Lower GI bleeding (LGIB) usually is defined as bleeding distal to the ligament of Treitz.

GI bleeding is a common geriatric problem.1, 2 In the United States, about 350 000 patients are hospitalized for UGIB each year3 and 35–45% of these are 60 years or older.4 The incidence of UGIB ranges between 50 and 150 per 100 000 population per year.5 Women 60 years of age account for 60% of UGIB.6 The mortality of UGIB has remained at ∼6–10% for the last 60 years.7–9 There is no difference in morbidity and mortality between young and old persons.10

The exact incidence of LGIB is not known,11 but the incidence of hospitalization is about 20–27 episodes per 100 000 persons per year, with a 200-fold increase with advancing age from the second to the eighth decades.12–14 Most patients with LGIB have favourable outcomes despite advanced age and other comorbid conditions.15, 16

The mortality for LGIB is 4–10% or greater and is more common with severe bleeding and those undergoing emergency surgery.17–19 Hospitalized patients admitted for other causes in whom bleeding starts in hospital have significantly higher mortality than those admitted already with LGIB (23 versus 2.4%). The independent predictors of all-cause mortality were increasing age, duration of hospital stay and number of comorbid conditions.12

Economic Impact

The economic burden of LGIB is not known, but is presumably significantly higher given the prevalence of this disorder in older adults. Thomas et al. estimated that diverticular haemorrhage alone cost US$1.3 billion in 2001.20 The average cost for a patient with LGIB in Canada is approximately US $3000 with an average length of stay of 7.5 days.21 The estimated direct and indirect cost of peptic ulcer disease exceeds US$9 billion per year.22

Clinical Presentation

It might be difficult at times to determine the accurate clinical presentation in older people because of poor vision or poor cognition, for example, providing a vague description of haematemesis versus haemoptysis. Haematemesis is defined as vomiting of blood and is caused by UGIB from the oesophagus, stomach or proximal small bowel. The blood may be bright red or it may be old and take the appearance of coffee grounds. Melaena is defined as passage of black, tarry and foul-smelling stools. The black, tarry character of melaena is caused by degradation of blood in the more proximal colon. Haematochezia refers to bright red blood from the rectum that may or may not be mixed with the stool. Occult GI bleeding denotes bleeding that is not apparent to the patient and is caused by small amount of bleeding. However, patients’ and physicians’ reports of stool colour are often inaccurate and inconsistent.23 In addition, bright red bleeding, could also be seen be seen from lesions in the right colon.24

The manifestation of GI bleeding varies with underlying medical problems; for example, a patient with underlying ischaemic heart disease may present with chest pain after brisk bleeding. Coexisting heart failure, hypertension, renal disease, diabetes, or pulmonary disease may be aggravated by severe GI bleeding, resulting in a shock. Some patients with chronic blood loss may present with signs of anaemia (weakness, pallor, dizziness, fatigue) or cirrhosis and portal hypotension. GI bleeding can also cause hepatic encephalopathy in patients with existing liver disease or develop hepatorenal syndrome. Orthostatic changes may be seen with moderate to severe bleeding.

Clinical Course

The hospital course of GI bleeding is similar in both young and older persons. The need for endoscopic therapy, admission to intensive care, blood transfusion requirements, need for surgery and length of hospital stay are not different.1, 10, 25 The length of hospital stay shortened from 1970–80 into the 1990s.25 In 1992 and 1994, the mean hospital stay for UGIB in older adults (>60 years of age) was 6.0 days compared with 5.6 days in those <60 years of age. Table 22.1 describes factors predicative of ulcer rebleeding and clinical factors leading to increased mortality in older adults. The risk of rebleeding is higher for arterial bleeding, adherent clot and non-bleeding vessels compared with clean base and flat spot. Also, mortality rates are higher for arterial bleeding compared with clean base.26, 27

Table 22.1 Clinical predictors of poor outcomes risks of rebleeding without endoscopic intervention.

| Clinical factors | |

| Haemodynamic instability (shock, hypotension) | |

| Bleeding manifested as haematemesis or haematochezia | |

| Failure of blood to clear with gastric lavage | |

| Age >60 years | |

| Coagulopathy | |

| Presence of underlying serious medical condition | |

| Hospitalized patients | |

| Endoscopic factors | Risk of rebleeding without endoscopic intervention (%) |

| Clean base | <3 |

| Flat spot | <8 |

| Adherent clot | 30–35 |

| Non-bleeding vessel | Up to 50 |

| Arterial bleeding | Almost 100 |

Causes of GI Bleeding

In the elderly, oesophagitis and gastritis in combination with peptic ulcer disease account for 70–91% of hospital admissions for UGIB. A greater percentage of patients with Mallory–Weiss tears, GI varices and gastropathy are seen in the younger population as a result of the greater degree of alcohol abuse in this age group.

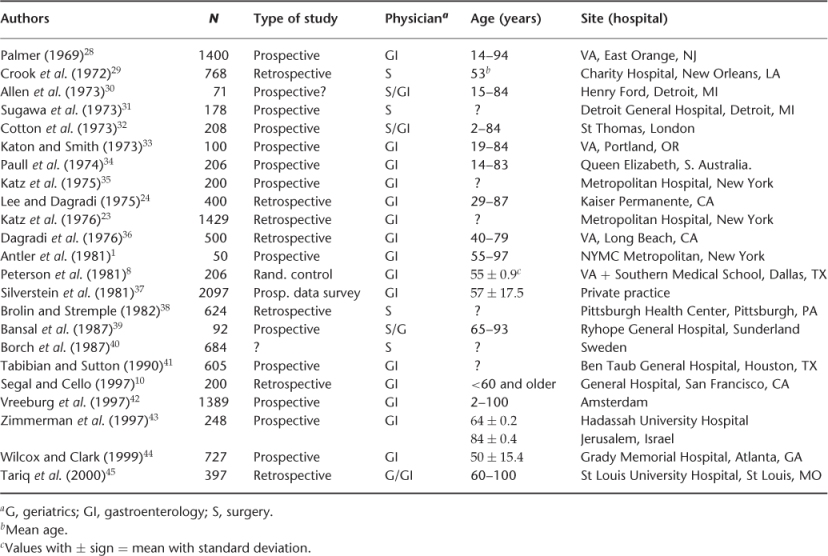

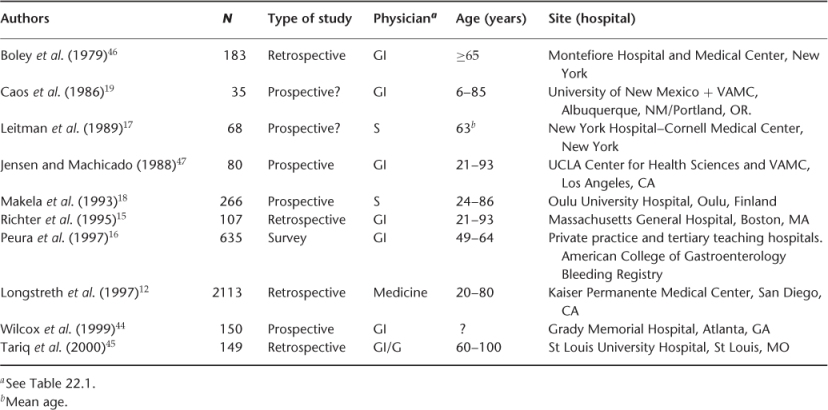

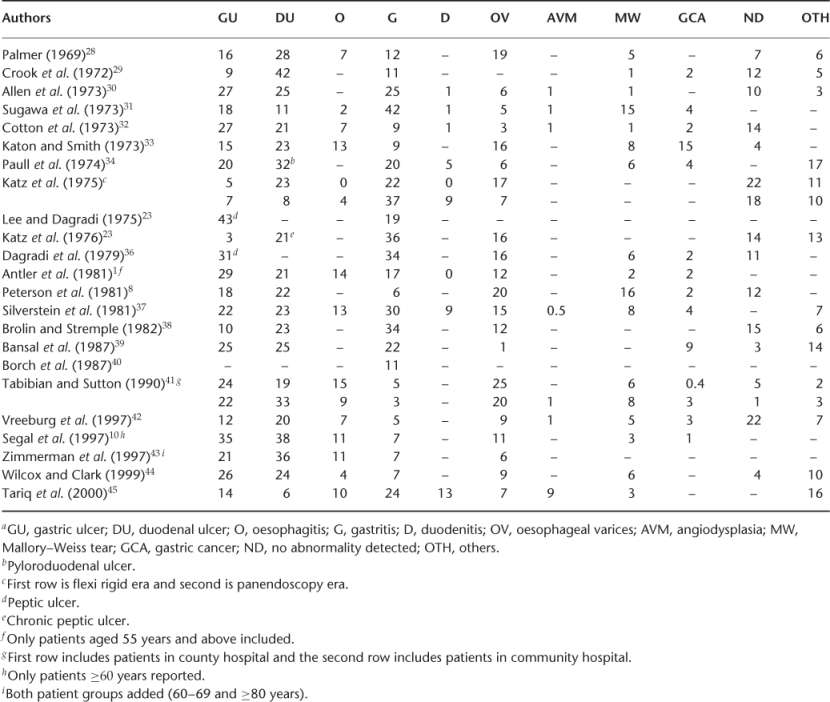

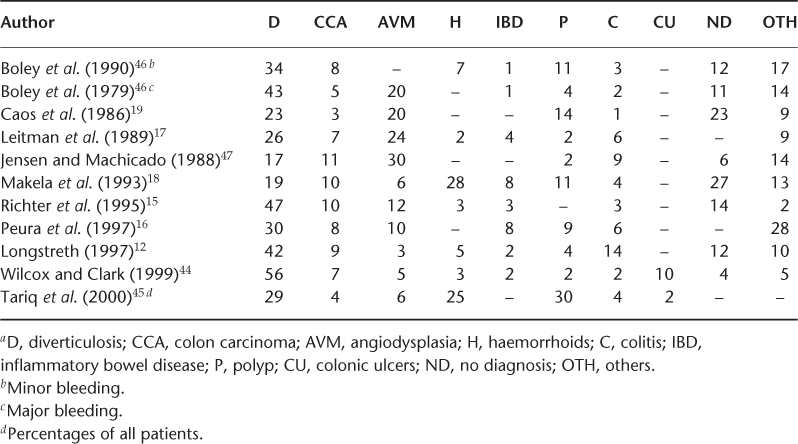

Tables 22.2 and 22.3 summarize the site of different studies, number of patients, age and physician by specialty involved for UGIB and LGIB, respectively. Table 22.4 shows the prevalence of UGIB in different studies. The prevalent UGIB causes are gastric ulcer (5–43%), duodenal ulcer (6–42%), gastritis (6–42%), oesophagitis (2–15%), oesophageal varices (1–20%), Mallory–Weiss tear (1–16%) and others (combination of lesions) (2–17%). The common causes of LGIB are summarized in Table 22.5, the prevalent causes being diventricular bleeding (17–56%), angiodysplasia (3–30%), haemorrhoids (3–28%) and polyps (2–30%).

Table 22.2 Studies examining upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

Table 22.3 Studies examining lower gastrointestinal bleeding.

Table 22.4 Causesa of upper gastrointestinal bleeding (%).

Table 22.5 Causesa of lower gastrointestinal bleeding (%).

Evaluation and Management of GI Bleeding

In this section the general evaluation and management of GI bleeding is discussed. For disease specific treatment refer to gastroenterology texts.

Initial Evaluation

The first step in the management of GI patients is stabilization with blood transfusion and other treatment deemed necessary before any diagnostic evaluation. If a patient’s initial blood pressure and pulse rate are normal, one can consider performing orthostatics to look for volume loss. Orthostatic changes are usually suggestive of 10–20% loss in circulatory volume; although supine hypotension suggests >20% volume loss. Hypotension with a systolic blood pressure of <100 m Hg or baseline tachycardia suggests significant haemodynamic compromise that requires urgent volume resuscitation. All patients require a complete history and physical examination: blood studies (platelet count, prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time); liver function tests, renal functions and complete blood counts. Determination of blood group and type and cross-match of 2–4 units of blood should be arranged urgently.

Seven independent predictors of the severity of acute LGIB have been identified: hypotension, tachycardia, syncope, non-tender abdominal examination, bleeding within 4 h of presentation, aspirin use and more than two comorbid diseases.48 These predictors can be helpful in classifying patients into three risk groups. Patients with more than three risk factors had an 84% risk of severe bleeding, those with one to three risk factors had a 43% risk and those with no risk factors had a 9% risk.32 In a prospective study of patients admitted with LGIB, three predictors of severity and adverse outcome were identified: initial haematocrit <35%, abnormal vital signs and gross blood on rectal examination.31

Volume Restoration

Restoration of intravascular volume is established by inserting two large-bore intravenous peripheral lines with an 18 gauge catheter or central venous line. Fluids used for resuscitation include normal saline, lactated Ringer’s solution and 5% hetastarch, with blood transfusion as soon as it is available to improve the oxygen-carrying capacity. Those patients who are in shock may need volume administration using infusion devices or vasopressors if clinically indicated.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree