8.1 Introduction

The study of food choice in humans involves many complex interactions, incorporating areas ranging from the biological mechanisms of appetite control, through the psychology of eating behavior, social and cultural values, to public health and commercial attempts to alter the food intake of particular populations. Food choice is apparent as both an outcome (an end) of a decision process and a mechanism or process (a means to that end). For nutritionists there is an increasing awareness that there are consequences with regard to both the end-point and the process. Understanding the factors that influence the development and changes in food selection are considered fundamental to aiding the successful translation of nutritional goals into consumer behavior. Many public health campaigns now recognize that biomedical research alone cannot address the major challenges of chronic disease prevention. Increasingly, government agencies seek to incorporate behavioral and social intervention strategies into public health interventions.

The overall aim of this chapter is to demonstrate to the nutrition student the relevance of applying the behavioral and social sciences to nutritional problems and to gain an insight to the complex interactions with nutrition in the process of food choice. This chapter will focus first on the population issues and then on the individual issues associated with food choice.

It is important to remember that the literature on food choice focuses predominantly, but not exclusively, on consumers in industrialized countries and therefore predominantly in Western cultures. As this chapter reviews the existing and established approaches to the subject much of the discussion will apply to such societies and cultures. It does not follow that such approaches are always valid in other cultures. A glossary of the terms used in the study of food choice can be found in Box 8.1.

- Acculturation: the process of cultural change from contact between cultural groups

- Attitude: a tendency, comprising affective, cognitive and conative aspects, which can be long or short-term, volatile and possibly amenable to change

- Behavioral traits: long-term dispositions for behaviors

- Commensality: eating food together

- Cultural flavor principals: the combinations of basic foods, herbs, spices and cooking methods that give foods characteristic sensory properties associated with particular cultures or regions

- Ecological validity: a quality of empirical evidence that reflects what is also observed in the real world

- Food deserts: areas of residence with few or no shopping facilities

- Food neophobia: a reluctance to eat and/or avoidance of novel foods (opposite of food neophilia: liking for new foods)

- Forced commensality: foods palatable to all participants at a shared meal, minimizing waste (adapted from commensality: eating food together)

- Hedonics: liking or disliking, the degree of pleasantness derived from stimuli such as food

- Perceived control: perceived ability to make dietary changes

- Psychohedonics: perceptions and preferences determined by pleasantness or hedonics (liking or disliking)

- Psychophysical perceptions (and possibly preferences) determined by the sensitivity of the physical senses

- Self-efficacy: perceived ability to make dietary changes

- Sensory-specific satiety or food-specific satiety: reduction in the perceived pleasantness of foods after a certain quantity has been consumed

- Shared cognitions: common ways of thinking about a food or meals, which may include attitudes and beliefs; one part (of three) of a definition of culture

- Standard operating procedures: agreed protocols for acquiring, preparing, cooking, eating and disposal of foods; one part (of three) of a definition of culture

- Subjective norm: the influence of important others (social influence)

- Unexamined assumptions: an attitude that shared cognitions and standard operating procedures are not generally questioned; one part (of three) of a definition of culture

8.2 The study of food choice

Often consumers’ initial response to a question asking why they choose a particular food is “because I like the taste”. Many people can rapidly give broad reasons for choosing foods. For example, a large European study focusing on influences on food choice highlighted quality and freshness, price, taste, trying to eat healthily and family preferences as the five most important factors influencing consumers’ choices. This is confounded, however, by how different consumers interpret terms such as “trying to eat healthily”.

Part of the problem with trying to understand the underlying reasons why consumers choose particular foods is that they are not always conscious of their reasons for choice. Marketing researchers often describe common foods as “low-involvement” products. Involvement in a product means that consumers find it very important and invest considerable time in acquiring knowledge of the product, facilitating more informed choices and the ability to express themselves. Such involvement may vary with the particular food or beverage. Wine could be considered to be a high-involvement beverage because of its intrinsic complexity (e.g. hundreds of volatile odors) and its social status at the meal table. These facilitate a large vocabulary (but not always with common definitions) allowing expression of opinions about wine qualities and preferences. The same cannot be said for, say, cooking oil, which could be considered a low-involvement food. Compared with other consumer products, such as cars, most foods would rate as low-involvement products. Nevertheless, particular groups of consumers, for example people who are very concerned about their body weight, may have a greater involvement with foods than others or with certain foods (e.g. energy-dense foods such as chocolate). Women, largely because of historical gender roles that persist in modern society (e.g. shopping, cooking and caring for their families), tend to be more involved with food than men. There are suggestions that some cultures are more involved with food than others; for example, within southern European cultures food is considered more important than among many sections of the UK population. What does this mean when trying to understand food choice? Simply, many people find it difficult to express the underlying reasons why they choose particular foods because of their lack of involvement. Confounding this is that there is no common vocabulary for expressing the attributes of foods. People were found to be confused between different tastes (sweet, sour, bitter, salt) and used other sensory descriptors (e.g. acidic) when asked to label tastants. Therefore, the term taste, when used colloquially, can mean many aspects of the sensory attributes of foods (Table 8.1) and different things to different people. Without a common definition it is difficult to compare across people or across foods. The challenge for investigators of food choice is to seek out the underlying reasons for choice when so many affective (e.g. sensory–hedonic), cognitive (e.g. attitudes, traits, beliefs) and external (e.g. availability, price, other people’s influence) factors are involved.

Table 8.1 Comparison of scientific and lay consumers’ definitions of “taste” (variations and aspects of taste or tastes further indicate the complexity of the term)

| Scientific definition of taste | Some lay understanding or use of the qualitative attribute taste | Some quantitative aspects (and scale anchors) that can interact with the attribute taste |

| Gustation, the five basica tastes (sweet, sour, bitter, salt, umamib) detected by taste receptors in the oral cavity | Tasty, salty, sweet, bitter, sour, acidic, mouthfeel, texture, smell, odor, pungency, flavorc | Strength (weak–strong) Duration (short–long) Quality (good–bad) Hedonics (liking–disliking) Ideal point (too little–just right–too much) Time intensity (peak perception over time) Aftertaste Off-taste |

a Not all scientists agree that there are five basic tastes.

b The fifth basic taste, umami, has no satisfactory English equivalent word; however, the closest could be “savory”. It is rarely reported by Western consumers.

c The term flavor is often used to describe a combination of odor, taste and pungency.

By definition, the term food choice implies a degree of volition, of control over the foods that people eat. However, it is often gauging how much choice and what influences choice that becomes the central focus. Measuring food choice relies on a range of methodologies, including observational approaches, interview, questionnaire and diary studies, controlled intervention trials, the use of animal models to understand basic mechanisms, and sensory preference trials in the laboratory and home.

Like nutrition, food choice is a complex area involving many different disciplines. Past studies have taken a transdisciplinary approach, which has sought to apply various disciplines to the food provisioning process: the acquisition, preparation, cooking, eating and disposal of food. Essentially, different disciplines have been applied to a process or problem. Such an approach has drawn upon the knowledge of social and economic scientists (from sociology, economics, marketing and anthropology) and therefore has tended to emphasize external or social factors in food choice.

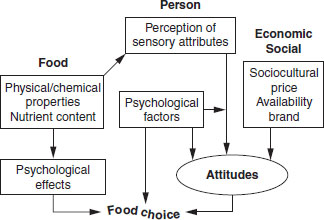

Other literature has been described as cross-disciplinary. This literature has been written by investigators from the behavioral (psychology, psychiatry and sensory science) and life (physiology, pharmacology, neurology and nutrition) sciences, but has also included marketing approaches. Such an approach has emphasized internal or individual factors associated with food choice. The areas of study tend to sit within models that locate those internal or individual factors within a culture, an economic system and a society (external factors). Different scientific backgrounds and differing collaborations have provided differing emphases on the understanding of food choice. It is therefore important to look carefully at the background of the investigators to see from which perspective they approach problems of food choice. This chapter emphasizes socioeconomic and psychological approaches to food choice, with some reference to physiology. Reference should be made to the chapter on sensory systems in Nutrition and Metabolism. Personal attributes will also have a major modifying effect on physiological reactions. These include perception of sensory attributes (e.g. taste, texture), psychological factors (e.g. mood, cognitive factors such as attitudes) and the social environment (e.g. cultural norms, advertising, economic factors and food availability). Various schematic models have been devised which attempt to show how factors influencing food preferences and choice interact. A popular model of food choice is shown in Figure 8.1.

Understanding the processes of food choice at an individual level is complex. It has been observed that people’s life course experiences affected major influences on food choice that included ideals, personal factors, resources, social contexts and the food context. These influences, in turn, informed the development of personal systems for making food choices that incorporated value negotiations and behavioral strategies.

Figure 8.1 Shepherd’s model. From Shepherd and Sparks (1999). Reproduced with permission from Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

8.3 Population issues affecting food choice

Behavior (such as eating), social and economic factors, and people’s beliefs and attitudes when applied to a population or ethnic group collectively can be labeled as cultural factors influencing food choice. This section explores cultural factors and the sociology of food choice.

Cultural factors

It is thought that culture is a major determinant of human food choice. Indeed, there is evidence that traditions, beliefs and values are among the main factors influencing preference, mode of food preparation, serving and nutritional status.

The psychologist Triandis provided a useful review of many different definitions of culture and concluded that most people agreed that culture was reflected in shared cognitions, standard operating procedures and unexamined assumptions. A common theme in most definitions is that of sharing. By whatever definition (and culture is a difficult phenomenon to define), food is almost always generally considered to be major part of culture, and culture is considered to be the major influence upon food choice, specifically, a culture shares certain food choices.

Genetics or cultural influences?

Explanations for cultural food choices and preferences for particular varieties of foods have been sought in terms of differences in the perceptions of the sensory characteristics of foods. Early cross-cultural studies focused on comparison of sensory perception such as threshold, sensitivity or discrimination. Most studies looking at perception of tastes in solutions found no differences between cultures. No difference was recorded in the four basic taste (salt, sweet, bitter, sour) thresholds between Nigerian, Korean and American subjects. There is some emerging preliminary evidence that odor perception may differ between Japanese and Europeans; however, this requires more substantiation. Despite the lack of research into cultural differences in perception of sensory properties other than tastes such as flavor or texture, chemosensory abilities appear generally similar between cultures. It is well accepted that there is evidence of variation between cultures in preference for food. Research has looked at cultural patterns for liking of specific sensory properties. Taste intensity liking has been found to vary between cultures depending on the context or food. Overall, cultural variation in taste level preference seems to be product specific, with no consistency in direction or magnitude across products. These product-dependent differences appear to be related to consumer familiarity and exposure. Therefore, cross-cultural variation in food preferences appears to arise from experience, dietary habits and attitudes to food, rather than a strong genetic influence. Nevertheless, within cultures emerging evidence suggests that there is a genetic component to various food behaviors at an individual level, including stomach filling, dietary restraint, eating companions, susceptibility to social facilitation and possibly palata-bility of highly palatable foods.

Cultural flavor principles

Flavor principles have been suggested to characterize particular cultures food preferences. For example, tomato, olive oil, garlic and herbs are characteristic of certain cuisines of Mediterranean countries or regions. Cuisine can be structured as:

- basic foodstuffs

- manipulative techniques (particulation, incorporation, separation or extraction, marination, fermentation and the various applications of heat)

- cultural (or regional) flavor principles.

The historical perspective given to these shared processes and cultural favors introduces the concept of exposure and familiarity, which has been demonstrated to be a significant predictor of food acceptance.

Biology, culture and individual behavior

Chili, corn, manioc and sugar have been used as examples to illustrate the way in which culture and individual behavior influence and modify biology. A biological aversion to chili peppers (which contain a hot irritant) may be overridden by culture (culinary behavior) and individual psychological processes. The manioc (cassava) example sought to show how biological problems (the toxicity of manioc, perceived by the bitterness of the tuber) were overcome by processing (individual behavior) and how such processing became integrated into culture (the detoxification technology), leading to individuals using the technology and accepting the food. A nutritional example was that of corn (maize). The poor niacin, amino acid and calcium content of such a staple food (biological problem), the discovery of processing with added lime and the making of tortillas (individual), and the acceptance of such technology and cuisine (culture) led to the acceptance of corn tortillas as a staple food. However, the biological component (nutrient deficiencies) may have been overcome through the enhanced sensory acceptability route, as the addition of lime softens the corn, creating perceptions of greater palatability. In these ways culture, biology and individual behavior interact with respect to food choice.

Cuisines are rarely static; indeed, the traditional food itself is not unchanging. Tradition has been defined as “a sequence or variations on received and transmitted themes” and several scenarios of how traditional cultural cuisines change, resist change or move across national boundaries have been documented.

Cultural food choices and potential benefits to other populations

The landmark studies of Keys in the 1950s of the “cultural” Mediterranean diet led to attempts at changing trends in food choice in the latter half of the twentieth century in many industrialized countries. There has been consensus for some time on increasing fruit, vegetable and grains in the diets of Western industrialized populations, and similarly in reducing fat or, more recently, consuming different fats (e.g. less saturated and more poly unsaturated or monounsaturated fats). These can be perceived as an attempt to use one food culture in other cultures. For example, people of Anglo-Celtic origin appear to have low intakes of fruit, vegetables and grain foods compared with southern Europeans (Italians and Greeks). Data on the eating habits of Italians and Italian migrants supports a resilience of the desirable features of the Mediterranean diet. Retaining aspects of the Mediterranean diet and encouraging its consumption in other cultures may be a useful public health nutrition strategy. An understanding of food choice is crucial in this respect.

Cultural influences and the rise of the global marketplace

In the early 1980s it was asserted that, with a global marketplace, products, including foods, were becoming standardized worldwide (or at least in the developed world) and that consumers would develop homogeneous preferences. However, this view has subsequently been modified and there is increasing consensus that certain marketing parameters may only be standardized to varying degrees, depending on the market, the product, the company and the environment.

In some respects, homogeneous preferences for “fast foods” have increased enormously since the early 1980s. Such foods may be part of a global culture of increasing perceived time poverty or choices to allocate time to other activities. These changes may have important consequences for nutritional status and deserve considerable investigation.

Cultural integrity

Evidence from some of the rapidly industrializing countries of Asia provides examples of resistance to homogeneous food preferences. For example, the food choices of Koreans and Chinese Malaysians have resisted changes and remain culturally intact. It is notable in that the South Korean economy has industrialized rapidly since the 1950s, yet the traditional foods and cuisines associated with Korean diets have been retained. As a consequence, nutrient intakes have, in comparison to other rapidly industrialized Asian countries, changed little. Contact with people of one’s own culture has been shown to help maintain cultural behaviors, including food habits. In contrast, the Malay Malaysian community appears to be developing more Westernized diets with associated recent increases in chronic diseases such as heart disease and certain cancers found in Western industrialized nations. It is largely unknown which factors are most important: social, self-identity or even sensory attributes of the foods. Nevertheless, certain cultural cuisines appear to resist changes while others, even in the same country, appear to be more open to modification.

Acculturation

Acculturation is defined as “the process of cultural change from contact between cultural groups”. The process of migration and immigration demonstrates how food choices can resist or be influenced by cultural change, and several cross-sectional studies of acculturation have assessed migrants to Western cultures. For example, Korean migrants living in the USA consumed more “American” foods if their acculturation was greater. In a sociological study of South Asian females living in Scotland, it was found that, in contrast to Italian migrants, fat intakes had increased markedly with migration, with an associated increase in body mass index (BMI), and incidence of heart disease and type 2 diabetes. Various possible mechanisms were described, such as body image, gender/cultural roles and the value of certain foods. British-born South Asians were more marked in this respect than Asian-born South Asians. However, South Asians placed much more emphasis on traditional foods for formal meals than their Italian counterparts, who appeared to be more flexible in their culinary choices, choosing Anglo-Celtic foods more often.

Australia presents an intriguing case as 98% of its population is migrant. The country has been dominated by white Anglo-Celtic culture, but, especially during the latter half of the twentieth century, has witnessed large migration from southern Europe (bringing a Mediterranean diet) and, since the 1990s, from Asia. Since the 1970s, Australian food choice appears to have become increasingly diverse, nevertheless, there is some evidence that distinct cultural preferences and beliefs about foods have been retained in the populations of Anglo-Celtic and Mediterranean origin. Evidence of Asian migrants’ distinct food preferences is illustrated by a study of Vietnamese women resident in Australia who were found to have retained distinct food preferences and dietary profiles, particularly with regard to staple or core foods. Changes in food intakes occurred most among those who had migrated at an earlier age, which is consistent with considerable research on the development of children’s eating habits.

In contrast, North American studies including data on Chinese migrants to the USA and Canada, and Korean migrants to the USA provide evidence for increasing similarity between migrants and the host cultures in terms of nutritional status as a function of greater acculturation. A Canadian study notes changes in perceived flavor, health and prestige value of foods among young boys suggesting, again, that age of migration, with consequent impression and early exposure, is important. It is possible that food choices remain culturally specific, while the relative quantities of foods move towards those of the host nation’s culture, with consequent changes in macronutrient intakes. The resilience of the Korean diet in Korea, in contrast to Korean migrants to the USA, suggests that US cultural effects are stronger than mere changes in economic circumstances.

Acculturation is a complex phenomenon requiring multidimensional measures, and the evidence suggests that the end result of acculturation is not simple assimilation by the dominant host culture. Whereas cultural food choices appear to remain resilient, especially for core staple foods, changes in macronutrient intakes appear, in some cases, to move towards the host culture. Age and generation appear to be key factors and fit with the principles of early exposure and availability. However, as all studies cited are cross-sectional, relying on length of residency as a marker for changes over time, there is a need for longitudinal studies.

Media and advertising

The media, especially television, may be one of the most important sources of information about food. Government data suggest that in the UK, children aged 4–15 years spend between 17 and 18 h/week watching television, via which most food and drink images are conveyed through advertising. By the time children in the UK leave school, the time devoted to watching television will exceed the hours spent in school. Within Europe, the UK has the highest level of advertising targeted at children, while Sweden and Norway have no child-directed advertising. Most studies of the content of television food advertising highlight that a significant proportion of food adverts is for high-fat or high-sugar foods, and concern has been expressed that overweight children may be particularly sensitive to these. However, the issue remains controversial; there is no evidence to suggest that advertising is the principal influence on children’s eating behavior, and it is likely to be just one influence among many factors.

The impact of advertising on children’s dietary knowledge, attitudes and behavior is unclear. Food advertising is known to increase children’s knowledge of brand names, to foster positive attitudes to the food and to change beliefs, but few long-term studies have monitored and quantified these effects. Children exposed to a cartoon program containing food advertisements made more bids for the advertised foods than children in a control condition. Research has demonstrated that if children enjoy a commercial and are interested in its content, their requests to have a particular food increase. Public health messages delivered to young children with adult reinforcement of the positive value of more “healthy” foods have been shown to decrease consumption of less healthy snacks by young children. It has been demonstrated, in a naturalistic setting, that the more television advertising a child sees for a particular product marketed specifically for children, the more likely it was that the product would be found in the child’s household. Thus, media messages can be influential in determining requests for food items and in food selection, at least in the short term.

Food access and availability

The concept of food availability stretches from local retail provisioning to availability within the home and catering settings (notably school food provision). Food retailing is major business and a source of consumer pleasure and concern. Throughout Europe, the number of retail outlets has diminished as larger supermarkets have developed. For example, in France retail outlets have declined from 200 000 in 1986 to 150 000 in 1990, and in Italy the number of retail outlets dropped by 15% between 1985 and 1993. In the UK the number of independent food stores declined by almost 40% between 1986 and 1997. Although providing the benefits of lower costs through economy of scale to both retailers and consumers, such a concentration of retail outlets requires that consumers have access to transport, most often the private car.

Adequate food at affordable prices is necessary if people are to have access to a healthy, balanced diet. Such access can be influenced by area of residence, car ownership, public transport, and shopping and storage facilities. Access is generally considered a major factor in compliance with dietary recommendations. In the UK, concern has been expressed over the problem of areas of residence with few or no shopping facilities, known as “food deserts”, as a contributor to health inequalities. Several studies have reported higher shopping costs for “healthy” than for “less healthy” shopping baskets, and variation in costs in different urban areas of residence. A UK independent inquiry has recommended the development of policies to ensure adequate retail provision of foods to those who are socially disadvantaged. Studies in a deprived urban area in London demonstrated a four-fold difference in price between the cheapest and most expensive food prices in the area. Less than one-third of the foods that would contribute to a basic basket for a healthy diet were stocked in most outlets. However, this observation is not universal.

Within catering settings, changes in food accessibility and pricing have been shown to lead to increases in fruit and salad purchases, and decreases in the selection of confectionery and crisps. Availability of quality and variety almost certainly also influence consumption.

Social influences on food choice

Food habits are generally developed and maintained because they are effective, practical and meaningful behaviors in a particular culture. However, society refers to the people who participate in the culture, and the characteristics of those people will, in turn, affect dietary intake.

Sociodemographic factors

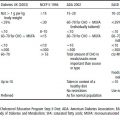

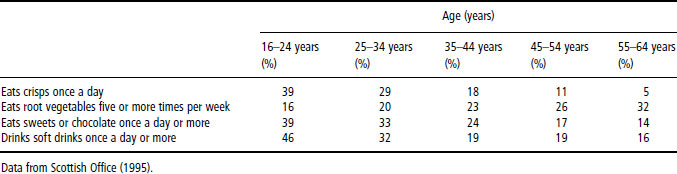

Food choices are socially patterned with the key sociodemographic variables of age, gender and social class, but also with ethnicity, marital status and household composition, and a range of psychosocial and intervening variables (Figure 8.1). Age will affect dietary intake through a range of biological processes (e.g. growth), current contexts and fashions, social factors and psychological factors. Even during adult life there are marked differences in food consumption (Table 8.2).

From birth it is clear that nutritional wisdom will be modified by social pressures, normative behaviors and practical constraints. Breast-feeding is a good example of this (see Chapter 16). Throughout the lifespan biological needs will interact with social factors in the formation, development and maintenance of eating behaviors. Thus, in early childhood the social construction of meanings about food by teachers and pupils intersects with the policy and provisioning within schools. Likewise, in adolescence, emotions such as resentment, anger and frustration may find expression through eating habits by spitting, throwing and mashing, or through physiological responses of nausea, gagging or vomiting. In older years some authors suggest that access to food and the cost and quality of food impact upon food habits, resulting in a contrast between stated food beliefs and actual consumption patterns.

Table 8.2 Frequency of food consumption by age of adults in the Scottish Health Survey, 1993

Even from early childhood it is recognized that food intake varies by gender. Dietary surveys in Europe have highlighted differences in food consumption between men and women, with men having higher intakes of meat products, alcohol and sugar, and lower intakes of fruit, vegetables and low-fat products than women. In some respects these choices make women’s diets more consistent with current recommendations than men’s; however, women’s intakes of micronutrients, for example, iron, zinc, vitamin B12 and folate, are often deficient, particularly when biological requirements are greater.

Biological, social, psychological and behavioral factors associated with gender appear to interact to influence the intake of different foods and nutrients. In general, women have lower energy requirements than men owing to lower body mass. Socially, it may be considered less acceptable for women to be seen to eat large quantities of food in a culture where excess body weight is considered undesirable. Women seem to be more knowledgeable about food and nutrition and indicate higher levels of concern over food safety, health and weight reduction. Men appear to have stronger beliefs and values associating certain foods items with qualities such as strength, power and virility, and consumption may be used as a symbol of masculinity. It has also been argued that specific foods and types of meal function as symbolic markers of gender and of gender status within the nuclear family.

Social class or socioeconomic variations in food consumption are of particular concern with respect to health inequalities. Various measures have been used to access socioeconomic position, including occupation, income and education. Class is assumed to have an economic base, is measured by income or occupation, and implies some control over resources.

People belonging to higher social class groups and with a higher educational level tend to have healthier diets. For example, they have higher intakes of fruit, fruit juices, lean meat, oily fish, wholemeal products and raw vegetables compared with manual workers, who have higher intakes of energy (presumably to match energy requirements) and lower intakes of polyunsaturated fatty acids, fruits and vegetables. It is also assumed that groups with higher socioeconomic status have healthier diets because they are more health conscious and have a healthier lifestyle. Higher educational levels may also help to conceptualize the relationship between diet and health.

Disposable income and the amount of money to spend on food are also crucial factors in food choice, especially for meat, fruit and vegetables. The evidence on the relationship between diet and poverty in Europe suggests that people in low-income households are not ignorant of food issues, but are in fact highly skilled at budgeting, especially where food is often the only flexible item in the household. In the UK, households in the lowest decile of income spend the highest proportion of money on food. Data from the UK National Food Survey show that poorer households are the most efficient purchasers of nutrients per unit cost. There is also some evidence that foods that are currently recommended for a healthier diet not only cost more than cheap, filling, energy-dense foods, but are also more expensive to purchase in areas of rural and urban deprivation.

Social factors at the household level

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree