14.1 Introduction

Fear of fatness (body dysphoria) may be described as a culture-bound syndrome in that it appears to be limited to a number of cultures with similar psychosocial features. In the modern world the factors that foster fatness phobia appear to prevail in Western cultures or cultures strongly influenced by them. Nonetheless, several reports suggest that fatness phobia is not a modern phenomenon, while others propose that Mary Queen of Scots (b. 1542, d. 1587) and the Empress Elisabeth of Austria (b. 1837, d. 1898) may be included among the many women affected. Fatness phobia can be largely explained by the stigmatization of obesity and this is not exclusive to modern Western societies. For example, during medieval times, fatness was considered to be the Karmic consequence of a moral failing in the Buddhist context, while in Europe such a stigma was based on the Christian deadly sin of gluttony. Furthermore, cases of anorexia occurring in the sixteenth century and earlier have been referred to as holy anorexia because such dietary restraint was predominantly associated with religious life. Indeed, such origins may explain the severely abstinent and self-denying characteristics of modern-day anorexia nervosa and the “good” connotations of dietary restraint as opposed to the “sinful” connotations of breaking a diet.

From 1600 up to our own times anorexia has been described as becoming more of a concept that depends upon, and reflects, the changing directions of medical fashion from physical, psychiatric and sociocultural viewpoints. The importance of cultural and societal factors for defining pathological eating behaviors can be appreciated by considering how the typical eating behaviors of bygone days would be viewed today. For example, the everyday eating habits of the Romans during the first two centuries AD, including the bulimic behaviors of the Roman emperors Claudius and Vitellius, were not considered abnormal at the time, but would certainly be considered pathological nowadays.

Anorexia nervosa and bulimia are recognized eating disorders requiring clinical and psychological management. Fear of fatness is a necessary precursor of these eating disorders, but the majority of people obsessed with body image and exhibiting this fear of fatness do not go on to develop clinically manifest eating disorders. Because it is so widespread, fear of fatness is a very significant public health issue and is the primary focus of the present chapter.

14.2 Epidemiology

Fear of fatness affects far more women than men, which explains why the quest for slenderness is largely regarded as a female matter. Fear of fatness and fad dieting may persist even during pregnancy. After controlling for body weight, white women living in Western societies, or cultures strongly influenced by these, have been shown to be the most vulnerable to fear of fatness. However, other studies have shown that among women who diet within the vulnerable societies, unhealthy eating attitudes and practices may be similar regardless of their ethnic background. Apart from Japan, there are very few quantitative studies on eating disorders from Asian, Middle Eastern, Hispanic or African countries.

Adolescent girls are recognized as being most at risk and in vulnerable societies it is estimated that up to 70% may be affected. Fear of fatness is so pervasive among adolescent girls that is has been referred to as “a normative discontent” for this age and gender group. However, fatness phobia starts well before adolescence and studies indicate that children as young as 9 years try to lose weight, with roughly double the number of girls affected compared with boys.

After adolescence, the lasting effects of fear of fatness were described in a 10-year follow-up study of American college students. Although this study showed that women experienced an overall decline in body weight concerns as they matured into adulthood, many of those who were dissatisfied with their bodies continued dieting and engaging in disordered eating. While few women who were satisfied with their weight and shape in college developed weight phobia and eating problems in adulthood, quite a different picture emerged for the men involved in the study. More than half of these men gained more than 4.5 kg (10 lb) in the 10 years after leaving college and their body weight concerns, eating-disordered attitudes and behaviors were found to increase accordingly.

During adulthood, the largest natural fluctuations in body weight and body fatness occur during pregnancy. In general, slenderness does not seem to be important for female appearance during pregnancy and this condition has been shown to legitimize increased food intake. Nevertheless, although studies suggest that fear of fatness and associated unhealthy slimming behaviors diminish for many women during pregnancy, this is not a universal trend. There are reports to suggest that a significant minority of pregnant women continue to control their weight gain by restraining their food intake, purging and smoking. Such behaviors during pregnancy have been associated with the delivery of babies who are small for gestational age. Although women having a past history of an eating disorder are more likely to restrain food intake during pregnancy, studies have shown that this background does not predict intrauterine growth retardation. Therefore, the possibility of restrained eating owing to fear of fatness should be considered in cases where intrauterine growth is of concern, even among women without a history of pathological eating behavior.

At any age men, compared with women, are generally more positive about their body physique and figure, and are less affected by fear of fatness. Studies comparing older and younger women indicate that although those in younger age categories are the most vulnerable, elderly (60 to over 65 years old) women continue to have body weight concerns and share the same trait of wanting to be thinner despite being of normal weight.

14.3 Life-cycle fatness trends

It is only during the first year of life that males and females are similar in terms ofbody fatness levels. Both genders experience significant changes in fatness levels over the life cycle. An understanding of these variations in body fatness levels helps to provide some insight into fear of fatness and why some age and gender stages are more vulnerable than others.

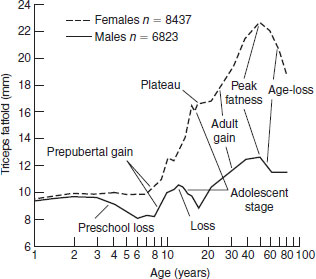

The Ten State Nutrition Survey of 1970 measured triceps and/or subscapular fatfolds in more than 40 000 individuals, generating a database covering nine decades of life in both white and black Americans. A report from this study included a graphical description of trends in fatness over the life cycle given as median triceps skinfold for the white participants in this study (n = 15260). This graph, plotted on a semilogarithmic scale to emphasize changes during the first two decades, is included here as Figure 14.1. Overall there were similar trends in fatness levels over the life cycle evident for the black participants in the study (data not shown). The slight differences between white and black people that emerged at particular stages are discussed below. As illustrated in Figure 14.1 males at all ages are leaner than females; however, these differences are more significant during certain stages of development. While fatness levels in girls remain stable until the prepubertal gain, boys experience a reduction in fatness during the preschool period. However, it is during adolescence that the most significant gender differences in fatness develop. Under the influence of the sex hormones, these differences not only affect body composition, but also affect body shape as gender differences in how fat is distributed over the body occur. While a surge in body fatness is characteristic of female adolescence, boys tend to experience some depletion in levels of body fatness during this time. Testosterone in boys influences the development of lean tissue, while estrogen and progesterone in girls promote the deposition of body fat and the development of new fat stores in the gluteal and femoral regions. As they mature these fat stores will form the typical pear-shaped body fat distribution of adult women. At all life stages, the adult male remains significantly leaner than his female contemporary. A comparison of black and white people, in this study found that from the third year of life onwards, white males tended to be fatter than black males. White females were found to be fatter through adolescence, after which the difference was reversed, and after the age of 17 years black females tended to be considerably fatter than white females.

Figure 14.1 Life-cycle fatness trends in females (broken line) and males (solidline) as shown for more than 15 000 white participants in the Ten State Nutrition Survey. From Garn and Clark (1976). Reproduced with permission from Pediatrics, volume 57. © 1976.

The fact that women are significantly fatter than men throughout life explains to some extent why preoccupation with body fatness levels and fear of fatness is predominantly a female issue. Consideration of the physical changes that girls undergo during adolescence compared with those experienced by boys provides some insight into their particular vulnerability to fear of fatness. The marked increase in fatness levels during female adolescence is rapid in onset and permanently alters body shape. Psychosocial adjustment to such dramatic physical changes, which occur within a short timeframe, can be very difficult, especially for girls living within societies where slenderness is highly valued. At the same time, the tendency towards leanness in boys during this growth phase indicates why, in general, body fatness is not an issue for them. Furthermore, boys cannot be directly compared with girls of the same age during adolescence because they develop later and in biological terms tend to be 2 years behind girls of similar chronological age. Other factors that impact on these life-cycle fatness trends to cause fatness phobia and fad slimming diets are explored in Section 14).5.

14.4 Definitions and descriptions

Fear of fatness

Definition

Fear of fatness is a general term used to describe aversion to fatness accompanied by weight-loss attempts that are unrelated to body size and which do not meet the criteria for diagnosis of a defined eating disorder.

Description

There is a spectrum of pathological eating behaviors associated with fatness phobia. Anorexia and bulimia represent the severe end of the scale. Although those affected by these serious eating disorders and those who are more mildly obesity phobic may indulge in similar unhealthy slimming practices, there are significant differences in the severity of their symptoms. The slimming behaviors of relatively few of the many individuals affected fulfill the strict diagnostic criteria for diagnosis of anorexia or bulimia nervosa. Therefore, the more prevalent milder variants of these serious eating disorders tend to be collectively described by the general term “fear of fatness”. In general, this describes aversion to body fatness or dissatisfaction with weight and/or shape that is unrelated to body size and which is accompanied by unhealthy weight-loss attempts.

A feature of fear of fatness is that many of the individuals affected perceive themselves to be significantly fatter than they actually are (body image disparagement), while the remainder continue to slim despite recognizing that they are not overweight. This results in inappropriate slimming behaviors among those who are of normal weight or are even underweight. Typical unhealthy weight loss behaviors include random avoidance of staple foods such as meat and dairy, skipping meals, fasting, taking diet pills, smoking, inducing vomiting, abusing laxatives and diuretics.

Fad slimming diets

Definition

Fad slimming diets involve patterns of food and fluid intakes that are promoted as having the ability to induce rapid or permanent weight reduction owing, it is usually claimed, to some intrinsic components which are based on unscientific principles. Such fads may or may not be accompanied by special nutritional or herbal supplements. Fad diets have also been defined as any plan failing to match the needs of the person.

Description

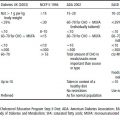

To describe fad slimming diets it is reasonable to start by considering the factors that distinguish fad and sound approaches to the dietary treatment of obesity. Program checklists to aid avoidance of fad slimming diets have been developed and an example is given in Table 14.1. This checklist includes 10 crucial questions whereby the soundness of a slimming diet or program can be assessed. A description of the different domains covered by this checklist is outlined in the text that follows. While many of these questions cover distinct areas, the scope of others target similar concerns but from different angles.

Sound slimming diets: a checklist

The first question, which obligates the dieter to seek medical advice before following the diet, concerns safety.

A medical opinion helps to ensure that the special needs of individuals, such as growing children and pregnant and nursing mothers, are protected. Other examples include individuals with chronic conditions, which may or may not be related to their obesity. For example, in association with increasing fatness trends growing numbers of people are being diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. Although these individuals will benefit from weight loss, their weight-reducing diets and medication regimens (where appropriate) require careful adjustment to avoid fluctuations in blood sugar levels. Gout is another example of an obesity-related condition that may be exacerbated by weight loss that is too rapid.

The second question, concerning the involvement of a suitable qualified health professional in the design of the diet or program or for follow-up consultation, is another endeavor to ensure that health is not compromised while following the diet. The involvement of a professional who is specially trained in nutritional science is necessary to ensure that the diet provides all micronutrients adequately and is balanced to maximize fat loss while preserving lean tissue.

The third question concerns using established standards to define weight loss goals. This is important to protect those who do not need to lose weight and to set realistic goals for those who do. Although the body mass index (BMI) is usually the standard of choice, care must be taken that it is used appropriately; for example, the standard 20–25 kg/m2 does not apply to children, adolescents or some athletes, and may be unsuitable for those over 65 years of age. Finally, sound programs involve weight loss goals that are realistic, which may involve some flexibility in the standards used; for example, the BMI goal may exceed 25 kg/m2 for very obese individuals.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree