Cross-section anatomy of the eye, orbit, and eyelids: (A, B) posterior lamellae of eyelid, (C) orbital septum, (D) orbital fat, (E) superior fornix and conjunctiva, (F) inferior fornix and conjunctiva, (G) sclera, (H) cornea, (I) anterior chamber, (J) iris, (K) lens, (L) zonular fibers, (M) ciliary body and muscle, (N) vitreous body, (O) retina, (P) choroid, (Q) optic nerve, (R) central retinal artery, (S) levator muscle, (T) superior rectus muscle, (U) inferior rectus, and (V) inferior oblique muscle.

The major function of the eyelid is to protect the surface of the globe. Additionally, it serves to distribute the tear film across the optically clear cornea. The tear film is integral in protecting the cornea and ensuring vision. The tear film serves multiple functions to the underlying cornea including providing (1) lubrication and protection, (2) a smooth optical surface, (3) antimicrobial properties, and (4) necessary nutrients. The tear film is composed of three layers: lipid, aqueous, and mucin. The meibomian glands, sebaceous glands, and apocrine glands produce the lipid layer of the tear film that serves to slow evaporation of the aqueous tears. The aqueous portion is produced by the lacrimal and accessory lacrimal glands. Conjunctival goblet cells produce the mucinous layer, which assists in the adherence of the tear film to the ocular surface. The tears drain via the upper and lower lid puncta, canalicular system, nasolacrimal sac and nasolacrimal duct to exit beneath the inferior turbinate of the nose.

Abnormalities of the eyelid are particularly important to recognize in the setting of conditions that may cause the eyelid not to close completely. In those cases, special attention is needed to ensure all functions of the eyelid are met using other means, such as artificial tears.

Eyelid structural changes associated with aging

Structural changes of the eyelid can affect an older adult’s vision both by physically obstructing the visual fields and preventing the eyelid from performing its vital protective functions. These eyelid malpositions may produce tearing and ocular discomfort secondary to mechanical irritation of the cornea or failure of the eyelids to protect and lubricate the cornea leading to exposure keratopathy. Medical therapies with aggressive lubrication may be a temporizing measure, but the definitive treatment of these structural changes is generally surgical.

Dermatochalasis is the most common eyelid change observed in the elderly. It is characterized by a progressive laxity and resulting redundancy of eyelid skin, which can obstruct the superior visual field. This condition may be associated with blepharoptosis or ptosis, both commonly due to stretching or dehiscence of the lavatory aponeurotic. Blepharoptosis is abnormal low-lying upper eyelid margin obstructing the superior portion of the cornea. Ptosis is the drooping of the upper eyelid.

Horizontal eyelid laxity can cause lagophthalmos, or the inability to close the lids completely. Entropion, or the inward rotation of the eyelid margin, may result from involutional changes or chronic scarring processes of the conjunctiva, such as Stevens-]ohnson syndrome or ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. This may be accompanied by trichiasis, or malpositioned eyelashes. Ectropion, the outward rotation of the lid margin, may be a consequence of involutional, cicatricial, paralytic, or inflammatory processes of the skin, orbicularis oculi muscle, or lid retractors. Structural changes can also be a common cause of chronic tearing, or epiphora. Obstruction of any portion of the lacrimal drainage system can cause epiphora. Involutional stenosis of the nasolacrimal duct is the most common type of nasolacrimal duct obstruction in elderly persons.[6] The treatment of the obstruction is dependent on the location. If the lacrimal “pump” (lid laxity) is the etiology for tearing, treatment is a lid tightening or ectropion repair. Punctal stenosis can typically be treated by a short in office procedure (punctoplasty). A lacrimal sac and nasolacrimal duct obstruction require silicone intubation and dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR). The DCR procedure requires the creation of a bony ostium between the lacrimal sac and the nasal cavity. A complete workup for epiphora would involve investigations into dry eye and blepharitis, both of which are discussed in this chapter.

Eyelid neoplasms

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common malignancy of the eyelids, accounting for more than 90% of eyelid neoplasms. Risk factors for BCC include fair skin, ultraviolet exposure and cigarette smoking. BCC most frequently affects the upper eyelids and involvement of the medial canthus is associated with a worse prognosis. These lesions are typically painless and very slow growing and may not be noticed by patients, especially those with poor vision. The lesions appear as a nodular ulcer with raised rolled borders (rodent ulcer). Lesions can be associated with surrounding skin changes including ectropion, entropion, dimpling of skin, and loss of eyelashes or madarosis. Due to the slow progression of these lesions, metastasis is rare. The diagnosis is made by excisional biopsy. The technique of Mohs’ micrographic surgery, the careful stepwise excision and microscopic monitoring of the surgical margins, produces a lower recurrence rate in addition to preserving the maximal amount of tissue.[7]

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the eyelid is 40 times less common than BCC, but it is much more aggressive. SCC most commonly occurs in the lower lid and can rapidly spread with local extension. Metastasis occurs in only 0.5% of SCCs that arise from sun-damaged skin, although metastasis may be more common in tumors that arise from chronically inflamed areas.[8] Lesions appear flat with overlying telangiectasia and scaling. As with BCC changes of the associated skin can be seen including ectropion, entropion, and madarosis. Surgical excision with wide margins and frozen sections is the treatment of choice due to the potentially deadly nature of this neoplasm.

Sebaceous cell carcinoma a highly malignant neoplasm arising from the eyelid lid sebaceous glands. Sebaceous cell carcinoma is found more often in the elderly and in women. It occurs two times more often in the upper lid as compared to the lower.[9] This lesion can masquerade as common benign lesions, so a high index of suspicion is critical. Chronic, unilateral blepharitis, recurrent chalazia and associated madarosis are highly suspicious signs of this disorder. A full-thickness eyelid biopsy with permanent sections is required for a correct diagnosis. These neoplasms can exhibit skip lesions and pagetoid spread making Mohs’ surgery risky. The prognosis of sebaceous cell carcinoma is worse than that of BCC or SCC, with a mortality rate of 20% secondary to metastasis.[10] Treatment includes wide excision with sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with high-risk features.

Secorrheic keratosis, actinic keratosis, and keratoacanthoma are examples of some common nonmalignant tumors on the eyelid. These require close follow-up and, frequently, excisional biopsy.

Blepharitis

Blepharitis is an extremely common condition characterized by anterior eyelid inflammation and posterior eyelid meibomian gland dysfunction. Clinically these entities lead to symptoms of burning, foreign body sensation, redness, mild itching, and tearing. These symptoms are frequently worse in the evening and are exacerbated by prolonged reading or wind exposure.

Blepharitis may be secondary to infectious or noninfectious causes. Organisms that inhabit the eyelids can also produce inflammation of the lids and cornea. The most common infectious cause of blepharitis is staphylococcus. Symptoms of staphylococcal blepharitis include collarettes, or material deposited at the base of the eyelashes, madarosis (lash loss), mild mucopurulent discharge, chronic conjunctivitis, and corneal changes. Treatment for staphylococcal blepharitis includes daily lid hygiene and topical antibiotics. Lid hygiene consists of scrubbing the eyelid margins with dilute baby shampoo or an over the counter commercial preparation. Warm compresses may then be applied to the lids with a clean washcloth. An antibiotic ointment, such as erythromycin or bacitracin, should be applied to the lids before bedtime for at least six weeks.

Noninfectious types of blepharitis include seborrheic blepharitis and meibomian gland dysfunction. Seborrheic blepharitis is characterized by oily lid margins, crusting of the lashes, conjunctivitis, and seborrheic dermatitis. Meibomian gland dysfunction is characterized by thickened irregular lid margins with inflammation around the orifices of the glands on the posterior eyelid surface. When expressed, the material within the glands may have a thick consistency. Acne rosacea has been associated. The treatment for noninfectious blepharitis includes lid hygiene, warm compresses, and systemic doxycycline.

Aqueous tear deficiency can additionally contribute to symptoms of dry eye in patients with blepharitis. These patients may be evaluated by examining the tear meniscus, tear breakup time, or a shortened interval between the blink and the separation of the tear film, and Schirmer testing, or a measure of tear production over a given period of time. Treatment of aqueous tear deficiency includes over the counter artificial tears, lubricating ointment at bedtime, and punctal occlusion.

Conjunctiva

Conjunctivitis affects all age groups; it is classified into acute or chronic and infectious or noninfectious subtypes. It does not cause structural damage to the eye except very rarely and with specific bacterial infections. Conjunctivitis typically presents with nonspecific symptoms such as irritation, discharge, photophobia, and itching. The conjunctiva is typically diffusely erythematous, and a slit-lamp examination may reveal follicular or papillary response.

Bacterial conjunctivitis is less common than viral conjunctivitis in adults and is characterized by copious mucopurulent discharge. Although bacterial, the disease is generally self-limited and symptoms resolve in two to seven days without treatment. Treatment may be started at presentation or at day three or four if symptoms are failing to resolve or worsening. Treatment includes topical broad-spectrum antibiotic agent such as a fluoroquinolone drop for five to seven days. The antibiotic regimen should be modified according to culture results. Any patient with neisseria infection should be followed daily and treated systemically with intravenous antibiotic therapy because of the potential rapid destructive clinical course.

Viral conjunctivitis is most commonly caused by adenovirus. Patients may have associated systemic symptoms of an upper respiratory tract infection. In contrast to bacterial infections, the discharge is more watery, but patients can have severe crusting of lashes in the morning. The disease is self-limited, lasting up to l0 days. Epidemic keratoconjunctivitis is a more virulent strain of adenoviral conjunctivitis. This syndrome is characterized by a highly contagious, rapidly spreading conjunctivitis commonly with preauricular lymphadenopathy, photophobia, and blurry vision. Viral conjunctivitis does not require and should not be treated with antibiotics. Therapies include aggressive use of lubricants and symptomatic relief with cool compresses. Severe cases may require topical steroids under the care of an ophthalmologist.

Allergic conjunctivitis is most often associated with symptoms of seasonal allergies and it is characterized by itching and a stringy, white discharge. The most effective treatment is environmental control of the offending allergen. As this not always possible, symptomatic treatment includes cold compresses and combined mast-cell stabilizer-antihistamine topical preparations. In severe cases, topical steroids can also be used under the care of an ophthalmologist.

Chronic conjunctivitis is defined as symptoms for greater than three weeks. The differential includes the systemic diseases of Chlamydia, molluscum contagiosum, conjunctival malignancy, ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, sebaceous cell carcinoma, eyelid malpositions, and irritation from medication drops such as glaucoma medications. If a neoplastic or cicatricial systemic process is suspected, a conjunctival biopsy should be performed.

Cornea

The cornea (Figure 39.1H) is the major refracting or focusing surface of the eye allowing transmission of light to the retina. The cornea consists of five layers: epithelium, Bowman’s layer, stroma, Descemet’s membrane, and endothelium. The endothelium functions as a metabolic pump containing Na + –K + ATPase transporting fluid out of the cornea to keep the optical system dehydrated and clear. The number of endothelial cells decreases with age but is unlikely to decrease to level at which corneal edema results. Corneal edema can occur with corneal dystrophies or secondary to trauma to endothelial cells during intraocular surgery.

Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy is a common cause of corneal edema in the elderly. Fuchs is characterized by corneal epithelial and stromal edema due to endothelial cell dysfunction and loss. This leads to the formation of guttata, or thickened areas of Descemet’s membrane due to stromal edema. These guttata can become pigmented and have a beaten bronze appearance. This condition is commonly bilateral, although it may be asymmetric. Patients are frequently asymptomatic until a significant amount of corneal edema accumulates causing symptoms of blurry vision that is worse in the morning and that clears throughout the day. This phenomenon is thought to be secondary to corneal dehydration associated with evaporation from the ocular surface throughout the day. As the condition progresses and more endothelial cell function is lost, epithelial edema or bullae may occur, causing pain. Early treatment strategies involve dehydrating the cornea with topical hyperosmotic agents. If corneal decomposition continues, these patients can go onto require corneal transplantation.

Trauma to the endothelial cells during intraocular surgery can cause a similar appearing pathology of corneal edema. Patients with low endothelial cell counts or corneal dystrophies are at a higher risk for this complication. Cataract surgery is the most commonly performed intraocular surgery in the United States. Corneal stromal edema following cataract surgery is termed pseudophakic bullous keratopathy. This condition can also be initially managed with hyperosmotic agents but often progresses to require a corneal transplantation.

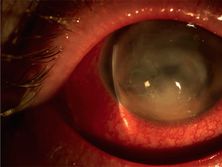

Decreased vision and pain along with acute onset red eye, pain, photophobia, and tearing can also signify infectious processes of the cornea (Figure 39.2). Contact lens wearers experience corneal infections at a much higher rate than the general population. Additionally, these patients are at risk for infection by highly virulent microbes including Pseudomonas and Acanthamoeba. Acanthamoeba is found in soil, swimming pools, hot tubs, and lake water and is resistant to freezing and the levels of chlorine routinely used. These patients commonly present with eye pain that is out of proportion to the appearance of the infectious process. Acanthamoeba infections can be devastating to the cornea, especially when diagnosis and treatment are delayed. Contact lens wearers with suspected infection should be urgently referred to an ophthalmologist. Infectious keratitis in non–contact lens wearers can be caused by a wide range of organisms. Staphylococcal infections can be associated with blepharitis as reviewed above and may lead to slowly progressive peripheral corneal infiltrates. In contrast, gram-negative bacterial infections such as neisseria progress rapidly and may lead to corneal perforation. Fungal keratitis is most common in southern climates and immunocompromised persons. Herpes simplex and varicella zoster infections can be mild and self-limited or may cause severe corneal infections with corneal anesthesia and scarring. Varicella zoster infections also produce pain and vesicular skin lesions in a dermatomal distribution.

Infectious keratitis; noted features include mattering of the eyelashes, injected conjunctiva, corneal haze, and hypopyon (anterior chamber collection of white blood cells).

The management of most corneal infections includes gram and giemsa stains of material obtained by scraping the bed of the ulcer, if present, as well as culture and sensitivity testing. Initial treatment may include frequent topical application of fortified broad-spectrum antibiotics and/or topical fluoroquinolone antibiotics. Modification of the treatment regimen is based on culture results and clinical response. Additional tests, such as confocal scanning, may be necessary to diagnose fungal or Acanthamoeba infections. Prolonged topical therapy is usually successful in clearing the infection, but surgical treatment may be necessary in cases with residual corneal scaring. Herpes simplex keratitis is generally treated with topical antiviral agents. Oral acyclovir may be helpful in treating and preventing recurrent keratitis. Acute varicella zoster infections are treated for 7–10 days with oral antivirals acyclovir 800 mg five times daily, famciclovir 500 mg three times daily, or valacyclovir 1 g three times daily to minimize ocular complications.[11] Steroids can rapidly exacerbate herpetic infections; thus, topical steroids should only be administered under the care of an ophthalmologist.

Presbyopia

Presbyopia is the most common ocular condition affecting the aging population. At approximately 40 years of age, people progressively lose the ability to accommodate, or focus on a near target. Normal accommodation is produced by ciliary muscle contraction, allowing relaxation of the zonules that hold the intraocular crystalline lens in place. This causes the crystalline lens to change shape and focusing power. Without the ability of the lens to adapt appropriately, patients need visual aids, usually in the form reading glasses or bifocals, to assist them in focusing on near targets.

Cataracts

An estimated 20.5 million Americans over the age of 40 have cataracts.[12] The prevalence increases to nearly 70% in Americans older than 75.[13] The natural crystalline lens is positioned behind the iris and supported by zonular fibers that arise from the internal layers of the eye (Figures 39.1K and 39.1L). It is composed of three layers. The zonular fibers are connected to a lens capsule and beneath the lens capsule is outer cortical layer of fibers and an inner nuclear layer. A cataract is an opacity in any of the three layers of the natural lens that that normally develops with aging. At present there are no therapies to prevent the formation of cataracts. (See Box 39.2.)

1. An estimated 70% of Americans over the age 75 have cataracts. Once the vision is unable to be corrected with a change in lens prescription, the patient may be offered cataract surgery based on an ophthalmologist’s evaluation.

Cataracts can vary in appearance dependent on which layer of lens the opacity is located. Opacity in the nuclear layer is known as nuclear sclerosis. Nuclear sclerosis occurs as the number and density of lens fibers increases over time. Initially this thickening of the natural lens may cause a shift in the focusing power of the eye allowing the patient to read without glasses. Vision continues to decline as the lens progressively thickens and yellows eventually requiring surgical removal to restore vision. Cortical cataracts are opacities in the cortical layer of the natural lens. They often appear spoke-shaped and impair vision to varying degrees. Posterior subcapsular cataracts are opacities just anterior to the posterior capsule of the natural lens. Visual impairment and glare symptoms are found in bright light with both cortical and posterior subcapsular cataracts.

There are systemic conditions that have been found to increase and accelerate the presentation of cataracts. In particular, diabetes mellitus is associated with early onset and a higher incidence of cataracts. Large osmotic shifts, such as those occurring in hyperglycemic episodes, lead to the formation of cataracts due to swelling of the lens fibers. Blunt trauma, electrical shock or ionizing radiation has also been found to cause cataract formation. Lastly many drugs have been linked to cataract progression including long-term topical or systemic corticosteroids, chlorpromazine, amiodarone, and phenothiazides.

Nonsurgical management of cataracts entails accurate refraction and eyeglass correction. Eventually, the vision does not improve significantly with a change in lens prescription and the patient may be offered cataract surgery based on an ophthalmologist’s evaluation.

Cataract surgery

Recent technological advances in cataract surgery have been extraordinary. Extracapsular cataract extraction and phacoemulsification are microsurgical techniques that remove the cataract and leave the posterior lens capsule intact so that an intraocular lens may be implanted in the native lens capsule. Most recently, ophthalmic lasers have been introduced into the market to assist in cataract extraction. Intraocular lens implants are small disc-shaped pieces of polymethylmethacrylate, acrylic, silicone, or hydrogel that are manufactured with differing powers. The power of the implant is determined by the optical properties of each patient’s eye, which is measured pre-operatively. Cataract surgery is an outpatient procedure, the majority being done under local anesthetic and mild intravenous sedation. Ideally, following cataract surgery distance glasses are not required because refractive error is taken into account with intraocular lens power selection. However, most patients will require reading glasses for near vision following cataract surgery; multifocal and accommodative intraocular lens are gaining favor to allow patients to see clearly at all distances without glasses. Visual acuity following cataract surgery is 20/40 or better in 97% of patients without coexisting ocular pathology. Patients have significant improvement in their quality of life and overall visual function, such as nighttime and daytime driving, community and home activities, mental health, and life satisfaction.[14]

The most common complication is opacification of the posterior lens capsule occurring in approximately 20%–30% of patients. The posterior capsular opacification can be cleared with an in-office laser procedure. Retinal detachment is one of the more serious sequelae following cataract surgery with a lifetime incidence of 0.7%. Cystoid macular edema following cataract surgery may cause temporary and sometimes permanent visual impairment. Cystoid macular edema is characterized by intraretinal edema. Patients present with a gradual loss in central vision most commonly occurring 6–l0 weeks postoperatively. Approximately, 75% cases improve without intervention. Topical steroids and NSAIDS may be useful in cases that do not spontaneously improve. More rare, but sight threatening complications of cataract surgery include intraocular lens dislocation, endophthalmitis, and expulsive choroidal hemorrhage.

Bacterial endophthalmitis is a true emergency and one of the most feared complications of intraocular surgery. This most commonly occurs within two weeks of the surgery. Less than 1 in 1,000 surgeries are complicated by acute bacterial endophthalmitis.[15] The most common organism implicated is staphylococcus epidermis. Patients typically present with acute eye pain and loss of vision. Anterior chamber inflammation may be associated with a hypopyon, or layered leukocytes. Emergent referral to an ophthalmologist is necessary if this condition is suspected. Surgical removal of the infected vitreous body with instillation of intravitreal antibiotics and steroids has been reported to be successful in treating this condition.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree