| Clinical findings | % |

|---|---|

| Fever | 85%–90% |

| Right upper quadrant pain | 84%–90% |

| Hepatomegaly | 30%–50% |

| Weight loss | 33%–50% |

| Diarrhea | 20%–33% |

| Cough | 10%–30% |

| WBC count >12 000/μL | 80% |

| Elevated level of alkaline phosphatase | 70% |

Approximately 80% of the liver abscesses are found in the right lobe of the liver, thus explaining the location of pain. The pain may also be located in the epigastrium, right lower chest, or the right shoulder tip (referred pain). Left-sided abdominal pain, corresponding to an abscess in the left lobe of the liver, is less common. Localized swelling or generalized hepatomegaly may be noted on exam depending on the size and location of the abscess or abscesses. Abscesses high in the right lobe of the liver may not result in hepatomegaly but, if of significant size, can lead to elevation of the right hemidiaphragm, which is evident on a chest radiograph.

Laboratory findings in a patient with amebic liver disease include leukocytosis (white blood cell [WBC] count >12 000/mm3), an elevated alkaline phosphatase, and, occasionally, elevated transaminases. It is uncommon to see an elevated bilirubin, and thus jaundice in a febrile patient with right upper quadrant pain should point the clinician toward another diagnosis. A mild degree of anemia (anemia of chronic disease) is present in many cases, particularly with symptoms for more than 2 weeks.

Diagnosis

Aspiration of a liver abscess is usually only indicated to rule out a pyogenic abscess or to prevent potential rupture as described below. Thus, the diagnosis of an amebic liver abscess is made in a patient with appropriate clinical symptoms, epidemiologic risk factors, and characteristic imaging findings confirmed by a positive serologic, antigen, or molecular test. Serologic testing for antibodies to E. histolytica is >80% sensitive in disease more than 1 week old, and nearly 99% sensitive in recovering patients. A negative test essentially rules out the diagnosis except in early infection (≤1 week). It is important to use an enzyme immunoassay (EIA) or agar gel dilution to test serology as an indirect hemagglutination often remains positive for years at high titer, and residents of an endemic region may have positive antibodies to E. histolytica that do not represent acute disease. Serum antigen detection tests to the E. histolytica Gal/GalNAc lectin gave a positive result in >95% of patients with amebic liver abscess in a study in Bangladeshi patients prior to treatment, comparing favorably to currently available serum antibody tests. Importantly, after treatment with metronidazole, circulating antigen levels were rarely detected (15%), making the test potentially useful for the diagnosis of acute disease in endemic countries. Molecular diagnosis using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays are highly sensitive and specific but remain primarily a research tool for the near future.

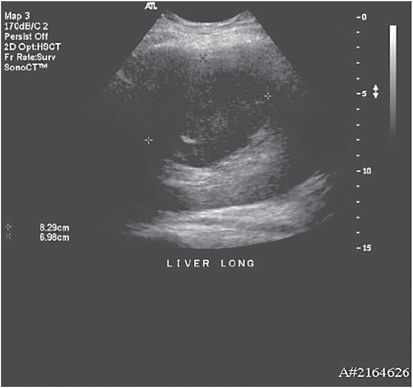

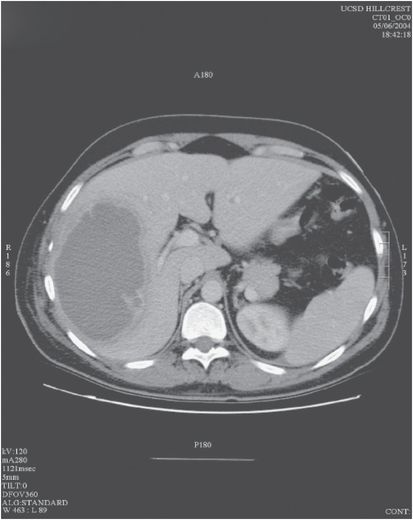

A number of imaging modalities are useful in supporting the diagnosis of amebic liver abscess. Chest radiographs in approximately 50% of patients with liver abscesses demonstrate an elevated right hemidiaphragm or other abnormality such as discoid atelectasis. Ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT) scanning, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are all quite sensitive; however, the availability of these studies in amebiasis endemic areas is often limited. In the majority of cases, imaging demonstrates a single round or oval, homogeneous, hypoechoic lesion. Low-attenuation lesions with septations or an observable fluid level or debris may also be seen (see Figures 204.1 and 204.2). Unfortunately, although gallbladder and ductal abnormalities are seen more often in pyogenic liver abscess, there are really no specific radiographic features distinguishing pyogenic from amebic liver abscesses; therefore, imaging only serves as an aid to confirming the clinical suspicion of an intrahepatic process.

Figure 204.1 Contrast computed tomography (CT) scan image of an amebic liver abscess. The abscess appears as a hypoattenuating mass within the right lobe of the liver with an irregular, multiseptated rim with a thin rim of surrounding edema.

Aspiration of a liver abscess for the purpose of diagnosis is not generally recommended except in cases where immediate exclusion of a pyogenic abscess is clinically warranted. The classic gastronomic description of amebic pus as “anchovy paste” or “chocolate sauce” refers to the thick, acellular, proteinaceous debris consisting of necrotic hepatocytes and few polymorphonuclear cells obtained by successful aspiration. Amebic trophozoites are magenta colored by periodic acid–Schiff staining, making them easy to visualize, but finding trophozoites in an aspirate only occurs in 20% to 30% of cases, with a higher yield from the edge of the abscess.

The differential diagnosis of amebic liver abscesses includes pyogenic abscess, hepatocellular carcinoma, especially with necrosis, and echinococcal cyst. On imaging, the differential can often be narrowed to pyogenic abscess versus amebic liver abscess, with the clinical and radiographic findings being largely indistinguishable. Some epidemiologic differences may help to increase the likelihood of pyogenic liver abscess: age >50 years old, no sex predominance, underlying diabetes mellitus, biliary disease, and lack of travel to an endemic country. Nevertheless, these clues do not rule out amebic liver abscess, especially in a patient living in an endemic country.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree