Evaluation and Rehabilitation of Speech, Voice, and Swallowing Functions After Treatment of Head and Neck Cancer

Jan S. Lewin

Katherine A. Hutcheson

“Few other cancers demonstrate the need for anticipatory treatment and rehabilitation to the magnitude required in the management of head and neck cancer.”

—Myers, Barofsky, and Yates, 1986.1

Head and neck cancer often results in significant functional changes including alterations in or loss of human voice, disruptions in speech production, and deterioration of swallowing ability. These problems can occur as the result of the disease as well as the primary treatment, whether surgery, radiation therapy (RT), or both. Adjuvant treatments that include RT generally increase functional deficits. A thorough understanding of the functional effects associated with the given treatment modality or combination of modalities is essential and must be conveyed adequately to the patient as the patient’s choice of treatment modality and their compliance with therapy often depend on functional restoration. A multidisciplinary team approach and ongoing communication among clinicians is critical to successful rehabilitation and optimal speech, voice, and swallowing outcomes.

Experience has shown that patients with head and neck cancer express similar concerns and functional goals. What seems to be most important to patients is to avoid a stoma, to speak with laryngeal voice, to eat and drink by mouth, and to avoid the use of adaptive equipment for either speech or swallowing. In a multicenter study, speaking abilities ranked as the primary contributor to psychosocial outcomes and quality of life after treatment for head and neck cancer followed by swallowing function.2

OVERVIEW OF SPEECH AND SWALLOWING IMPAIRMENTS

Speech, voice, and swallowing are highly complex processes that depend on a series of precisely coordinated biomechanical events and physiologic interactions of the oral, pharyngeal, and laryngeal anatomy. Oropharyngeal anatomy and movement are the key determinants of speech intelligibility, vocal resonance, and swallowing competency. Therefore, any alteration in structure or physiology, such as those that result from head and neck cancer, will ultimately affect aerodigestive tract functioning.

EVALUATION OF SPEECH, VOICE, AND SWALLOWING

Pretreatment Evaluation

Rehabilitation, more specifically its planning, should begin at the time of diagnosis with patient counseling and a thorough baseline evaluation provided by a speech pathologist who is an expert in the management of functional disorders associated with head and neck malignancies. For many patients, the need for speech and swallowing treatment is unexpected and, therefore, difficult for the patient to accept. Fears and misconceptions associated with cancer treatment and its outcomes are often alleviated by providing realistic expectations for recovery and discussing the rehabilitative options that are available to the patient for functional restoration. Subsequent understanding and acceptance often leads to better follow through with the cancer treatment and rehabilitation.

Pretreatment evaluation establishes a baseline of speech and swallowing ability for appropriate treatment planning and posttreatment comparison. The plan for posttreatment rehabilitation, which should be based on both clinical and objective measures of examination, will depend on the site of the disease and the type of cancer treatment selected.

Swallowing Evaluation

The act of swallowing includes the oral preparatory, oral, pharyngeal, and esophageal stages. The oropharyngeal swallow consists of the first three stages only, which include all events occurring from the lips to the upper esophageal sphincter (UES). It is the oropharyngeal swallow that is most often affected by head and neck cancer.

Speech pathologists evaluate and treat oropharyngeal swallowing disorders. Unlike esophageal swallowing problems, disorders of the oral preparatory, oral, and pharyngeal stages of the swallow can be treated with functional interventions such as changes in posture and exercises that strengthen and increase the range of motion of muscles involved in the act of swallowing.

Gastroenterologists generally manage esophageal causes of dysphagia, such as esophageal stricture, for which the main treatment is dilation.

Gastroenterologists generally manage esophageal causes of dysphagia, such as esophageal stricture, for which the main treatment is dilation.

Oral tongue control and strength are important to ensure efficient movement during mastication and posterior propulsion of foods and liquids to the pharynx. Regardless of the type of cancer treatment, surgical or nonsurgical, the primary correlates of pharyngeal swallowing proficiency are tongue base retraction, pharyngeal contraction, and laryngeal elevation and anterior excursion.3 Tongue base retraction and pharyngeal contraction act as the driving force to move the food through the pharynx, whereas hyolaryngeal excursion is essential to open the cricopharyngeus and deflect the epiglottis downward for airway protection. The ability of the true vocal folds (TVFs) to completely close is important but not essential to airway protection and functional swallowing. For example, patients with unilateral TVF paralysis often compensate for glottic incompetency by using other mechanisms of airway closure to safely swallow without aspirating; therefore, safe swallowing is not solely dependent on TVF closure. Thus, procedures that augment the TVFs to improve airway closure and reestablish subglottic pressure may help swallowing but may not always prevent aspiration if the dysphagia etiology includes more than impaired glottic closure. Therefore, the results from objective instrumental examinations should clearly define the etiology of the aspiration to help guide rehabilitation and avoid the use of techniques, surgical or otherwise, that are not indicated or useful in remediating the dysphagia.

The assessment of swallowing competency relies on comprehensive examination including patient interview, clinical observation, and physiologic findings from instrumental examinations. The clinical or bedside swallowing examination allows observation of important events in the oral stage of swallowing, including labial and lingual control, adequate clearance of food from the oral cavity after the swallow, and oral sensitivity. However, the clinical swallowing evaluation is not reliable to diagnose pharyngeal swallowing disorders because clinicians must infer problems that occur during the pharyngeal stage. Despite this limitation, the examiner can detect signs and symptoms suggestive of pharyngeal swallowing problems. A well-trained clinician synthesizes overt as well as subtle observations from the clinical or bedside examination and uses this knowledge to make recommendations including the need for further objective swallowing assessments.

The need for objective, instrumental swallowing evaluation in patients with head and neck cancer cannot be overemphasized. Instrumental evaluation is essential because swallowing physiology cannot be reliably inferred from subjective patient reports.4 For example, patients may report no problems swallowing when in fact, they are actually silently, without coughing or exhibiting any other indication, aspirating what they swallow. In studies of patients with advanced laryngeal cancer, aspiration has been reported as high as 36% in unselected samples with rates up to 82% in patients who complain of dysphagia. More concerning are the data that show between 36% and 80% of patients who aspirate do so silently.5,6,7 In fact, as many as 60% of patients with head and neck cancer have speech and/or swallowing impairments but may not fully perceive them.8

The most widely used instrumental swallowing evaluations are the modified barium swallow (MBS) study and the fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES). The choice of either test usually depends on the type of swallowing problem and the ability of the patient to undergo a radiologic procedure. In any case, an instrumental examination, MBS, and/or FEES should be used for any patient with head and neck cancer and/or who is at risk for swallowing problems or aspiration.

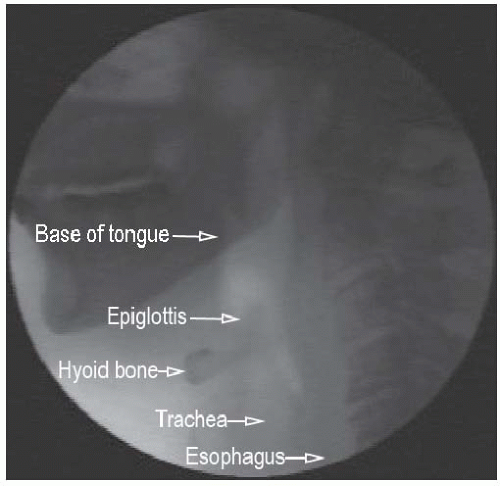

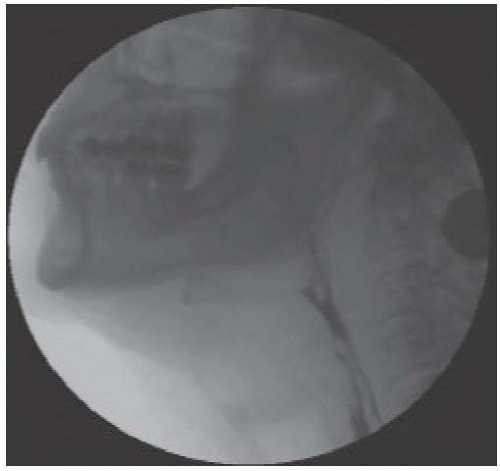

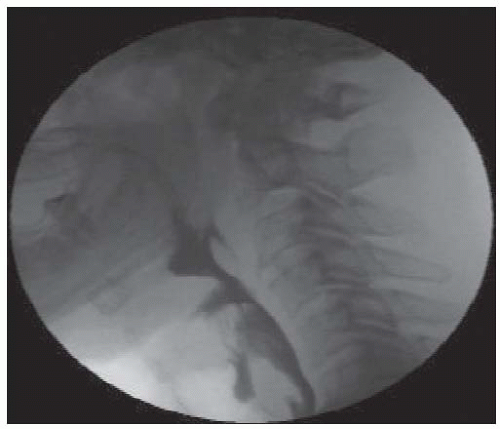

The MBS study is generally most preferred for assessing the oropharyngeal swallow. It allows the examiner to radiographically assess all three stages of the oropharyngeal swallow, from the point at which the food is placed in the mouth to the time it enters the cervical esophagus. The MBS study is performed jointly by a speech pathologist and a radiologist. The swallowing assessment should include the use of radiopaque liquids, pastes, and solids because swallowing physiology will vary according to the consistency and amount of food. This is in contrast to the traditional barium swallow study or esophagram, the primary purpose of which is to evaluate the structural integrity of the esophagus and identify aspiration while a large liquid bolus is continuously swallowed. The barium esophagram is not the evaluation of choice for examining oropharyngeal swallowing physiology as the results do not provide the information necessary to differentially diagnose oropharyngeal swallowing disorders and the causes of aspiration. In contrast, the primary purpose of the MBS study is to obtain information that is essential to understanding oropharyngeal swallowing physiology. An additional benefit of the MBS examination is the ability to immediately assess the usefulness of selected compensatory swallowing strategies to relieve the dysphagia. Therapeutic recommendations are made on the basis of the physiologic findings shown on the MBS study. Figure 11-1 shows the normal oropharyngeal anatomy viewed laterally on an MBS study. Figure 11-2 shows a normal swallow viewed laterally on an MBS, and Figure 11-3 shows an abnormal swallow with aspiration.

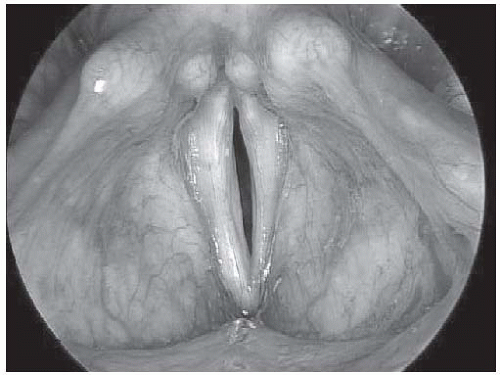

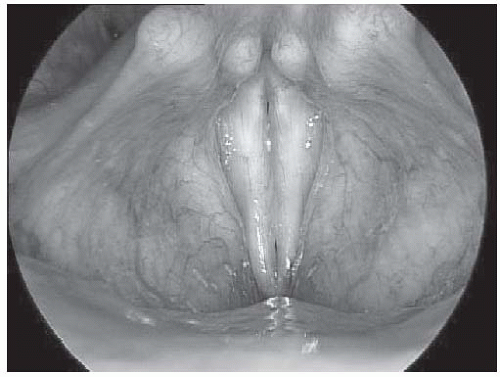

Alternatively, FEES uses a flexible endoscope placed transnasally to examine the pharyngeal swallow while providing direct visualization of laryngeal anatomy. The main advantages of FEES are that it does not expose the patient to radiation and that it can be easily performed as a clinical procedure for patients who cannot tolerate or are not candidates for the MBS study. FEES has been shown to be equivalent to the MBS study in its ability to detect aspiration.9 It is a particularly excellent examination for patients who have larynx cancer because it provides the best view of glottic competency, including airway protection and vocal fold mobility. Unlike the MBS study, FEES can be paired with sensory testing to help determine laryngeal sensitivity.10

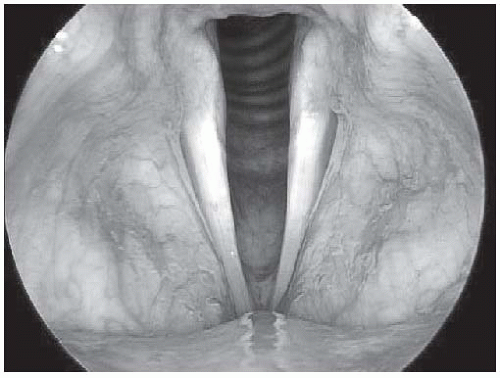

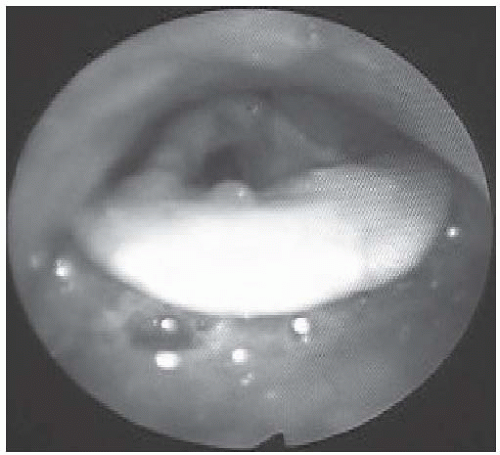

The primary disadvantages of FEES are its inability to visualize the oral preparatory and oral phases of the swallow and the period of “white-out” that occurs at the onset of the pharyngeal stage of swallowing that obscures visualization during peak of deglutition. Therefore, because all oral phase disorders as well as some pharyngeal disorders of swallowing must be inferred, the usefulness of FEES is more limited in patients with tumors of the oral cavity and oropharynx. However, like the MBS study, FEES provides critical feedback regarding the effectiveness of swallowing compensations and strategies. FEES is also useful in its ability to provide the patient with immediate biofeedback and visualization during therapy sessions. Figure 11-4 demonstrates FEES with food residue in the pharynx after the swallow has occurred.

Voice Evaluation

Voice evaluation should assess the perceptual, vibratory, acoustic, and aerodynamic parameters of voice production. A comprehensive evaluation should at a minimum include assessment of the fundamental frequency of sound production, the ability to vary pitch and intensity, phonatory duration, and properties of airflow, air pressure, and glottal resistance.

FIGURE 11-4. Fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES) with food residue in the pharynx and on the laryngeal surface of the epiglottis after the swallow. |

Laryngeal videostroboscopy provides a critical assessment of patients with head and neck cancer and vocal abnormalities. Videostroboscopic assessment employs the use of an endoscope that uses a straight and pulsed light source to assess vocal fold movement and vibration. Like FEES, videostroboscopy can be performed as an office procedure. This examination provides valuable information regarding vocal fold vibration as well as an immediate and magnified image of the presence or absence of laryngeal pathology that is often undetectable using standard methods of indirect laryngoscopy. The clinician can observe patterns of TVF approximation, symmetry and regularity of motion, and the presence of mucosal wave that will be affected by laryngeal disease and its treatment. Videostroboscopy is an essential component of the physical examination of patients with head and neck cancer and provides a permanent record for documentation and comparison of laryngeal functioning over the course of treatment. Videostroboscopic results are illustrated in Figures 11-5, 11-6, and 11-7.

Speech Evaluation

Speech evaluation generally encompasses the administration of a combination of perceptual measures of articulation and speech intelligibility that include examination of the rate of speech, articulatory precision, and intelligibility in single words, phrases, and conversation. Formal test batteries that have been standardized on targeted populations provide an objective appraisal of speech production that can be used for comparison over time. A combination of formal and perceptual measures of speech production and a physical examination of the structures of the oral cavity and their patterns of movement are the most useful tools for differentially diagnosing speech disorders and planning effective treatment.

The findings from a thorough speech assessment are also critical to other members of the multidisciplinary rehabilitation

team. Information regarding articulation and vocal resonance assists maxillofacial prosthodontists in determining candidacy for and manufacturing of palatal augmentation prostheses, obturators, and lifts for patients with defects of the oral cavity and soft palate. Additionally, information regarding speech articulation and intelligibility helps plastic surgeons select reconstructive procedures and techniques that will optimize cosmetic and functional outcomes.

team. Information regarding articulation and vocal resonance assists maxillofacial prosthodontists in determining candidacy for and manufacturing of palatal augmentation prostheses, obturators, and lifts for patients with defects of the oral cavity and soft palate. Additionally, information regarding speech articulation and intelligibility helps plastic surgeons select reconstructive procedures and techniques that will optimize cosmetic and functional outcomes.

REHABILITATION AFTER SURGICAL RESECTION

Any surgery that resects critical structures of the upper aerodigestive tract and disrupts oropharyngeal physiology will result in problems with both speech and swallowing. The functional disability that occurs after head and neck surgery is usually proportional to the volume and site of resection. The correlates of dysfunction depend on the site of lesion and include oral tongue mobility, base of tongue retraction, pharyngeal motility, glottic closure, and laryngeal excursion.3 The rehabilitative focus varies depending on the type of surgery and reconstruction. For example, patients who undergo glossectomy will require both speech and swallowing rehabilitation to improve speech intelligibility and facilitate the return to oral alimentation. Alternatively, the focus of rehabilitation after total laryngectomy is usually to restore voice or sound production.

After Oral Cavity Resection

The size and location of the tumor, extent of surgery, and type of reconstruction greatly impact functional outcomes after oral cavity resection. Because the tongue is a fundamental structure to both speech and swallowing, the degree of dysfunction often correlates with the extent and location of tongue resection. Studies have shown that resections of the tongue base and anterior tongue are associated with significant functional deficits.8 Despite the importance of the oral tongue, data clearly show that the tongue base remains the most essential lingual region for normal swallowing.3 Even after a total resection of the oral tongue, a patient can learn to swallow safely as long as the base of the tongue is preserved and continues to function.

Reconstructive procedures for oral cavity defects are often challenging because they require sufficient tissue to preserve function while avoiding overcorrection with tissue bulk that obstructs adequate speech and swallowing. Reconstructions of the oral cavity should aim to preserve mobility, shape, and volume of remaining structures and prevent pooling of secretions and food. Resections of the oral cavity that preserve sensorimotor innervation in combination with reconstructions that allow residual tongue mobility generally result in better speech and swallowing function. The degree of functional impairment often depends on the quality rather than the extent of the reconstruction; experience has shown that some patients who have undergone total glossectomy swallow better than patients who have undergone partial resections that use bulky flap reconstructions or those that tether the tongue.

In addition to the importance of the tongue during the oral phase of swallowing, the tongue plays a critical role during the pharyngeal phase of swallowing. Oral cavity resections may impact oral transit and control and consequently affect the ability to elicit a safe pharyngeal swallow. There is an increased risk for aspiration as resections of the oral cavity become larger and more extensive and interfere with oropharyngeal physiology. In particular, patients whose surgeries affect the suprahyoid musculature may aspirate because of the disruption to the elevation and anterior tilting action of the larynx, which is needed to protect

the airway during swallowing. Thus, the ability to spare adjacent musculature, such as the suprahyoid elevators, is an attractive feature of transoral endoscopic surgical approaches.

the airway during swallowing. Thus, the ability to spare adjacent musculature, such as the suprahyoid elevators, is an attractive feature of transoral endoscopic surgical approaches.

In addition to swallowing, resections that affect critical structures and physiology of the oral cavity will also affect speech production and intelligibility. The severity of speech and swallowing dysfunction usually parallel each other. The mechanisms for articulatory compensations may include exaggeration of remaining labial, jaw, dental, pharyngeal, and laryngeal movements. Surgical alterations of the tongue and oral cavity can also change the characteristics of vocal tract resonance such as pitch, nasality, and vocal quality by changing the shape and vibrating properties of the vocal tract.

Most patients are able to achieve understandable speech and some degree of oral nutrition after adequate postoperative healing and rehabilitation. A recent systematic review suggests that speech remains largely intelligible (sentence level: 92% to 98% intelligibility) for a majority of surgically treated patients with advanced-stage oral cancer, including those with involvement of the tongue. However, deviant speech characteristics such as abnormal articulation were reported in most cases despite intelligible speech ratings.11

After oral cavity resections, a variety of rehabilitative techniques are used to maximize speech and swallowing function that may include targeted exercise regimens, articulatory compensations, postural adjustments, swallowing maneuvers, or the use of adaptive equipment. The selection of the appropriate intervention should be based on a thorough examination of functional deficits. Again, multidisciplinary interaction and communication cannot be overemphasized. This is particularly true for patients who require palatal prostheses after oral cavity resections that include the hard palate and/or tongue. For these defects, the speech pathologist and maxillofacial prosthodontist work together to fabricate a prosthesis that is tailored to the patient’s individual needs.

Hard palate resections that result in oronasal fistulas are usually addressed at the time of surgery with a prosthetic obturator. However, patients who also require partial resection of the soft palate cannot be easily obturated due to the dynamic nature of the residual soft palate and are therefore more difficult to rehabilitate than patients who have undergone total soft palate resection. As is the case for patients with hard palate resections, our experience shows that patients who have undergone total soft palate resection and who are adequately obturated usually speak and swallow without difficulty.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree