Dix-Hallpike maneuver (right ear).[25] The patient is seated and positioned so that the head will extend over the top edge of the table when supine. The head is turned 45° toward the ear being tested (position A). The patient is quickly lowered into the supine position with the head extending about 30° below the horizontal (position B). The patient’s head is held in this position, and the examiner observes the patient’s eyes for nystagmus. In this case with the right side being tested, the physician should expect to see a fast-phase counter-clockwise nystagmus. To complete the maneuver, the patient is returned to the seated position (position A) and the eyes are observed for reversal nystagmus, in this case a fast-phase clockwise nystagmus.

Spontaneous EVS (episodes lacking a clear, reproducible trigger) may occur with reflex presyncope, vestibular migraine, Menière’s disease, and panic disorder. The diagnosis may be straightforward when the underlying condition is accompanied by typical features or accompanying symptoms, such as headache with vestibular migraine or fear and palpitations with panic disorder. In the absence of discriminating features, one must be careful to consider transient ischemic attacks, cardiac arrhythmias without palpitations, and hypoglycemia. If chest pain, dyspnea, or syncope is associated with a spontaneous episode, then a cardiovascular cause or pulmonary embolus is more likely than a neurological cause. Furthermore, it is important to note (and not widely recognized) that cardiac causes may produce spinning-type vertigo.[14] Similarly, TIA may present with dizziness or vertigo in the absence of neurological signs in 10%–20% of individuals before proceeding to major stroke.[13] Therefore, a high index of suspicion is necessary when encountering recurring, spontaneous EVS, particularly if the symptoms are new in the prior six months and the frequency of attacks is increasing.

As noted earlier, it is important to differentiate truly episodic symptoms (brief episodes separated by asymptomatic intervals) from dizziness that is persistent but exacerbated by intolerance for head movement or dizziness that his always present with standing or walking in patient with unsteadiness.

Treatment

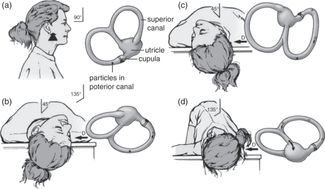

Patients with BPPV usually benefit from physical maneuvers to reposition canal otoliths (Figure 9.2).[15] Dizziness typically lasts only seconds and becomes progressively less intense with each episode. Antihistamines are not helpful in BPPV and may produce side effects, including drowsiness, that increase the risk of falls. Vestibular migraine is probably more common than previously imagined; treatment is generally by a combination of lifestyle modification and prophylactic medication.[16]

Particle repositioning maneuver (right ear): schema of patient and concurrent movement of posterior/superior semicircular canals and utricle.[25] The patient is seated on a table as viewed from the right side (A); (B)–(D) show the sequential head and body positions of a patient lying down as viewed from the top. Before moving the patient into position B, turn the head 45° to the side being treated (in this case it would be the right side): patient is in normal Dix-Hallpike head-hanging position (B). Particles gravitate in an ampullofugal direction and induce utriculofugal cupular displacement and subsequent counter-clockwise rotatory nystagmus. This position is maintained for 1–2 minutes. The patient’s head is then rotated toward the opposite side with the neck in full extension through position C and into position D in a steady motion by rolling the patient onto the opposite lateral side. The change from position B to D should take no longer than 3–5 seconds. Particles continue gravitating in an ampullofugal direction through the common crus into the utricle. The patient’s eyes are immediately observed for nystagmus. Position D is maintained for another 1–2 minutes, and then the patient sits back up to position A. (D) = direction of view of labyrinth, dark circle = position of particle conglomerate, open circle = previous position.

Acute, continuous episodes of dizziness lasting days to weeks

Acute Vestibular Syndrome (AVS) is characterized by acute, continuous dizziness or vertigo lasting days to weeks associated with nausea or vomiting, intolerance to head movement, and gait unsteadiness. Nystagmus is typically present at the time of symptoms, although sometimes it is partially suppressed by normal vision, making it more difficult to detect. During an attack, most patients seek help in an emergency department or urgent care setting. Uncommonly, bouts of AVS may occur as part of a relapsing and remitting illness (usually multiple sclerosis) that results in chronic residual dizziness. Accurate assessment of the “timing” characteristic depends on recognition of continuous symptoms over days to weeks, unlike EVS, which consists of brief episodes lasting seconds to hours even if they recur over days or weeks. When symptoms are present at the time of assessment, a physical exam can be useful for localizing the cause (e.g., focal neurological deficits, otitis media, or herpes zoster rash of Ramsey-Hunt syndrome). It is important to note, however, that a provocative test such as the Dix-Hallpike maneuver used to detect posterior semicircular canal otoliths will predictably exacerbate dizziness in an AVS patient who is experiencing head movement intolerance, and this exacerbating feature is commonly misinterpreted as a trigger. Likewise, the history may reveal a toxic drug exposure (i.e., phenytoin or gentamicin) or head trauma. One must be careful not to prematurely ascribe AVS to a peripheral labyrinth disorder as a result of exposure to a recent viral upper respiratory infection before an appropriate evaluation has excluded dangerous causes such as stroke.

In acute, continuous dizziness, patients will feel worse when their head is moved, but this exacerbating feature has no diagnostic value. All AVS patients, whether due to stroke or vestibular neuritis, will feel worse when moved. Do not perform the Dix-Hallpike test in these patients.

Differential diagnosis

It is critical when a patient presents with AVS to differentiate between urgent and less urgent causes. An abridged differential diagnosis is provided in Table 9.2. Head trauma and medication are the most common exposures causing AVS. When the onset of AVS is spontaneous (i.e., lacking an obvious antecedent exposure), then acute unilateral peripheral vestibular neuritis (dizziness or vertigo only) or labyrinthitis (dizziness or vertigo with hearing loss) is likely. However, vestibular neuritis and labyrinthitis are diagnoses of exclusion, and stroke (particularly of the posterior fossa) can mimic either very closely. Note that focal neurologic signs and symptoms may be absent in approximately 80% of patients with stroke presenting with AVS.[17] Computed tomography (CT) has extremely low sensitivity (16%) for acute ischemic stroke,[18] so unless the patient has severe headache, lethargy, or hemiparesis (signs of cerebellar hemorrhage), CT should not be performed when imaging is required.[19] Magnetic resonance (MRI) with diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) misses approximately 15%–20% in the first 24 to 48 hours after onset of continuous symptoms, but it is our current gold standard test when obtained from 72 hours to seven days.[20] When encountering a patient with isolated AVS, strong evidence indicates that a careful eye exam (HINTS to INFARCT) outperforms MRI in ruling out stroke (Table 9.3).[20, 21] A central stroke, usually in the posterior fossa, is very likely when the patient has any one of three dangerous eye movement signs: (1) normal head impulse test of the vestibular ocular reflex, (2) fast-phase alternating nystagmus, or (3) vertical ocular misalignment (i.e., vertical skew deviation of eyes). Note that, paradoxically, a normal head impulse test is not good (that is normal, in the context of AVS, supports stroke).

In contrast, vestibular neuritis without hearing loss is likely when the bedside head impulse test of the vestibular ocular reflex is abnormal; there is predominantly horizontal, “direction-fixed” nystagmus consistently beating the opposite direction of the head impulse abnormality, regardless of the gaze position; and there is normal ocular vertical alignment with alternating cover test (absence of skew). Presence of all three findings has a tenfold greater power to rule out stroke than early MRI (negative likelihood ratio of 0.02 (CI: 0.01–0.09) vs. 0.21 (CI: 0.16 – 0.26).[22] Although this approach is now well validated in expert hands, it has not been tested when applied by nonspecialists. New portable video-oculography devices may eventually make testing for these signs in primary or urgent care more readily available.[23]

In acute, continuous dizziness, eye movement exams (HINTS) outperform our current gold standard, MRI, to look for ischemic stroke. New devices may eventually make it easier for primary care physicians to test these eye movements. Do not bother with CT unless a rare case of cerebellar hemorrhage is suspected.

Treatment

After stroke or other dangerous causes are ruled out, young patients with AVS due to vestibular neuritis and labyrinthitis are often able to be sent home from the emergency department with medication to suppress nausea and dizziness. Frail older adults, by contrast, may require hospitalization to ensure that symptoms are controlled and hydration is maintained.

Chronic dizziness lasting from months to years

Many older adults have chronic vestibular syndrome (CVS). This category of dizziness is usually related to a chronic, progressive neurological or vestibular condition with pathological findings that are present at the time of examination that often suggest the diagnosis. Symptoms may be stable or progressive over months to years, even though they may fluctuate in severity over time. Dizziness is often context dependent, such as when the patient reports feeling dizzy only or always when walking. This should not be interpreted as “episodic” or as “triggered” by an upright posture. Because dizziness typically develops gradually with the progression of the underlying neurological or vestibular condition, patients most often seek evaluation in an outpatient setting.

In the elderly, common causes of CVS that are associated with unsteadiness are sensory peripheral neuropathy (e.g., diabetes, B12 and thyroid deficiency) and dizziness related to the gait disorder resulting from Parkinson’s disease, degenerative joint disease of the lower extremities with instability, or dementia. Other causes are listed in Table 9.4. A thorough assessment of the patient includes bedside examination of musculoskeletal function and testing for upper motor neuron and extrapyramidal motor abnormalities; autonomic system dysfunction; peripheral sensory abnormalities; and vestibular, ocular, and cerebellar impairment. Depending on the patient’s general health and preferences, neuroimaging may be indicated to rule out treatable conditions such as hydrocephalus.