| Fungi |

|---|

| Candida species (especially C. albicans) |

| Aspergillus species |

| Histoplasma capsulatum |

| Blastomyces dermatitidis |

| Viruses |

|---|

| Herpes simplex virus type 1 |

| Cytomegalovirus |

| Varicella-zoster virus |

| Human immunodeficiency virus Human papilloma virus |

| Bacteria |

|---|

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis and M. avium |

| Actinomyces israelii |

| Staphylococcus aureus |

| Streptococcus viridans |

| Lactobacillus acidophilus |

| Treponema pallidum |

| Idiopathic ulcerative esophagitis in AIDS |

| Parasite |

|---|

| Trypanosoma cruzi |

Fungal infections of the esophagus

Candida species

Candida albicans is the fungal organism most frequently implicated in infectious esophagitis. Other Candida species (Candida tropicalis, Candida parapsilosis, Candida krusei, and Candida glabrata) less commonly cause disease in the absence of severe immunosuppression. Candida organisms are normal components of the oral flora, and colonization of the esophagus is not unusual. A population-based study revealed esophageal colonization in approximately 20% of healthy, ambulatory adults. Colonization involves adherence and proliferation of Candida organisms within the superficial mucosa. Progression to infectious esophagitis requires invasion of the epithelium, usually in the setting of defective cellular immunity. The spectrum of esophageal infection with Candida species is broad, ranging from scattered white plaques accompanied by mild or no symptoms to dense pseudomembranes consisting of fungi, sloughed mucosal cells, and fibrin overlying severely damaged mucosa. The latter are usually accompanied by severe symptoms.

Advanced infection with HIV is the most significant risk factor for the development of candidal esophagitis, although the prevalence of esophageal Candida infection is decreasing with the widespread use of HAART. Infection is primarily seen with CD4 counts <200/mm3 and represents an AIDS-defining illness. The risk of infection increases with the degree of immune compromise, occurring most frequently in patients with persistently low CD4 counts. Additional risk factors include hematologic malignancies, diabetes mellitus, adrenal insufficiency, alcoholism, advanced age, radiation therapy (especially for cancers of the head and neck), systemic chemotherapy, and the use of topical oro-nasopharyngeal steroids. Esophageal motility disorders (e.g., achalasia) may also predispose to infection. Immunosuppression in organ transplant recipients imparts significant risk although the prevalence of infection is reduced by the frequent use of systemic fungal prophylactic therapy. Immunomodulatory and biologic therapy, increasingly utilized in the management of immunologic conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid arthritis, does not appear to increase the risk for esophageal candidiasis.

Clinical presentation and complications

Candida esophagitis may not cause symptoms, particularly in those who are immunocompetent with few adherent esophageal plaques. When symptomatic, the most common complaint is odynophagia, usually localized to a discrete retrosternal area. Odynophagia may impair swallowing minimally, or the pain may be so intense that the patient avoids eating (sitophobia) and is unable to tolerate secretions. In severe cases, retrosternal chest pain or burning may be present without swallowing. In granulocytopenic patients, fungal infection may be disseminated, thereby resulting in fever, sepsis, and signs and symptoms related to hepatic, splenic, or renal fungal abscesses.

In AIDS, esophageal candidiasis is commonly associated with oropharyngeal thrush. However, Candida esophagitis occurs independently of thrush at least 25% of the time. Overall, positive and negative predictive values of thrush for diagnosing Candida esophagitis are 90% and 82%, respectively.

It is important to recognize that mucosal Candida infections frequently coexist with other esophageal infections. For example, in published case series, oral thrush was present in 7 of 14 patients with herpes simplex virus (HSV) esophagitis and in 2 of 10 with HIV-associated idiopathic ulcers. In a study including 52 HIV-infected patients diagnosed with symptomatic Candida esophagitis, concomitant cytomegalovirus (CMV) and HSV infections were found in 22 and 2 patients, respectively.

Severe complications of esophageal candidiasis include esophageal bleeding from ulceration; luminal obstruction from a fungus ball; mucosal scarring and stricture; fistulization into the trachea, bronchi, or mediastinum; and esophageal mucosal sloughing with replacement by pseudomembranes. Although life-threatening hemorrhage has been reported, bleeding from esophageal candidiasis is usually mild, not requiring transfusion.

Diagnosis

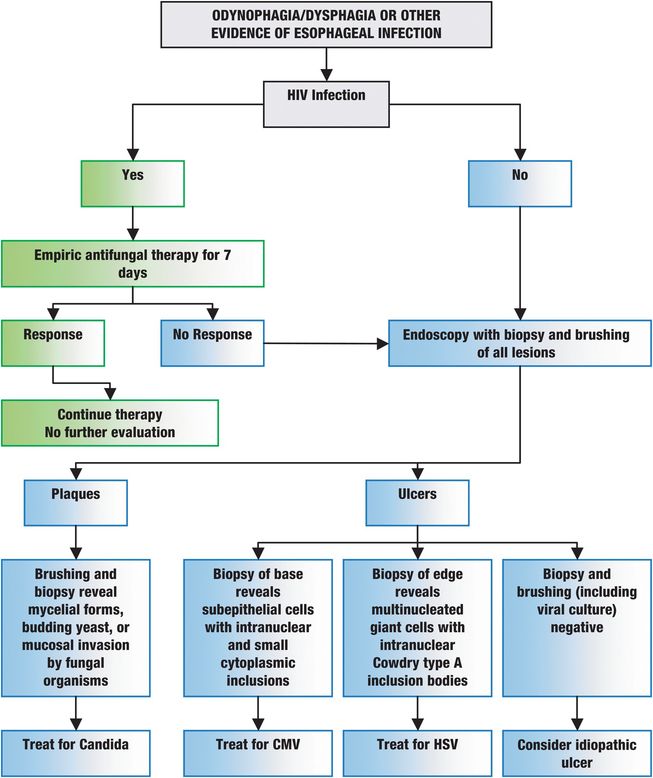

Candida esophagitis should be suspected when at-risk patients complain of odynophagia or dysphagia. In this setting, empiric therapy is recommended, as uncomplicated cases should improve within several days. However, because of frequent coinfection, further evaluation (e.g., esophagoscopy) is appropriate for those not responding within 3 to 4 days.

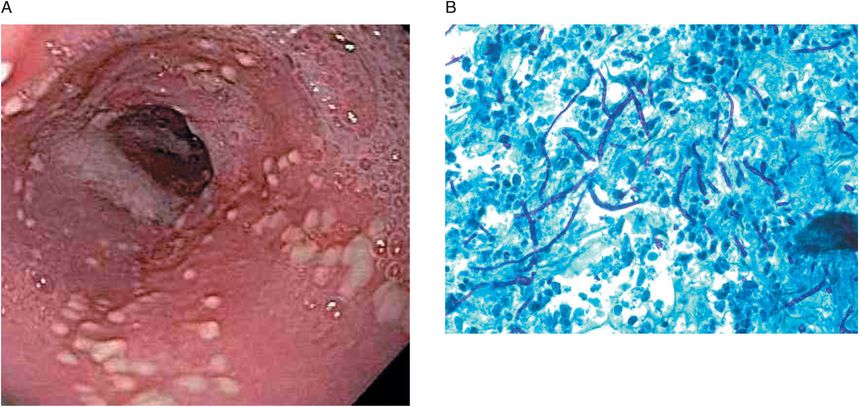

The most accurate method for diagnosing fungal esophagitis is endoscopy with directed brushing and biopsy of lesions (Figure 48.1). Endoscopic appearance alone may be suggestive but is insufficient to diagnose Candida esophagitis. Typical candidal plaques are creamy white or pale yellow (Figure 48.2A). Brushings from involved surfaces and ulcers can be obtained with a sheathed cytology brush spread onto slides and stained by the periodic acid–Schiff (PAS), silver, or Gram methods. Mycelial forms and masses of budding yeast are consistent with Candida infection (Figure 48.2B). Fungal cultures are generally not helpful unless an unusual pathogen (e.g., a resistant Candida species, such as C. glabrata) is suspected.

Figure 48.1 Suggested diagnostic approaches to common esophageal infections. HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; CMV = cytomegalovirus; HSV = herpes simplex virus type 1.

Figure 48.2 (A) Endoscopic appearance of Candida esophagitis with multiple raised white plaques. (B) Biopsy revealing budding yeast cells, hyphae, pseudohyphae, and mucosal invasion by the organisms (periodic acid–Schiff 60×; courtesy of Harris Yfantis, MD, Baltimore VA Medical Center, MD).

Because findings are often nonspecific and concomitant infections will be missed, radiographic studies of the esophagus are not primarily utilized to diagnose esophageal infections. Radiographic examination may be useful when endoscopy is not available, when biopsies are contraindicated because of coagulopathy, or when perforation, stricture, or fistula is suspected (significant dysphagia or coughing with eating). When abnormal, barium esophograms may reveal a “shaggy” esophagus, plaques, pseudomembranes, cobblestoning, nodules, strictures, fistulas, or mucosal bridges.

Treatment

Guidelines published by the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) support the general approach that Candida esophagitis requires systemic therapy and should not be managed with local agents. High-risk patients with odynophagia or dysphagia can be treated empirically with oral antifungal therapy without endoscopic confirmation of disease, particularly if oral thrush is present. If symptoms do not improve after 3 to 4 days, further evaluation is necessary.

Antifungal treatment options for esophageal candidiasis include the imidazoles, echinocandins, and amphotericin B. Imidazoles alter fungal cell membrane permeability by inhibiting ergosterol synthesis. Potential agents in the imidazole class include fluconazole, itraconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole. Fluconazole (400 mg loading dose followed by 200 to 400 mg daily for 14 to 21 days orally or intravenously) is favored due to its excellent efficacy (as high as 90%), ease of administration, infrequent toxicity, and low cost. Itraconazole oral solution (200 mg daily) appears as effective as fluconazole in randomized trials but can be limited by associated nausea. Itraconazole capsules are available, but absorption may be unpredictable compared to the solution. Additionally, itraconazole inhibits the cytochrome P450 enzymes, increasing the potential for drug interactions. In a large, randomized, double-blind, multicenter trial, voriconazole (200 mg twice daily orally or 4 mg/kg every 12 hours intravenously) was as effective as fluconazole and may be effective in cases refractory to fluconazole. Posaconazole oral solution (400 mg twice daily) has likewise shown efficacy in itraconazole- or fluconazole-refractory Candida esophagitis. Echinocandins inhibit the synthesis of β(1,3)-D-glucan, an essential component of Candida cell walls. Options include caspofungin, micafungin, and anidulafungin. The echinocandins are administered intravenously and are therefore utilized in hospitalized patients with severe Candida esophagitis. In addition, echinocandins are associated with higher relapse rates and cost more than azoles, so they are generally reserved for azole-refractory or -intolerant cases. In a double-blind, randomized trial of patients with advanced HIV and confirmed Candida esophagitis, caspofungin (50 mg daily intravenously) was efficacious and well tolerated compared to fluconazole (200 mg daily intravenously). Caspofungin also appears effective in fluconazole-resistant cases, and provides an attractive alternative to the more toxic amphotericin B. Studies with micafungin (150 mg daily intravenously) and anidulafungin (100 mg on day 1 followed by 50 mg daily intravenously) also suggest similar initial efficacy and tolerability compared to fluconazole. However, higher relapse rates were seen with anidulafungin than with fluconazole, and the current recommended treatment dose is 200 mg daily intravenously.

Amphotericin B binds irreversibly to fungal membrane sterols, thereby altering membrane permeability. Amphotericin B (0.3 to 0.7 mg/kg daily intravenously) has similar efficacy compared to fluconazole but, due to increased toxicity relative to other agents, its use should be limited in patients with Candida esophagitis. Current indications for amphotericin B include infections associated with drug resistance and pregnancy. Imidazoles are teratogenic and should not be used during the first trimester of pregnancy. No data are available regarding the use of echinocandins in pregnancy.

Of the different types of agents used for treating esophageal candidiasis, drug resistance has been associated predominantly with imidazoles. Risk factors include advanced immunosuppression and chronic imidazole exposure, regardless of whether continuous or episodic. Resistant cases can usually be managed with the echinocandins or amphotericin B.

For chronically

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree