Ageing and Chronic Disease Epidemiology

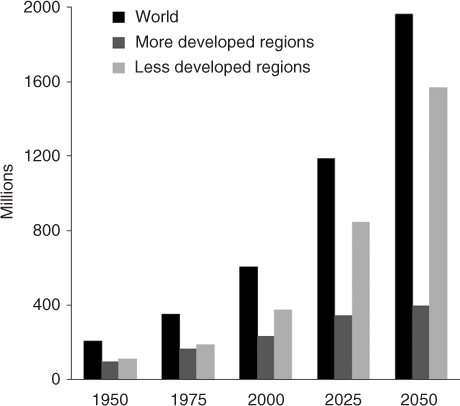

According to the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs’ 2002 report, World Population Ageing: 1950–2050,1 the number of older adults has tripled in the last 50 years and is expected to again triple over the next 60 years. This unprecedented population shift is a consequence of steep declines in both fertility and mortality. The percentage of the population aged 60 years and over will equal that of individuals younger than 15 years by 2050 because of the projected decline in birth rates. This population shift is profound. In some developed countries, older persons already far outnumber children. Although the rate of these changes and subgroup proportions vary by region of the world, all regions are experiencing increasing longevity (Figure 6.1). The most rapidly growing group world-wide is those 80 years of age and over. The speed of the demographic transformations is unprecedented. For example, this seminal report1 has revealed that 66% of the global increase in the world occurred in less developed areas over the last half century. The result of these demographic changes will culminate in four-fifths of the world’s older population living in the less developed regions of the world.

Figure 6.1 Expansion of the population aged 60 years and over: world and development regions, 1950–2050.1

In the United States, population projections indicate that one in five people will be aged 65 years or over by 2030.2 According to these figures, between 2025 and 2030 the population aged over 60 years will be growing 3.5 times more rapidly than the total population. According to figures from the National Service Framework for Older People3 in England, the number of people over 65 years old has more than doubled since the early 1930s, resulting in one-fifth of the population in England being comprised of persons over 60 years of age. Also, between 1995 and 2025, it is projected that the number of people over the age of 80 years will increase by 50% and the number of people aged over 90 years will double.

The public health significance of these demographic transformations includes the increased burden of chronic disease and disability on health care and socioeconomic impacts on care giving. The focus of health care must be related to reductions in age-specific disability and comorbidities. Current data based on the United States Vital Statistics show that heart disease and cancer are the top two leading causes of death for whites, blacks, American Indians/Alaska Natives, Asian/Pacific Islanders and Hispanics.4 This is followed by chronic lower respiratory disease, stroke, diabetes, influenza and pneumonia (Table 6.1). However, these rates vary by racial and ethnic group. Life expectancy at the age of 65 years in 2006 was 17 years for men and 19.7 years for women, an increase of 1 and 0.7 years, respectively, since 2000. Diabetes is increasing in prevalence in older men and women. Men have a higher rate of both diagnosed and undiagnosed diabetes at 26% versus 24% for women. In addition, the rate of diabetes among those aged 65 years and over increased over three times faster among non-Hispanic black men. Although the prevalence of heart disease appears unchanged in the last decade, men continue to be diagnosed and suffer from heart attacks at a higher rate than women (Table 6.2). Non-Hispanic white males have the highest prevalence of diagnosed heart disease in the United States.

Table 6.1 The leading causes of death in the United States in 2006.41.

1. Heart disease: 631 636 2. Cancer: 559 888 3. Stroke (cerebrovascular diseases): 137 119 4. Chronic lower respiratory diseases: 124 583 5. Accidents (unintentional injuries): 121 599 6. Diabetes: 72 449 7. Alzheimer’s disease: 72 432 8. Influenza and pneumonia: 56 326 9. Nephritis, nephrotic syndrome and nephrosis: 45 344 10. Septicaemia: 34 234 |

Table 6.2 European Union—Eurostat data: circulatory disease/cancer (two-thirds of deaths).

| Circulatory diseases (heart attacks, strokes and other circulatory diseases) |

| 41% of all deaths |

| 42% of all deaths for 65–84-year-olds |

| Cancer |

| 25% of all deaths |

| Highest cause of mortality for 45–64-year-olds |

World Population Ageing: 1950–20501 describes the total dependency ratio as a measure of potential social support needs. Therefore, dependency can be used as a proxy for disability in older adults. Dependency ratios offer important information about the relative impact of ageing on the world’s population. The ratio between the dependent population (both young and old persons requiring support) is projected to shift, with the older population constituting an almost equal component of dependency with the younger population and even to rise to 63% of the total dependency ratio in developed regions by 2050. The importance of these numbers is that health care needs to address risk factors of disability in the ageing to stem the burden of dependency.

The response to population ageing needs to focus on the identification of risk factors and the development of effective prevention and treatments for disability. An additional focus is shortening the period of disability in the ageing population. As Hubert et al. noted,5 the approach should be similar to reduction in cardiovascular incidence rates: risk factor models are identified from epidemiologic data and interventions are developed focusing on modifiable or reversible factors. Increased dependency equates to increased care taking and financial burden on families and increased institutionalization of older persons. Therefore, addressing the needs and interventions that accompany disability is rooted in targeted research. Longitudinal studies offer insight into associations of risk factors with disability.

The study of ageing and related diseases has been gradual and has occurred in response to changing population demographics. In the United States, the National Institutes of Health established one of its 27 Institutes and Centers as a National Institute of Ageing in 1974. This signalled interest and support for initiatives in ageing research.6 In addition, many programs in gerontology and geriatrics were established. The consequence of these developments has been new studies pertaining to various aspects of ageing and geriatric research emerging as an important focus of interest. Population-based health studies around the world have taken initiatives to include older people in data collection and analysis. Prospective longitudinal studies will be important in advancing research and health services for chronic disease and disability that affects older persons. The ultimate goal of these activities is to increase disability-free years and improve quality of life. Therefore, a shift will be necessary to study not only mortality risks, but also risks and modifiable aspects of disability related to disease. Cooperative research that occurs through programs such as EU Public Health Programme and the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) are examples of important sources of data on ageing that can be used to advance aforementioned aims.

Epidemiological research is an important step in developing prevention strategies and creating recommendations and guidelines specific for older adults. In addition to epidemiologic knowledge, clinical studies and judgment along with patient preferences conjointly contribute to evidence-based medicine (see Figure 6.2).

Disability and Ageing

Disability Types

Because disability often complicates and accompanies ageing, it is an ever-present consideration affecting decision-making in geriatric medicine. Disability can be especially burdensome for women, those residing in poverty and minorities. The ability to distinguish the types or trajectory of disability is an important focus of health sciences research. These issues are also imperative for assessing the need for services and economic appropriation for health care services. Several studies have provided useful data on the prevalence, incidence and changes associated with disability.

The type of disability most often associated with older persons is physical loss of function. Physical losses are usually measured by the ability to accomplish activities of daily living (ADLs), instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) and functional limitations. According to the European Health Expectancy Monitoring Unit7 (EHEMU) calculations from SHARE, women live over half of their projected life expectancy at the age of 65 years with one or two conditions or morbidities. The conditions or morbidities include heart disease, hypertension, high cholesterol, cerebrovascular disease/stroke, diabetes/elevated blood glucose, chronic lung disease, asthma, arthritis, cancer/malignant tumour, stomach/duodenal ulcer, peptic ulcer, Parkinson’s disease, cataract and hip fracture. Although this list is long, it is notable for including five of the leading causes of death noted in Table 6.1. Also, these figures should be examined in the light of the longer life expectancy of women. According to the EHEMU’s 2006 report,7 women appear to experience poorer physical functional health than men and spend considerably less time, 27% compared with 45%, after 65 years of age without physical limitations. Also, 20% of expected years at age 65 years, for both men and women, are spent with severe limitations.

The US National Center for Health Statistics8 analysed data from the 2001–2007 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) conducted on a non-institutionalized United States population and noted an increasing incidence of age-associated physical limitation. In this sample of 238 018 people aged 50 years and over from the Sample Adult component of the NHIS, persons’ physical limitations were assessed by eight separate questions reflecting difficulties with certain activities because of health problems. Individuals aged 80 years and older are 2.5 times more likely to have one or more limitations than individuals aged 50–59 years. Moreover, the percentage of United States adults with three or more physical limitations also increases from 8% to 27% in individuals aged 80 years and older. Sociodemographic differences were found and indicated that the greatest differences in physical limitations exist between non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic blacks and men and women. Higher rates are also seen in adults with less than 12 years of education. Overall, these results indicate a significant increase in self-reported disability related to age, race and gender. It is also important to recognize that self-reported disability is important to individual quality of life.

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES I) and the NHANES I Epidemiologic Follow-up study examined risk factors for disability in 4428 50 to 77-year-old participants.5 This study showed that the most important baseline predictors of physical disability at 10 year follow-up were age, non-recreational activity level, history of arthritis, education, female gender and weight for height at age 40 years. Similarly, a study of 1741 University of Pennsylvania alumni between the ages of 63 and 72 years showed a postponement of disability by 7.75 years in those who exercised, had a normal body mass index and did not smoke.9

A chronic disease associated with multiple forms of disability in older persons is diabetes. Diabetes is a leading cause of death and by its associations with cardiovascular, neurological and ophthalmologic diseases has a significant impact on disability in the elderly. Approximately one-quarter of older men and women had diabetes in the United States in the period 2003–2006.4 In a study of diabetic individuals aged 60 years and older from the NHANES III study, 32% of women and 15% of men reported physical limitations in walking, climbing stairs and housework compared with 14 and 8% of women and men, respectively, without diabetes.10 As such, diabetes represents a chronic illness that makes a substantial contribution to disability in older populations.

The Lifestyle and Independence for Elders Pilot Study (LIFE-P),11 a multicentre randomized clinical trial of individuals with functional limitations, found that adherence to a moderate-intensity physical activity intervention over 12 months showed a significant improvement in the Short Physical Performance Battery when participants performed ≥150 min per week of the activity. This trial indicates that physical activity interventions for previously sedentary older adults are possible and do result in measurable improvements in outcomes. This is significant because of the previously noted risks for disability with non-recreational inactivity and exercise specifically indicated in postponement of disability.

The focus of risk assessment and reduction for physical disability should occur in individuals over the age of 80 years, women, non-Caucasians, overweight/obese persons and those with less than 12 years of education. Additionally, preventive measures for disability, such as exercise, should not be limited to those without any disability. Comorbid diseases such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes should be assessed as a contributor to the disability burden in older adults. Prior disability is also significantly associated with the development of disability in activities of daily living.12

Mental disability often accompanies physical disability in ageing. Mental disability can be classified as major depression, dementia and vascular-related cognitive disorders. Dementia is the major contributor to mental disability because it is also associated with other mental and behavioural disturbances such as depression, anxiety and psychosis. Stroke, one of the leading causes of death and a significant contributor to the development of vascular dementia, is an important contributor to disability. Risk factors for both stroke and dementia are important targets for interventions that can decrease disability. Longitudinal studies on dementia and stroke are important stepping stones to discovering the impact and interventions. The 1987–1996 Kungsholmen Project is a longitudinal population-based study of 776 home-dwelling subjects aged 75 years and older in Stockholm, Sweden.13 Thus far, this study has generated findings on the impact of social networks on the development of dementia. Wang et al.13 suggested that frequent participation in mental, social and productive activity is associated with a lower risk of dementia in the elderly.

An unfortunate and all too common result of ageing is the loss of social ties due to death and their own or other’s physical or mental disability. In addition, changing dynamics of family structure and migration contribute to this isolation. Social isolation should be recognized as a factor in an individual’s overall health and quality of life. Social isolation can be considered a disability that occurs with ageing. This is an important consideration in the institutional placement of the elderly. Deciding whether placement will decrease or increase social isolation is an important consideration. Social isolation speaks of the importance of quality of life in making decisions. For example, placement of an elderly widowed male with multiple medical problems may result in loss of contact with social networks with friends and family, but may also provide a new source of social interactions.

Another type of disability is sensory disability, which includes limitations due to hearing or vision loss. These losses can often lead to deepening social isolation. The limitations can result in increased needs for an individual, medication management, special telephone service and transportation needs. These added needs represent a burden to the patient economically and psychologically. The extent of the disability can be determined by a specialist, audiologist, optometrist, or ophthalmologist. The impact that the disability has on the patient’s life is what the medical professionals, for example physicians, nurses, social workers, therapists and transportation specialists, need to determine.

A specific type of sensory disability is presbycusis, sensorineural hearing loss, which can occur among older persons and may go undiagnosed and untreated. This high-frequency hearing loss with difficulty in speech discrimination often leads to further social isolation of older adults. According to the National Institutes of Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), 18% of American adults 45–64 years old, 30% of adults 65–74 years old and 47% of adults 75 years old or older have a hearing impairment. In addition, the NIDCD notes that 12.3% of male and nearly 14% of female adults aged 65 years and older in the United States are affected by tinnitus. Evaluations by both an otolaryngologist and audiologist are useful for determining possible causes of hearing loss and hearing aid utility.

Self-reported hearing loss and deafness have been evaluated in a number of studies. For example, the National Center for Health Statistics in the United States in 2003 found that approximately 600 000 or 0.22% of the population self-report as deaf, with more than half being over the age of 65 years. A study of the prevalence of hearing loss in a cohort of 48–92-year-olds, with an average age of 65.8 years, was 45.9%, with mild hearing loss in 58.1%, moderate loss in 30.6% and marked loss in 11.3%.14

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree