46 End-of-Life Care and Other Ethical Issues

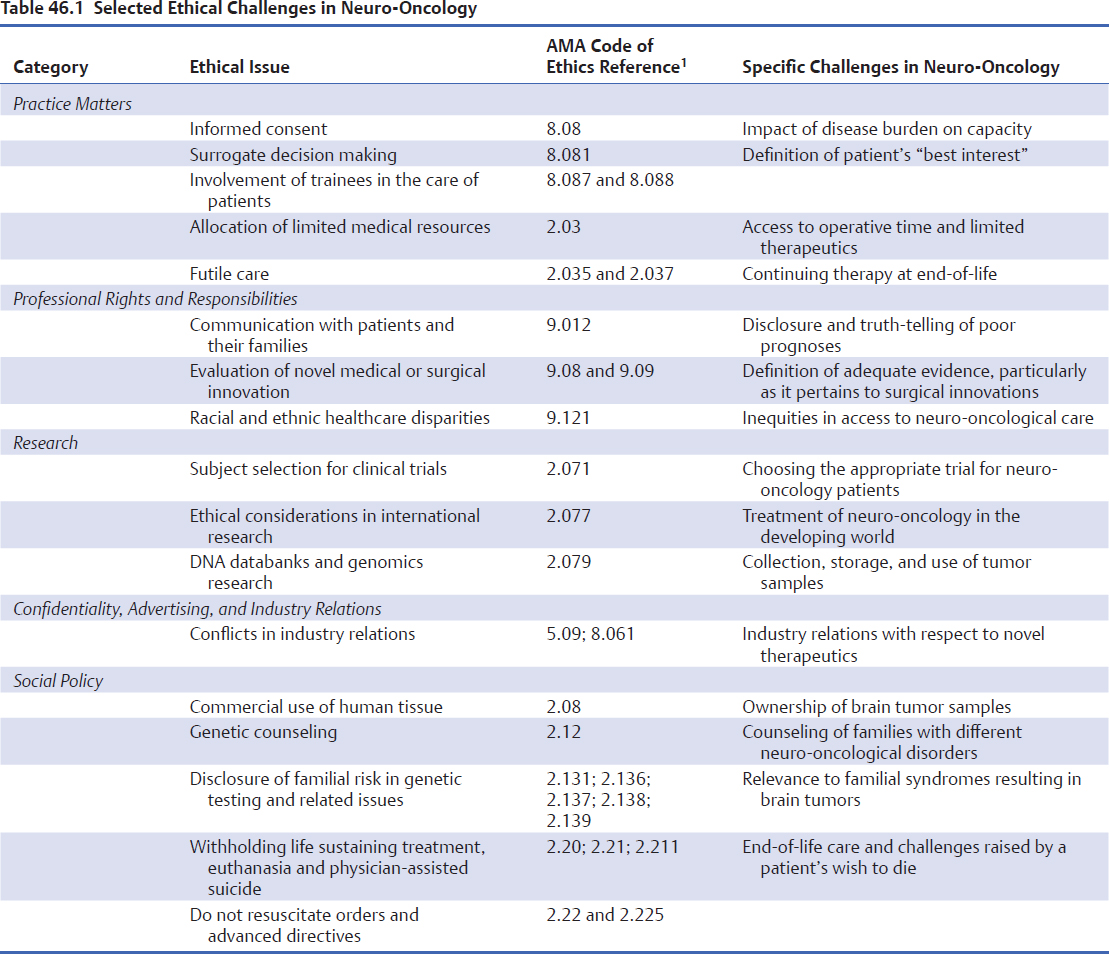

The evolving field of neuro-oncology is replete with ethical and moral challenges that permeate virtually every aspect of patient care. In the disclosure of the diagnosis and prognosis, the initiation of standard and experimental therapies, the evaluation of patients’ quality-of-life during treatment, and the initiation of end-of-life care, clinicians often face complex dilemmas that they must resolve by making difficult decisions. In contrast to law and policy, which dictate what “must” and “tends to” be done, respectively, ethics describe a set of values, principles, and beliefs that guide decisions that “should” be made (Fig. 46.1). Although various tools and guidelines, such as the American Medical Association (AMA) Code of Ethics,1 are available to inform the decision-making process, the management of patients with neuro-oncological diagnoses may present unique ethical challenges (Table 46.1). The multifaceted ethical dilemmas encountered in the care of these patients have, in fact, considerably advanced the discipline of medical bioethics.

Individuals affected by brain tumors and other neuro-oncological diagnoses represent an especially vulnerable patient population due to the devastating disease burden, as well as the effects of the underlying pathology on patient capacity, agency, and identity. Ethical dilemmas are also introduced in clinicians’ attempts to balance duties to current and future patients while conducting clinical research. Furthermore, the nascent field of cancer genetics and the emerging practice of biobanking have generated increasing questions regarding the clinician’s conflicting role as both a medical provider and scientific investigator, and about privacy of patients’ information. Given the prevalence of ethical conflicts in neuro-oncology, basic knowledge of ethical principles and theory is essential for the provision of care to affected individuals.

This chapter is an introduction to bioethical fundamentals that are salient in the care of patients with neuro-oncological diagnoses. The four classic principles of medical bioethics are respect for autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice. Autonomy refers to the patient’s inalienable right to self-determination, whereby any intervention requires the voluntary informed consent of a capable person without undue influence or coercion. Beneficence and nonmaleficence relate to the clinician’s obligation to serve the best interest of the patient while first doing no harm. Justice refers to the equitable treatment of neuro-oncology patients, affording them the same opportunities as other patients.

Pearl

• The four primary principles of medical bioethics are respect for autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice.

Special Consideration

• Neuroethics is an emerging field that recognizes the unique nature of the brain as the substrate of agency, capacity, and identity.

Increasingly, clinicians and ethicists alike are also acknowledging the uniqueness of ethical challenges arising from the effects of pathological conditions on the brain, which serves as the seat of consciousness and the substrate of identity and capacity. The burgeoning field of neuroethics aims to study ethical, legal, and societal issues related to brain function and its impairment.

This chapter also explores ethical issues in the conduct of neuro-oncology research and thus can serve as a resource for clinicians throughout their interactions with patients, from diagnosis to treatment, recruitment into research studies, and during end-of-life care.

Diagnosis: Disclosure and Truth-Telling

Diagnosis: Disclosure and Truth-Telling

Receiving the diagnosis of a central nervous system neoplasm is a distressing turning point in a patient’s life.2 Adjustment to the diagnosis of a brain tumor is highly individual process that may be affected by demographic and psychosocial factors.3 Patients often view brain cancers as a unique group of neoplasms as a result of the value placed on cognitive function and mental capacity.4

There has been a paradigm shift in the disclosure of neuro-oncological diagnoses in Western culture. Historically, clinicians have been reluctant to disclose the full extent of brain tumor diagnoses and prognoses for various reasons, including perceived patient vulnerability or lack of understanding.5 In 1961, 90% of physicians did not reveal a cancer diagnosis to patients,6 but by 1979 only 2% reported that they would withhold such information.7 With the widespread availability and accessibility of information, patients are now also increasingly empowered to play an active role in directing their medical treatment. The dissemination of medical knowledge through online venues and an increasing departure from the paternalistic model of health care has enabled patients to serve as the primary stakeholders in their own care.8

Disclosure of the cancer diagnosis is necessary to protect the patient’s right to self-determination, that is, to enable individuals to make informed decisions regarding their care that are consistent with their own goals. Importantly, the patients themselves have consistently emphasized the necessity of honesty and candid disclosure during their care.9 It has been previously suggested that having a sense of control over their treatment plans may provide patients with a sense of hope and optimism.10 Furthermore, disclosure of the neuro-oncological diagnosis and expected prognosis enables patients to have realistic expectations regarding the likely outcomes and, if relevant, facilitates preparation for the process of dying. These goals cannot be overemphasized, considering that advanced cancer patients have previously been shown to overestimate their likelihood of long-term survival and often falsely believed that the purpose of offering multiple treatment options was to maximize the chances of cure.11,12

Pitfall

• Withholding information may be viewed as a form of deception, which may adversely impact the physician–patient relationship.

Special Consideration

• A “relational” view of autonomy holds that the patient’s internal moderating factors must be considered during disclosure of information.

To navigate their illness, patients also depend on the physician–patient relationship. Such relationships are nearly universally asymmetric with greater vulnerability on the side of patient.5 The concept of trust is therefore central in establishing an effective therapeutic interaction. The withholding of information regarding the diagnosis or prognosis may be viewed as a form of deception.13 Although most patients trust their physicians to make decisions in their best interest, even subtle forms of deception are viewed as unacceptable.14 Truth telling is, therefore, a process at the center of the physician– patient relationship, which aims to empowering patients to navigate their disease course.5

The argument for full disclosure of the diagnosis and prognosis, however, may prioritize autonomy and the right to self-determination over other ethical principles. A traditional view of autonomy holds that capable individuals may make all necessary decisions regarding their personal care when equipped with all options, alternatives, and perceived benefits and risks. Practically speaking, there is considerably heterogeneity in the degree to which patients desire to be informed of their condition. It is also self-evident that different individuals may prioritize different treatment options, even when presented with the same information. Freedom of choice may be affected by cultural, social, and personal considerations, even when all the information is rationally presented to patients.5 A “relational” view of autonomy has been proposed, whereby special consideration must be paid to patients’ internal moderating factors that may affect their autonomy.15,16 These may include preoperative levels of stress, willingness to participate in the decision-making process, and level of understanding of the information presented.

Management: Clinical Care, Research, and Therapeutic Misconception

Management: Clinical Care, Research, and Therapeutic Misconception

Initiation of Nonexperimental Therapy

The patient’s decision to undergo treatment, whether medical or surgical, is highly individualized and often guided by the physician’s duty to maximize benefit and reduce harm. In some circumstances, there is equipoise between different therapeutic options and it remains to the patient to choose which treatments to undertake. One example of this is the decision to undergo resection or biopsy for presumed low-grade glioma as opposed to the watch-and-wait approach. It has been shown that, in such situations, the decision to undergo surgery is moderated by the disease burden, quality of life, and fear of morbidity from the intervention as well as trust in the treating physician.17

In most cases, however, varying levels of evidence may support one treatment strategy over another and thus inform the options presented to patients. Most patients with brain tumors undergo surgery, and the majority of those with malignant neoplasms also receive chemotherapy and radiation therapy.18 Informed consent for treatment requires adequate disclosure to a capable patient in the absence of any undue influence.19 Although fully informed consent may not be feasible, given that numerous unforeseen risks may be later encountered,20 physicians have an obligation to disclose common and material risks to patients. As defined in the landmark litigation of Canterbury v. Spence, a risk is said to be material “when a reasonable person in what the physician knows or should know to be the patient’s position would be likely to attach significance to the risk or cluster of risks in determining whether or not to undergo the proposed therapy.”21 There-fore, informed consent is a bidirectional process that must evaluate and address the patient’s position and contextualize material risks to his/her life circumstances.

One particular challenge in obtaining informed consent for treatment from patients with neuro-oncological conditions relates to how the underlying disorder may alter a patient’s agency, and therefore capacity, to consent or refuse standard or experimental treatments. It has been previously shown that that the amount of information retained by patients during informed consent discussions is inversely related to the underlying disease severity.22 One study also demonstrated that patients frequently consented to treatment with only a modest appreciation of risk, with nearly one quarter of individuals reporting no risks despite being informed of them.23 Conversely, the presence of a cognitive deficit or the inability to perform a specific activity or task does not preclude rational decision making in all aspects of an individual’s life. Capacity is domain specific, meaning that it must be evaluated independently for specific decision-making processes. Although capacity, as a socio-legal construct, varies across time and jurisdictions, there is growing consensus that two fundamental elements of capacity are the ability to “understand” and to “appreciate” risks.24 The former describes an individual’s ability to comprehend and retain information, whereas the latter refers to the decision-making process whereby personal meanings are attached to the factual information.

• Informed consent is a bidirectional process that must consider the patient’s unique position and life circumstances.

• Capacity is domain specific and involves understanding and appreciating the nature of the illness and the risks of intervention.

Clinical Trials: Recruitment and Design

Health care professionals and societies have an ethical obligation to develop novel therapies to improve survival and quality of life of future patients with brain tumors and other neuro-oncological diagnoses. The recruitment of current patients into clinical trials is widely recognized as the gold standard for the legitimization of experimental treatments. Historical failures to ethically recruit patients into clinical research have informed present practices and emphasize the importance of the ethical conduct of experimental medicine. From the Nuremburg codes to the subsequent Declaration of Helsinki and from the lessons of the Tuskegee syphilis study to the publication of the Belmont Report, high ethical standards are now enshrined in the missions of institutional review boards (IRBs) (Table 46.2).25 Although seemingly simple, ethical challenges may arise during all stages of the recruitment of subjects for clinical research. The challenges that must be considered range from advertising the trials26 to remuneration or payment of subjects involved in studies that are associated with varying degrees of risk.27–29

Thorough pre-enrollment discussions with prospective research subjects are necessary prior to their participation in experimental studies. Patients’ assessment of experimental risk is complex and value-laden; therefore, risk perception may not be congruent with actual risk.30 Furthermore, consent to participate in research trials differs from that for nonexperimental therapies because the risks of the latter are inherently uncertain; therefore, choices made based on perceived risk may be misguided. The challenges of ethically recruiting patients with neuro-oncological diagnoses into clinical trials are further compounded by the fact that they are often highly motivated to pursue novel treatments given the dismal prognoses with which they are often faced. These patients, therefore, may fail to recognize that the goal of experimental therapy is to benefit future patients. As such, patients often underestimate the risk and overestimate the benefit of participation in clinical research.31,32

Table 46.2 Selected Seminal Guidelines on the Ethical Conduct of Research in Human Populations

| Work | Year Published | Purpose |

| Nuremberg Code | 1947 | 10-point statement meant to prevent future abuse of human subjects in response to inhumane experimentation on vulnerable populations during World War II |

| Declaration of Helsinki | Multiple revisions | Extensive work describing importance of ethical research practices, basic principles for its conduct, and the combination of research with clinical care |

| Vancouver Group (International Committee of Medical Editors) | Multiple revisions | Consensus guidelines regarding ethical issues in the reporting and publication of research findings, particularly pertaining to conflicts of interest, privacy and confidentiality |

| Belmont Report | 1978 |