Emerging Endoscopic Techniques in the Management of IBD-related Neoplasia

Nicole C. Panarelli

Ellen J. Scherl

Rhonda K. Yantiss

Endoscopic examination plays a critical role in diagnosis, management, and treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. One of its most important applications in this patient group is surveillance for development of dysplasia and carcinoma. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease have an increased lifetime risk of colorectal adenocarcinoma, which is usually preceded by onset of dysplasia. Factors most strongly associated with increased cancer risk in this patient population include prolonged (>10 years) disease duration, pancolitis, family history of colorectal cancer, and concurrent primary sclerosing cholangitis.1, 2 and 3 Unfortunately, early neoplastic changes in the colonic mucosa may be difficult to identify endoscopically, and thus, enhancing techniques that improve dysplasia detection are needed. This chapter discusses emerging endoscopic techniques and their potential roles in the management of inflammatory bowel disease.

CLASSIFICATION OF DYSPLASIA

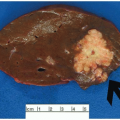

Inflammatory bowel disease-related neoplasia is broadly classified as elevated dysplasia and flat dysplasia. Elevated lesions, or dysplasia-associated lesions or masses (DALMs), are further subclassified based on their resemblance, or lack thereof, to colonic adenomas (Figure 15.1). Adenoma-like DALMs are circumscribed lesions, similar to sporadic colorectal adenomas. Nonadenoma-like DALMs appear as plaques, strictures, or ill-defined, broad-based nodules. Flat dysplasia is much less common, accounting for less than 5% of inflammatory bowel disease-related dysplasias. It is, by definition, endoscopically inapparent and discovered by random surveillance biopsies.4

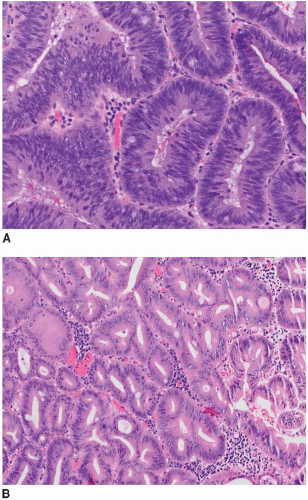

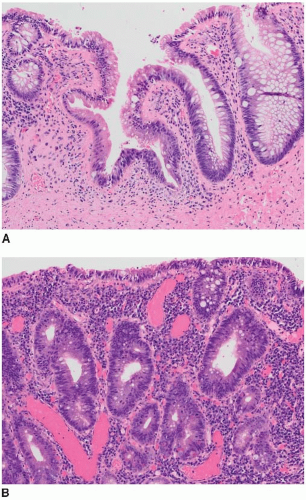

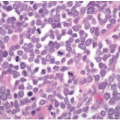

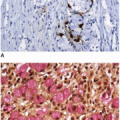

Both raised and flat dysplasias are histologically classified as low or high grade using criteria that parallel those applied to sporadic adenomas, as discussed in Chapter 4. Briefly, low-grade dysplasia shows crypts lined by epithelial cells with elongated, hyperchromatic, pseudostratified nuclei that do not mature at the luminal surface (Figure 15.2A). High-grade dysplasia contains cell with round, stratified nuclei that show severe atypia and contain prominent nucleoli. Most high-grade dysplasias also display architectural complexity with cribriform and interanastomosing glands (Figure 15.2B). Lesions that show some degree of cytologic atypia but do not meet criteria for low-grade dysplasia may be classified as indefinite for dysplasia. This situation is typically encountered when cytologic atypia is present in the crypts, but not the surface epithelium, or when cytologic changes resembling those of dysplasia occur in combination with active inflammation (Figure 15.3).

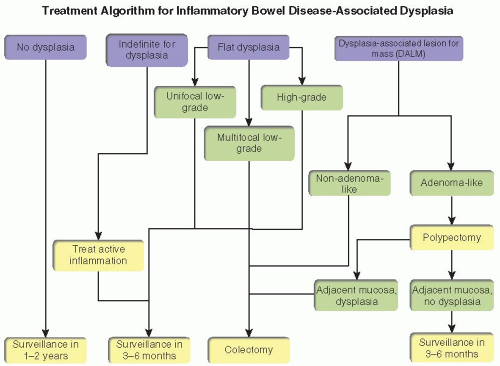

Accurate gross and histologic classification of inflammatory bowel disease-associated dysplasia is important because treatment recommendations vary depending on the endoscopic appearance of the lesion and severity of dysplasia (Figure 15.4). The natural history of low-grade dysplasia in inflammatory bowel disease is variable; 5% to 50% of cases are associated with cancer development.5,6 Unifocal low-grade dysplasia in nonadenoma-like DALMs or flat mucosa may be managed with either surveillance colonoscopy or proctocolectomy. Multifocal non adenoma-like DALMS and flat dysplasia are indications for colectomy owing to the high incidence of synchronous and metachronous adenocarcinoma in these situations.2 In contrast to flat dysplasia and nonadenoma-like DALMs, adenoma-like DALMs can be managed with complete endoscopic resection, similarly to sporadic adenomas, irrespective of dysplasia grade.7 Patients with adenoma-like DALMs are followed according to standard surveillance guidelines, provided that biopsies of the surrounding mucosa are negative for dysplasia and no dysplasia is found elsewhere in the colon.4

FIGURE 15.1: An adenoma-like DALM (white light) appears as a sessile polyp in the right colon. Biopsies of the surrounding nonpolypoid mucosa showed chronic colitis. |

CURRENT SURVEILLANCE GUIDELINES

Patients with ulcerative colitis undergo endoscopic surveillance at intervals that are determined based on the extent and duration of disease. Comprehensive colonoscopic examinations of the entire colon are performed at 1- to 2-year intervals. Examinations typically begin 8 to 10 years after onset of disease among patients with pancolitis or after 15 to 20 years among patients with disease limited to the distal colon. Suggested protocols call for random four-quadrant biopsies every 10 cm of colonic mucosa, producing at least 33 biopsies per procedure. Any mucosal irregularities are also sampled.3,8 This approach is both costly and time-consuming but has not been proven to reduce the risk of carcinoma development among patients with inflammatory bowel disease.9

ENDOSCOPIC TECHNIQUES USED IN EVALUATION OF DYSPLASIA

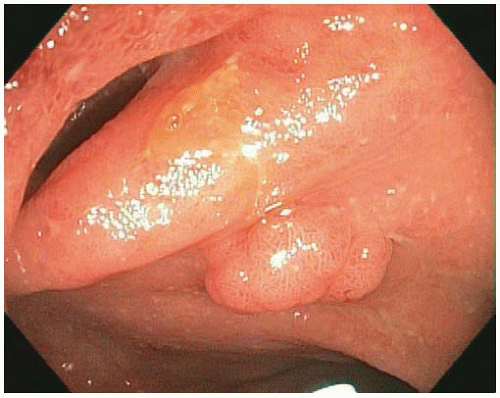

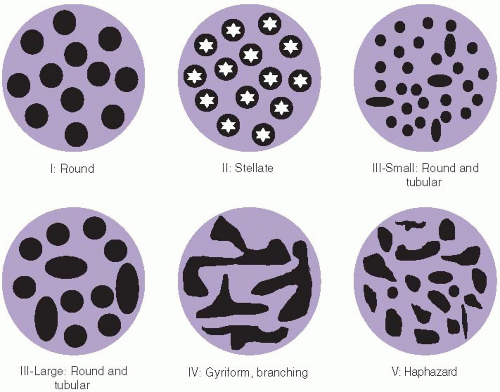

Surveillance of patients with inflammatory bowel disease is largely performed using white light (conventional) colonoscopy. Most colonoscopes contain magnifying lenses that enlarge white light images up to 150 times and reveal distinct patterns of surface colonic crypt openings that correlate with the presence of histologic dysplasia (Figure 15.5).10 Unfortunately, white light fails to detect a substantial number of colitis-associated dysplasias.2 Other endoscopic techniques have been recently developed with the hope to increase the sensitivity and specificity of endoscopic evaluation but decrease the number of biopsies required for dysplasia detection. These techniques are broadly grouped into chromoendoscopic methods and optical biopsy technologies, as discussed further below.

Chromoendoscopy

Chromoendoscopy employs dyes, selected wavelengths of light, or digitally reconstructed images to improve identification and characterization of mucosal abnormalities. Dye-based chromoendoscopy and narrowband imaging represent the most extensively studied and widely available advanced endoscopic techniques for inflammatory bowel disease surveillance.

FIGURE 15.5: Crypt patterns are used to classify lesions by chromoendoscopic findings based on the Kudo classification. Normal crypts are round, similar to each other, and evenly spaced in the mucosa (I). Stellate, regularly distributed crypts are observed in hyperplastic polyps and regenerative mucosa (II). Combinations of small round and tubular crypts (III-small) or large round and tubular crypts (III-large) are typical of dysplastic lesions, whereas branched (IV) or haphazardly arranged crypts (V) are worrisome for carcinoma.10 |

Dye-based Chromoendoscopy

Dye solutions, such as methylene blue and indigo carmine, enhance details of the mucosal surface. These solutions are painted or sprayed over the entire mucosal surface and preferentially absorbed by normal mucosa but spare areas of inflammation and neoplasia. The contrast unmasks subtle mucosal abnormalities and enables endoscopists to target their biopsies to dye-negative areas.11,12 Dye-based chromoendoscopy can be used in combination with magnifying colonoscopy to distinguish reactive surface pit patterns from those suspicious for dysplasia, as illustrated in Figure 15.5.

Dye-based chromoendoscopy improves dysplasia detection by three- to sixfold compared to white light colonoscopy and only increases the procedure time by approximately 10 minutes.11

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree