Diffuse Idiopathic Pulmonary Neuroendocrine Cell Hyperplasia

Keith M. Kerr

Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia (DIPNECH) is described in the WHO classification of lung tumors as a generalized proliferation of neuroendocrine cells (NECs), which may be associated with the development of carcinoid tumors, hence its inclusion in the classification as a preinvasive lung disease.1 There is no clear statement regarding how much NEC proliferation there must be for a diagnosis of DIPNECH to be made.

This is an extremely rare condition. In a review of DIPNECH written by the author in 2004,2 there were 17 cases published in the English literature including the original cases of Aguayo et al.3 who coined the term DIPNECH in 1992. Reviewing older literature back to the 1950s reveals descriptions of cases variously referred to as multiple bronchial adenomas or carcinoid tumors, which are probably examples of DIPNECH.4,5 and 6 A more recent study reported 19 cases of probable DIPNECH, collected from multiple institutions in the UK over a 15-year period.7 These authors quite reasonably suggested that while their experience was in part a collection of cases referred for consultation, DIPNECH may be an under-recognized condition that will be encountered more often as high-resolution computed tomography scanning is used more frequently.

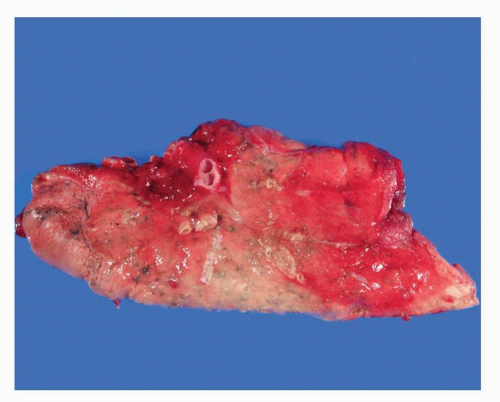

DIPNECH seems consistently to be found more frequently in females in the age range 30 to 70 years. All of the original cases of Aguayo et al.3 and many of the examples subsequently reported have been symptomatic. The typical presentation is of a slow increase in breathlessness with cough. Chest pain and hemoptysis are uncommon. Not infrequently, the patient is diagnosed with bronchial asthma. There is no association with smoking; most patients are never smokers. There may be no radiological abnormality but a frequent finding is a mosaic attenuation pattern (mosaicism) on the HRCT. Small millimeter-sized pulmonary nodules may also be found throughout both lung fields and in some cases larger tumors are seen (Fig. 28-1).8,9 and 10 It is apparent that cases of DIPNECH will also be encountered where pathology identical to that present in such symptomatic cases (see below) may be found incidentally in patients who have lung tissue resected for another reason, for example a solitary pulmonary nodule or a known primary lung cancer. There has been some doubt as to whether or not these asymptomatic cases should be diagnosed as DIPNECH, especially as such material does not allow the full pathological examination of the lungs for “generalized proliferation” of pulmonary NEC afforded by autopsy examination. The author is quite comfortable with the diagnosis of DIPNECH being given to asymptomatic cases but is still unsure regarding how much NEC hyperplasia is required for a diagnosis (see below).

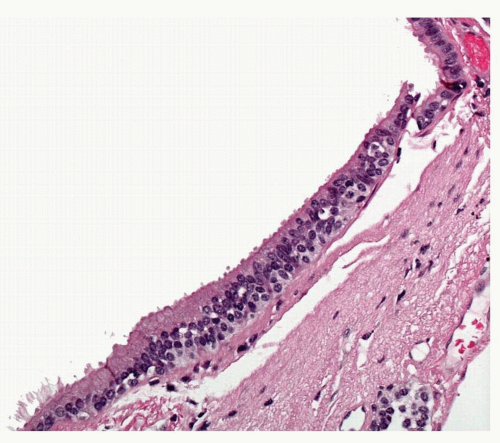

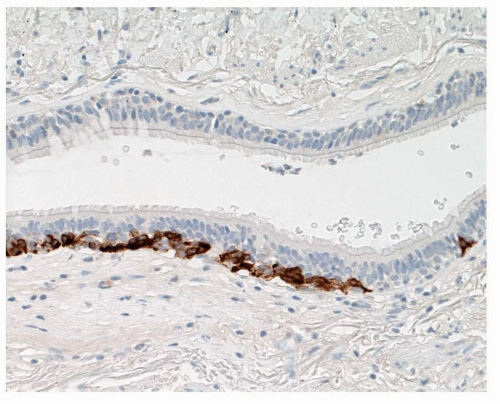

By definition, there is evidence of generalized diffuse hyperplasia of pulmonary NEC in this condition. Pulmonary NECs are normally present as singleton cells scattered within bronchial and bronchiolar epithelium. Very occasional small clusters of cells (neuroendocrine bodies) may be found in normal lungs. In DIPNECH, there is an increase in the number of singleton NEC;

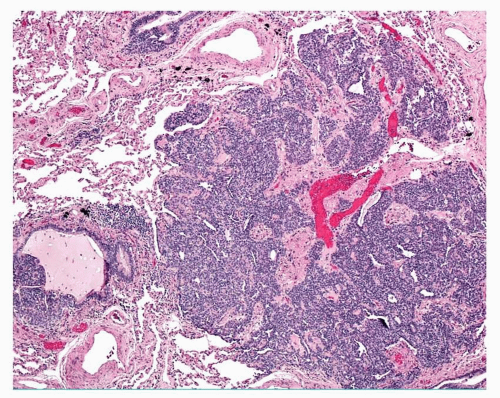

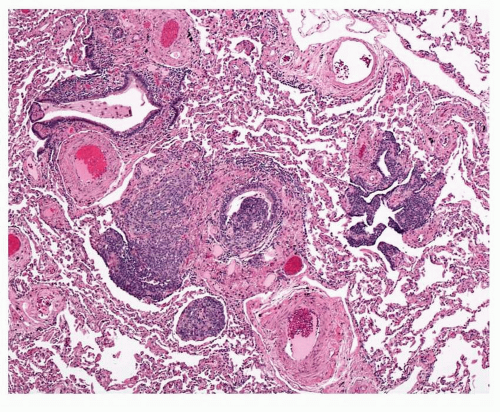

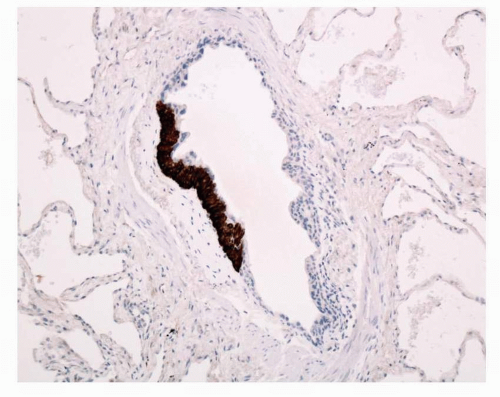

cells are found in rows of linear proliferation within the bronchial and especially bronchiolar epithelium and more nodules/neuroendocrine bodies are seen ( Figs. 28-2,28-3,28-4,28-5 and 28-6). These nodules may be large enough to protrude into the bronchiolar lumen and may cause airway obstruction ( Figs. 28-7,28-8,28-9,28-10 and 28-11). The proliferations of NEC may be associated with variable amounts of fibrosis (Figs. 28-12 and 28-13). Small airways remote from the NEC lesions may show fibrosis of the subepithelial connective tissue, sufficient to deserve classification as constrictive bronchiolitis (bronchiolitis obliterans), and these changes may be associated with a little chronic inflammation. This combination of changes seen in widespread distribution in pulmonary parenchyma would be a reasonable minimum requirement for a diagnosis of DIPNECH. The diagnosis of DIPNECH is normally made in the absence of significant background fibroinflammatory disease in the lung since the latter is associated with NEC hyperplasia (see below).

cells are found in rows of linear proliferation within the bronchial and especially bronchiolar epithelium and more nodules/neuroendocrine bodies are seen ( Figs. 28-2,28-3,28-4,28-5 and 28-6). These nodules may be large enough to protrude into the bronchiolar lumen and may cause airway obstruction ( Figs. 28-7,28-8,28-9,28-10 and 28-11). The proliferations of NEC may be associated with variable amounts of fibrosis (Figs. 28-12 and 28-13). Small airways remote from the NEC lesions may show fibrosis of the subepithelial connective tissue, sufficient to deserve classification as constrictive bronchiolitis (bronchiolitis obliterans), and these changes may be associated with a little chronic inflammation. This combination of changes seen in widespread distribution in pulmonary parenchyma would be a reasonable minimum requirement for a diagnosis of DIPNECH. The diagnosis of DIPNECH is normally made in the absence of significant background fibroinflammatory disease in the lung since the latter is associated with NEC hyperplasia (see below).

FIGURE 28-1 Gross image of wedge biopsy containing DIPNECH, showing focal small carcinoid tumorlets, predominantly within the central portion of the specimen. |

The obstruction of small airways is responsible for the asthma-like symptoms with which some patients with DIPNECH present seeking medical attention. The small airway pathology is also the cause of the signs of air trapping (mosaicism) on the HRCT scans. As a result of the small airways obstruction, there may be distal bronchiolectasis and mucous retention, as well as

accumulation of alveolar macrophages. Clinically, this condition is either stable or very slowly progressive. Oral steroids may be used with occasional success; at least one patient is reported, having been treated by lung transplantation.

accumulation of alveolar macrophages. Clinically, this condition is either stable or very slowly progressive. Oral steroids may be used with occasional success; at least one patient is reported, having been treated by lung transplantation.

FIGURE 28-3 Linear extensions of NEC in DIPNECH can be highlighted using neuroendocrine markers such as chromogranin. |

FIGURE 28-6 Chromogranin stain highlights the NEC nodule. Note the fine crescent of fibroblastic tissue between the bronchiolar muscle and the NEC nodule. |

FIGURE 28-7 Nodule of NEC hyperplasia in DIPNECH obstructing a bronchiole, which is dilated distal to the obstruction with retained secretion. |

FIGURE 28-9 Adjacent to the carcinoid tumorlet shown in Figure 28-8, a bronchiole is partly occluded by a NEC nodule. |

FIGURE 28-11 Adjacent to the DIPNECH tumorlet shown in Figure 28-10, a nodule is identified obstructing the constricted airway lumen.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|