Differential Diagnosis of Colorectal Carcinoma

Rhonda K. Yantiss

The recognition of colorectal carcinoma and its distinction from potential mimics poses several challenges, particularly in endoscopically obtained samples. For example, early invasive adenocarcinoma in colorectal adenomas may be difficult to distinguish from inflammatory changes in traumatized polyps. The colon is also a common site for primary and metastatic carcinomas that must be appropriately classified because therapeutic regimens for colorectal cancer differ from those for cancers originating in other organs. Management of primary colorectal carcinoma consists of complete surgical removal, if possible, with the addition of radiation and/or chemotherapy for local and systemic control, respectively. In contrast, metastases to the colorectum are managed with chemotherapy, and surgery and radiation are reserved for patients who require symptomatic relief of obstruction or bleeding. In this chapter we discuss the differential diagnosis of colorectal carcinoma as well as the ancillary immunohistochemical stains that aid in its identification.

DISTINCTION BETWEEN IN SITU AND INVASIVE LESIONS

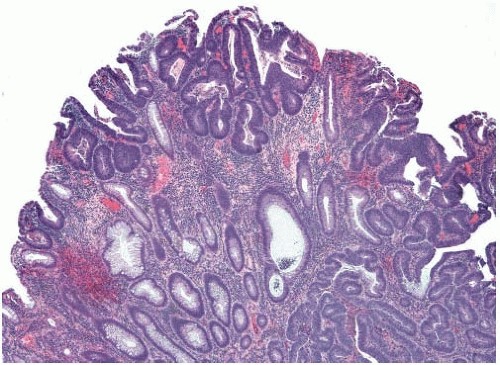

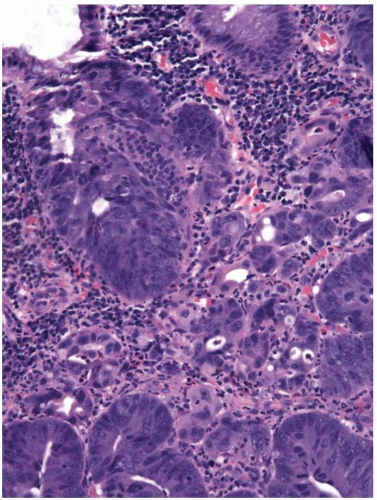

Colorectal adenomas that show high-grade dysplasia (intraepithelial carcinoma) and carcinomas limited by the muscularis mucosae (intramucosal carcinoma) are staged as carcinomas in situ (pTis) and adequately treated by polypectomy. The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies such lesions as intraepithelial and intramucosal neoplasia, respectively, in order to avoid terminology that may trigger overly aggressive management.1 However, invasive adenocarcinoma can mimic “in situ” neoplasia when it grows in the mucosa (Figure 10.1). It frequently colonizes the basement membrane, which induces maturation of malignant epithelium and simulates the appearance of an adenoma with highgrade dysplasia. Invasive adenocarcinoma also lacks a desmoplastic stromal response when it extends into the lamina propria, mimicking the appearance of intramucosal carcinoma (Figure 10.2). Several helpful features distinguish between primary neoplasia and colonization of the mucosa by invasive carcinoma. Most colorectal adenomas with high-grade dysplasia also show low-grade dysplasia, so a complete absence of the latter raises the possibility of mucosal colonization by a more deeply invasive tumor. Microvesicular or foamy cytoplasm is unusual in intestinal adenomas, but is characteristic of some secondary tumors that show a predilection to colonize the basement membrane, such as pancreatic carcinoma (Figure 10.3). Since most invasive carcinomas associated with adenomas are well-to-moderately differentiated, the presence of a high-grade tumor that infiltrates the lamina propria raises the possibility of metastasis.2 Given the propensity for invasive carcinomas to mimic in situ lesions in mucosal biopsies, diagnoses of high-grade dysplasia and intramucosal carcinoma should only be made when one is confident that the entire lesion has been removed (i.e., polypectomy specimens).

MIMICS OF INVASIVE ADENOCARCINOMA

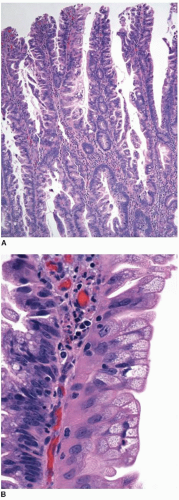

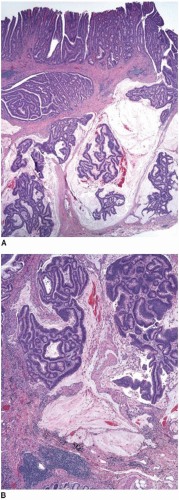

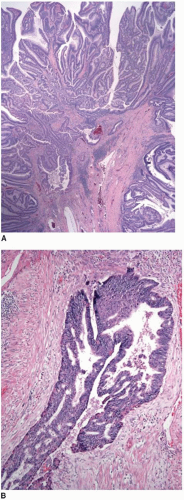

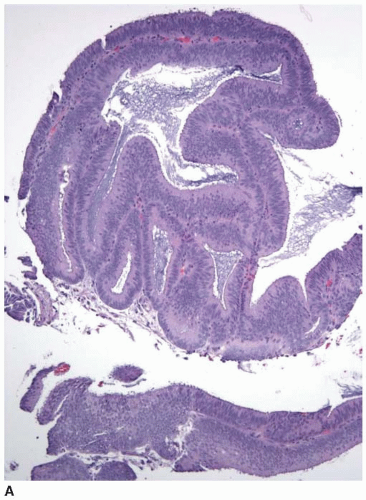

Most superficially invasive adenocarcinomas are identified in polypectomy specimens. Recognition of submucosal invasion is generally straightforward, although potential mimics do occur. Large pedunculated polyps, particularly those in the distal colon that are subjected to luminal or endoscopic trauma, can show epithelium in the submucosal stalk. This finding has been termed “epithelial misplacement” and “pseudoinvasion” in the literature, although “epithelial displacement” more accurately describes this phenomenon. Twisting of the polyp stalk presumably causes herniation of mucosal elements through the muscularis mucosae into the submucosa. The histologic distinction between displaced epithelium and invasive adenocarcinoma has significant clinical implications because some superficial adenocarcinomas require colectomy and staging of regional lymph nodes, whereas adenomas with epithelial misplacement are treated adequately by simple polypectomy, as discussed in Chapter 9. Several features help distinguish adenomas with displaced epithelium from invasive adenocarcinoma (Table 10.1).3,4 Displaced submucosal epithelium has a lobular configuration with a distinct rim of lamina propria and resembles the epithelium at the polyp surface (Figure 10.4A). Benign, displaced crypts in the submucosa dilate and rupture, inciting an inflammatory response to extruded mucin, and stromal hemorrhage and hemosiderin deposits are common (Figure 10.4B). Endoscopic manipulation of large adenomas also causes traumatic herniation of mucosa into the submucosa with mucin extrusion, scarring, and hemorrhage (Figure 10.5). Unlike displaced benign epithelium, invasive adenocarcinoma typically grows in an expansile, infiltrative fashion (Figure 10.6A). It is unassociated with lamina propria tissue and incites a desmoplastic stromal response. Malignant epithelial cells are cytologically atypical with high-grade nuclei, nuclear pleomorphism, and clumped chromatin (Figure 10.6B).

Morphologic assessment alone may be inadequate to distinguish displaced benign epithelium from invasive adenocarcinoma in some cases, such as those in which displaced epithelium shows high-grade dysplasia.3 Immunohistochemical expression of several biomarkers can facilitate detection of invasive adenocarcinoma. Invasive adenocarcinoma in adenomas shows increased nuclear staining for TP53 when compared with the surface adenomatous epithelium in nearly two-thirds of cases, whereas increased staining of benign misplaced epithelium is quite rare.5 Matrix metalloproteinases, which comprise a family of enzymes that play a vital role in angiogenesis and stromal breakdown and aid invasion of malignant epithelial cells into highly vascularized stroma, are overexpressed in the stroma and epithelium of most invasive adenocarcinomas.6 These include matrix metalloproteinase-1 and stromelysin-3, which are strongly expressed in most carcinomas in comparison with less than 50% of adenomas with displaced epithelium.7 Nearly two-thirds of invasive adenocarcinomas show diminished membranous staining for E-cadherin, and more than 90% show discontinuous, or absent, collagen IV staining of the basement membrane. These markers remain unaltered in adenomatous epithelium in any location.4,8, 9 and 10

Table 10.1 Features That Aid Distinction Between Misplaced Epithelium and Invasive Adenocarcinoma in Colorectal Polyps | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

DISTINGUISHING PRIMARY COLORECTAL CARCINOMA FROM OTHER ENTITIES

General Features

When metastases from another site involve the colonic mucosa, they may be difficult to distinguish from primary colonic cancers. Features suggestive of a primary malignancy include a concurrent adenomatous precursor lesion, regional lymph node involvement, and location of the tumor epicenter in the luminal aspect of the bowel wall. Multicentricity is more typical of a metastasis than primary colorectal cancer. However, none of these features is exclusively seen in either primary or secondary tumors. Metastatic tumors may colonize the mucosa and grow along the basement membrane, mimicking the appearance of an adenomatous component, as previously described (Figure 10.3). Mucosal colonization is a common feature of metastases of gastrointestinal origin and of endometrioid adenocarcinomas of müllerian origin (Figure 10.7). More than a third of metastases to the colon also involve regional pericolic lymph nodes, thereby simulating the disease distribution of a primary cancer.11

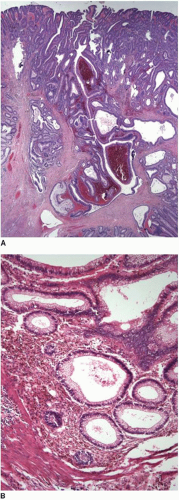

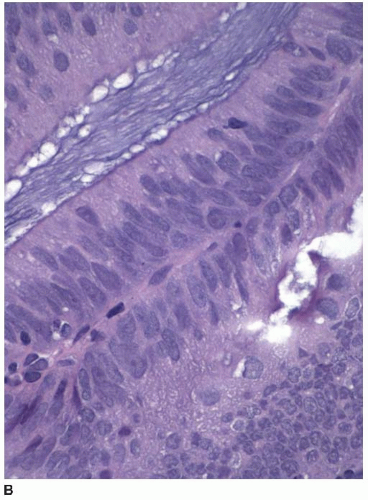

FIGURE 10.7: Endometrioid adenocarcinoma from a primary uterine tumor closely simulates a colonic neoplasm in mucosal biopsies (A). |

FIGURE 10.7: (Continued) Colonization of the colonic surface induces maturation in this gynecologic cancer such that the features closely simulate those of a colorectal neoplasm (B). |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree