Diagnosis of Immediate Hypersensitivity

Anju T. Peters

Jennifer S. Kim

Immediate hypersensitivity is defined as the presence of immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies in response to an allergen. It is one of the explanations for conjunctivitis, rhinitis, and asthma. In addition, it may be responsible for some cases of anaphylaxis, urticaria, angioedema, atopic dermatitis, and drug reactions. Many other causative explanations are possible for each of these conditions. Consequently, when a patient has been troubled enough with one of these conditions to consult a physician, it is necessary to perform a complete medical evaluation.

First, it must be determined if the symptoms are allergic in origin or if they have another cause. If the symptoms are considered to be allergic in origin, a more specific diagnostic evaluation must be completed to identify the allergen responsible for producing symptoms. In addition, various other factors must be evaluated. The degree of sensitivity to an allergen may vary among patients, as may the degree of exposure to a particular allergen. Many patients are sensitized to multiple allergens, and the cumulative effects of exposure to several antigens may produce severe or persistent symptoms. The influence of nonimmunologic phenomena also must be evaluated. Infections, inhaled irritants, fatigue, and emotional problems can be significant factors in varying degrees. Considering the large number of variables, it is not surprising that the most important portion of any clinical evaluation is the expertly taken history.

Patient History

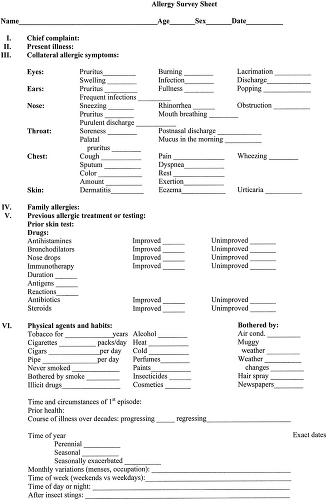

Many techniques have been used in obtaining a history, including the use of forms by the patient or the interviewer (Fig. 8.1). These may be convenient, but they can only facilitate and not replace the careful inquiries of a skilled historian. In some cases, the salient points can be obtained with relative ease, but generally a complete history is attainable only after considerable time and energy has been invested.

The history provides most of the information necessary for diagnosis. Diagnostic testing may be indicated to confirm or refute the suspected diagnosis. It is the clinician’s responsibility to select allergens appropriately and to be cognizant of potential adverse effects, particularly in patients suspected to be highly sensitized.

History to Establish Presence of Immediate Hypersensitivity

The history is taken in the same way as any medical history. The patient is asked to state the major complaint and to describe the symptoms. During the history, the presence or absence of symptoms of nonallergic conditions must be determined. Particular attention should be focused on which organs are affected. Characteristic details of the allergic history should be specifically noted.

Are there other symptoms in addition to the presenting complaint that may be allergic in origin? In patients complaining of upper or lower airway disease, the presence of sneezing, rhinorrhea, nasal congestion, anosmia, ear fullness, palatal pruritus, ocular

irritation, intermittent hearing loss, wheezing, dyspnea, or cough should be determined. Several allergic symptoms frequently exist simultaneously even if the patient does not associate them with a common cause. If several of these symptoms are present, it is more likely that they all have an allergic origin. Conversely, a symptom in a single organ system, such as isolated nasal obstruction, is less likely to be allergic.

Are symptoms bilateral? Unilateral symptoms, whether they are ocular, nasal, or pulmonary, suggest the presence of nonallergic conditions, often anatomic in nature.

Is there a family history of atopic disease? Most allergic patients have a positive family history (1,2). Specifically ask about allergic diseases in parents, grandparents, siblings, aunts, uncles, cousins, and children.

How has the patient responded to previous treatment? Information about response to previous therapy is useful. A good response to antihistamines increases the likelihood that the symptoms have an allergic origin. Response to a bronchodilator or anti-inflammatory therapy, either systemically or by inhalation, may give valuable information regarding the presence of reversible airway obstruction. A good response to previously administered immunotherapy would strongly implicate an allergic problem.

Are symptoms continuous or intermittent? Allergic symptoms are often intermittent. Moreover, intermittent exacerbations can occur for patients in whom symptoms appear to be continuous.

Are there specific triggers? A careful historian can often narrow the list of suspected allergens responsible for the symptoms of allergic diseases. This facilitates selection of further diagnostic tests and minimizes the number of tests performed. Specifically, a detailed survey of the patient’s home, work, or school environment may identify potential triggers. Moreover, a list of medications, both prescription and over-the-counter, should be elicited and their potential role as a causative factor considered. For example, oral contraceptives, certain antihypertensives, and phosphodieserase type 5 inhibitors can cause rhinitis (3). Most cardioselective beta blockers are safe in asthmatics, but β-adrenergic blockers rarely can be responsible for wheezing and dyspnea (4–6). Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors can produce a severe persistent cough or angioedema (7,8). Chronic use of topical decongestants in the nose or eyes may lead to chronic nasal congestion or ocular irritation respectively (9,10). Awareness of these reactions can prevent unnecessary and expensive allergic evaluations. History is especially important in selecting appropriate food extracts for testing because of the

low specificity of in vivo and in vitro specific IgE testing (11).

Did the time course suggest an allergic reaction? Most anaphylactic reactions occur within minutes to hours of exposure to the allergen. For example, IgE-mediated reactions to oral antigens (i.e., food, medication) typically occur within 2 hours of exposure to a particular agent.

The evaluation should address the severity of the illness. Symptom severity helps to determine the extent of the diagnostic evaluation and the intensity of therapy. Whether the symptoms are nasal, ocular, pulmonary, or dermatologic, it is necessary to judge the subjective degree of discomfort they cause. Health care providers must also take into account the patient’s perceptions and expectations. Perceived severity may relate closely to its effect on spouses or parents, for example. The assessment of severity also includes more objective measures, such as frequency: the number of days that symptoms occur, number of hours that they persist, number of days lost from or being unproductive at work or school, and the number of days hospitalized. Certainly, special consideration should be given to life-threatening events.

Characteristics of Allergens

See Table 8.1 for a review of the important aeroallergens. Some general characteristics of the antigens responsible for allergic illnesses must be appreciated before an adequate clinical history can be obtained or interpreted. Although foods may be contributing factors in cases of infantile eczema, acute urticaria/angioedema, or anaphylaxis, they are rarely responsible for triggering chronic respiratory symptoms. Patients with concomitant food allergy and asthma are more likely to exhibit acute respiratory symptoms on exposure to the offending food antigen. However, asthmatics without a clear history of an acute reaction after ingestion of a particular food are not likely to have food allergy. The allergens most important in asthma and rhinitis are airborne environmental allergens. Several different groups of these aeroallergens are of major clinical significance, including pollen, molds, house dust mites, cockroach, and animal dander.

Table 8.1 Symptoms Characteristically Produced by Common Aeroallergens | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Pollen

The grains of pollen from plants are among the most important antigens that cause clinical symptoms. Most plants produce pollen that is rich in protein and therefore potentially antigenic. Whether a specific pollen regularly causes symptoms depends on several factors. The pollens that routinely cause illness usually fulfill four criteria: (1) the pollen grains are produced in large quantities by a plant that is prevalent locally; (2) they depend primarily on the wind for dispersal; (3) they are 2 μm to 60 μm in diameter; and (4) they are antigenic.

Many plants produce pollen grains that are large, thick, and waxy. Under natural conditions, transfer of pollen between flowering plants is accomplished chiefly by insects. The pollen is not widely dispersed in the air and therefore rarely clinically significant. In contrast, pollen grains that are small, light, widely dispersed by the wind, and highly antigenic cause significant allergic symptoms. In the United States, many trees, grasses, and weeds produce large quantities of highly antigenic, windborne pollen. The seasonal occurrence of tree, grass, and weed pollens varies with the geographic location, as discussed in Chapter 7. Even though many factors may alter the total amount of pollen produced in any year, the season of pollination of a plant remains remarkably constant in any one area from year to year. This is because pollen release is determined by length of day, which is consistent from year to year. The treating physician must know which pollens abound in the patient’s primary geographical area and the seasons of pollination.

Fungi and Molds

Many thousands of different fungi exist. The role of molds in many conditions is speculative, but some species have been definitely implicated in exacerbating symptoms in mold allergic individuals (12,13). Because fungi can colonize almost every possible habitat and reproduce spores prolifically, the air is seldom free of spores. Consequently, they are important in some patients with perennial symptoms. However, seasonal or local influences can greatly alter the number of airborne spores.

Periods of warm weather with relatively high humidity allow optimal growth of molds. If this period is followed by hot, dry, windy weather, the spores often become airborne in large concentrations. “Thunderstorm asthma” has been associated with increases in mold spores. A frost may produce a large amount of dying vegetation, but the decreased temperature may reduce the growth rate of fungi. In contrast, spring and fall provide the relative warmth, humidity, and adequate substrate necessary for the growth of fungi.

High local concentrations of mold spores are encountered frequently. Deep shade may produce high humidity because of water condensing on cool surfaces. High humidity may occur in areas of water seepage such as basements, refrigerator drip trays, or garbage pails. Food storage areas, dairies, breweries, air conditioning systems, piles of fallen leaves or rotting wood, and barns or silos containing hay or other grains may provide nutrients as well as a high humidity, and therefore may have high concentrations of mold spores.

Indoor Allergens

The indoor environment contains multiple potential allergens, including fungi, dust mites, and pet dander; their role as indoor antigens has been definitely established (14–16). Dermatophagoides species are recognized as the major source of antigen in house dust (17). Carpeting, bedding, upholstered furniture, and draperies are the main sanctuaries of dust mites in a home. They are discussed in Chapter 10. In tropical climates, storage mites such as Lepidoglyphus destructor and Blomia tropicalis are important indoor allergens (18,19). Dust mite–sensitive patients may have perennial symptoms, although these may be somewhat improved outdoors with less humidity or during summer months. They may have a history of sneezing, lacrimation, rhinorrhea, or mild asthma whenever the house is cleaned or the beds are made. In many dust mite–sensitive patients, the history is not so obvious, and the presence of perennial symptoms is the only suggestive feature.

In the inner city, cockroaches are an important allergen. Exposure and IgE sensitivity to cockroach is associated with increased asthma morbidity especially in inner city children (20,21). Both mite and cockroach allergen are airborne in rooms with activity. In the absence of activity, airborne levels decline rapidly.

Proteins from sebaceous, salivary, or perianal glands, and urinary proteins of animals can act as potent allergens (22–24). When warm-blooded pets live inside a home, these products can reach high concentrations and completely permeate the furniture, bedding, rugs, and air. The small particle size and aerodynamic characteristics of pet allergens make them easily airborne especially with minimal disturbance of the environment (25). A short-haired pet does not eliminate this hazard since skin and fur are reservoirs and not the source of the allergens. Although cats and dogs are involved most frequently, many other animals such as hamsters, guinea pigs, rabbits, or mice are occasionally responsible (26–28). Certain occupational groups such as laboratory workers, veterinarians, ranchers, farmers, or pet shop owners may be exposed to an unusual variety of animal dander (29,30).

A patient with clinical sensitivity to a household pet may have a history similar to that of dust mite–sensitive patients with perennial symptoms. In addition, they may have symptomatic improvement when leaving home. Symptoms may persist outside the home because allergen is often carried on clothing, however, and patients may use this as inappropriate evidence that animals that they do not wish to eliminate from the environment are not a cause of their problem. Many patients may relate a history of wheal and erythema at a skin site that was in contact with the animal. If a physician does not inquire about the presence of a pet, the patient’s symptoms may be completely misinterpreted and improper therapy may be prescribed.

Other Allergens

IgE-mediated food reactions may be responsible for anaphylaxis or urticarial reactions. These are discussed

further in Chapter 14. Similarly, certain drugs or venom stings may be responsible for immediate hypersensitivity reactions and are discussed in Chapters 17 and 12, respectively.

further in Chapter 14. Similarly, certain drugs or venom stings may be responsible for immediate hypersensitivity reactions and are discussed in Chapters 17 and 12, respectively.

Nonimmunologic Factors

Certain nonimmunologic factors so frequently aggravate allergic conditions that they should always be evaluated. Primary irritants such as tobacco smoke, paint fumes, hair spray, perfumes, cleaning agents, or other strong odors or more generalized air pollution may precipitate flares of allergic respiratory conditions (31). In addition, infections, especially viral, weather changes, exercise, and stress can worsen airway allergic diseases (32).

Physical Examination

Every patient should have a complete physical examination. Particular attention must be directed to sites affected by common allergic diseases: eyes, nose, oropharynx, ears, chest, and skin.

Conjunctivitis

Physical findings of allergic conjunctivitis are hyperemia and edema of the conjunctiva. Occasionally, a pronounced chemosis occurs associated with clear, watery discharge. Periorbital edema may be present, and, rarely, a bluish discoloration or “allergic shiner” around the eyes may occur.

Rhinitis

The examination of the nose requires good exposure and adequate light. In a patient with allergic rhinitis, the inferior turbinates usually appear to be swollen and actually may meet the nasal septum. They may have a uniform bluish or pearly gray discoloration, but more frequently there may be adjacent areas where the membrane is red, giving a mottled appearance. Polyps may or may not be seen within the nose. The skin of the nose, and particularly of the upper lip, may show irritation and excoriation produced by the nasal discharge and continuous nose wiping. In patients with nasal allergic disease, the ears should be examined for evidence of acute or chronic otitis media, either serous or infectious in nature. Nasal secretions also may be observed draining into the posterior pharynx. “Cobblestoning” of retropharyngeal lymphoid tissue may be observed.

Asthma

Physical findings in asthmatic patients are highly variable, not only between patients but also in the same patient at different times. When the asthmatic patient is not having an acute exacerbation, there may be no demonstrable abnormalities on auscultation even when evidence of reversible airway obstruction can be demonstrated with pulmonary function studies. In many instances, asthma is persistent, and wheezes may be heard even while the patient is feeling subjectively well. In some cases, wheezes will not be heard during normal respiration but can be heard if the patient exhales forcefully.

During an acute attack of asthma, the patient is often tachycardic and tachypneic. The patient appears to be in respiratory distress and usually uses the accessory muscles of respiration. Mechanically, these muscles are more effective if the patient stands or sits and leans slightly forward. Intercostal, subcostal, and supraclavicular retraction, as well as flaring of the alae nasi, may be present with inspiratory effort. On auscultation, musical wheezes may be heard during both inspiration and expiration, and the expiratory phase of respiration may be prolonged. These auscultory findings tend to be present uniformly throughout the lungs in uncomplicated asthma exacerbation. Asymmetry of auscultory findings might be caused by concomitant disease such as pneumonia, or by a complication of the asthma itself, such as occlusion of a large bronchus with a mucous plug. In severely ill patients, extreme bronchial plugging and loss of effective mechanical ventilation may be associated with disappearance of the wheezing and decrease in audible breath sounds. In critically ill patients, once alveolar ventilation has decreased significantly, they may have distant breath sounds along with hypoxemia and cyanosis.

Atopic Dermatitis

The findings on physical examination of a patient with atopic dermatitis vary widely. Individual lesions feature initial erythema followed by a fine papular eruption. The papules may coalesce to form ill-defined plaques, or they may progress to papulovesicles that may rupture to produce oozing and crusting. These lesions uniformly are markedly pruritic. Chronic lesions are characterized by lichenification. The skin appears thickened, coarse, and xerotic. There may be moderate scaling and alteration in pigmentation.

The distribution of the lesions varies with the age of the patient. In an infant 4 to 6 months of age, the initial lesions commonly occur on the cheeks, scalp, ears, and the neck. Older children typically have lesions in flexural areas specifically the antecubital and popliteal fossae. Adults may have localized involvement such as on the hands or generalized disease. Secondary bacterial infection is frequently present. Further details are described in Chapter 15.

Anaphylaxis, Urticaria, or Angioedema

During an anaphylactic episode, vital signs need to be closely monitored. Tachycardia and tachypnea are often

present. Most anaphylaxis is accompanied by skin manifestations varying from flushing to urticaria and/or angioedema (33). Upper or lower airway involvement may be present with tongue/laryngeal edema or wheezing respectively. Severe laryngeal edema or bronchospasm may result in respiratory arrest; hypotension or cardiac arrest may occur with cardiovascular collapse.

present. Most anaphylaxis is accompanied by skin manifestations varying from flushing to urticaria and/or angioedema (33). Upper or lower airway involvement may be present with tongue/laryngeal edema or wheezing respectively. Severe laryngeal edema or bronchospasm may result in respiratory arrest; hypotension or cardiac arrest may occur with cardiovascular collapse.

Urticaria is suggested by erythematous lesions that blanch under pressure and resolve typically within hours without sequelae, such as bruising or discoloration. Angioedema involves subcutaneous swelling especially of the lips, eyelids, tongue, or genitals. IgE-mediated angioedema typically resolves in 24 to 48 hours without sequelae. Angioedema that is bradykinin-mediated may require 3 to 5 days to resolve.

Other Examinations

Abnormalities of red cells or of the sedimentation rate are not associated with atopic disease. If such abnormalities are present, other illnesses or complications should be suspected. The differential white blood cell count is usually normal, with the frequent exception of eosinophilia that may range from 3% to 12%, especially in patients who have both atopic dermatitis and asthma. Higher eosinophil counts are not ordinarily seen in atopic diseases. The evaluation of eosinophilia is reviewed in Chapter 33.

Extensive laboratory evaluation for urticaria and angioedema is generally not required and is not cost effective. Laboratory evaluation and further work up including skin biopsy is suggested by the history. See Chapter 13 for further details.

Chest radiographs may be necessary to rule out concomitant disease or complications of asthma. Chest radiographs in patients with asthma may reveal hyperinflation or bronchial cuffing; however, most often they are normal (34). The utility of chest radiographs prior to admission for acute asthma exacerbations is controversial but radiographs are often recommended since they have been reported to reveal clinically significant abnormalities in 15% to 34% of patients (35–37

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree