Incidentally discovered pancreatic cystic lesions are increasingly common, affecting up to 10% to 15% of patients undergoing cross-sectional imaging. Although some pancreatic cystic neoplasms harbor invasive malignancy or the potential to progress over time, a majority are benign and can be observed safely. Accurate diagnosis is key to appropriate management. Diagnosis requires a multidisciplinary and multimodal approach. This review discusses each type of pancreatic cystic neoplasm and the current data on diagnosis and treatment.

Key points

- •

Pancreatic cystic neoplasms are becoming increasingly prevalent due to increased awareness and increased utilization of high-resolution cross-sectional imaging.

- •

Different types of pancreatic cystic neoplasms vary in risk of current and future malignancy. Accurate diagnosis is, therefore, key to selecting optimal management, which involves either surgical resection or clinical and radiologic surveillance.

- •

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs) present as 1 of 2 variants, main duct (MD-IPMNs) or branch duct (BD-IPMNs), with differing malignant potential and, hence, management. MD-IPMNs have a higher risk of malignancy and should be referred for surgical resection. BD-IPMNs are more likely to be benign and, particularly in older patients without high-risk features, such as mural nodules, can be observed.

- •

Mucinous cystic neoplasms (MCNs) represent another type of mucinous tumor with malignant potential. MCNs most often present in middle-aged women, in the body or tail of the pancreas, and should be referred for surgical resection.

- •

Serous cystadenomas (SCAs) are nonmucinous, benign lesions that often occur in older women and can be observed unless symptomatic or growing.

- •

Cystic pancreatic endocrine neoplasms (CPENs) are rare, potentially malignant tumors, with characteristic arterially enhancing walls on CT. CPENs should be referred for surgical resection.

- •

Solid pseudopapillary neoplasms (SPNs) are rare, potentially malignant tumors almost exclusively seen in young women. SPNs should be referred for surgical resection.

Introduction

Cystic lesions of the pancreas pose a growing diagnostic and management challenge. Incidental pancreatic cysts are now detected in 2.6% to 13.5% of adults undergoing CT or MRI, with an even higher prevalence, up to 10% to 40%, in those above the age of 80. A vast majority of such cystic lesions do not contain invasive cancer, but many subtypes—IPMNs, MCNs, CPENs, and SPNs—carry a risk of current or future malignancy and, therefore, may require surgical resection. The morbidity and mortality of pancreatic resection, however, mandate careful risk/benefit analysis of surgery versus surveillance for each individual patient and lesion. The current challenge for oncologists, gastroenterologists, and surgeons is 2-fold. The malignant behavior of pancreatic cysts must be predicted more accurately and then this information used to better stratify patients into surgical versus nonoperative management.

To provide clinical context to this question, this article reviews the most common types of pancreatic cystic neoplasms, detailing each disease’s characteristic clinical and radiologic features and recommended management, followed by a generalized approach to diagnosis and treatment. International consensus guidelines are included where relevant. Attention is paid to controversial diagnostic and treatment questions requiring further investigation.

Introduction

Cystic lesions of the pancreas pose a growing diagnostic and management challenge. Incidental pancreatic cysts are now detected in 2.6% to 13.5% of adults undergoing CT or MRI, with an even higher prevalence, up to 10% to 40%, in those above the age of 80. A vast majority of such cystic lesions do not contain invasive cancer, but many subtypes—IPMNs, MCNs, CPENs, and SPNs—carry a risk of current or future malignancy and, therefore, may require surgical resection. The morbidity and mortality of pancreatic resection, however, mandate careful risk/benefit analysis of surgery versus surveillance for each individual patient and lesion. The current challenge for oncologists, gastroenterologists, and surgeons is 2-fold. The malignant behavior of pancreatic cysts must be predicted more accurately and then this information used to better stratify patients into surgical versus nonoperative management.

To provide clinical context to this question, this article reviews the most common types of pancreatic cystic neoplasms, detailing each disease’s characteristic clinical and radiologic features and recommended management, followed by a generalized approach to diagnosis and treatment. International consensus guidelines are included where relevant. Attention is paid to controversial diagnostic and treatment questions requiring further investigation.

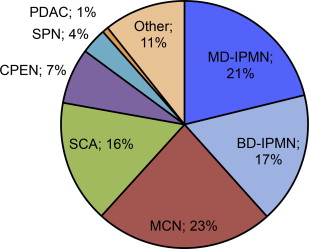

Disease entities

In light of increased use of high-resolution cross-sectional imaging and heightened awareness of pancreatic cystic neoplasms, pancreatic cysts are diagnosed with increasing frequency, at a smaller size (median diameter 1.6 cm vs 2.4 cm in the most recent vs prior decades), and, increasingly incidentally, now in more than two-thirds of cases. The most common types of resected pancreatic cystic neoplasms include IPMNs (27%–48%), MCNs (11%–23%), SCAs (13%–23%), CPENs (4%–7%), SPNs (2%–5%), and, infrequently, cystic degeneration of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas (PDACs) (1%–2%) ( Fig. 1 ). Over the past several decades, MCNs and SCAs have decreased in frequency, whereas IPMN has become the most common pathologic diagnosis. Current knowledge about each disease entity’s presentation, diagnosis, and management is discussed.

Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasm

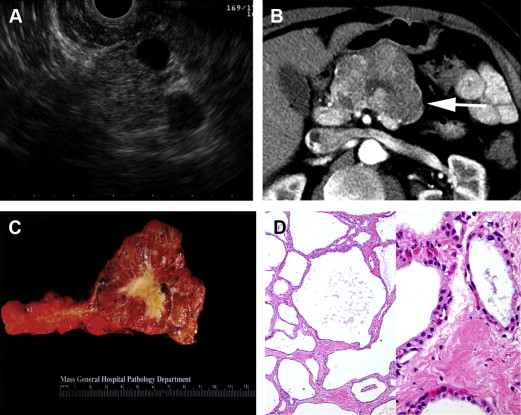

IPMNs have markedly increased in incidence over the past 20 years and are now the most commonly diagnosed and resected type of pancreatic cystic neoplasm. From a histologic standpoint, IPMNs are cystic, intraductal, mucin-producing tumors whose dysplastic cells range from benign adenoma to invasive carcinoma ( Fig. 2 ). IPMNs are suspected to represent a different disease entity than PDACs but are thought to progress through a similar pathway of benign to dysplastic to invasive disease. Two variants, MD-IPMNs and BD-IPMNs, are distinguished based on main pancreatic duct involvement, which, in the absence of histology, is defined as ductal dilatation on imaging. Mixed or combined IPMNs involving both the main pancreatic duct and side branches behave similarly to MD-IPMNs and are often grouped with MD-IPMNs for simplicity. Because MD-IPMNs carry a higher risk of malignancy at presentation and require immediate surgical resection, whereas the more commonly encountered BD-IPMNs are more likely benign lesions that can be managed nonoperatively, it is important to discern the variant of IPMN at the time of diagnosis to help guide management and determine prognosis.

Prevalence

BD-IPMNs are thought to represent the majority of small pancreatic cysts discovered incidentally on cross-sectional imaging. In several large surgical series, IPMNs are also the most commonly resected pancreatic cystic lesions, comprising 30% to 40% of all specimens, with slight predominance of MD-IPMNs over BD-IPMNs.

Demographics

IPMNs have an equal gender distribution and present at a median age of 65 to 67 years. Based on case series dating from the 1980s onward, a majority of patients with IPMN (60%–88%) present with symptoms, most often abdominal pain and, less frequently, weight loss, obstructive jaundice, or pancreatitis. Jaundice, in particular, occurs more frequently in patients with invasive versus noninvasive disease. More recently, however, IPMNs, in particular BD-IPMNs, are increasingly presenting as incidental radiologic findings.

Radiologic features

IPMNs are best characterized by 1 of 2 imaging modalities: (1) pancreas protocol CT, which uses multidetector acquisition of images with thin cuts through the pancreas and dual arterial and portal venous phases of intravenous contrast enhancement, or (2) MRI/magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), which combines routine contrast-enhanced MRI with special fast spin-echo sequences plus optional 3-D imaging of the pancreatic and biliary ducts. MRCP is more accurate than CT at detecting ductal communication, involvement of the main pancreatic duct, extent of disease throughout the pancreas, and high-risk cyst characteristics, such as mural nodules, and is, therefore, the imaging modality of choice for initial evaluation of a suspected IPMNs.

On either MRCP or CT, MD-IPMNs appear as a cystic and tortuous dilatation of the main pancreatic duct, with two-thirds of cases involving the head of the pancreas, 8% involving the entire duct, and a variable appearance of the associated pancreatic parenchyma, ranging from atrophic to enlarged and inflamed. BD-IPMNs, on the other hand, appear as solitary or multifocal cysts that communicate with the pancreatic ductal system but do not involve the main duct (ie, are associated with a normal-sized pancreatic duct; see Fig. 2 B).

Management

When clinical and imaging characteristics are insufficient to establish a diagnosis of MD-IPMNs or BD-IPMNs (eg, in the setting of a solitary cyst with normal-sized pancreatic duct), further evaluation with endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA) of cyst fluid can aid diagnosis and management decisions. Endoscopically, one-third of MD-IPMNs present with pathognomonic bulging of the papilla and mucus extrusion. EUS can additionally confirm the presence or absence of main duct involvement and better characterize solid components that raise the concern for malignancy (see Fig. 2 A). Cyst fluid analysis can also differentiate between mucinous and nonmucinous lesions, such as inflammatory pseudocysts or benign SCAs, but results are imperfect. Viscous, mucin-positive fluid is not always identified from mucinous lesions. Chemical fluid analysis demonstrating an elevated carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) level above an optimal cutoff of 192 to 200 ng/mL is only approximately 80% accurate in distinguishing mucinous versus nonmucinous cysts and can neither differentiate IPMN from MCN nor predict malignancy. Cyst fluid results, therefore, serve only as an adjunct to diagnostic evaluation and must be interpreted within the context of a patient’s overall clinical and radiologic presentation.

Regarding definitive management, MD-IPMNs more frequently harbor malignancy than BD-IPMNs, with approximately 43% of MD-IPMNs containing invasive carcinoma at the time of resection and an additional 19% harboring high-grade dysplasia (synonymous with carcinoma in situ). Current consensus guidelines from the 2010 meeting of the International Association of Pancreatology in Fukuoka, Japan (published in 2012, updated from the 2006 Sendai guidelines ), therefore, recommend surgical resection for all MD-IPMNs, as determined radiologically by either main pancreatic duct dilatation of 10 mm or greater on CT or MRI or borderline ductal dilatation of 5 to 9 mm with subsequent EUS confirmation of main duct involvement (ie, thickened walls or intraductal mucin or nodules).

BD-IPMNs, on the other hand, are much less likely to be malignant, with only up to 18% of cases containing invasive cancer and 8% containing high-grade dysplasia (reviewed by Tanaka and colleagues and Al-Haddad and colleagues ), frequencies that may be overestimated given the lack of specification between invasive carcinoma arising from an IPMN and concomitant PDAC arising in a separate site of the pancreas. Given the lower risk of malignancy with BD-IPMNs, and older age at presentation, current management has moved away from unconditional operation. The current 2012 Fukuoka guidelines recommend the following:

- •

Selective surgical resection of only high-risk BD-IPMNs, as determined by either of the following: (1) high-risk stigmata of malignancy (clinical: obstructive jaundice; CT/MRCP: enhancing solid component or main duct greater than or equal to 10 mm); or (2) worrisome features (clinical: pancreatitis; CT/MRCP: main duct 5–9 mm, nonenhancing mural nodule, thickened/enhancing cyst wall, abrupt change in duct caliber with distal atrophy, lymphadenopathy, or cyst size greater than or equal to 3 cm) plus EUS confirmation of either main duct involvement (as discussed previously), mural nodule (as opposed to a ball of mucin) (see Fig. 2 A), or cyst fluid cytology suspicious or positive for malignancy.

- •

Nonoperative surveillance for all other BD-IPMNs without high-risk or worrisome features. Frequency and type of surveillance is stratified by cyst size: (1) 2–3 cm: EUS in 3–6 months, then alternating EUS and MRCP (can lengthen interval if stable; consider surgery in young, fit patients who would otherwise require prolonged surveillance); (2) 1–2 cm: yearly MRCP or CT (can lengthen interval after 2 years of stability); or (3) less than 1 cm: 1-time follow-up MRCP or CT in 2 to 3 years.

Cyst size may be a weaker predictor of malignancy than other radiologic features, such as mural nodules, so it is allowable within the 2012 Fukuoka guidelines to observe BD-IPMNs larger than 3 cm, as long as no other high-risk or worrisome features are present and close surveillance with alternating EUS and MRCP is maintained every 3 to 6 months. In 1 series of 82 patients with BD-IPMN and no mural nodules (including 10 with cysts larger than 3 cm), all patients were managed nonoperatively, and only 5% developed new nodules over a median follow-up of 5 years, with only 1 of 4 cases containing high-grade dysplasia, and zero containing invasive carcinoma at the time of resection. A larger multicenter Japanese series of 349 BD-IPMN patients without mural nodules yielded similar results, with only 3% developing mural nodules or ductal dilatation and subsequent malignancy on surgical pathology.

A population that requires special consideration is patients with hereditary pancreatic cancer, defined by at least 2 other first-degree relatives with PDAC. These patients are at increased risk of PDAC and, if presenting with BD-IPMN, should be offered surgical resection at a lower threshold (ie, if they present with any worrisome features on MRCP or CT). If not immediately operated on, such patients should be managed with close endoscopic and radiologic surveillance.

Of historical note, the 2006 consensus Sendai guidelines had recommended surgery for all BD-IPMNs with either symptoms, main pancreatic ductal dilation greater than 6 mm, mural nodules, or cyst size greater than or equal to 3 cm. Subsequent studies found these guidelines to be nonspecific, with a positive predictive value of only 22% for malignancy (high-grade dysplasia or invasive carcinoma), thereby providing the impetus for the updated 2012 guidelines, discussed previously.

Outcomes

For both MD-IPMNs and BD-IPMNs, noninvasive disease is associated with excellent long-term survival, whereas invasive IPMN portends worse prognosis, albeit better than standard PDAC. After resection, 5-year disease-specific survival for noninvasive IPMN (including adenoma, borderline, and high-grade dysplasia) compared with invasive IPMN (carcinoma) is estimated to be 95% to 100% compared with 46% to 63%. Recurrence, either locally or with distant metastases, occurs more frequently in patients with invasive IPMN, with variable frequency and timing reported in the literature, in up to 41% to 44% of invasive cases, at a mean duration of 21 to 28 months after initial resection.

The histologic subtype of IPMN also has an impact on prognosis. A majority of MD-IPMNs demonstrate intestinal-type histology and frequently progress to colloid carcinoma, which is invasive but more indolent than standard PDACs. A minority of MD-IPMNs are of the oncocytic subtype, which can progress to an indolent form of oncocytic carcinoma, or the pancreaticobiliary subtype, which rarely can progress to tubular carcinoma, an aggressive histology that behaves similarly to PDACs. Alternatively, most BD-IPMNs are of the gastric subtype, which only infrequently progresses to the aggressive form of tubular carcinoma. Five-year overall survival was found 89%, 84%, 52%, and 94% for the intestinal, oncocytic, pancreaticobiliary, and gastric subtypes, respectively. Likewise, in a series of resected MD-IPMNs and BD-IPMNs, 5-year overall survival for patients with invasive disease was significantly better for those with colloid versus tubular carcinoma (83% vs 24%).

Current controversies and future directions

More accurate diagnosis and prediction of malignancy represent major challenges in current IPMN management as well as management of pancreatic cysts in general. Few studies report predictors of malignancy in MD-IPMNs, except to say that main duct involvement, itself, is associated with invasive disease in IPMNs. Based on multivariate analysis of a cohort of 219 patients with resected MD-IPMNs or BD-IPMNs, Correa-Gallego and colleagues developed a preoperative nomogram to better predict high-grade dysplasia or invasive carcinoma in IPMNs prior to surgical resection. Weight loss, history of prior malignancy, male gender, and solid component were significantly associated with malignant MD-IPMNs, whereas solid component, weight loss, and cyst size were significantly associated with malignant BD-IPMNs. The nomograms require prospective validation and are limited by lack of inclusion of EUS/FNA features.

The exact role of EUS/FNA in risk-stratifying IPMN lesions remains to be determined. EUS, in particular contrast-enhanced EUS, may be able to better characterize mural nodules and thus predict which lesions warrant resection. EUS-guided FNA of cyst fluid with subsequent cytologic analysis for high-grade atypical epithelial cells or obviously malignant cells is approximately 80% accurate at predicting malignant disease in IPMNs and MCNs. Cell yield from cyst fluid, however, can be low. Chemical analysis of cyst fluid, in particular CEA level, was suggested by some groups to predict malignancy but has not been reproducible. Molecular assessment of cyst fluid (eg, DNA analysis for oncogenic KRAS or GNAS mutations and/or amplifications), microRNA (miRNA) profiling, cytokine measurement (eg, of interleukin [IL]-1ß and prostaglandin E 2 [PGE 2 ]), and mucin proteomic profiling may each improve prediction of malignancy but require further investigation. Overall, EUS/FNA is promising but prone to interobserver variability and operator dependency, should be performed in centers with expertise in these techniques, and requires further validation prior to widespread use. Ultimately, predicting current and future malignancy within an IPMN lesion likely requires incorporation of clinical, imaging, and multiple EUS/FNA features.

An additional question pertains to the frequency of surveillance after resection of IPMNs. In the setting of invasive disease, the 2012 Fukuoka guidelines recommend similar surveillance as recommended for PDACs. Even with noninvasive IPMNs, however, there is an estimated 1% annual risk of developing concomitant PDAC, supporting the hypothesis of a field defect wherein the entire pancreas is predisposed to malignancy and leading some groups to maintain twice-yearly clinical and imaging surveillance even after resection of benign IPMNs.

Mucinous Cystic Neoplasm

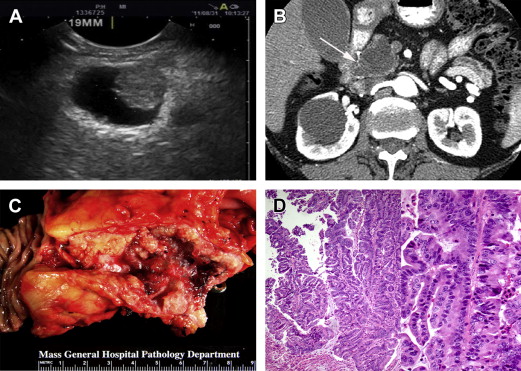

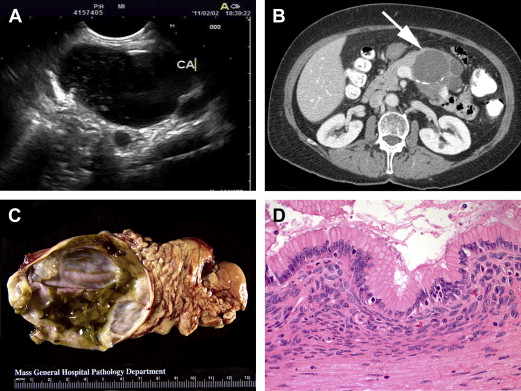

MCNs represent a different type of mucinous cystic tumor of the pancreas, more often premalignant than frankly malignant and distinguished from IPMNs based on the presence of a pathognomonic ovarian-like stroma surrounding the cyst’s inner epithelial layer as well as an absence of communication with the pancreatic duct ( Fig. 3 ). Despite a low risk of malignancy at presentation, MCNs harbor a risk of progressing to invasive carcinoma and, therefore, warrant surgical resection in young and healthy patients who would otherwise require years of radiologic surveillance. Presentation and management are discussed.

Prevalence

MCNs have decreased in prevalence but still comprise 25% of all resected pancreatic cystic neoplasms.

Demographics

MCNs almost exclusively present in middle-aged women at an average age of 40 to 50 years. In several large series, approximately 60% to 70% of patients presented with symptoms, most often abdominal pain, whereas the remainder were diagnosed incidentally on imaging.

Radiologic features

Initial diagnostic evaluation should include pancreas protocol CT or MRCP, as for IPMN evaluation. MCNs nearly always present as a solitary cyst in the body or tail of the pancreas (see Fig. 3 B). These lesions lack communication with the pancreatic duct and can have thickened walls or septae in more than half of cases. Mural nodules are predictive of malignancy, as is the case with IPMNs.

Management

A solitary cyst in the body or tail of the pancreas, in a middle-aged woman, without ductal communication strongly suggests a diagnosis of MCN and eliminates the need for further evaluation prior to treatment. If clinical and imaging features are indeterminate, however, EUS can be performed to better characterize the relationship of the lesion to the pancreatic duct (ie, to help distinguish MCNs from IPMNs [see Fig. 3 A]). EUS-guided FNA of cyst fluid also allows for molecular analysis (eg, cyst fluid CEA level, which, if greater than 192–200 ng/mL, favors a diagnosis of mucinous over serous lesions, and DNA sequencing, which, in the setting of a KRAS mutation without GNAS mutation, favors a diagnosis of MCN over other cystic neoplasms). Such tests require further validation prior to widespread use in diagnosis of MCNs and other pancreatic cystic lesions.

Regarding definitive management, the current 2012 Fukuoka consensus guidelines recommend surgical resection for all MCN. Rationale includes the 17% to 18% risk of malignancy (high-grade dysplasia or invasive cystadenocarcinoma), the risk of future progression even in benign disease, current inability to predict which lesions contain or will progress to malignancy, and the characteristic presentation of a distal lesion in an otherwise young and healthy patient, allowing for a less morbid operation (ie, distal pancreatectomy with possible splenic preservation as opposed to pancreaticoduodenectomy) in patients with relatively low perioperative risk. Alternative management, with nonoperative clinical and radiologic surveillance, would entail years of repeated cross-sectional imaging and, in the patient population described previously, would involve greater cost than benefit.

On surgical pathology, diagnosis of MCN is confirmed by the presence of ovarian-type stroma (see Fig. 3 D). If invasive cystadenocarcinoma is noted, postoperative surveillance, as for PDAC, is recommended but has not been shown to improve prognosis. If there is no invasion noted on pathology, the patient is considered cured, with zero risk of recurrence based on several large case series, and no special oncologic surveillance is required.

Outcomes

Prognosis is excellent after resection of noninvasive cystadenoma or in situ carcinoma but is variably poor for invasive cystadenocarcinoma. Five-year overall survival in 1 series was estimated to be 89% versus 17% for patients with noninvasive versus invasive disease, and 5 of the 6 invasive patients recurred and died within 5 years of surgery. More recent series describe slightly less dismal prognosis, with 5-year disease-specific survival rates of 95% to 100% and 57% to 83% for noninvasive and invasive MCNs, respectively, and an estimated recurrence rate of 40% at a mean duration of 33 months after surgery for those with invasive disease. Zero recurrences were detected after resection of noninvasive MCNs at an average follow-up of at least 5 years after surgery.

Current controversies and future directions

As for IPMNs, more accurate prediction of malignant behavior in MCNs will help identify which lesions require up-front resection and which, if any, can be observed. Cyst size greater than 4 cm or presence of mural nodules predicts malignancy with 100% sensitivity but lacks specificity and does not help identify those noninvasive lesions that will or will not progress to invasive carcinoma. Cyst fluid cytology from EUS/FNA, conversely, is specific but not sufficiently sensitive to predict invasive disease prior to surgical resection. Further molecular assessment of cyst fluid, as for IPMNs, may ultimately aid with risk stratification of MCN lesions.

A final question pertains to disease mechanisms and systemic therapy. Use of adjuvant chemotherapy after resection of invasive cystadenocarcinoma has not been rigorously studied and remains questionable in its impact on survival. Recent studies identifying activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway within the ovarian-like stroma of human MCNs and an analogous transgenic mouse model highlight novel potential therapeutic targets, but much remains to be elucidated about the molecular mechanisms of MCN progression.

Serous Cystadenoma

SCAs are nonmucinous, benign cystic neoplasms of the pancreas, which can be observed rather than resected and, therefore, stand apart from most other types of pancreatic cystic neoplasms. Cyst lining is composed of cuboidal epithelial cells rich in glycogen ( Fig. 4 D). The more common microcystic variant is composed of numerous small cysts grouped together in a honeycomb appearance (see Fig. 4 A–C), whereas the less common oligo- or macrocystic variant appears as a solitary cyst that is difficult to distinguish from pseudocysts, MCNs, or unifocal BD-IPMNs. Management requires careful diagnosis (detailed later).