Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is a prothrombotic disorder caused by antibodies to platelet factor 4/heparin (PF4/H) complexes. It presents with declining platelet counts 5 to 14 days after heparin administration and results in a predisposition to arterial and venous thrombosis. Establishing the diagnosis of HIT can be extremely challenging. It is essential to conduct a thorough clinical evaluation in addition to laboratory testing to confirm the presence of PF4/H antibodies. Multiple clinical algorithms have been developed to aid the clinician in predicting the likelihood of HIT. Once HIT is recognized, an alternative anticoagulant should be initiated to prevent further complications.

Key points

- •

Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) is a prothrombotic disorder caused by antibodies to platelet factor 4/heparin complexes. It classically presents with declining platelet counts 5 to 14 days after heparin administration and results in a predisposition to arterial and venous thrombosis.

- •

Establishing the diagnosis of HIT can be extremely challenging, especially in patients with multiple medical comorbidities.

- •

Once HIT is recognized, an alternative anticoagulant (direct thrombin inhibitor or fondaparinux) should be initiated to prevent further complications.

Definition and history

Unfractionated heparin (UFH) and its derivatives, the low-molecular weight heparins (LMWHs; henceforth, collectively referred to as heparin ), remain the most commonly prescribed anticoagulants for the prophylaxis and treatment of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in hospitalized patients. In a subset of treated patients (<5%), heparin elicits a life-threatening immune complication, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT). HIT is a self-limited hypercoagulable disorder occurring predominantly in hospitalized patients. The cardinal manifestations of HIT are declining platelet counts within 5 to 14 days after heparin exposure and a predilection for arterial and venous thrombosis.

In the 1950s, Weismann and Tobin first described the clinical syndrome of HIT. Subsequent studies revealed the immune origins of this syndrome with the identification of antibodies directed to antigenic complexes of platelet factor 4 (PF4) and heparin. With the advent of immunoassays for the detection of PF4/heparin (PF4/H) antibodies, it is now recognized that an asymptomatic immune response to PF4/H occurs far more commonly than clinical complications of the disease (thrombocytopenia and/or thrombosis). This article reviews our current understanding of the pathogenesis, clinical features, laboratory testing, and therapeutic options for patients with HIT.

Definition and history

Unfractionated heparin (UFH) and its derivatives, the low-molecular weight heparins (LMWHs; henceforth, collectively referred to as heparin ), remain the most commonly prescribed anticoagulants for the prophylaxis and treatment of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in hospitalized patients. In a subset of treated patients (<5%), heparin elicits a life-threatening immune complication, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT). HIT is a self-limited hypercoagulable disorder occurring predominantly in hospitalized patients. The cardinal manifestations of HIT are declining platelet counts within 5 to 14 days after heparin exposure and a predilection for arterial and venous thrombosis.

In the 1950s, Weismann and Tobin first described the clinical syndrome of HIT. Subsequent studies revealed the immune origins of this syndrome with the identification of antibodies directed to antigenic complexes of platelet factor 4 (PF4) and heparin. With the advent of immunoassays for the detection of PF4/heparin (PF4/H) antibodies, it is now recognized that an asymptomatic immune response to PF4/H occurs far more commonly than clinical complications of the disease (thrombocytopenia and/or thrombosis). This article reviews our current understanding of the pathogenesis, clinical features, laboratory testing, and therapeutic options for patients with HIT.

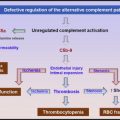

Cause and pathogenesis

PF4/H Complexes and the Immune Response in HIT

The primary physiologic role of PF4 is to neutralize the antithrombotic effect of heparin and heparin-like molecules (heparan sulfate, chondroitin sulfate) on cell surfaces. On platelet activation, PF4, a positively charged protein residing in platelet α-granules, is released in large amounts, binds to endothelial heparin sulfate, and displaces antithrombin from the cell surface. When patients are administered pharmacologic doses of heparin for thromboprophylaxis or for treatment, cell-bound PF4 dissociates from endothelial sites to form ultralarge complexes with circulating heparin. Recent murine studies have shown that these circulating and/or cell-bound PF4/H complexes are highly immunogenic in vivo. Once antibodies are formed, immune complexes containing immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody and antigen are capable of engaging cellular Fc receptors on platelets, monocytes, and neutrophils to promote cellular activation and thrombin generation.

Epidemiology of HIT

In recent prospective investigations using UFH and/or LMWH, the overall incidence of HIT is estimated at 0.5% to 0.8% of the treated patients. Drug and host characteristics contribute to the risk of developing HIT. Of the various drug-dependent characteristics influencing immunogenicity, chain-length (UFH > LMWH ≥ fondaparinux), animal source of heparin (bovine > porcine), and route (intravenous > subcutaneous), heparin chain length seems to be the most clinically significant. The incidence of HIT is approximately tenfold higher with UFH (∼3%) as compared with LMWH (0.2%) in patients receiving thromboprophylactic doses. These differences in UFH and LMWH subside, however, when treatment doses are administered. In a meta-analysis involving 13 studies and more than 5000 patients, the rates of HIT were comparable in patients receiving UFH or LMWH (LMWH 1.2% vs UFH 1.5%). Despite the increased utilization of LMWHs in recent years for the prevention of hospital-acquired VTE, there has been, surprisingly, no increase in the HIT incidence. Although rates of seroconversion are similar for fondaparinux and LMWH, the occurrence of HIT seems to be infrequent with fondaparinux.

Host risk factors include clinical context of heparin exposure and patient characteristics (age, gender, and race). Patients on the general medical, cardiology, and surgical services (orthopedic and trauma) are at higher risk than patients on obstetric, pediatric, or renal (chronic hemodialysis) services. The reasons for this variable risk are presently unknown but are thought to arise from differences in basal levels of platelet activation and circulating PF4 levels. Consistent with observations of a low incidence of HIT in pediatric and obstetric patients, a recent large analysis of hospital discharges of approximately 270 000 inpatient records showed that HIT was exceedingly rare in patients less than 40 years of age. In this same study, among patients with VTE, the incidence of secondary thrombocytopenia, presumably caused by HIT, was higher among blacks (relative risk [RR] 1.3) as compared with whites. Although one recent study showed a higher incidence of HIT among women (odds ratio of 2.4 ), other studies have found a slightly higher risk among men (RR 1.1). Several genetic polymorphisms, including homozygosity of the FcγRIIIa-158V allele, the protein tyrosine phosphatase CD148, and the interleukin-10 promoter, have been described in single-center studies of patients with and without HIT. The clinical significance of these findings remains to be established in larger studies.

Clinical elements of diagnosis

Because of the high incidence of asymptomatic PF4/H conversion (see the “Laboratory Elements of Diagnosis” section) in patients exposed to heparin, it is essential to understand the clinical features associated with disease presentation. Three diagnostic elements should comprise the clinical evaluation of patients suspected of HIT: (1) documenting the presence of thrombocytopenia and/or thrombosis, (2) establishing the temporal course of thrombocytopenia relative to heparin exposure, and (3) excluding other causes of thrombocytopenia. A detailed discussion of these clinical diagnostic elements and commonly used diagnostic algorithms is provided subsequently in the section Clinical Algorithms in Assessing Likelihood of HIT . Table 1 summarizes the clinical features commonly or infrequently seen in HIT.

| Consider HIT | HIT Unlikely |

|---|---|

Following clinical symptoms within 4–14 d of new heparin therapy or within 24 h of heparin reexposure a

|

|

Documenting the Presence of Thrombocytopenia and/or Thrombosis

Thrombocytopenia in HIT

Thrombocytopenia is an essential diagnostic feature of HIT and is reported to occur in approximately 95% of patients with HIT during the course of illness. Patients who develop skin necrosis are a notable exception to this diagnostic rule because thrombocytopenia frequently does not accompany this atypical manifestation. Thrombocytopenia in HIT can present as an absolute drop in platelet count less than the normal range (platelet count <150 × 10 9 /L) or as a relative decrease of 30% to 50% from the baseline counts. Absolute thrombocytopenia results in a moderate thrombocytopenia, with mean platelet counts of 50 to 70 × 10 9 /L. In the postoperative period, when platelet counts typically rebound to a higher number than the preoperative count, the immediate postoperative platelet count should be considered as the baseline platelet count for determining the change in platelet count. This revised definition of thrombocytopenia has been shown to be sensitive and specific for diagnosing HIT.

Less than 5% of patients with HIT will have a platelet count less than 20 × 10 9 /L. The presence of petechiae or extensive ecchymoses in the absence of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) should prompt a search for an alternative diagnoses (see Table 1 ). Severe thrombocytopenia as a manifestation of HIT is associated with a high risk of thrombotic complications, likely because of platelet consumption. In a retrospective series of 408 patients, patients with severe thrombocytopenia (defined as >90% decline from baseline counts) were noted to have an 8-fold higher risk for thrombotic complications as compared with patients with a less than 30% platelet count decline.

Several retrospective and prospective studies have shown that isolated thrombocytopenia is a harbinger of subsequent thromboses in patients (20%–50%). In one-third of patients, the thromboembolic complication (TEC) can occur concurrently or precede the development of thrombocytopenia. Because of the therapeutic implications of finding a VTE in patients with HIT with isolated thrombocytopenia, patients diagnosed with isolated HIT should undergo routine screening for subclinical TEC, such as lower extremity ultrasound.

Thrombosis in HIT

Thrombosis is the most feared complication of HIT. In prospective and retrospective series, thrombotic complications have been reported to occur in 29% to 57% of patients with HIT. In one registry, 25% of patients developed 3 or more thromboembolic complications. Before the availability of current therapies, 16% of all thrombotic complications were fatal and 9% of all thrombotic events resulted in limb amputation. In relation to thrombocytopenia, a large retrospective study of patients with HIT found that in 34% of patients, thrombotic complications will precede or occur concurrently with a major decrease in platelets.

Thrombotic events involving the venous circulation occur far more commonly than arterial thrombotic events, with reported frequencies of 2.4:1.0 to 4:1. Lower limb deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism compose most of the venous thrombotic events. Upper limb DVTs are also common but are reported to occur almost exclusively at central venous catheter sites. The postoperative period has also been strongly associated with venous thrombosis in HIT.

Arterial thromboses occur in 7% to 14% of patients affected with HIT. In one series of patients with HIT, a history of cardiovascular events, including myocardial infarction, and a history of cardiovascular surgery were associated with a significantly increased incidence of arterial thrombosis. In order of decreasing frequency, common sites of arterial thrombosis include limb artery thrombosis, thrombotic stroke, and myocardial infarction. Atypical sites of presentation including bilateral adrenal hemorrhage, venous limb gangrene, cerebral venous thrombosis, spinal ischemia, and skin necrosis should warrant consideration of HIT in the differential diagnosis.

Presently, there are no definitive means for predicting the risk of thrombosis in patients who develop isolated thrombocytopenia in HIT. Studies have shown that established risk factors for hypercoagulability, such as protein C, protein S, antithrombin clotting factor mutations, and/or platelet polymorphisms, do not contribute significantly to thrombotic tendency. Certain common serologic features occur at a higher frequency among patients with thrombotic HIT as compared with those with isolated thrombocytopenia in HIT, including IgG isotype, antibodies capable of platelet activation, and high antibody levels (as gauged by optical density [OD] and/or titer). Risk factors for thrombosis development are outlined in Table 2 .

| Predictors of Thrombosis in HIT | |

|---|---|

| Correlated with Thrombotic Risk | No Correlation with Thrombotic Risk |

|

|

Despite the risk associated with certain serologic features, the presence of platelet-activating IgG antibodies in some patients with asymptomatic PF4/H antibodies or the occurrence of low titer antibodies in other patients with a clinically confirmed diagnosis of thrombotic HIT does not permit unambiguous segregation of patients with and without HIT. Discontinuing heparin therapy after early recognition of HIT does not seem to lower the risk of subsequent thrombosis.

Establishing the Temporal Course of Thrombocytopenia Relative to Heparin Exposure

In heparin-naïve patients, platelet counts classically decline within 5 to 10 days of heparin initiation. As shown in a recent study of the evolution of the HIT immune response, 12 patients with HIT were examined serially for PF4/H antibody levels and platelet counts. As shown in Fig. 1 , seroconversions occurred at a median of 4 days from the start of heparin therapy, with a decrease in platelet count occurring 2 days after seroconversion (∼6 days from the start of heparin therapy). The interval time to when the platelet count decline met diagnostic criteria for HIT in this study (>50% platelet count decrease) occurred 4 days after seroconversion (median time interval of 8 days from the start of heparin). Thrombosis also occurred after seroconversion but was often coincident with changes in platelet counts. These observations, coupled with studies of murine models, suggest that patients’ PF4/H seroconversions must precede thrombocytopenia and/or thrombosis, and clinical events predating seroconversion are unlikely to be related to HIT. In 30% of patients with HIT, an atypical, rapid decrease in the platelet count, occurring at a median of 10 hours after beginning heparin therapy, can occur from preexisting, circulating PF4/H antibodies caused by recent heparin exposure (within 3–6 months). Another clinical variant of HIT presentation is delayed-onset HIT, in which platelet counts fall 10 to 14 days after last heparin exposure. Delayed-onset HIT is frequently associated with complications of DIC and/or extensive thrombosis and should be considered in patients presenting with new-onset thrombocytopenia within 2 to 4 weeks of a recent hospitalization.

Discontinuation of heparin should allow prompt resolution of thrombocytopenia. In clinical practice, platelet counts typically increase within 48 hours of heparin discontinuation, and thrombocytopenia usually resolves within 4 to 14 days. A prolonged duration of thrombocytopenia (>7 days) after heparin discontinuation has been linked with disease severity. Despite platelet count recovery, thrombotic risk remains high for 4 to 6 weeks because of the presence of circulating PF4/H antibodies ; these antibodies likely contribute to the development of delayed-onset HIT. The median time to antibody clearance is 85 to 90 days, although in one series, approximately 35% of patients were noted to be seropositive for up to 1 year. To what extent PF4/H seropositivity, in the absence of thrombocytopenia and/or thrombosis, predisposes patients to thrombotic complications remains controversial. Unlike other drug-induced thrombocytopenias, the risk of recurrent HIT with subsequent heparin reexposure seems to be low; but these findings have not been prospectively investigated. Although several retrospective analyses and case reports suggest that the risk of recurrence may be low in patients who become seronegative for PF4/H antibodies, current guidelines recommend avoiding routine heparin reexposure in these patients.

Excluding Other Causes of Thrombocytopenia

Most patients suspected of HIT are not likely to have disease. With the routine implementation of heparin thromboprophylaxis in most hospitals as well as the frequent occurrence of thrombocytopenia in hospitalized patients, the statistical likelihood that these two clinical scenarios will converge is far more likely than the occurrence of HIT. Illustrating this point was a recent study by Oliveira and colleagues of 2420 patients treated with heparin who were assessed for the development of thrombocytopenia (defined as a platelet count less than 150 × 10 9 /L, reduction in platelet count of 50% or more from the admission level, or both). In this study, 881 patients or 36.4% (95% confidence interval, 34.5%–38.3%) met the definition for thrombocytopenia while receiving heparin therapy; 13% of patients met both criteria of a decreased absolute platelet count as well as a reduction in platelet count of more than 50%. In this study, approximately 0.7% of patients were diagnosed with HIT.

The differential diagnosis of acute thrombocytopenia in hospitalized patients is extensive as shown in Table 1 (“HIT Unlikely” column). Thrombocytopenia is common in the intensive care units (ICU), occurring in 38% to 46% of patients. Thrombocytopenia is particularly problematic in the cardiac surgery setting, where patients have several risk factors for HIT, including recent heparin exposure, the inflammatory milieu of surgery, and high rates of PF4/H seroconversion. In one recent study of cardiac surgery patients requiring more than 7 days in the cardiac ICU, 21% of patients (70 out of 329) developed thrombocytopenia, with 67 out of 70 patients (95%) having alternative or non–HIT-related causes for thrombocytopenia. Adding to the complexity of the evaluation of cardiac surgery patients is the relatively frequent use of mechanical devices, such as intra-aortic balloon pumps (IABP). Thrombocytopenia is frequently encountered in patients with IABP, occurring at a frequency of 30% to 50% of cases.

Clinical algorithms in assessing likelihood of HIT

Given the broad differential diagnosis and frequency of thrombocytopenia in hospitalized patients, clinical algorithms have been developed to assist clinicians in tabulating the risk of HIT in a given patient.

4Ts Scoring System

The most widely used clinical scoring system is the 4Ts developed by Dr Warkentin at McMaster University. The 4Ts scoring system assesses the clinical diagnostic elements discussed earlier and assigns a score (0, 1, or 2; maximum total score of 8) for the following features: the magnitude of thrombocytopenia, timing of platelet count decrease or complication in relation to heparin use, thrombosis or other HIT-associated sequelae, and the absence of another explanation for thrombocytopenia. A 4T score of 6 to 8 is consistent with a high pretest probability of HIT, a score of 4 to 5 is consistent with an intermediate probability of HIT, and a score of 0 to 3 is consistent with a low probability of HIT. The diagnostic utility of the 4T score has been examined in numerous prospective and retrospective studies. In all studies to date, the 4Ts has consistently demonstrated excellent negative predictive value (NPV), with a 4T score less than 3 reliably translating into a low likelihood of serologically confirmed HIT. On the other hand, the positive predictive value (PPV) of the 4T scoring system is variable and highly dependent on the practitioner’s background. To demonstrate the effect of a practitioner’s experience in using the 4Ts scoring system, Lo and colleagues tested this algorithm at 2 medical centers (Hamilton, Canada and Greifswald, Germany [GW]). The practitioner applying the 4Ts at the Hamilton General Hospital (HGH) was Dr Warkentin, the developer of the 4Ts scoring system. In GW, the general practitioners used the 4Ts for diagnosing HIT. When the clinical scores were correlated with laboratory testing, the NPV was high at both medical centers (98% at HGH and 100% at GW). However, the predictive value of intermediate scores (HGH: 8 out of 28 [28.6%], GW: 11 out of 139 [7.9%]) and high scores (HGH: 8 out of 8 [100%], GW: 9 out of 42 [21.4%]) markedly differed by institution. The clinical utility of the 4Ts in predicting the likelihood of HIT was low in Germany, where primary care providers were using the algorithm, but much higher in Canada in the hands of an experienced HIT diagnostician. This study, as well as others, confirms that the PPV of intermediate and high scores is far less reliable than the NPV.

HIT Expert Probability Score

In an effort to improve on the specificity and the PPV of the 4Ts, the HIT Expert Probability (HEP) score was developed using expert opinion to refine the clinical scoring system. In this model, 26 experts were asked to assign points to 8 clinical features of HIT based on diagnostic relevance (magnitude of the decrease in platelet count, timing of the decrease in platelet count, nadir platelet count, thrombosis, skin necrosis, acute systemic reaction, bleeding, and other causes of thrombocytopenia). Based on the median score, each clinical feature was then assigned a point ranging from −3 to +3 and the HEP score, a pretest probability model, was created. In a validation study at a single institution, the HEP score demonstrated improved interobserver agreement and improved correlation with serologic HIT testing when compared with the 4Ts score. In this study, the HEP score was 100% sensitive and 60% specific for diagnosing HIT. However, unlike the 4Ts, which is fairly simple to perform, the HEP score is more complex to use. Additional prospective studies are needed to validate the HEP scoring system.

Cardiac Surgery (Lillo-Le Louet) Scoring System

Nowhere is the challenge of distinguishing HIT from other causes of thrombocytopenia more difficult than in the clinical setting of cardiac surgery. Cardiac surgery is associated with several comorbidities that confound the diagnosis of HIT, including several risk factors for thrombocytopenia (dilutional effect, infection/DIC, cardiogenic shock, mechanical devices, multiple medications), increased rates of thrombosis (20% in one recent retrospective study of non-HIT patients), and a high prevalence of PF4/H seroconversion (see “Laboratory Elements of Diagnosis”). Despite the high-risk features of this clinical setting, retrospective and prospective series have demonstrated that the postoperative risk of HIT after cardiac surgery is low (0.6%–2.0%). Because of the difficulty in recognizing HIT after cardiac surgery, Lillo-Le Louet and colleagues identified 3 independent clinical variables (platelet count pattern, time from cardiopulmonary bypass [CPB] to suspicion of HIT, and CPB duration) based on a clinical cohort suspected of HIT. In patients with HIT, a characteristic biphasic pattern of platelet count recovery was observed. Platelet counts initially decline for 2 to 4 days after surgery, then rebound into the normal range or beyond, and then decrease once again because of antibody development and HIT. Based on these observations, scores were assigned for platelet count, time course, or pattern (biphasic = 2, persistent thrombocytopenia = 1); time from CPB to date of HIT suspicion (≥5 days = 2, <5 days = 0); and CPB duration (≤118 minutes = 1, >118 minutes = 0). In their retrospective study, a score of 2 or more was associated with a high probability of HIT (PPV of 62%), whereas a score 5 or more was associated with a markedly higher PPV of 95%. In a recent prospective study of 1722 patients undergoing cardiac surgery, the Lillo-Le Louet scoring system was compared with that of the 4Ts in predicting the likelihood of HIT. In this study, both scoring systems were found to have a low PPV (56% for the 4Ts and 41% for Lillo-Le Louet) and low concordance (kappa coefficient = 0.39). The Lillo-Le Louet scoring system also had a lower NPV (78%) than the 4Ts (91%). The investigators concluded that the diagnostic performance of both scoring systems were low. However, the investigators found that the biphasic pattern of platelet count recovery in the post–cardiac surgery setting remained a strong predictor for HIT.

Laboratory elements of diagnosis

In clinical practice, most of the patients suspected of HIT are likely to have an intermediate clinical probability for HIT. In these patients, establishing the presence or absence of PF4/H antibodies by laboratory methods comprises an essential element of the diagnostic evaluation. This section discusses the types of immunologic and functional assays for diagnosing HIT.

Immunoassays

Immunoassays for the detection of PF4/H antibodies are widely available. These assays detect binding of antibodies from plasma or serum to immobilized PF4/H complexes. Bound antibody is then detected by secondary labeled antibodies using a colorimetric endpoint. Detailed descriptions or comparisons of the strengths and limitations of the various assays are beyond the scope of this article. The reader is referred to Table 3 with test-specific information and references.

| Assay a | Vendor a | Polyclonal Versus IgG Specific | Principle | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asserachrom IgGAM | Diagnostica Stago | Polyclonal | ELISA | 100 | 64–86 |

| GTI PF4 IgG | GTI Diagnostics | IgG specific | ELISA | 100 | 42–96 |

| HemosIL AcuStar HIT-Ab (PF4-H) | Instrumentation laboratory | Polyclonal | Latex-enhanced immunoturbidimetric assay | 100 | 81 |

| HemosIL AcuStar HIT-IgG (PF4/H) | Instrumentation laboratory | IgG specific | Latex-enhanced immunoturbidimetric assay | 100 | 96 |

| ID-heparin/PF4 PaGIA | Diamed | Polyclonal | Particle gel immunoassay | 94–100 | 61–95 |

| Poly-ELISA | GTI Diagnostics | Polyclonal | ELISA | 100 | 81 |

| Zymutest HIA IgG | Hyphen Biomed Research | IgG specific | ELISA | 100 | 44–96 |

| Zymutest HIA IgGAM | Hyphen Biomed Research | Polyclonal | ELISA | 100 | 87 |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree