Borderline resectable pancreatic cancer represents a subcategory of advanced cancer that is typically defined by limited involvement of the major mesenteric vasculature. Such involvement is associated with a high likelihood of microscopically incomplete resection if surgery is used as the primary therapeutic modality. Increasing data support the role of neoadjuvant therapy as part of multimodality management but there is no uniformly accepted standard of care. This review discusses, based on recent literature and the experience of the Pancreatic Tumor Study Group at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, the classification, definition, diagnosis, and management of borderline resectable pancreatic cancer.

Key points

- •

Pancreatic cancers with borderline resectable anatomy are those at high risk for a microscopically positive (R1) resection when surgery is used as primary therapy.

- •

Local tumor anatomy is best assessed radiographically with high-quality computed tomography using a pancreatic protocol.

- •

Patients with clinical findings suggestive of metastatic disease or at high risk for pancreatic surgery also may be considered borderline resectable on the basis of nonanatomic parameters.

- •

Patients with borderline resectable pancreatic cancer should be treated with neoadjuvant therapy before planned surgical resection.

- •

Response to neoadjuvant therapy for pancreatic cancer is difficult to assess radiographically or serologically.

- •

Laparotomy with intent to resect the primary tumor should be performed for all patients with borderline resectable disease who have no evidence of disease progression and who have a performance status and comorbidity profile appropriate for major surgery after receipt of neoadjuvant therapy.

Introduction

A margin-negative resection of the primary tumor with a complete regional lymphadenectomy represents a necessary condition for cure of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). The staging designation “borderline resectable” has been historically used to characterize local tumor anatomy that confers high risk for a microscopically positive surgical resection and/or early treatment failure after an initial surgical approach. For this reason, borderline resectable disease has been considered an intermediate stage of disease on a spectrum of resectability delimited by “resectable” and “unresectable” PDAC.

Many definitions and criteria for this disease stage exist, however, and all have been used heterogeneously in the literature. Interpretation of existing data regarding diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes for patients with borderline resectable cancer is therefore difficult. Furthermore, no data from prospective trials have been generated to guide the evaluation, diagnosis, or management of patients with this stage of disease, so essentially all decision-making is directed by low-level data or consensus.

Herein we describe current thinking regarding the classification, definition, diagnosis, and management of patients with borderline resectable PDAC and discuss ongoing controversies relevant to this disease stage.

Introduction

A margin-negative resection of the primary tumor with a complete regional lymphadenectomy represents a necessary condition for cure of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). The staging designation “borderline resectable” has been historically used to characterize local tumor anatomy that confers high risk for a microscopically positive surgical resection and/or early treatment failure after an initial surgical approach. For this reason, borderline resectable disease has been considered an intermediate stage of disease on a spectrum of resectability delimited by “resectable” and “unresectable” PDAC.

Many definitions and criteria for this disease stage exist, however, and all have been used heterogeneously in the literature. Interpretation of existing data regarding diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes for patients with borderline resectable cancer is therefore difficult. Furthermore, no data from prospective trials have been generated to guide the evaluation, diagnosis, or management of patients with this stage of disease, so essentially all decision-making is directed by low-level data or consensus.

Herein we describe current thinking regarding the classification, definition, diagnosis, and management of patients with borderline resectable PDAC and discuss ongoing controversies relevant to this disease stage.

Definitions

Anatomic Staging (Borderline Resectable Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Type A)

It has long been recognized that the prognosis of patients who undergo surgical resection for PDAC is highly dependent on the histopathologic status of the surgical margins. Indeed, complete excision of the primary tumor to microscopically negative margins (R0 resection) is associated with the best postoperative outcome. In contrast, patients who undergo total gross excision but have histologically positive margins (R1 resection) have a shorter duration of overall survival in most series. Moreover, patients with gross residual disease (R2) after surgery have a prognosis similar to that of patients who do not undergo resection and are treated with palliative intent. For these reasons, the likelihood of attaining negative surgical margins is a critical consideration when determining whether or not a patient is a potential candidate for pancreatectomy. A precise assessment of resectability represents the most critical component of the pretreatment workup ( Table 1 ).

| Vessel | Potentially Resectable | Borderline Resectable | Locally Advanced |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMV-PV | TVI <180 | TVI ≥180 and/or reconstructible occlusion a | Unreconstructable occlusion |

| SMA | No TVI | TVI <180 | TVI ≥180 |

| CHA | No TVI | Reconstructible a , short-segment TVI of any degree | Unreconstructable TVI |

| Celiac trunk | No TVI | TVI <180 | TVI ≥180 |

a Normal vein or artery proximal and distal to the site of suggested tumor-vessel involvement suitable for vascular reconstruction.

As it was first described in the 1990s, borderline resectability was an anatomic designation that was used to describe tumors that appeared to involve the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) and/or portal vein (PV), hepatic artery, superior mesenteric artery (SMA), or adjacent organs on cross-sectional imaging, because resection of cancers involving these peripancreatic structures was typically complicated by high rates of positive margins, postoperative complications, disease recurrence, and early death. Today, most definitions for this stage of disease continue to focus on the radiographic extent of involvement of the major mesenteric vascular structures by tumor.

Two anatomic definitions of borderline resectable PDAC are most commonly used in the literature, and both are based on multidetector computed tomography (CT) images obtained before treatment: type A of the criteria put forward by investigators from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC), and criteria adopted at a consensus conference attended by members of the Americas Hepatopancreatobiliary Association (AHPBA)/Society of Surgical Oncology (SSO)/Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT) (and subsequently modified by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network [NCCN] ). Both of these sets of criteria designate tumors as resectable in the absence of evidence for significant mesenteric vein or arterial involvement, as borderline resectable in the presence of evidence for minor to moderate mesenteric venous or arterial involvement, and as unresectable in the presence of evidence for unreconstructable mesenteric venous occlusion or significant arterial involvement.

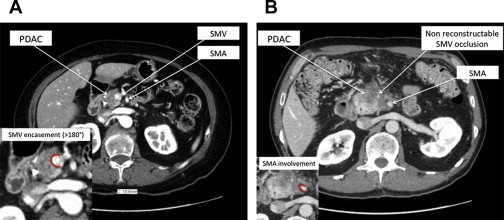

In 1997, Lu and colleagues, reported that a radiographic interface between a primary pancreatic tumor and an adjacent vessel measuring at least 180° of the vessel’s circumference was a specific indicator of necessitating resection of the vessel to remove the tumor. Recent studies using accurate imaging protocols have corroborated this observation. Furthermore, attempts at resection and reconstruction of the superior mesenteric artery or celiac trunk have been associated with high rates of perioperative morbidity and low rates of long-term survival, but surgical results with hepatic arterial resection have been more favorable. Finally, tumors that narrow the SMV and/or PV unilaterally have been associated with a more favorable disease-specific survival than tumors that narrow the vein bilaterally or occlude it. These data suggest that tumors that infiltrate the left side of the SMV-PV toward the SMA have a higher likelihood of a margin-positive resection and poor outcome following pancreatectomy whether or not concomitant venous resection is performed.

Based on these data, and in an attempt to standardize the language used to describe borderline resectable cancers, investigators from the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology, the Southwest Oncology Group, the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, and the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group have proposed a comprehensive classification system that was used in the Alliance Trial A021101. This classification system recognizes any one or more of the following as radiographic identifiers of borderline resectable PDAC:

- •

An interface between tumor and the SMV/PV measuring 180° or greater of the vessel wall circumference, and/or reconstructible venous occlusion;

- •

An interface between tumor and the SMA measuring less than 180° of the vessel wall circumference;

- •

A reconstructible, short-segment interface of any degree between tumor and the common hepatic artery; and/or

- •

An interface between tumor and the celiac trunk measuring less than 180° of the vessel wall circumference.

Anatomic, Biologic and Physiologic Criteria for Borderline Resectable Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma

In practice, the exclusive use of anatomic definitions of resectability have limited value with regard to estimating prognosis among patients with localized PDAC because each anatomically defined stage actually includes a clinically heterogeneous population within it. Indeed, more than 50% of patients with resectable cancers are unable to undergo surgery at all, and the survival duration of inoperable patients with resectable cancers is similar to that of patients with metastatic disease. Moreover, although the rate of 5-year survival is approximately 30% among patients who complete multimodality therapy including resection, recurrence within the first 2 years occurs in more than 50% of resected patients. Thus, no existing anatomic staging systems can adequately identify patients most appropriate for surgery because those systems focus exclusively on resectability of the tumor as opposed to operability of the patient.

In an attempt to identify patients with primary tumor anatomy, cancer biology, or patient physiology that places them at the limits of compatibility with favorable results after potentially curative therapy including surgery, we have proposed 2 additional subsets of patients who often escape accurate classification into a specific stage of disease : patients with suspicion for metastasis and patients with a suboptimal performance status or extensive medical comorbidities requiring prolonged evaluation or optimization. Inclusion of these latter 2 groups into the borderline resectable category allows for accurate staging of all patients who present with newly diagnosed pancreatic cancer. The MDACC criteria thus add to the anatomic (Type A) criteria described previously with 2 additional sets of criteria for Type B and Type C borderline resectable PDAC, as described in the following sections.

Borderline Resectable Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma (Type B)

Rapid recurrence of cancer after resection is frequently observed, whether or not patients receive adjuvant therapy. This observation highlights both the prevalence and clinical significance of the preexisting micrometasases, and/or undetected or incompletely treated disseminated cancer cells that exist in most patients with radiographically localized PDAC. Indeed, one of the main concerns in treating patients with PDAC surgically is the risk of early recurrence following complete resection of the primary tumor.

Based on our initial definition and the recent literature, patients with borderline resectable type B PDAC have resectable or borderline resectable (Type A) tumor anatomy in association with clinical findings suspicious but not diagnostic for extrapancreatic disease. Such findings might include radiographically indeterminate liver lesions or distant lymph nodes, a biopsy-proven involvement of regional lymph node, or a serum carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19-9 level greater than 1000 units/mL (with a normal total bilirubin); any and all of these findings suggest a particularly high risk for early treatment failure when surgery is used as primary therapy.

Borderline Resectable Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma (Type C)

The risks and benefits of surgical resection must be critically evaluated in the context of a cancer that has a particularly poor prognosis regardless of the therapeutic approach initially chosen. Moreover, to the extent that postoperative complications are associated with a reduction in patients’ likelihood of receiving adjuvant therapy and the duration of their survival, the performance of immediate pancreatectomy should be discouraged among patients at particularly high risk for surgery.

Using our definition, patients with borderline resectable PDAC are those with a marginal performance status or a severe preexisting comorbidity profile (including advanced age) that put them at high risk for a major surgical procedure. Although historically this has been a relatively subjective assessment, useful tools now exist with which a personalized assessment of risk based on age, comorbidities, and frailty can be calculated. Patients with type C should be managed actively in a multidisciplinary group of expert physicians, including a dedicated pancreas program dietician, physical therapist, and members of the internal medicine faculty to appropriately risk stratify and optimize each patient for eventual surgery.

Diagnosis and staging

Computed Tomography and MRI

The characteristics used to define resectable, borderline resectable, and unresectable disease anatomically are based on the use of cross-sectional imaging and require the use of imaging techniques that optimize the visualization of tumor, its relationship to adjacent anatomic structures, and its possible spread to nodes outside the surgical field and/or distant sites, such as the liver, peritoneum, lung, and bone.

The NCCN guidelines recommend pancreas-specific CT or MRI be performed for all patients with localized PDAC. CT and MRI constitute the most commonly performed primary investigations used for the diagnosis and staging of pancreatic cancers, and they have equivalent accuracy with regard to the assessment of vascular involvement and resectability. The studies generally can be used interchangeably ; the choice between CT or MRI should be determined by the availability of both the individual modality as well as the technical expertise in reading and reporting their results. MRI is more expensive and less available when compared with CT. Furthermore, the ability of most surgeons to interpret CT images is superior than their ability to interpret MRI. Thus, MRI is typically used as a secondary modality when CT cannot identify or characterize the pancreatic mass, when an indeterminate liver lesion exists, or in the presence of a CT contrast allergy.

Because the evaluation of resectability on cross-sectional imaging currently involves determining in cross section the degrees of circumferential involvement of regional arteries and veins by tumor and narrowing/occlusion of veins, CT angiography (preferably 16–detector row or greater) is the generally preferred staging modality. The most commonly used CT protocol is a biphasic examination, with preferably submillimeter sections (0.5–1 mm). The pancreatic phase is obtained approximately 40 to 50 seconds after the administration of intravenous contrast (preferably using high iodine concentration of at least 300 mg iodine/mL and at a relatively rapid rate of injection at 3–5 mL/s). In this phase, the pancreatic parenchyma enhances maximally, producing the highest contrast difference between the optimally enhanced pancreatic parenchyma and the usually hypodense pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. The peripancreatic arteries are usually well opacified in this phase allowing for their concomitant evaluation. The second acquisition is obtained in the portal venous phase, approximately 65 to 70 seconds after contrast administration. In this phase, the portomesenteric vessels are usually well opacified, allowing for better evaluation of the venous system. The hepatic parenchyma, a common site of metastasis, is also optimally enhanced in the portal venous phase allowing detection of metastatic deposits that are typically hypodense. The administration of positive oral contrast can affect the postprocessing of the CT examination and the generation of the volume-rendered images. A neutral or low Hounsfield units oral agent is preferred.

Endoscopic Ultrasonography

Among the available imaging tools, endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) has emerged as a useful modality in the diagnosis of pancreatic tumors because of its ability to facilitate the acquisition of tissue biopsies with fine-needle aspiration. But the role of EUS in staging is not clear. Indeed, in a systematic review of the literature, heterogeneous study designs, quality, and results have been reported and no definitive conclusions could be made. Moreover, EUS is invasive and operator dependent. EUS thus serves as a complementary staging investigation to cross-sectional imaging with CT or MRI.

Radiologic Reporting

Accurate anatomic staging of localized PDAC at the time of presentation may maximize the survival benefit for patients in whom complete resection can be achieved and minimize the morbidity from unnecessary laparotomy or major surgery in patients with high risk of residual disease after resection. The use of standardized descriptions of radiographic anatomy, as might be used in templated radiology reports, also can help to facilitate research and allow for comparison of stage-specific treatment results between different institutions. Reporting of the imaging findings for patients with pancreatic cancer should include descriptions of the primary tumor’s size and location, the extent of the circumferential interface (tumor-vessel interface) between the tumor and major vessels (in degrees), the presence or absence of vessel occlusion, variant vascular anatomy, an anatomic assessment of local tumor resectability (resectable, borderline resectable [ Fig. 1 A], or locally advanced [see Fig. 1 B]), and extent and location of extrapancreatic disease.