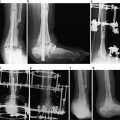

Fig. 38.1

Female, Asian, 68 years old, type 2 diabetes for at least 15 years, visual acuity: 20/400 OD and 20/200 OS. The dilated eye exam revealed clinically significant diabetic macular edema (CSME) OD >OS. Fundus color picture, OD(A) and OS(B) on the first visit (note the hemorrhages, few LASER spots, and posterior pole hard exudates—CSME). Fundus color, OD(C) and OS(D) after 10 months of treatment (note the absence of hemorrhages and hard exudates and more LASER scars). Baseline OCT OD(E1) (note the central retina diabetic edema); OCT OD(E2) after one intravitreal Ranibizumab injection; OCT OD(E3) after six Ranibizumab injections (note the normal anatomy aspect). Baseline OCT OS(F1) and OCT OS(F2) after one intravitreal Ranibizumab injection, OCT OS(F3) after three Ranibizumab injections (note the normal anatomy aspect). Final vision after 10 months was 20/40 for both eyes

It is estimated, in another study, that each year 63,000 new cases of PDR arise in the USA, among these 29,000 cases of high-risk PDR. Regarding macular edema, 80,000 new cases are expected, 56,000 being cases of CSME, and 12,000–24,000 new cases of legal blindness occur each year as a result of DR [17, 19, 24].

The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) showed that the rates of DR development and progression were significantly reduced after 3 years of intensive insulin therapy. The effect of reducing the HbA1c from 9.1 to 7.3 % resulted in benefit maintained through the 7 years of follow-up. The progression rate to complications at the end of the DCCT remained lower in the intensive treatment group, although the costs of intensive care are three times the values of conventional therapy [17, 25–28].

Nevertheless, with appropriate medical and ophthalmologic assistance, over 90 % of visual loss cases resulting from the PDR could be prevented. Therefore, until DM cure is discovered, the emphasis should be on clinical care to prevent vision loss, early diagnosis, correct classification (Table 38.1), and appropriate treatment [29–33].

Nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR) | |

Mild | At least one microaneurysm or mild level of microaneurysms and retinal hemorrhage |

Moderate | Moderate level of microaneurysms and retinal hemorrhage and/or mild levels of cotton wool spots, venous beading, and IRMA |

Severe | Severe intraretinal hemorrhages and microaneurysms in all four quadrants, and/or venous beading in two or more quadrants, and/or moderate IRMA in at least one quadrant |

Proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) | |

Early | NVD or NVE, less severe than high-risk PDR |

High risk | NVD ≥1/3 optic disc area, any NVD with vitreous hemorrhage, and/or NVE ≥1/2 optic disc area and preretinal or vitreous hemorrhage |

Advanced | Posterior fundus obscured by preretinal or vitreous hemorrhage or center of macula detached |

Clinically significant macular edema (CSME) | Retinal edema located at or within 500 μm of the center of the macula |

Hard exudates at or within 500 μm of the center with thickening of adjacent retina | |

A zone of thickening larger than one optic disc area if located within one disc diameter of the center of the macula | |

Key Points to the Diagnosis

Because DR has few symptoms until vision loss develops, regular screening is critical. A complete ocular evaluation by a retina specialist ophthalmologist is mandatory to diagnose and treat the DR [34, 35].

During the exam the ophthalmologist will test the vision, take eye pressure measurements and under dilated eye exam—the best way to diagnosed DR, the following will be checked: presence of a cataract, abnormal blood vessels, retina swelling, blood or fatty deposits (hard or soft exudates) in the retina, new blood vessel growth, scar tissue, optic nerve abnormalities, vitreous hemorrhage, vitreoretinal tractions, and retinal detachment [35].

Ancillary tests may be useful to achieve a correct diagnosis and treatment plan, for example the fluorescein angiography (FA) and the optical coherence tomography (OCT).

The FA consists in a sequence of, nowadays, digital picture frames before and after a venous dye (fluorescein) injection. FA is especially useful in the management of DR because it provides information on the retinal circulation and on the status of the blood-retinal barrier. FA is also important to determine the degree of ischemia or the presence of retinal vascular abnormalities [36–38].

OCT, also called “optical biopsy,” is an imaging technique that produces high-resolution cross-sectional images of the retina; the “in vivo slide” shows the thickness of the retina and its layer details. FA and OCT exams are used during the follow-up to monitor how treatment is working as well [36–38].

Differential Diagnosis

Diagnosing DR is the daily work of the retinal specialty. However it is necessary to consider other etiologies in the differential diagnosis, especially in the presence of a negative work-up for diabetes.

The DR is the most common retinal vascular disease and its differential diagnosis must be made with other ocular vascular disorders such as hypertensive retinopathy, central or branch retinal vein occlusion, arterial occlusive disease, vasculitis, macroaneurysm, other types of macular edema, hemoglobinopathies, retinal telangiectasias, sickle cell disease, valsalva retinopathy, radiation retinopathy, ocular ischemic syndrome, Terson syndrome, and Purtscher retinopathy.

Other less frequent conditions need to be investigated as well in some individuals such as infectious etiologies (e.g., HIV, CM), inflammatory and autoimmune diseases (e.g., lupus erythematosus), cancer and paraneoplastic retinopathies (e.g., leukemia, lymphoma), muscular dystrophies, phakomatoses, and toxicity (e.g., some drugs) among others.

Present and Future Therapies

The appropriate clinical management of diabetic retinopathy was defined by the results of several large randomized clinical trials. These studies have elucidated the DR progression rates, follow-up intervals, and effectiveness of glycemic control and laser photocoagulation, considered the golden standard treatment. They also established recommendations for vitrectomy surgery [39–43].

The presence of CSME and high-risk PDR is an indication for immediate treatment. The first treatment option is the LASER; focal or grid LASER is used for macular edema and a panretinal photocoagulation is performed for high-risk PDR cases. Vitrectomy surgery will probably be the choice in cases of PDR associated with tractional and/or rhegmatogenous retinal detachment and long-standing vitreous hemorrhage, where posterior pole retina visualization is poor [39–43].

Considerable progress has been made in the delivery of ophthalmological care for DR over the past decade [44]. Regarding how to perform LASER treatment, great changes have happened such as new LASER wavelengths, pattern scan laser photocoagulator devices, better-view systems, micropulse LASERs, and computer-guided navigated retinal photocoagulation delivery [45, 46].

In recent years, important advances in pharmacotherapy have shown promising results in the treatment of DR, such as the corticosteroids in special triamcinolone acetonide, the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) antagonists—specially the FDA-approved Ranibizumab (Lucentis®, Genentech, Inc.), Bevacizumab (Avastin®, Genentech Inc.), and Aflibercept (EYLEA®, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals), and some other drugs like Infliximab (Remicade®, Centocor), Etanercept (Enbrel®, Amgen, Inc. and Wyeth), Vitrase (hyaluronidase ovine, ISTA Pharmaceuticals, Inc.), Octreotide (Sandostatin®, Novartis), and Ruboxistaurin (Arxxant®, Eli Lilly and Company), among others [47–52].

In conclusion, the DR prevention relies initially in the treatment or the cure of the underlying disease, DM, but it remains a challenge to medicine. However, a strict control of glucose levels should be the primary concern. Once installed the DR complications “a war starts” and action is required; laser therapy and some drugs, if indicated, are the weapons to be used in order to preserve the best possible visual acuity.

References

1.

Ali MK, McKeever Bullard K, Imperatore G, et al. Characteristics associated with poor glycemic control among adults with self-reported diagnosed diabetes–National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, United States, 2007–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61 Suppl:32–7.PubMed

2.

3.

Zhang X, Saaddine JB, Chou CF, et al. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in the United States, 2005–2008. JAMA. 2010;304(6):649–56.PubMedCrossRef

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree