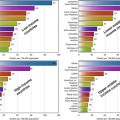

Fig. 6.1

Age-wise prevalence of diabetes

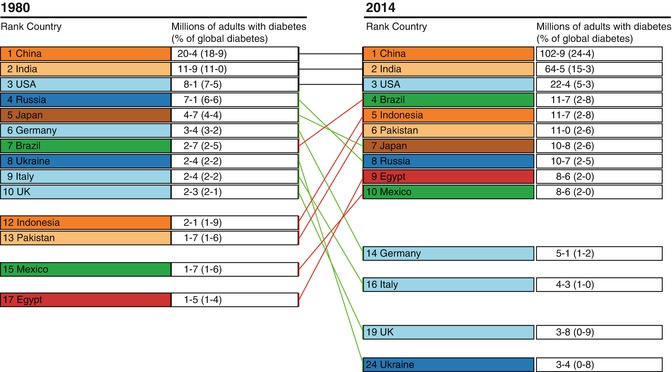

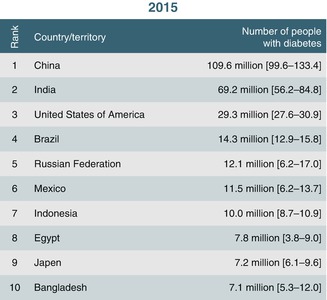

With an estimated 69.2 million people suffering from the condition, the largest in any country in the world, diabetes has become a major health-care problem in India (refer to Figs. 6.2 and 6.3). Recent epidemiological studies from India point to the great burden due to diabetes and its micro- and macrovascular complications. This is primarily because the status of diabetes control in India is far from ideal. Based on the available data, the mean glycated haemoglobin levels are around 9 % which is at least 2 % higher than the goal currently suggested by international bodies. A balanced approach to improve awareness about diabetes and its control both amongst patients and the medical fraternity is an urgent need of the hour in India.

Factors Contributing to the Rapid Increase in Prevalence of Diabetes in Asia

Although ageing, urbanisation and associated lifestyle changes are the major determinants for the rapid increase, an adverse intrauterine environment and the resulting epigenetic changes could also contribute in many developing countries. More action is required to understand the drivers of the epidemic to provide a rationale for prevention strategies to address the rising global public health ‘tsunami’.

Urbanisation and Socioeconomic Transition

Diabetes burden in India is contributed by various factors. Genetic predisposition combined with lifestyle changes, associated with urbanisation and globalisation, contributes to this rapid rise of diabetes in India. The highest rates of urbanisation have been in Singapore, Korea, Malaysia, the Philippines and Indonesia (50 %). China, Pakistan, India and Thailand have intermediate rates (30 %) and Bangladesh and Sri Lanka have slow rates of urbanisation. The increase in urban population and ageing are the main determinants of the global rise in the prevalence of diabetes. Urbanisation and internal rural to urban migration result in several adverse impacts: physical activity decreases, diet habits shift towards high-energy foods and body mass index (BMI) and upper body adiposity increase considerably. The Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) study done in the 1970s reported a prevalence of 2.3 % in urban areas which has risen to 12–19 % in the 2000s. Correspondingly, in rural areas, prevalence rates have increased from around 1 to 4–10 % and even 13.2 % in one study. Thus it is clear that both in urban and rural India, prevalence rates of diabetes are rising rapidly with a rough urban–rural divide of 2:1 or 3:1 being maintained through the last two to three decades with the exception of Kerala where rural prevalence rates have caught up with or even overtaken urban prevalence rates. The postulates from the ICMR–INDIAB study predicted for the burden of diabetes which projected that in 2011, India would have 62.4 million people with diabetes and 77.2 million people with prediabetes.

Age

As compared to Western populations, Asian Indians develop diabetes at a younger age with more prevalence at the age of 60–69 years, whereas in the Chinese population, it peaks at 79–89 years. Indians also have a higher prevalence of impaired glucose tolerance at a younger age than the Chinese population. The findings from Pakistan and Sri Lanka also show similar results.

Anthropometry: Thin-Fat Phenotype

It is observed that amongst Asians, diabetes occurs at lower body mass index (BMI) levels than in Western populations, and small increments in weight trigger glucose intolerance in susceptible subjects. Especially Asian Indians have higher odds of developing diabetes, despite having a significantly lower BMI than the white population.

Several studies in Asian populations, particularly in Asian Indians, have highlighted the ‘metabolically obese’ phenotype amongst normal weight individuals. This phenotype, characterised by greater abdominal obesity despite a normal BMI, less muscle mass, higher percentage of body fat and increased propensity for insulin resistance compared with the Western population, renders higher susceptibility for diabetes in Asian populations.

The association of BMI and diabetes is well established and is usually modified by ethnicity. Ethnicity factors that contribute are genetic constitution, lifestyle, living environment and anthropometric characteristics. Body composition related to fat distribution is a stronger determinant of the metabolic milieu than BMI. The diabetes epidemiology, collaborative analysis of diabetes criteria in Europe/in Asia study group noted that the overall effect of age on the prevalence of diabetes differed considerably between the ethnic groups, even in the subjects with the same BMI. Asian populations are prone to have more intra-abdominal fat accumulation and low muscle mass. Asian Indians, in particular, have the above abnormalities which account for the high prevalence of insulin resistance and diabetes at low levels of BMI. The risk of diabetes increases progressively from a BMI of ≥23 kg/m2 amongst Indians. BMI in ≥ of 23 kg/m2 is also considered overweight for most Asian populations. Asian Indians have small body size which has been named as ‘thin-fat Indian’. Asian Indians have thinner limbs, which are suggestive of smaller muscle mass. However, despite their thinness, they are centrally obese, with higher waist–hip ratio (WHR) and higher subscapular–triceps skinfold ratio than their British counterparts. Many studies show that Asian Indians have more body fat for any given BMI compared with Caucasians and black Africans. Indians also have higher levels of central obesity (measured as waist circumference [WC], WHR, visceral fat and posterior subcutaneous abdominal fat). This is reflected in higher plasma nonesterified fatty acid (NEFA) and triglyceride concentrations, hyperinsulinaemia with fasting as well as post-glucose challenge states and higher insulin resistance. Thus, Asian Indians have an unusual thin-fat body composition associated with the insulin resistance syndrome, and this is the now popular ‘thin-fat Indian’ concept.

Smoking and Alcohol Use

Smoking increases the risk of central obesity and insulin resistance and the risk of diabetes is shown to be higher by 45 % in smokers than amongst nonsmokers. The increasing use of alcohol in Asian countries, especially amongst the middle class and rural population, also increases the risk for diabetes and other metabolic diseases and deleterious health effects.

Genetic Susceptibility

The genetic burden on Asian Indians makes the population more susceptible to diabetes. This risk is further increased due to interaction with environmental triggers. Exposure to a high fat diet and lower levels of physical activity trigger the gene–environmental interaction. Both the thrifty genotype and thrifty phenotype hypotheses appear to be the aetiology. The selective presence of ‘thrifty genotypes’ has been considered to be advantageous in certain populations during evolutionary selection by repeated famine and feast cycles. However, these genes have rendered them highly predisposed to obesity and diabetes during the modern era of continuous feasting. On the other hand, the ‘thrift phenotype’ hypothesis postulates that intrauterine malnutrition leads to metabolic and structural changes in the beta cells that are beneficial for early survival, but increases the risk of T2D and other chronic disorders in adulthood.

Screening

The prevalence of the micro- and macrovascular complications also influences the mortality rate due to diabetes. Unfortunately, more than 50 % of individuals with diabetes in India remain undiagnosed, and some may even present with macrovascular disease (coronary artery disease and cerebrovascular disease or stroke and peripheral vascular disease) and microvascular disease (retinopathy, nephropathy and neuropathy) at the time of diagnosis.

Data on various complications of diabetes have also been published by several authors. However, till recently, most of such data were hospital or clinic based and therefore subject to referral bias. The Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiology Study (CURES) and the Chennai Urban Population Study (CUPS) provide the first population-based data from India on virtually all complications of diabetes. CURES was a population-based study involving 26,001 participants aged 20 years or above based on a representative population of Chennai. The overall prevalence of diabetic retinopathy based on four-field stereo colour retinal photography was 17.6 %. The prevalence of overt nephropathy was 2.2 % while that of microalbuminuria was 26.9 %. Peripheral neuropathy based on biothesiometry was detected in 26.1 %.

In the CUPS study, coronary artery disease was evident in 21.4 % of diabetic subjects, 14.9 % of subjects with impaired glucose tolerance and in 9.1 % of people with normal glucose tolerance. In the same study, peripheral vascular disease was present in 6.3 % of diabetic subjects compared to 2.7 % amongst nondiabetic subjects. Diabetic subjects also had increased subclinical atherosclerosis as measured by intimal-medial thickness at every age point, compared to their nondiabetic counterparts. Assuming that 40 million people in India have diabetes, this translates to at least 7 million with retinopathy, 0.8 million with nephropathy, 10.4 million with neuropathy, 8.5 million with CAD and 2.5 million with PVD. Thus, the burden due to diabetic complications is very high in India due to the sheer number of people with diabetes. These figures are in fact very conservative, and it is possible that in rural areas, the prevalence of complications is much higher because of poorer control of diabetes and lack of access to healthcare.

Identifying accurate and low-cost screening methods is a necessary first step in assessing the cost-effectiveness of screening to detect undiagnosed diabetes. Indian Diabetes Risk Score (IDRS) is more effective and significantly less expensive for screening for undiagnosed T2DM compared to genotyping TCF7L2 SNPs, the strongest genetic marker for T2DM currently available. Using IDRS screening prior to OGTT reduces costs while still detecting a substantial portion of NDD individuals. A potential additional benefit of both the IDRS and genotyping is their ability to identify individuals who currently do not have diabetes but are at high risk of developing diabetes in the future. Thus an individual with an IDRS score of ≥60 at baseline was three times more likely to develop diabetes in the future than low-risk subjects (IDRS <30).

Awareness of Diabetes in India

The awareness of diabetes is a cornerstone of the prevention of this disease. CURES reported that nearly 25 % of the population was unaware of diabetes. Only around 40 % of the participants felt that the prevalence of diabetes was increasing, and only 22.2 % of the population and 41 % of known diabetic subjects felt that diabetes could be prevented. Though the awareness levels increased with education, only 42.6 % of postgraduates and professionals, which group included doctors and lawyers, knew that diabetes was preventable. The knowledge of risk factors of diabetes was even lower with only 11.9 % of the study subjects reporting obesity and physical inactivity as risk factors for diabetes. More alarming was the fact that even amongst known diabetic subjects, only 40.6 % were aware that diabetes could lead to some organ damage. There is another population-based study which was done to find out the levels and details regarding awareness on diabetes in urban adult Indian population aged ≥20 years. The knowledge regarding the causes of diabetes, its prevention and the methods to improve the health was significantly low amongst the general population. In the total study group, 41 % were unaware of the health being affected by diabetes, and only less than 30 % knew about the complications related to kidneys, eyes and nerves. Many persons with diabetes (46 %) felt it was a temporary phenomenon. Amongst the diabetic subjects, 92.3 % had sought the help of a general practitioner to take treatment. Only a small proportion went to a specialist.

Current Status of Diabetes Control in India

The next challenge in India is that the quality of diabetes care varies considerably depending upon the awareness levels, expertise available, attitudes and perceptions amongst diabetes care providers. An estimate based on sales of antidiabetic pharmaceutical agents shows that on an average only 10–12 % of people with diabetes receive modern pharmacological treatment in India. In 1998, the Diabcare–Asia study was carried out to investigate the relationship between diabetes control, management and late complications in a subset of urban Indian diabetes population treated at 26 tertiary diabetes care centres. A total of 2,269 patients participated in this study and it was observed that approximately half of the patients had poor control (HbA1c >2 % points above upper limit of normal), and the mean HbA1c was significantly higher (8.9 ± 2.1 %) than the levels recommended by the American Diabetes Association and the ICMR guidelines in India. Over 54 % of patients had diabetes-related complications. The mean HbA1c levels and frequency of complications were higher in patients with longer diabetes duration. This study also showed that 4 % of patients were on diet therapy, 53.9 % were receiving oral antidiabetic agents (OHAs), 22 % were receiving insulin and 19.8 % were receiving a combination of insulin and OHAs. This study concluded that with increasing duration of diabetes, glycaemic control deteriorates leading to late complications. It also confirmed that diabetes care in India leaves much to be desired and suggested the need for efforts to increase awareness amongst health professionals to improve diabetes care in India.

Non-pharmacologic Approach for the Management of Diabetes

Lifestyle modifications are the cornerstone of management of diabetes mellitus and include the prescription of a healthy diet, regular exercise, the management of stress and avoidance of tobacco. The aims of dietary management are to achieve and maintain ideal body weight, euglycaemia and desirable lipid profile, to prevent and postpone complications related to diabetes and to provide optimal nutrition during pregnancy, lactation, growth, old age and associated conditions, e.g. hypertension and catabolic illnesses. Recently the published STARCH study shows that Indians consume high carbohydrate in their diet compared to the Western population. The comparison of macronutrients (i.e. region-wise carbohydrate, fat and protein) revealed a similar pattern of dietary consumption, that is, high carbohydrate and a lower range of fat and protein. This study neutralises the myth that only the south Indian population consumes high carbohydrate in their diet (rice, idli, etc.). Dietary transition and a sedentary lifestyle have led to an increase in obesity and diet-related non-communicable diseases like T2DM, cardiovascular disease, etc. predominantly in urban, but also in rural areas. The dietary recommendations should be individualised according to the person’s ethnicity, cultural and family background and personal preferences and associated comorbid conditions. It should be flexible in a variety and preparation of food choices and timing of meals according to the person’s daily routine. Both the National Institute of Nutrition and expert group [2] have developed some broad Indian guidelines which recommend reduction intake of carbohydrate, higher intake of fibre, lower intake of saturated fat, optimal ratio of essential fatty acids, slightly higher protein intake, lower intake of salt and restricted intake of sugar.

The role of regular physical activity is well established in the management in persons with type 2 diabetes. A careful assessment of an individual should be made by the physician while incorporating an exercise programme in the management. Exercise programme should be individualised according to the individual capacity and disabilities. The person with diabetes must wear appropriate footwear.

‘Clinical Inertia’ in Diabetes: Failure to Achieve Tight Control

Failure of initiation of or intensification of therapy, when indicated, is termed ‘clinical inertia’. Though we have well-defined management goals, effective therapies and practice guidelines, there is often a failure to take appropriate action despite recognition of the problem. This is a common problem in the management of patients with asymptomatic chronic illnesses. The use of ‘soft’ reasons to avoid intensification of therapy and lack of education, training and practice organisation aimed at achieving therapeutic goals are the common reasons for clinical inertia. Clinical inertia in achieving glycaemic targets in Indian diabetic subjects could be expected to be even more than in the West, where it has been reported that 65 % of the patients diagnosed with diabetes, only 73 % are prescribed pharmacologic therapy and only 33 % of those treated achieve a haemoglobin A1C value of less than 7 % by the ADA goal. This may be due to the low rates of awareness of diabetes and its complications in India resulting in poor glycaemic control seen in Indians with diabetes. Moreover, other factors like poverty, lack of accessibility to health services and inadequate follow-up are additional factors in developing countries like India.

Consequently, insulin is delayed until it is absolutely necessary. Most patients are initiated on insulin after a course of multiple oral antidiabetic drugs. Insulin therapy is initiated only when the HbA1c levels had deteriorated further to around 9 %. Physicians often delay insulin therapy worrying that the daily injections, modification of lifestyle due to insulin and dependence on insulin for life and that patients may feel that insulin therapy indicates the last stage of diabetes. However, patients who had moved on to insulin seemed to have a more positive approach towards his/her treatment due to the improvement in quality of life and better control despite the issues outlined above.

Pharmacologic Therapy in Diabetes: Is It Different?

A proactive approach to treating type 2 diabetes is recommended: therapy should be individualised with early consideration of combination therapy and ongoing reinforcement of lifestyle modification messages. Indeed, the conservative stepwise approach to type 2 diabetes management involves lifestyle modification, followed by treatment with a single oral antidiabetic agent, often up-titrated to maximal recommended doses before combination therapy is introduced. Very often there is a delay between stepping up from monotherapy (e.g. metformin alone) to combination therapy (e.g. metformin plus other OADs, often sulphonylurea), and this can result in unacceptable delays in achieving and maintaining glycaemic goals with the potential for long periods of hyperglycaemia. Periods of hyperglycaemia long or even short can increase the risk of micro- and macrovascular complications. The current understanding of the complex pathophysiology of the disease and the progressive deterioration in glycaemic control over time supports the philosophy of earlier intervention with a more comprehensive initial therapy. The major classes of antidiabetic agents that may be combined with metformin include sulphonylurea (SU), thiazolidinedione (TZD), dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor (DPP4-i), insulin and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist. Few studies have investigated the effect of metformin-based early combination therapy. There are several different types of insulin available, but as a minimum, regular quick-acting human insulin and longer-acting NPH insulin should be available to everyone in all parts of the world.

In India, which is a resource-limited country, all therapies are available and it is a predominantly non-reimbursed market. Usually sulphonylureas, metformin, alpha glucosidase inhibitors and glitazone form the cornerstone of therapy with insulin. However, recently gliptins including the low-cost one as well as SGLT2 inhibitors are also available. Biosimilar insulin is also available but not popular and premixed insulin is still used widely. Cost and dose play a role in resource-limited environment. Indian usually requires lower doses and is more insulin resistant.

Translating Primary Prevention of Diabetes

The Indian Diabetes Prevention Programme (IDPP) has been a unique prospective study which has provided several pathways and strategies for the prevention of diabetes in India including the importance of the lifestyle modification and metformin which independently could reduce the incidence of diabetes in Asian Indians with impaired glucose tolerance. Also, these have been proposed as the cost-effective benchmarks amongst high-risk individuals with high degree of insulin resistance and may be useful in other developing countries as well. It is important to control the persistent IGT as it is demonstrated to add to the higher incidence of diabetes with other risk factors for diabetes, such as high BMI, waist circumference and body fat percentage. In a recent collaborative work across South Asia, Latin America and South Africa to compare the prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of diabetes and assess the relationship between diabetes and prediabetes with known cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors, it has been demonstrated that propensity for South Asians to develop diabetes and prediabetes at a younger age and lower body mass index compared with individuals from other low- and middle-income countries. Therefore, it is important that the long-term impact and the complications are prevented, and the health systems and policy makers must make concerted efforts to improve diabetes prevention and detection in the targeted population. Ramachandran A et al. have suggested that it is important to develop precise predictors for incident diabetes amongst Asian men. The analysis of the data from the combined cohorts of the Indian Diabetes Prevention Programmes 1 and 2 demonstrates that the baseline HbA (1c) was highly predictive of future diabetes in Asian Indian subjects with impaired glucose tolerance and nearly 60 % of the incidence occurred with values ≥6.0. Diagnostic sensitivity of ≥6.5 % for new diabetes was only 51 % using the oral glucose tolerance test as the standard for comparison. The combination of gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) and fasting plasma glucose (FPG) offers a simple and sensitive tool to identify subjects at high risk of developing diabetes. Similarly, several other markers including adiponectin, IL-6, retinol-binding protein 4, and hypertriglyceridaemic waist phenotype have been proposed to independently associate with incident diabetes. Prospective, intervention studies have demonstrated that increased compliance to lifestyle goals especially with the modification of the diet habits, independent of the physical activity, could result in the decrease in the incident of prediabetes. The mechanistic insights now ascribe these benefits through improvement in insulin sensitivity and beta-cell preservation. Prospective, parallel-group, randomised controlled trial across close to 9,000 subjects have demonstrated that mobile phone messaging is an effective and acceptable method to deliver advice and support towards lifestyle modification to prevent type 2 diabetes in men at high risk. Evidence from the DPP, and other prevention trials conducted in patients with prediabetes, shows that appropriate lifestyle modification including physical activity could lead to risk reduction in the incidence of T2DM by almost 58 %. Studies have shown that resistance and aerobic exercise is effective in improving metabolic profile of adults with T2DM. Previous research has reported improved insulin sensitivity/resistance and reductions in hyperglycaemia-related medications as a result of exercise training. In particular, supervised resistance training (max. ten repetitions for >3 days per week) has been shown to lead to significant improvement in insulin sensitivity and values of glycosylated haemoglobin, lipid profile and truncal and peripheral subcutaneous adipose tissue in Asian Indians with T2DM. It has been reported that children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes should complete a minimum of 30–60 min of moderate-intensity physical activity daily. Additional physical activity beyond 60 min/day would be helpful in maintaining glycaemic profile for T2DM patients. The practice of yoga is a traditional Indian practice that helps therapeutically and promotes physical and mental health. Yoga-based lifestyle modification programme helps in the reduction of blood glucose, HbA1c, triglycerides, total cholesterol and VLDL. Mindfulness eating and yoga exercise had health benefits on glycaemic control in pregnant women with GDM in some studies. Yogic exercises have enhanced the antioxidant defence mechanism in diabetics by reducing oxidative stress. Unless drastic steps are taken through national prevention programmes to curb the escalating trends in all of the countries, the social, economic and health-care challenges are likely to be insurmountable.

Organising and Conducting Diabetes Research in the Region

RSSDI (Research Society for the Study of Diabetes in India) is the largest organisation of diabetes health-care professionals and researchers in Asia, which was formed in 1972. Currently, there are more than 5,500 life members from across the country representing 29 Indian states and Union territories. Every year, RSSDI organises the national annual meeting, which not only provides a platform for its members to listen to the leaders in the field of diabetes from within the country as well as from abroad but also to interact amongst themselves and exchange knowledge and ideas. Annual meetings of RSSDI have been a regular feature for more than four decades and are very well attended. RSSDI has a nationwide presence through its 14 state chapters. All state chapters carry on the work of RSSDI at the state and local level. In addition, these chapters carry out independent activities including CMEs for member physicians, local research grants and awareness programmes for public as well as diabetes patients. RSSDI regularly publishes a newsletter, both in print and electronic format, which serves as an important link between the national body and its membership to keep the members informed of various activities, research grants and educational initiatives. The International Journal of Diabetes in Developing Countries (IJDDC) is the prestigious indexed publication of RSSDI and is an important resource of research work done in the field of diabetes in India. RSSDI funds research proposals from Indian scientists interested in conducting research in the field of diabetes mellitus. For providing research grants, RSSDI invites proposals from Indian scientists interested in conducting original research in the field of diabetes mellitus. Furthermore, limited grants are also available for the students of medical colleges for smaller projects. Recently, RSSDI has developed a simple user-friendly novel approach to decide the appropriate antidiabetic agent to be used in type 2 diabetes through the ‘therapeutic wheel’. The best choices can be determined from the outer rings of the wheel (orange and red), and the choices can be further streamlined by an ‘individualised approach’ (Fig. 6.4).