Developing an Emergency Preparedness Program

Angela Hewlett

Shelly Schwedhelm

Paul Biddinger

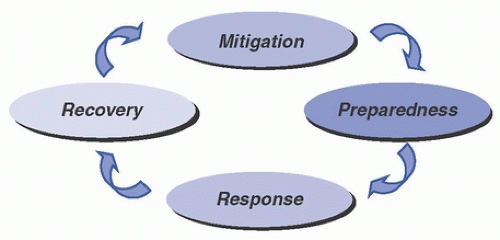

Disasters and major emergencies that disrupt healthcare operations are expected events. In the World War II era, emergency management focused primarily on preparedness for enemy attack. Since then, however, emergency management has evolved to the expanded goal of providing protection and response for all hazards (eg, pandemics, biologic threats, outbreaks, adverse weather, interruption of critical services). Modern effective emergency management utilizes a functional approach that reaches across the entire predictable life cycle of disasters and encompasses activities including establishing strategies to mitigate hazards, developing effective response plans, responding properly to events when they occur, and recovering from the disaster’s effects. Figure 48-1 illustrates the four phases of emergency management as outlined by the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).1 Emergency management programs must engage a broad range of participants in cooperative planning and must develop and refine systems that ensure appropriate use of resources and a shared responsibility among all key stakeholders. Key stakeholders in emergency management programs include representatives from hospitals and other healthcare institutions, public health, municipal emergency management, emergency medical services (EMS), and other varied agencies and constituents, including the general public. Depending on the nature of the emergency, healthcare epidemiologists and infection preventionists may serve as leaders of emergency management programs and may have active roles in all four phases of emergency management within the healthcare system.

All phases of emergency management must be considered to effectively prepare for, mitigate, respond, and recover from a biological threat or incident whether it is an outbreak, a pandemic due to a novel strain of influenza, a bioterrorism event, or emergence of a special pathogen that enters the United States. These biological scenarios are highly probable and require not only expert disaster emergency planning to ensure an effective healthcare response but also the use of strong societal business continuity strategies to minimize the numerous additional impacts to the economy, transportation, and overall limitations of movement of people and resources that can be expected.

The core phases of all-hazards emergency management are operationalized in the United States through the national framework of the National Incident Management System (NIMS), which was created as a Homeland Security Presidential Directive in 2003. This flexible framework optimizes interoperability among the entire response community, including healthcare, public safety, public health, and all other stakeholders. Healthcare facilities are required to utilize the NIMS framework in their emergency planning and response, and individuals in healthcare who support the disaster response are required to complete NIMS education modules in order to ensure effective understanding of the national framework at the local level.

MITIGATION

Mitigation, one of the core phases in the emergency management cycle, includes any activities that prevent an emergency, reduce the likelihood of occurrence, or reduce the damaging effects of unavoidable hazards. Mitigation activities should be thoughtfully considered and implemented long before an emergency occurs. Mitigation efforts in healthcare are typically identified through a structured risk assessment of hazards and other threats that may have potential impacts on the care, treatment, or services

provided to patients. The structured assessment used in healthcare is referred to as the hazard vulnerability analysis (HVA).2 The HVA considers three key variables for each kind of hazard identified: (1) the probability of the threat, (2) the consequence of the threat occurring, and (3) the existing readiness of the organization to face this threat. Numerical weights are assigned to each variable and then combined to develop an overall risk score for every hazard. These risk scores can then be used to compare very dissimilar hazards (such as floods, terrorism, and pandemics). Hospitals have a regulatory requirement to conduct and annually review and update their HVA. The risks associated with each hazard are analyzed to prioritize planning, mitigation, response, and recovery activities. The HVA serves as a needs assessment for the emergency management program. The HVA process should involve community partners, and the results should be communicated to community emergency response agencies.

provided to patients. The structured assessment used in healthcare is referred to as the hazard vulnerability analysis (HVA).2 The HVA considers three key variables for each kind of hazard identified: (1) the probability of the threat, (2) the consequence of the threat occurring, and (3) the existing readiness of the organization to face this threat. Numerical weights are assigned to each variable and then combined to develop an overall risk score for every hazard. These risk scores can then be used to compare very dissimilar hazards (such as floods, terrorism, and pandemics). Hospitals have a regulatory requirement to conduct and annually review and update their HVA. The risks associated with each hazard are analyzed to prioritize planning, mitigation, response, and recovery activities. The HVA serves as a needs assessment for the emergency management program. The HVA process should involve community partners, and the results should be communicated to community emergency response agencies.

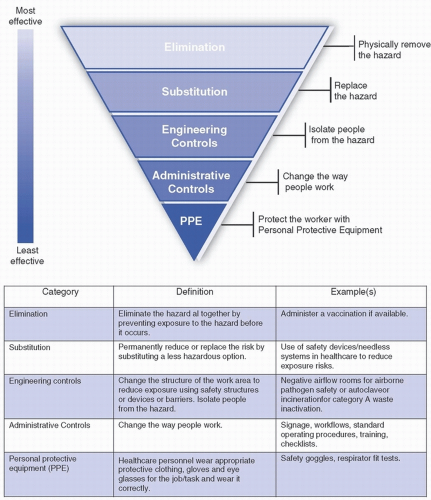

Once the HVA is completed, the hospital’s emergency management personnel and committee should identify any mitigation strategies that may be needed to reduce the hazard/risk. In biological incidents, mitigation strategies are numerous and can be implemented well in advance of an occurrence. Strategies may include development of tools and protocols designed to identify patients potentially infected with high-consequence infectious diseases (HCIDs) as early as possible upon presentation to the healthcare system, identification of appropriate initial isolation spaces for suspected HCID patients in all frontline clinical areas, and creation of standard operating procedures (SOP) or workflows that guide practice or procedures in a high-risk situation such as a biocontainment unit or busy emergency department caring for a person under investigation (PUI) for a HCID. The hierarchy of controls (Fig. 48-2), as defined by the U.S. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), is a useful tool to consider when establishing mitigation strategies for emergencies.

During the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, healthcare facilities prepared for the unknown impacts of workforce and resource limitations, including an initial lack of a vaccine. In a biological scenario such as a pandemic or any other disaster, a potential mitigation strategy includes the creation of a robust business continuity plan (BCP). A pandemic planning assumption from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is that 40% of the workforce will either be absent, ill or will not come to work.3 In the absence of an adequate workforce, there will be a clear need to identify activities that can cease, what can be delegated and what resources exist to accommodate a stressed supply chain. A pandemic plan may include surge strategies to include prioritization of care needs and triage for resource allocation, staffing strategies, supply chain strategies, medical countermeasure strategies, and varied other priority situations that will occur. A BCP is also useful for other hazards, such as those that affect infrastructure (eg, flood) or information technology (eg, cyber). All businesses, including healthcare facilities, should define how to best protect personnel and assets and how to maintain operations in the event of a disaster by having a BCP. A BCP involves:

Defining potential risks

Determining how those risks will affect operations

Implementing safeguards and procedures designed to mitigate those risks

Testing those procedures to ensure that they work

Periodic review of the process to make sure that it is up-to-date

The purpose of business continuity planning is to augment good will, as well as create internal credibility with healthcare personnel (HCP) and external customers to include the community served. Disasters are the time when communities need their local health systems the most, and mitigation plans such as BCPs are essential to the wellbeing of all communities.4

PREPAREDNESS

Planning

In an emergency department (ED), urgent care center, or primary care clinician’s office, the presentation of even a single patient who may be infected with an HCID such as Ebola or Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) can present a major challenge for many healthcare organizations. Unfortunately, many factors challenge an organization’s ability to appropriately plan to identify patients with potential HCID infections and institute proper infection control procedures. These can include a lack of familiarity with current HCID definitions and exposure risk factors, as well as a lack of knowledge regarding the actions necessary once a suspect patient is identified. In addition, evolving case definitions from public health authorities, as well as changes in clinical guidance regarding recommended actions, as can occur with a new or newly emerging pathogen, further complicate patient assessment. Inadequate early implementation of appropriate infection prevention measures can have severe consequences, and prior delays have resulted in nosocomial transmission.5,6 The identifyisolate-inform framework introduced by the CDC during the 2014-2016 Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreak can serve as a basic framework upon which further planning for the evaluation of patients suspected of infection with any highly infectious disease, not just EVD, can be used in any setting.7

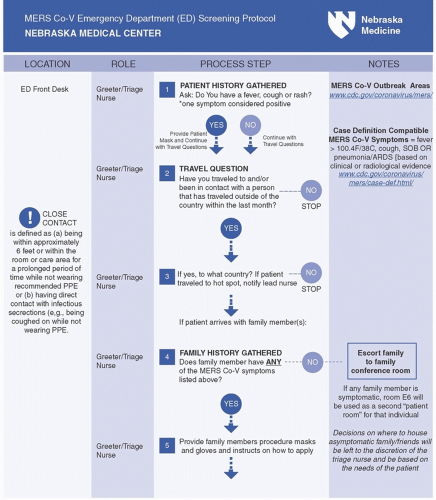

Whenever possible, hospital plans should prompt clinical triage or registration symptoms to ask arriving patients about epidemiologically important HCID risk factors such as travel history at each point of entry to the facility and

to require documentation of the answers in the medical record (Fig. 48-3). Those patients who are identified to have both clinical and epidemiological risk factors for an HCID are often called persons under investigation, or PUIs. Once a PUI is identified, emergency management plans must also provide for mechanisms to support the effective implementation of appropriate transmission-based precautions including proper use of specific personal protective equipment (PPE) and immediate isolation of the patient. Emergency management plans developed to support the evaluation of patients suspected of HCID infections must support patient safety but also must minimize the potential disruptions to routine facility operations, since the number of suspected patients will most likely outnumber actual confirmed cases, creating substantial operational and economic costs for institutions if not managed efficiently. Plans must also ensure timely notification of internal and external leadership personnel, including relevant experts and authorities, to obtain additional expert guidance, as well as to mobilize additional response resources, when required.

to require documentation of the answers in the medical record (Fig. 48-3). Those patients who are identified to have both clinical and epidemiological risk factors for an HCID are often called persons under investigation, or PUIs. Once a PUI is identified, emergency management plans must also provide for mechanisms to support the effective implementation of appropriate transmission-based precautions including proper use of specific personal protective equipment (PPE) and immediate isolation of the patient. Emergency management plans developed to support the evaluation of patients suspected of HCID infections must support patient safety but also must minimize the potential disruptions to routine facility operations, since the number of suspected patients will most likely outnumber actual confirmed cases, creating substantial operational and economic costs for institutions if not managed efficiently. Plans must also ensure timely notification of internal and external leadership personnel, including relevant experts and authorities, to obtain additional expert guidance, as well as to mobilize additional response resources, when required.

FIGURE 48-2 The hierarchy of controls. (Adapted from The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/hierarchy/default.html) |

Depending on the infectious disease suspected, the specific plans and resources needed to support the safe clinical evaluation and care of the patient can vary in complexity. In the case of EVD, the need for specialized PPE and training, well-developed procedures, and dedicated space can be extremely resource-intensive. Hospitals must carefully choose and prepare the most appropriate location for managing PUIs, ideally well in advance of being asked to care for such a patient. Some hospitals evaluate their PUIs in a section of their ED, while others use a separate, specialized, inpatient, or other isolation area. Once the PUI has arrived in his or her appropriate clinical location for evaluation, two important parallel processes must begin. The first is to ensure that the patient receives appropriate medical evaluation and care, as any patient would who is not a PUI. The second is to undertake the appropriate

diagnostic testing to establish a diagnosis. Because the PUI may have immediate medical needs, the clinical facility must be able to provide stabilizing medical care if it is needed up to the level of their care capability, potentially including airway and respiratory support, venous access, and administration of intravenous fluids, parenteral antibiotics, and vasopressor support.

diagnostic testing to establish a diagnosis. Because the PUI may have immediate medical needs, the clinical facility must be able to provide stabilizing medical care if it is needed up to the level of their care capability, potentially including airway and respiratory support, venous access, and administration of intravenous fluids, parenteral antibiotics, and vasopressor support.

In general, an airborne infection isolation (AII) room should be selected for HCID PUI investigations if possible, and a private bathroom is also desirable. In addition, the site should support both safe entry of clean clinical HCP into the room and safe exit for HCP with a clearly demarcated area for doffing of PPE. Ideally, the room or site selected will be located so as not to excessively disrupt other clinical activities. Evaluation of the PUI can be a labor- and material-intensive process, creating congestion as well as visible distractions for other patients and HCP. Therefore, it is advisable, when possible, to choose

a room to evaluate PUIs that is located away from the center of the ED to minimize interference to the other important ongoing ED activities and use physical barriers when possible to reduce disruption to routine care. Some facilities plan to keep PUIs in their ED room only until the initial assessment and first round of testing are completed, while other facilities plan to keep their PUIs in the ED room until the diagnosis has been definitively ruled in or out, which can potentially take several days (up to 3 days in the case of EVD). If a healthcare facility is not planning of providing long-term care for a PUI, then they need to have a detailed plan for safe transfer to another facility. A planning team consisting of physicians, nurses, infectious disease experts, infection preventionists, facilities managers, and laboratory leadership should convene to review these questions and begin planning their use of space for PUI evaluation.

a room to evaluate PUIs that is located away from the center of the ED to minimize interference to the other important ongoing ED activities and use physical barriers when possible to reduce disruption to routine care. Some facilities plan to keep PUIs in their ED room only until the initial assessment and first round of testing are completed, while other facilities plan to keep their PUIs in the ED room until the diagnosis has been definitively ruled in or out, which can potentially take several days (up to 3 days in the case of EVD). If a healthcare facility is not planning of providing long-term care for a PUI, then they need to have a detailed plan for safe transfer to another facility. A planning team consisting of physicians, nurses, infectious disease experts, infection preventionists, facilities managers, and laboratory leadership should convene to review these questions and begin planning their use of space for PUI evaluation.

If a patient is confirmed to have infection with an HCID, the hospital’s emergency operations plans must also anticipate how best to provide safe care throughout the patient’s hospitalization. All bedside HCP must be provided with appropriate supplies of PPE for use and must be fully trained and capable of donning and doffing PPE safely. To limit the potential spread of biological contamination outside of the patient’s room, special procedures may need to be developed to properly clean and package blood and other biological samples before they leave the room for transport to the hospital or state public health lab. Waste handling and management plans are essential, since the volume of waste (especially PPE) can be substantial, and special waste handling regulations may be relevant for certain types of diseases. Additionally, depending on the specific HCID, regular laboratory and imaging equipment may not be available (or available at the standard frequency or turnaround time) to support usual medical care, so clinical protocols and HCP training should anticipate potential alterations to usual care if needed. The range of specific resuscitative and potentially invasive medical services and procedures that will be offered to a patient who has a suspected or confirmed HCID is a highly challenging decision and is one that should be approached carefully. Depending on the disease, hospital administrative, medical, legal, and ethical leaders must consider whether they will be able to safely offer certain therapies and interventions including hemodialysis, endoscopy, or other procedures that may present elevated risks to HCP and the facility. These decisions should be made prospectively as part of the hospital planning and preparedness program. If a specific necessary procedure is not available at the hospital caring for a patient with an HCID, public health officials may assist in determining if it may be available elsewhere, such as at one of the ten regional Ebola and other special pathogen centers (RESPTCs) in the United States.8

Planning for large, pandemic outbreaks of infectious disease requires substantial additional and different kinds of effort for hospital emergency managers and their public health and municipal emergency management colleagues. With pandemic planning, hospitals must anticipate substantially increased volumes of patient visits to primary care, urgent care, and emergency department sites and may need to develop specialized sites for outpatient clinical evaluations. Hospitals will also likely be asked by public health and other governmental authorities to “surge” their inpatient care capabilities, even potentially exceeding their licensed bed capacity. The surge planning requires careful anticipation of how to maximize the use of their available spaces, HCP, supplies, and devices (eg, ventilators). The CDC has developed a useful checklist of actions for hospitals to guide their pandemic planning efforts.9

Building Emergency Response Teams

In general, there are two different kinds of emergency response teams that are required for effective response to infectious disease emergencies and disasters. The first type of team provides the necessary bedside clinical care and support needed for the care of the patient, while the other team provides the leadership necessary for coordination of care activities and logistics.

Hospitals in the United States use varying types of clinical teams in order to provide safe and effective care to PUIs and confirmed cases of HCIDs. Some hospitals use teams of volunteers, while others mandate participation depending on the clinicians’ unit assignments. Certain hospitals limit participation to a subset of clinical practice areas, such as EDs, intensive care units (ICUs), and operating rooms (ORs), while others accept team members from the entire organization. No matter what structure is chosen, there are several common elements that must be considered for all HCID response teams. First, hospitals must be able to mobilize appropriately trained staff for the evaluation and care of a PUI or confirmed case of an HCID 24 hours/day. All HCP participating in care activities must know how to select the appropriate PPE for the disease(s) suspected. More importantly, HCP must also be trained in how to safely don and doff the PPE. For PPE ensembles that are substantially different than those normally worn in common clinical activities, such as the PPE required for the care of a patient suspected or confirmed to have EVD infection, the CDC recommends that HCP receive frequent refresher and practice opportunities in donning and doffing of PPE.10 HCP should also receive training and opportunities to practice procedures in specimen collection and packaging, waste handling, and patient transport consistent with the protocols specified by their institutional plans.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree