General Introduction

Whenever calcifications areseen on the mammogram, the radiologist should attempt to determine the anatomical cavity within which the calcifications have been formed. The options are the following:

- Within the ducts (secretory disease type and casting type calcifications)

- Within the TDLUs (crushed stone-likeand powdery calcifications)

- Outside the glandular tissue (calcifications within the walls of blood vessels, within the stroma, around oil cysts, or in the skin are characteristically benign)

Knowledge of the cradle in whichthe calcifications have been formed as well as analysis of their shape, density, and distribution will facilitate an understanding of the underlying pathophysiological process.

This volume deals with the most unpredictable entity among the breast cancer subtypes, which appears on the mammogram as casting type (BI-RADS® fine, linear, branching) calcifications.1–6 Adetailed description of all of the following aspects is provided to assist the reader in understanding this complex breast cancer subtype:

1 Mammographic features

2 Mammographic–histological correlation using subgross (three-dimensional; 3D) large-section histology

3 Differential diagnosis

4 Clinical presentation

5 Natural history: tendency for recurrence, therapeutic failures, long-term outcome

6 A novel theory explaining the unexpectedly poor outcome of some cases with casting type calcifications

7 Practical implications for the management of patients with casting type calcifications

A unique collection of 3D mammographic/subgross 3D pathology images for stereoscopic viewing with companion 2D conventional histology images is included at the end of this volume.

Description of Calcifications localized within the Ducts

Anatomical Background

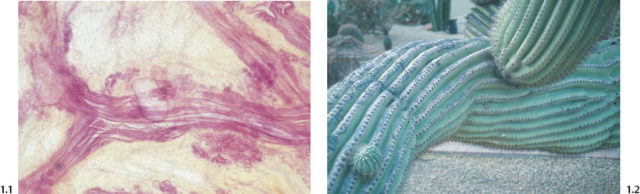

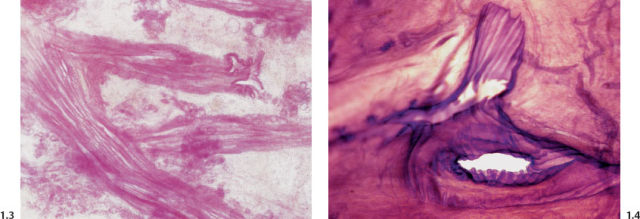

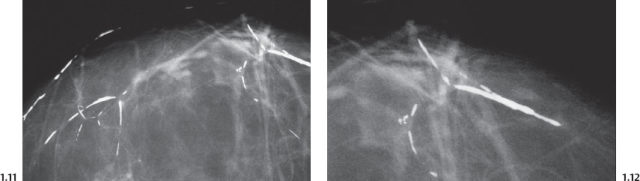

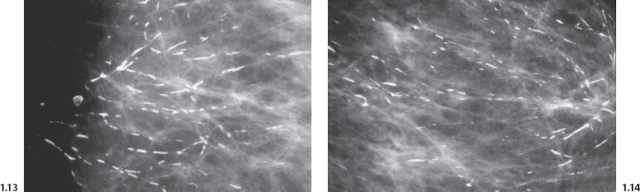

The milk duct in the resting state is pleated and measures about 0.1–0.5 mm in width (Figs. 1.1 to 1.4).

Accumulation of either fluid or cancer cells with necrotic debris will greatly distend the duct system.1 Differentiating these two entities from each other is a challenge faced by the radiologist.

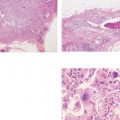

Fig. 1.1 Subgross histological image of milk ducts in the resting state.

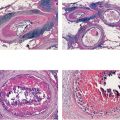

Figs. 1.3 & 1.4 Subgross histological images of milk ducts, longitudinal and cross sections.

“Secretory Disease” Type, Plasma Cell Mastitis Type Calcifications

An excessive amount of fluid produced by the TDLUs can gradually accumulate within the ducts and their branches.

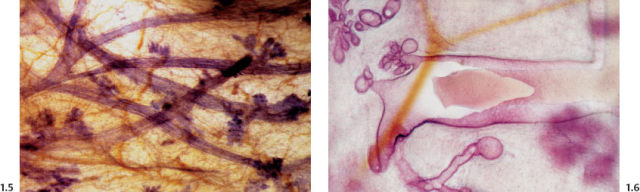

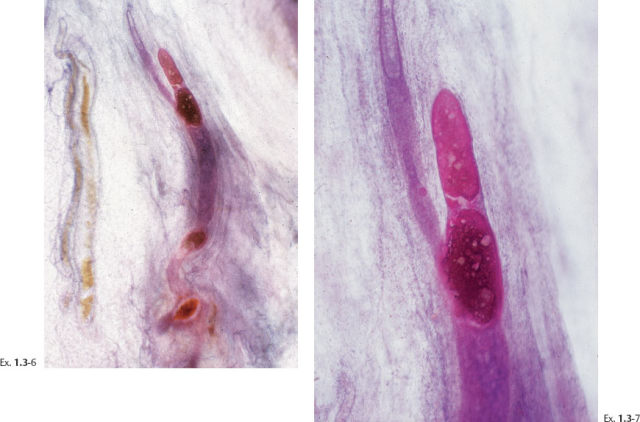

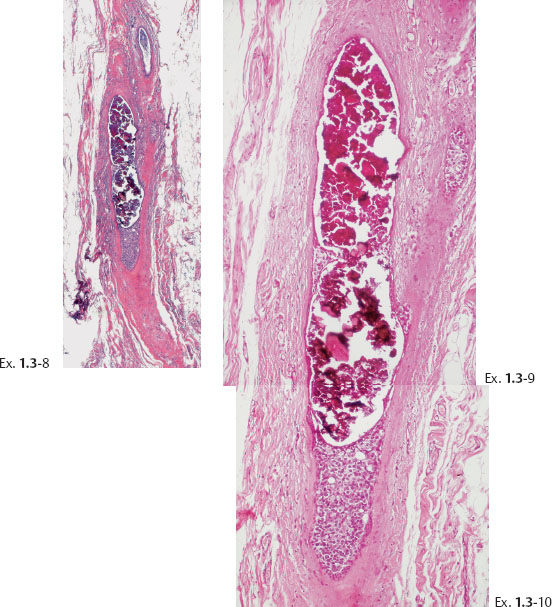

Figs. 1.7 & 1.8 Subgross histological images of milk ducts distended by inspissated fluid.

Figs. 1.9 & 1.10 Subgross histological images of milk ducts distended by inspissated fluid.

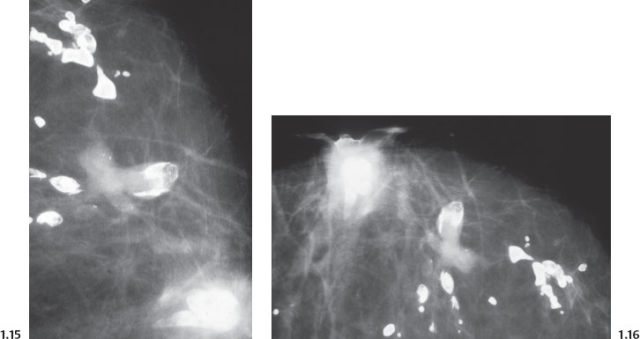

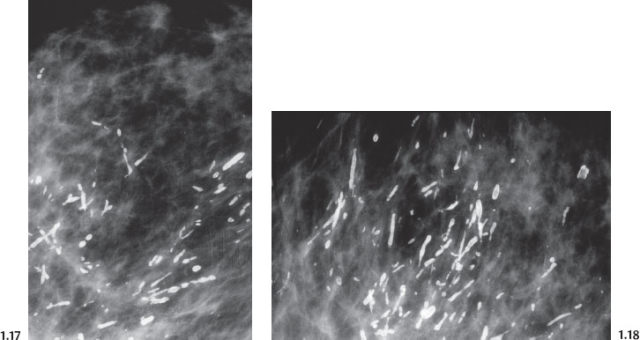

As water is resorbed from this fluid, the residual alkaline, proteinaceous material may calcify. These linear, often branching calcifications are localized within the preexisting duct system and reflect its regular, harmonious structure. This process, commonly called “secretory disease,” is bilateral, which explains the usual bilateral presentation of these typical calcifications.

There are two mammographic presentations of these calcifications:

1 Long, needle-like calcifications (intraductal form)

2 Hollow, ringlike or tubelike calcifications (periductal form)

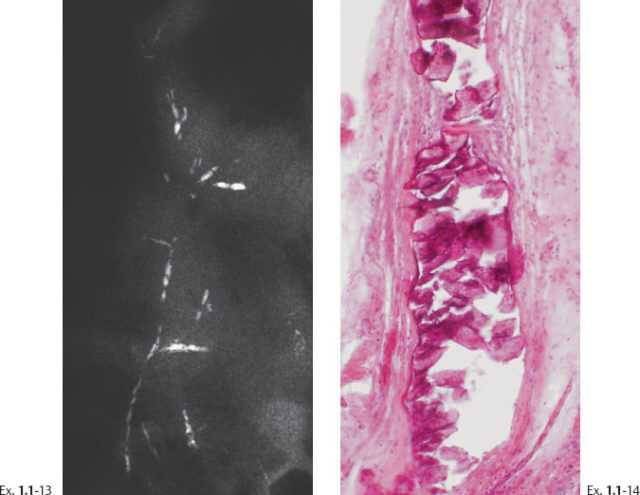

Intraductal form: The more commonly occurring long, needle-like calcifications are merely calcified duct contents, which assume the smooth, regular outline of the duct lumen. The mammographic image of these calcifications will also have a homogeneously high density (Figs. 1.11 to 1.18).

Casting Type Calcifications

Fragmented and Dotted Casting Type Calcifications

Fragmented and Dotted Casting Type Calcifications

It is important to differentiate the plasma cell mastitis/secretory disease type calcifications from the calcifications seen in a breast cancer subtype commonly called high nuclear grade/poorly differentiated/Van Nuys Group 3/Grade 3 DCIS.

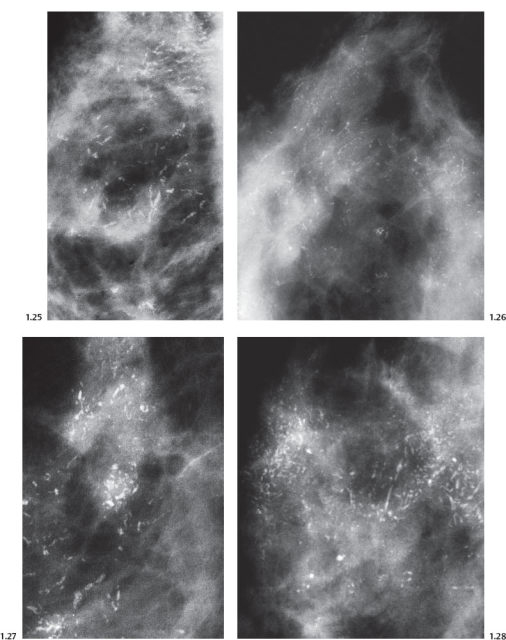

The striking differences are the unilateral, lobar distribution and the highly irregular, disharmonious appearance of the malignant type calcifications. There are two mammographic presentations: the fragmented casting type and the dotted casting type, determined by the cellular growth pattern of these two high-grade malignant processes.

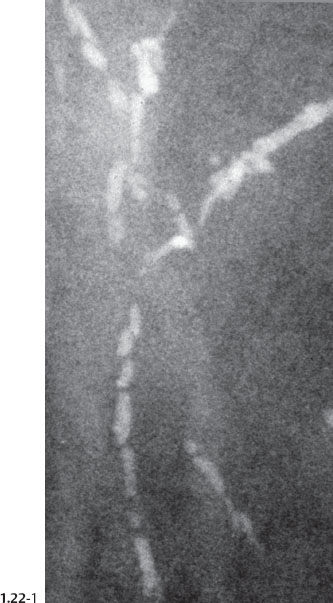

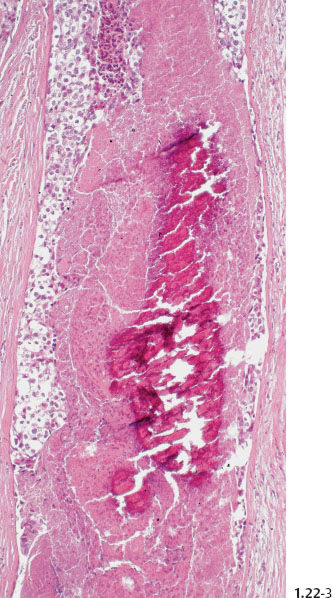

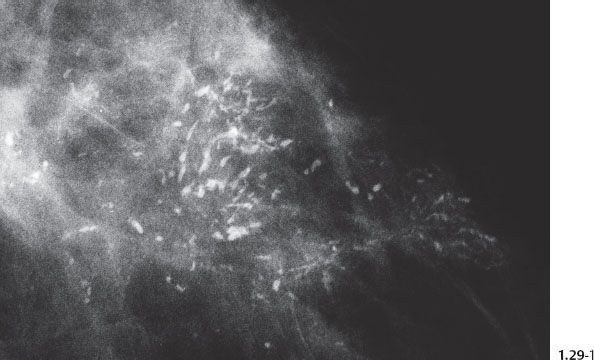

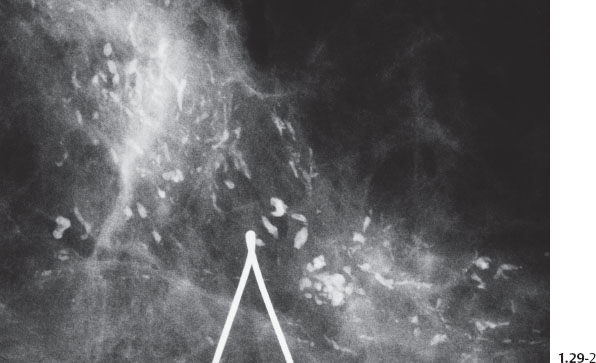

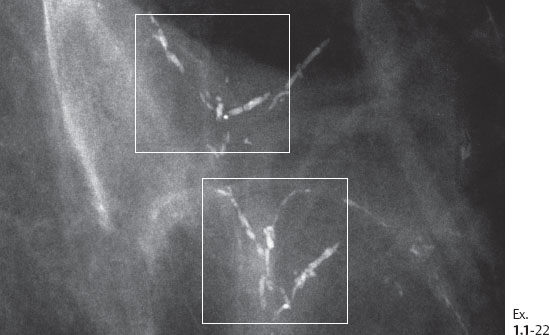

The solid growth pattern of high nuclear grade, poorly differentiated cancer cells produces extensive intraluminal necrosis and amorphous calcifications, which correspond to the mammographic image of fragmented, elongated and branching calcifications (Fig. 1.22-1 to 3). The ductal lumen is filled with cancer cells, necrotic debris, and amorphous calcifications that outline segments of the distended duct lumen in the form of solid, intermittent, cylindrical casts. These fragmented casting type calcifications form a partial outline of the duct and its branches on the mammogram (Figs. 1.25 to 1.29). The origin of these calcifications can be deduced from their typical mammographic appearance. Initially these calcifications will have an irregular contour but, as the necrotic process advances and the debris becomes more extensively calcified at the expense of the viable malignant cells, the mammographic image will exhibit calcifications with a smoother outline and a more homogeneous density. This may occasionally cause differential diagnostic problems if the analysis is restricted to individual calcifications. However, the localized, lobar distribution of these calcifications and their remarkable heterogeneity should resolve this deceptive appearance. (Examples 1.3 to 1.5). Microfocus magnification images will provide additional help in differential diagnosis because considerably more calcifications will become evident if the lesion is malignant, whereas magnification will not reveal additional plasma cell mastitis type calcifications. Rarely, a partially calcified fibroadenoma, traumatic fat necrosis, or benign intraductal papilloma may contain focal branching calcifications, which mimic casting type calcifications.

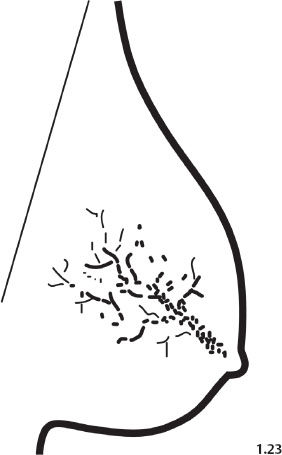

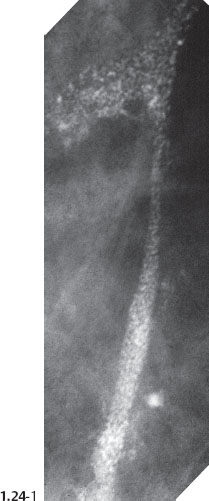

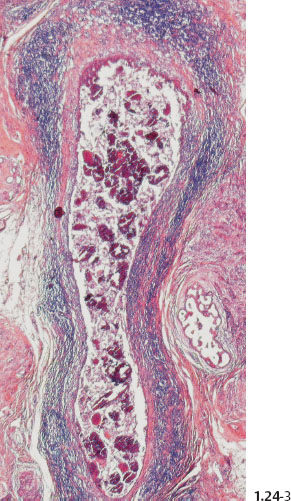

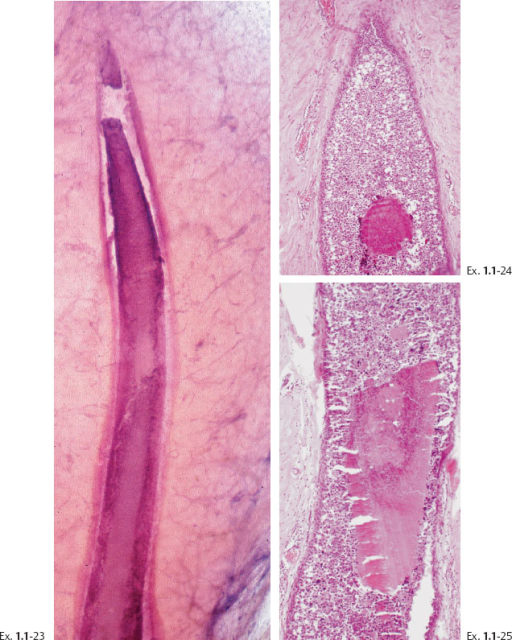

When the dominant histological featureisthe micropapillary growth pattern, the dotted casting type calcifications are seen on the mammogram. In this type the duct lumen is filled with innumerable, separate, tiny, amorphous calcified particles. The tips of the micropapillary tumor growth extensions break off and eventually calcify. These individual calcified particles accumulate to form the typical dotted casting image on the mammogram. (Fig. 1.24-1 to 3). There is no benign pathological process localized within the ducts that produces a similar mammographic image.

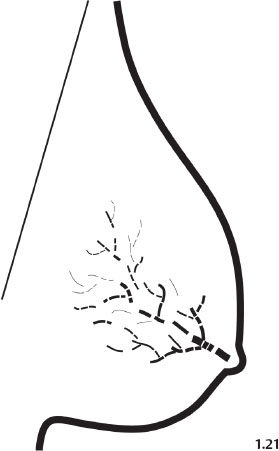

An overview of the histological–mammographic correlation of these two subtypes of high-grade DCIS, seen on the mammogram as fragmented and dotted casting type calcifications, is presented in Figs. 1.21 to 1.24.

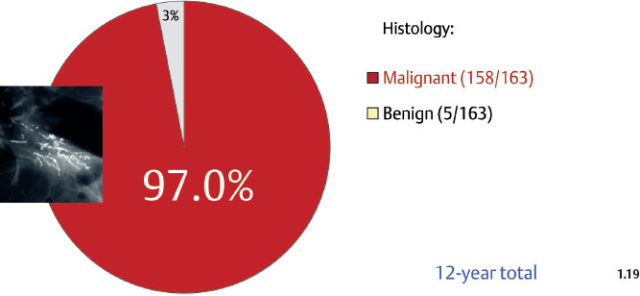

Although relatively infrequent, the casting type calcifications represent the most reliable mammographic sign of malignancy, as 97% of them will be malignant at histology (Fig. 1.19). The remaining 3% are found in fibroadenomas, benign papillomas, and rarely in traumatic fat necrosis.

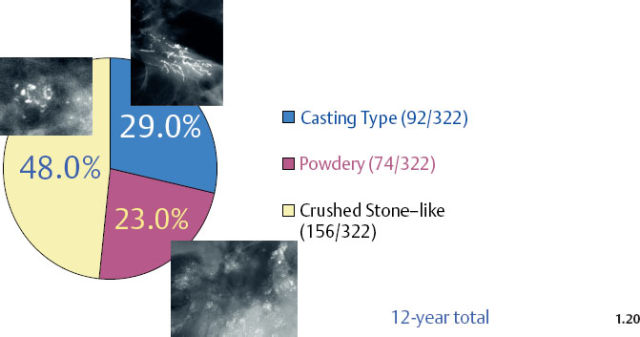

The distribution of malignant type calcifications is shown in Fig. 1.20, based on 322 consecutive, histologically proven breast cancer cases with calcifications on the mammogram as the only radiological abnormality. Casting type calcifications accounted for about 29% of all malignant type calcifications.

Fig. 1.19 The probability of malignancy is as high as 97% when the finding on the mammogram is casting type calcification(s) with or without an associated tumor mass. Women of all ages; prospectively collected consecutive cases. These and subsequent patient material are all from the Department of Mammography, Falun Central Hospital.

Fragmented Casting Type Calcifications on the Mammogram

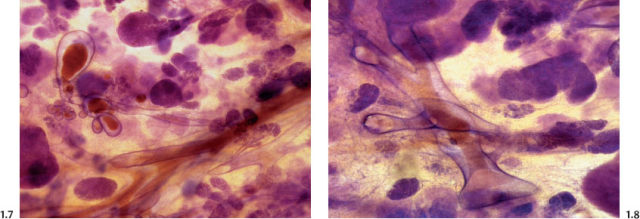

Characteristic histological features:

- Large, polymorphic nuclei with frequent mitoses

- Cell architecture: solid growth pattern

- Extensive intraluminal necrosis

- Amorphous calcifications filling segments of the ductal lumen

Characteristic mammographic image:

- Intermittent, elongated, branching, fragmented casting type calcifications

- The calcifications are usually scattered within alarge part of the lobe, where they are confined to the duct system.

Fig. 1.21 Schematic diagram representing fragmented casting type calcifications.

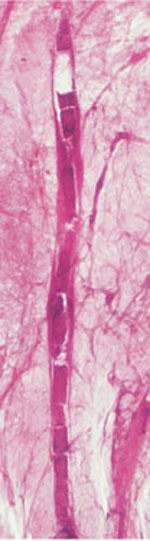

Fig. 1.22-2 Subgross, thick section (3D) histology.

Fig. 1.22-3 Conventional histology.

Dotted Casting Type Calcifications on the Mammogram

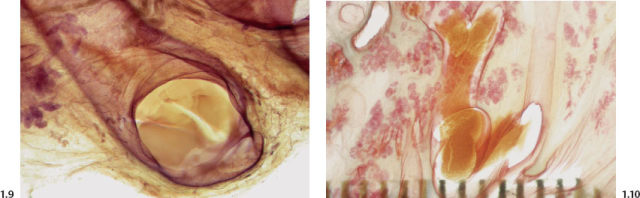

Characteristic histological features:

- Large, polymorphic nuclei

- Cell architecture: predominantly micropapillary, mixed with solid growth pattern

- Intraluminal necrosis

- Numerous discrete amorphous calcifications within the intraluminal necrosis

Characteristic mammographic image:

- Dotted casting type, “snake skin“-like

- Scattered, outlining most of the lobe

Fig. 1.23 Schematic diagram representing dotted casting type calcifications.

Fig. 1.24-2 Subgross, thick section (3D) histology

Fig. 1.24-3 Conventional histology.

Fragmented Casting Type Calcifications

Fragmented Casting Type Calcifications

Mammographic Display of Widespread Fragmented Casting Type Calcifications in Five Separate Cases

Fig. 1.29-1 Left breast, detail of the CC projection with numerous casting type calcifications without an associated tumor mass.

Fig. 1.29-2 Operative specimen radiograph of the case shown in Fig. 1.29-1.

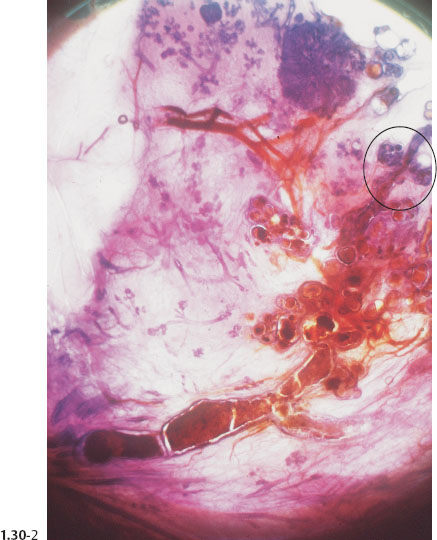

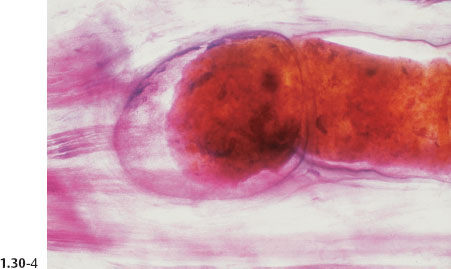

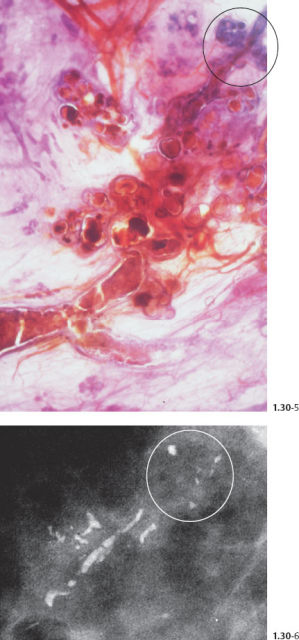

Macroscopic and Subgross Histological Correlation When Fragmented Casting Type Calcifications Fill an Entire Lobe

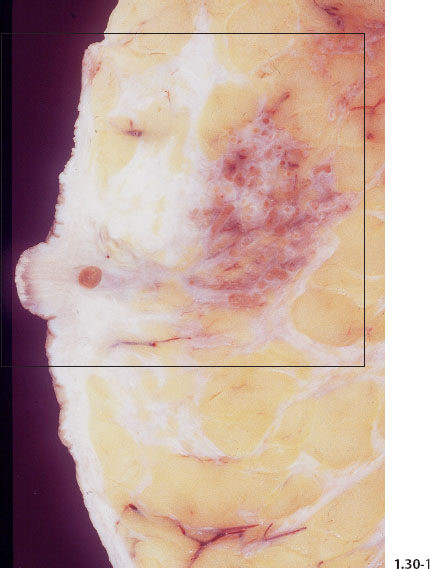

Fig. 1.30-1 Photograph of an operative specimen sliced at the level of the nipple.

Fig. 1.30-3 Further magnification of the distended TDLUs and their associated subsegmental duct.

Comment

The term “comedo carcinoma” has frequently been used to describe the subtype of DCIS with extensive necrosis, solid cell proliferation, and amorphous calcium. The duct contents are under pressure and tend to ooze out from a freshly cut surface in a manner resembling “comedones” or “comedos” when squeezed out from the skin of the face. These in turn are named from their resemblance to maggots (grub or larvae of flies and other insects), which are also termed “comedones” in Latin. This term, when applied to describe breast cancer, has the disadvantage of being variously interpreted by different subspecialists. Its use tends to lead to confusion, since it fails to accurately describe the underlying pathology.

The imprecise term “comedo” should be replaced by a detailed description of:

- The histological grade of the malignant cells

- Their growth pattern

- The presence of central necrosis and calcifications

Characteristic Mammographic and Histological Presentation of Fragmented Casting Type Calcifications on the Mammogram

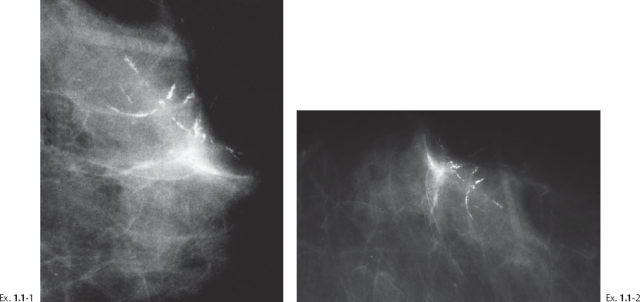

Example 1.1

A 66-year-old asymptomatic woman, screening examination.

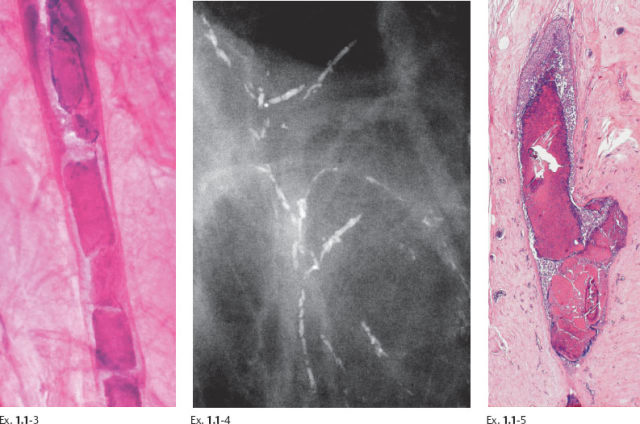

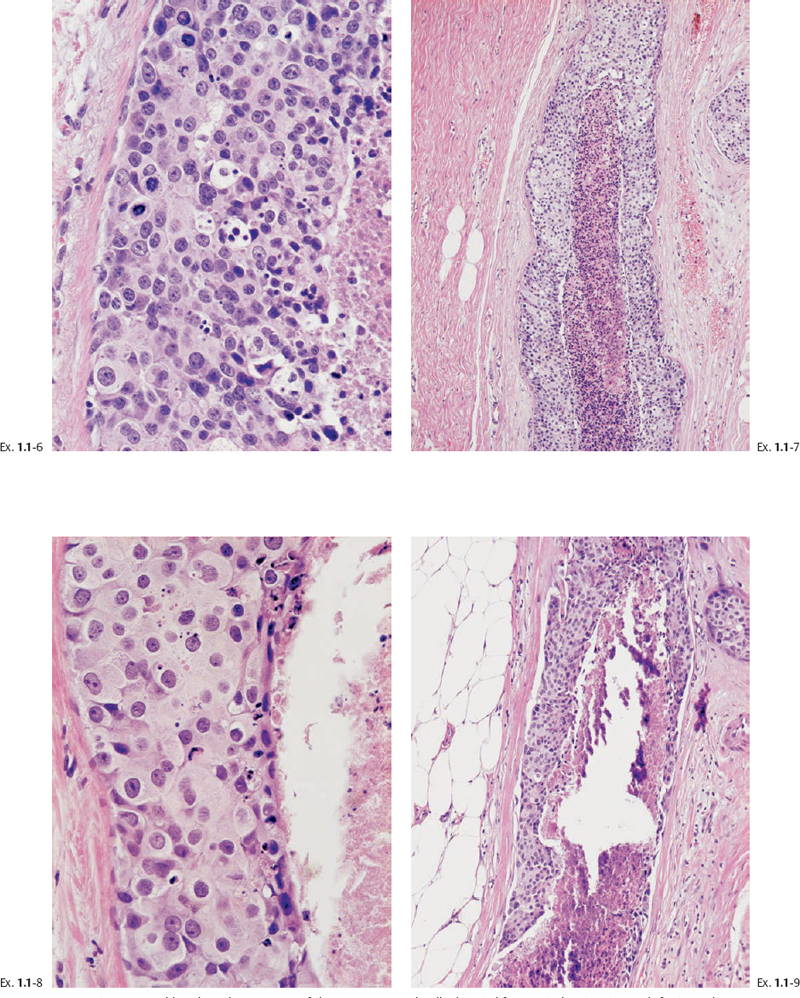

Ex. 1.1-6 to 9 Typical histological appearance of these mammographically detected fragmented casting type calcifications showing large, polymorphic nuclei with frequent mitoses, solid cell proliferation, extensive intraluminal necrosis, and amorphous calcifications.

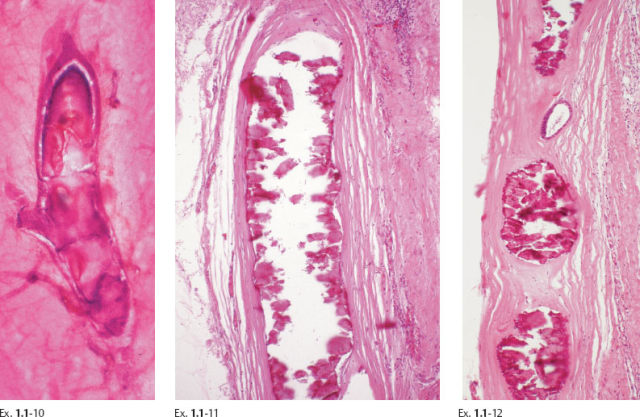

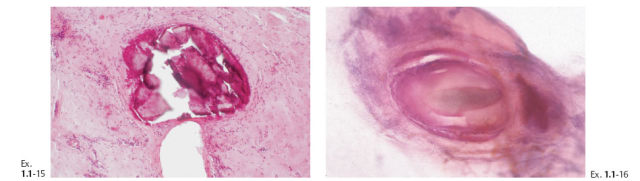

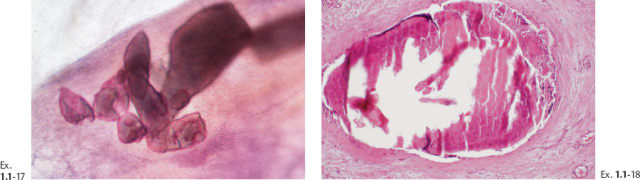

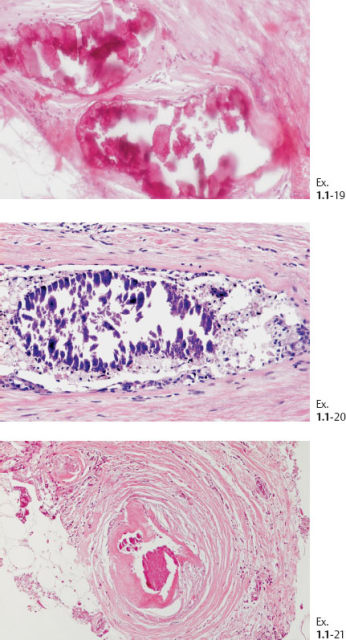

Ex. 1.1-10 to 12 Histological examination of cases with extensive fragmented casting type calcifications often reveals ducts where the necrosis encompasses the entire duct lumen, with few or no viable cancer cells remaining. These calcifications are of uniformly high density on the mammogram.

The presence of fragmented casting type calcifications is a highly reliable radiological sign of malignancy. Preoperative microscopic diagnosis is necessary for optimum patient management. Histological-mammographic correlation helps us understand that the regions containing calcifications with high, even density and smooth contour will have the fewest viable malignant cells. These are typically found in the more central portion of the region with calcifications (Ex. 1.1-19). Aiming at these regions with the larger-bore needle will harvest calcifications, but few, if any, cancer cells.

The largest number of viable cancer cells is usually found at the periphery of the region with calcifications. Targeting this area is more likely to provide diagnostic samples.

Ex. 1.1-26 The preferred site for largerbore needle biopsy is outlined by the rectangle.

Treatment and follow-up: In this case the Grade 3 DCIS was spread over an area measuring 5 cm × 3 cm. Because of close margins, mastectomy was performed. No evidence of recurrence was found at the most recent follow-up 11 years after surgery

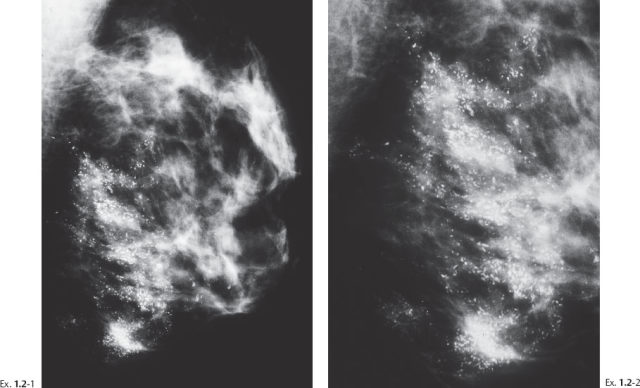

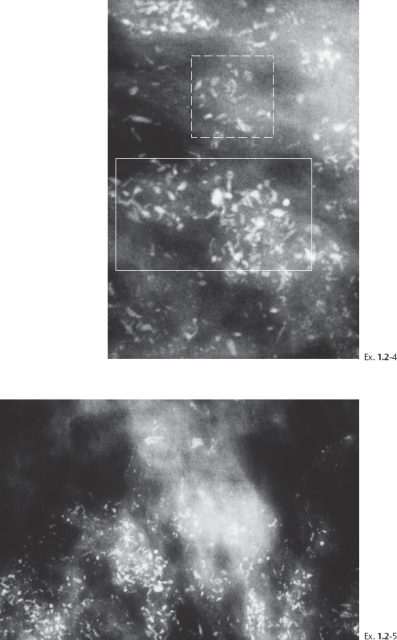

Mammographic–Histological Correlation When Both Fragmented Casting Type and Dotted Casting Type Calcifications Are Present

Example 1.2

Twenty-one months following chemotherapy for carcinoma of the cervix, this 29-year-old woman felt a “thickening” in her left breast.

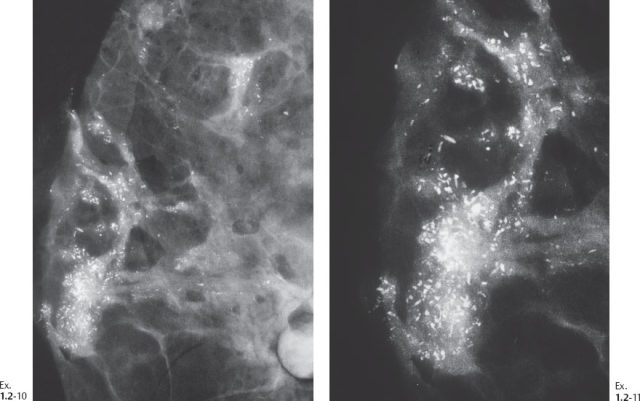

Ex. 1.2-3 Left breast, detail of the CC projection.

Ex. 1.2-4 & 5 Microfocus magnification mammography, MLO and CC projections, demonstrating both types of casting calcifications, with a predominance of the fragmented casting type. The rectangle with the dashed border outlines the dotted casting type calcifications, and the rectangle with the solid border outlines some of the fragmented casting type calcifications.

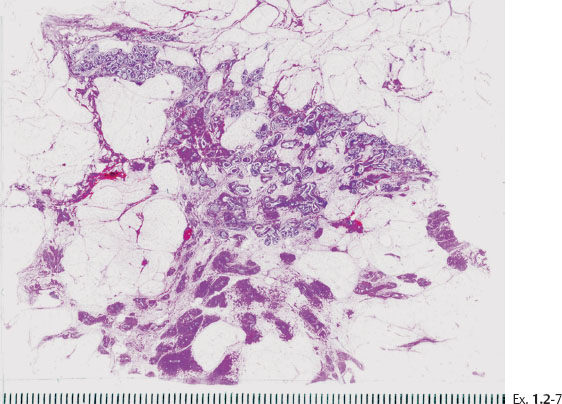

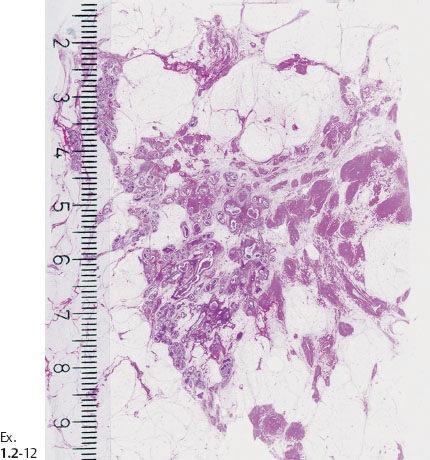

Ex. 1.2-6 Mastectomy specimen radiograph.

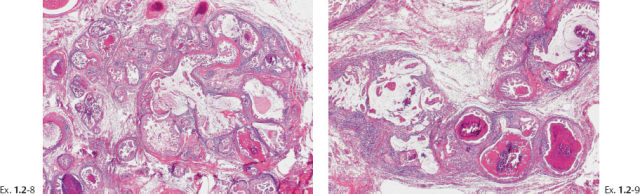

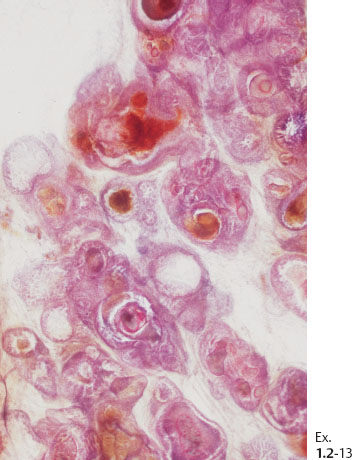

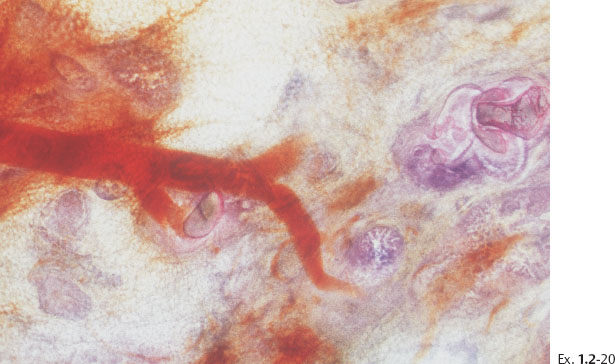

Ex. 1.2-13 Subgross histological image showing the unnaturally high density of the cancerous ducts.

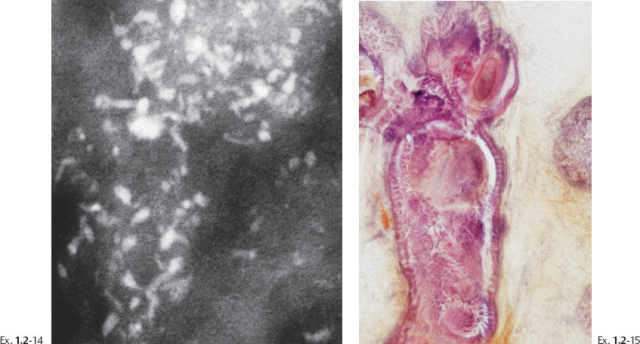

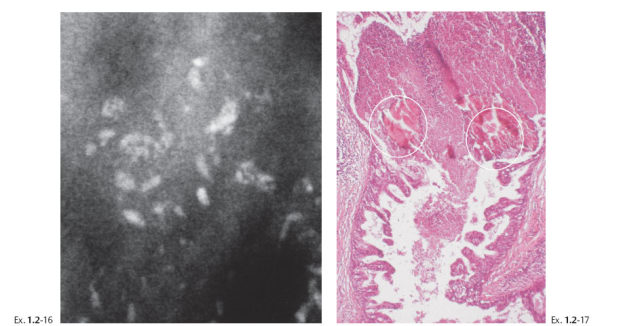

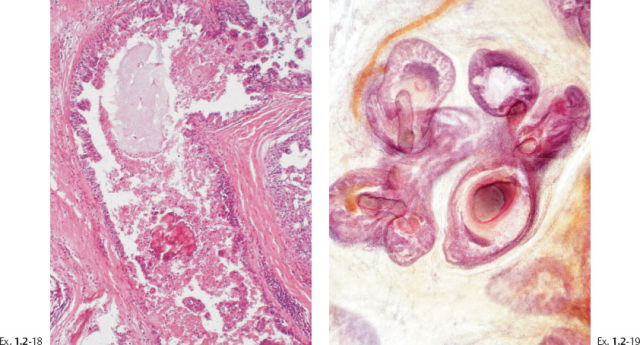

Ex. 1.2-14 & 15 Mammographic–histological correlation of a region with fragmented casting type calcifications.

Treatment and follow-up: Mastectomy. Prophylactic mastectomy of the contralateral breast revealed LCIS. Follow-up: no recurrences found nine years after operation.

Casting Type Calcifications—Differential Diagnostic Problems

Fragmented Casting Type Calcifications Which Bear a Resemblance to Benign Secretory Disease Type Calcifications

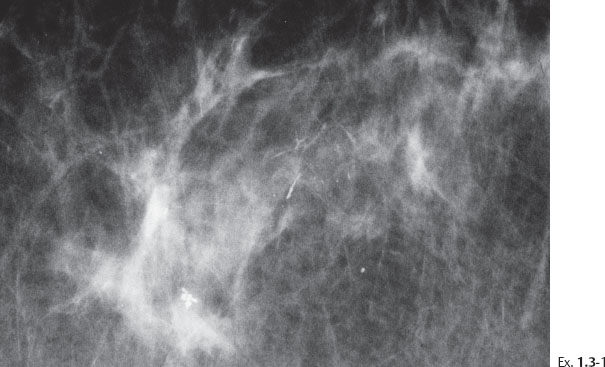

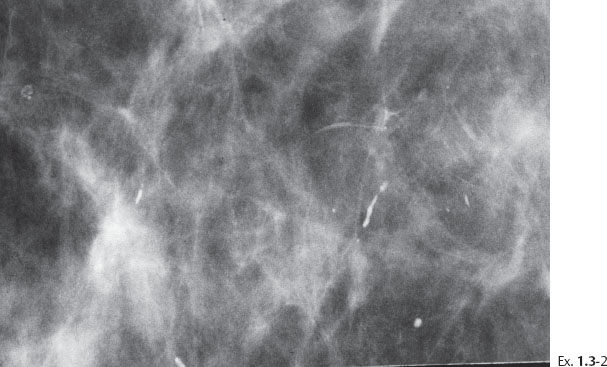

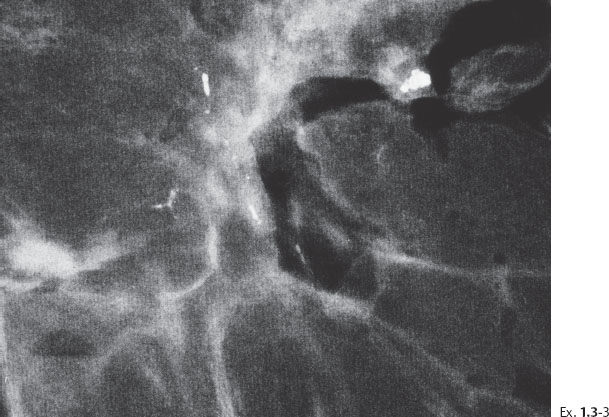

Example 1.3

A 69-year-old asymptomatic woman, screening examination.

Ex. 1.3-3 Sliced specimen radiograph.

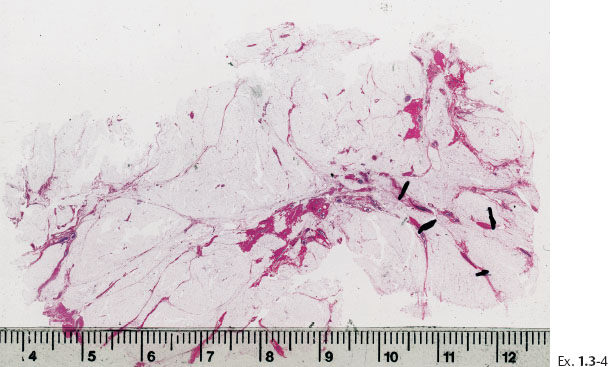

Ex. 1.3-4 Large section histology: Grade 3 DCIS found over an area measuring 2.0 cm.

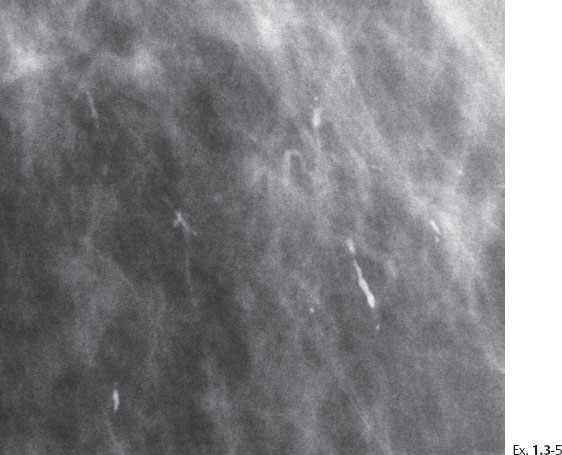

Ex. 1.3-5 Microfocus magnification in the MLO projection demonstrates that the linear calcifications have an irregular orientation, strengthening the suspicion of a malignant process within the ducts.

Differential Diagnostic Problems

Histological diagnosis: 20 mm × 20 mm Grade 3 DCIS, solid, cribriform and clinging type. No metastases were found in five axillary lymph nodes.

Treatment and follow-up: Sector resection with no additional treatment. No recurrences at the most recent followup at 10 years.

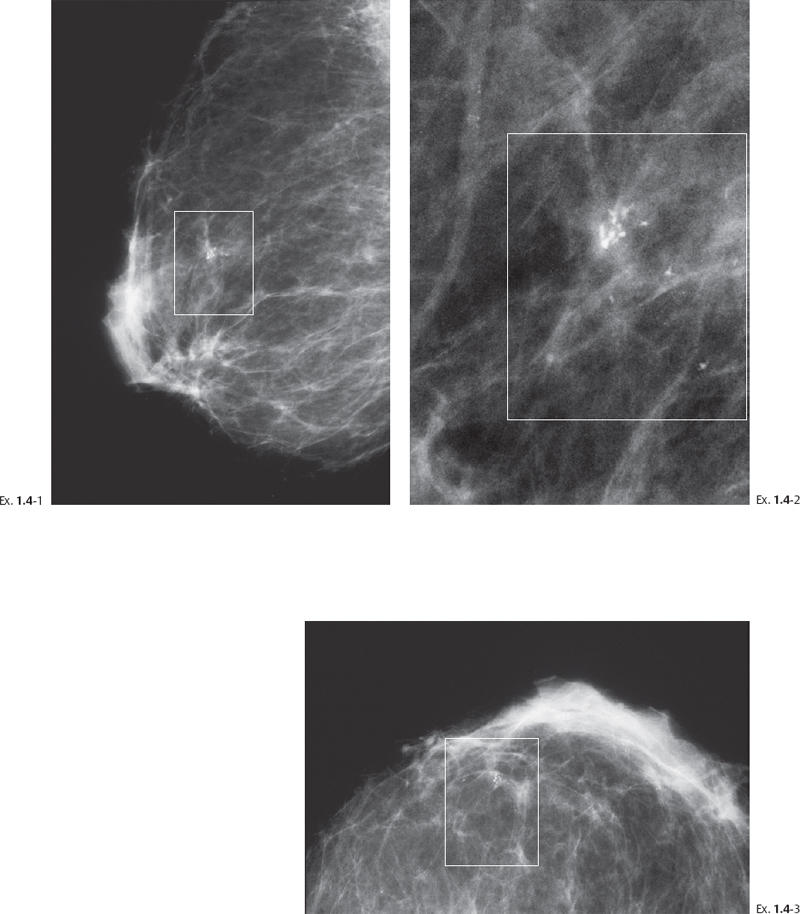

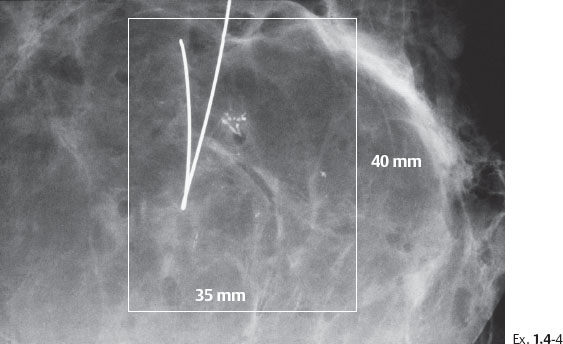

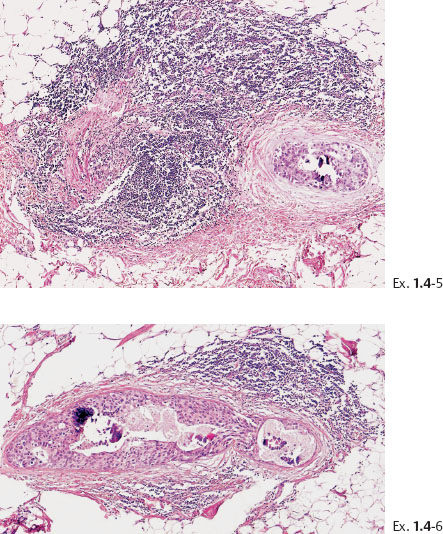

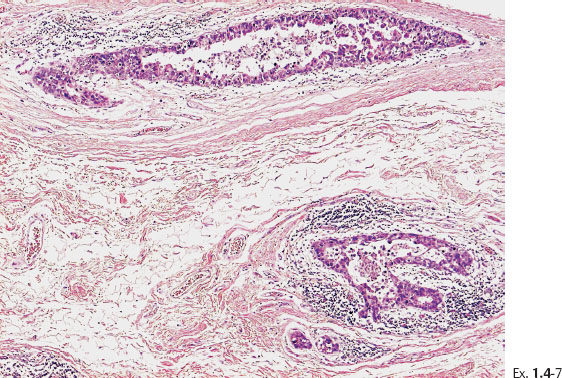

Example 1.4

A 66-year-old asymptomatic woman, screening examination.

Differential Diagnostic Problems

Ex. 1.4-7 Histology: Images of the Grade 3 micropapillary “carcinoma in situ” component with periductal desmoplastic reaction and lymphocytic infiltration.

Treatment and follow-up: Sector resection with no additional treatment. No recurrences at 16 years of follow-up.

Comment

When the fragmented casting type calcifications are localized to a small area, are smooth contoured and have a high and uniform density, it is more difficult to differentiate them from secretory disease type calcifications. The differential diagnosis is assisted by remembering the following:

1 The casting type calcifications occur unilaterally while secretory disease type calcifications are typically bilateral.

2 Furthermore, microfocus magnification mammography will always reveal additional malignant type calcifications, while the number of benign type calcifications will not be increased following magnification. This is because the malignant type calcifications are in various phases of development, so that the increased resolution of microfocus magnification will reveal the fainter calcifications that are more highly fragmented, have a more irregular contour, and are more typically malignant. On the other hand, since the benign calcifications are of uniformly high density, they will usually be already sufficiently visible on the standard mammograms.