Condition

Presentation

Differential diagnosis

Tinea pedis

Interdigital: scaling, fissuring, maceration, erosions, hyperhidrosis, pruritus, odor

Candidiasis, erythrasma, bacterial infection, psoriasis, contact dermatitis, dyshidrotic eczema, Reiter’s syndrome

Moccasin: fine silvery scales with underlying pink or red skin on soles, heels, sides of feet

Vesicobullous: inflammatory vesicular or bullous lesions, particularly at instep

Tinea manuum

Dry, scaly, hyperkeratotic skin particularly of the palmar area, minimal erythema

Contact dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, pompholyx, psoriasis lamellar

Tinea corporis

Annular erythematous plaques with raised leading edges and scaling, over glabrous skin of trunk; may be central clearing

Impetigo, nummular dermatitis, secondary or tertiary syphilis, psoriasis, lichen planus, seborrheic dermatitis, pityriasis rosea, pityriasis rubra pilaris, candida intertrigo, atopic dermatitis, cutaneous lupus, pityriasis versicolor

Tinea cruris

Annular erythematous plaques with raised leading edges and scaling, over pubic area, perineal, and perianal skin, typically not affecting the scrotum or labia majora

Psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, candidiasis, erythrasma, lichen simplex chronicus, Darier’s disease, pemphigus vegetans

Tinea capitis

Noninflammatory: erythematous papules around hair shaft spreading out with fine scaling in noticeable patches and partial or complete alopecia

Seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, tinea amiantacea, alopecia areata, trichotillomania, lupus erythematosus, lichen planopilaris, traction folliculitis, bacterial pyoderma

Black dot: noticeable black dots where hair breakage at scalp level occurs, scaling with little inflammation (particularly with T. tonsurans or T. violaceum)

Inflammatory: kerion with pustules, loose hair, discharge of pus

Favic: large yellow crusts on the scalp

Onychomycosis

Distal lateral subungual (DLSO): infection at the distal end of nail plate; discoloration and thickening of nail plate, onycholysis, subungual debris

Psoriasis, chronic onycholysis, chronic paronychia, trachyonychia, hemorrhage, onychogryphosis, lichen planus, alopecia areata, subungual malignant melanoma, subungual squamous cell carcinoma

Superficial white (SWO): white spots or patches on the surface of the nail plate

Proximal subungual (PSO): infection of the proximal nail fold, and extending distally, typically whitish in color

Endonyx: milky white discoloration of the nail plate without hyperkeratosis, onycholysis; may show lamellar splitting of the nail plate (typically caused by T. soudanense or T. violaceum)

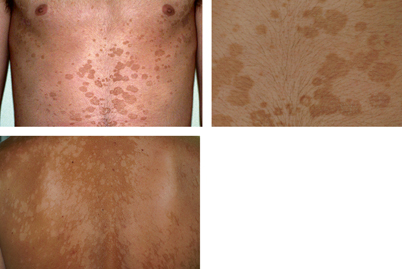

Pityriasis versicolor

Well-defined, hyperpigmented, or hypopigmented lesions of areas with high concentrations of sebaceous glands such as scalp, chest, back, upper arms, and face; showing fine scaling in most cases (caused by Malassezia species)

Vitiligo, chloasma, tinea corporis, pityriasis rotunda, erythrasma

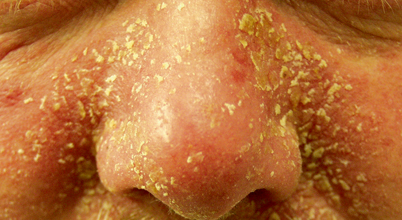

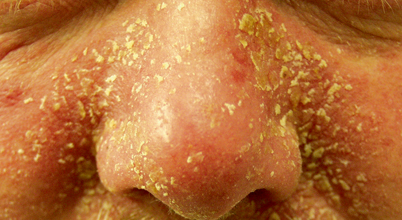

Seborrheic dermatitis

Red, flaky, greasy-looking patches of skin on scalp, nasolabial folds, eyebrows, and ears: “dandruff”; may also affect groin, axillae, anterior chest; pruritus, irritation may be associated with Malassezia infection

Psoriasis, contact dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, tinea capitis, rosacea, lupus erythematosus

Tinea Pedis/Manuum

Tinea pedis, also known as “athlete’s foot,” has three common presentations: interdigital, moccasin, and vesicobullous [9].

Interdigital is the most common and typically infects the toe webs, particularly between the fourth and fifth toes (Fig. 21.1) [9]. Interdigital infection may show fissuring, scaling, maceration, and erosion. Hyperhidrosis, pruritus, and foul odor may also be present. Dermatophytosis simplex is an uncomplicated form of interdigital tinea pedis. In contrast, dermatophytosis complex is associated with concomitant bacterial infection that can be facilitated by breakdown of the skin in preliminary infection. This form of tinea is characterized by inflammation, maceration, and odor [9].

Fig. 21.1

Interdigital tinea pedis

Moccasin tinea pedis presents as fine silvery scales with underlying pink to red skin on the soles, heels, and sides of feet (Fig. 21.2) [9]. More severe cases may show cracked, inflamed skin, erythema, and odor; this type of infection is commonly produced by T. rubrum.

Fig. 21.2

Moccasin tinea pedis, with close-up of fine scaling

Vesicobullous tinea is the least common form of tinea pedis and appears as acute inflammatory vesicular or bullous lesions, typically at the instep; however, inflammation may spread over the sole [9]. This dermatophytosis is associated with T. mentagrophytes infection.

Tinea manuum is an uncommon clinical presentation that affects the palms of the hands as a chronic dermatosis with minimal erythema and dry, scaly, hyperkeratotic skin [9]. Infections are frequently caused by T. rubrum. Tinea manuum can be associated with tinea pedis or onychomycosis, and a two-feet–one-hand syndrome [21]. The latter consists of tinea manuum with excoriation of infected tinea pedis, and/or toenail onychomycosis.

Tinea Corporis/Cruris

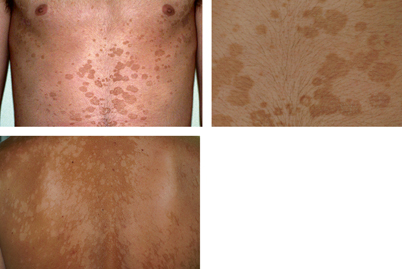

Tinea corporis is a superficial dermatophyte infection of the glabrous skin, excluding the scalp, beard, face, hands, feet, and groin (Fig. 21.3), which is more common in men and children [10]. Tinea faciei is a subset of tinea corporis that affects only the face, excluding the beard region [11].

Fig. 21.3

Tinea corporis

Tinea cruris, also known as “jock itch,” is a dermatophyte infection of the genitalia, pubic area, perineal skin, and perianal skin (Fig. 21.4). The scrotum and labia majora are typically not affected. This form of infection is more common in men [10].

Fig. 21.4

Tinea cruris

Tinea cruris and tinea corporis present as annular erythematous plaques with raised leading edges and scaling. Central clearing of the lesion may be noticed, but nodules may remain present throughout the lesion [10]. Infection is typically associated with pruritus and an erythematous papule or series of vesicles can also be present. Significant inflammation may result from infection with zoophilic organisms such as Trichophyton verrucosum, which produces large pustular lesions, a kerion, or the formation of frank bullae causing tinea corporis bullosa [10].

Tinea faciei has a broad range of presentations. Infection may begin as flat, scaly macules that develop a raised border that advances outward in all directions, with or without the development of papules, vesicles, and crusts (Fig. 21.5) [11]. Due to a lack of a correct diagnosis and the use of topical steroids, lesions may not be annular. The central area may become hypo- or hyperpigmented. Lesions may occur singly or in multiple patches, and can extend to other sites [11, 22].

Fig. 21.5

Tinea faciei

Tinea imbricata or Tokelau is a chronic tinea of glabrous skin caused by Trichophyton concentricum, an anthropophilic dermatophyte. It presents as distinctive scaly, concentric, overlapping plaques that typically begin on the face and spread, involving large areas of the body [23]. This infection is endemic in Polynesia, and in Central and South America; particularly in rural areas.

Tinea Capitis

Infection of the scalp involves hyphal proliferation in the stratum corneum that extends into the hair follicle orifice and hair shaft [1]. This clinical form is caused by the exposure of the scalp to the inoculum from an infected individual, animal, or contaminated soil [1].

Noninflammatory or epidemic tinea capitis may begin as a small erythematous papule around the hair shaft which spreads outward, developing fine scaling in noticeable patches (Fig. 21.6) [1]. Partial or complete alopecia may result because brittle hair breaks off a few millimeters from the scalp. Affected hair may appear grey due to a coating of fungi. Noninflammatory infection is associated with M. audouinii and Microsporum ferrugineum; however, T. tonsurans and M. canis may sometimes cause noninflammatory infection.

Fig. 21.6

Noninflammatory tinea capitis

Black dot tinea capitis is most frequently associated with T. tonsurans or T. violaceum infection, and results from hair breakage at the level of the scalp, showing diseased hair in the follicle as a “black dot” [1]. Scaling is typically present with little inflammation, though inflammatory kerion, which are characterized by an oozing mass with pustules, loose hair, and discharge of pus are possible [1]. Signs of systemic illness may be present, including fever and lymphadenopathy.

Inflammatory tinea capitis is associated with zoophilic or geophilic species such as M. canis or Microsporum gypseum, but may also occur with T. verrucosum, Trichophyton schoenleinii, T. tonsurans, and M. audouinii [1].

Onychomycosis

The most common presentation of onychomycosis is distal lateral subungual onychomycosis (DLSO), which presents as a nail with discoloration and varying degrees of hyperkeratosis, onycholysis (separation of nail from nail bed), subungual debris, and thickening [25, 26] (Fig. 21.7). DLSO begins at the distal edge of the nail (hyponychium) and travels proximally through the stratum corneum of the nail bed, involving the nail plate (Fig. 21.8). The most severe grades of DLSO may progress to total dystrophic onychomycosis (TDO) where the nail plate becomes friable and crumbles away to a varying degree, leaving an exposed thickened nail bed and subungual debris. Within the spectrum of DLSO presentations, infections may spread relatively evenly across the nail plate. Alternatively, infection may penetrate only the lateral edge or edges of the nail (lateral infection), or may penetrate longitudinally in a “spike” formation [27]. Infection may also develop as a dermatophytoma, where debris and fungi clump densely to form a thick, hyperkeratotic mass [27]. These presentations may not respond well to therapy.

Fig. 21.7

Top left and right—onychomycosis; bottom left—onycholysis; bottom right—psoriasis

Fig. 21.8

Routes of infection causing the typical presentations of onychomycosis

Sometimes, infection may present as superficial white onychomycosis (SWO), proximal subungual onychomycosis (PSO), or endonyx onychomycosis [25, 26]. SWO involves infection of the superficial nail plate, showing patches of white discoloration on the nail surface. Multiple nails may be affected, and varying degrees of nail plate area may be covered (Fig. 21.9). The rare presentation PSO results from invasion of the proximal nail fold and extending distally along the underside of the nail plate as a white patch of infection (Fig. 21.10). PSO is more common in immunodeficient individuals, such as HIV-positive patients. It may serve as a hallmark for immunodeficiency [28]. Endonyx presents as a diffuse milky white discoloration of the nail in the absence of hyperkeratosis and onycholysis, with the nail plate surface and thickness remaining normal [25]. The nail plate may show lamellar splitting with invasion of the superficial and deep layers of the nail without excessive thickening or discoloration [26]. Endonyx infections are usually caused by Trichophyton soudanense or T. violaceum [25, 26].

Fig. 21.9

Typical presentation of superficial white onychomycosis (SWO) on the third toenail with distal lateral subungual onychomycosis (DLSO) presented in the great toenail

Fig. 21.10

Proximal subungual onychomycosis (PSO) developed during occlusion by the neighboring digit

Pityriasis Versicolor

Pityriasis versicolor presents as well-defined lesions with fine scales caused by desquamation. These are either hyperpigmented (pink, tan, dark brown, or black) or hypopigmented (white, or lighter than normal skin). Hypopigmentation may not always exhibit scaling (Fig. 21.11) [29]. It is a superficial fungal infection that is largely asymptomatic, with the exception of occasional mild pruritus [6]. There is a large variation in lesion size from macules to entire trunk coverage [30]. Lesions are predominant in areas with a high number of sebaceous glands such as the scalp, chest, and back, as well as the upper arms and face [6, 29]. Facial lesions are more common in children [3]. Hypopigmentation may occur independently or following the hyperpigmented stage [29].

Fig. 21.11

Tinea versicolor showing hyperpigmented lesions (upper photos) and hypopigmented lesions (lower photo)

Seborrheic Dermatitis

Seborrheic dermatitis presents as red, flaking, greasy-looking patches of skin on the scalp and hair-bearing areas of the face such as the nasolabial folds, eyebrows, and ears (Fig. 21.12) [16]. SD is a more severe form of dandruff involving body sites of abundant sebaceous gland activity. It may occur on the groin, axillae, anterior chest, or inside/behind the ears [16, 31]. Dandruff can appear as loosely adherent white or gray flakes, while severe SD may be thick, oily, yellow–brown crusts. Pruritus, irritation, and a tight, dry feeling may be associated with the afflicted area [32]. Some cases present with little erythema, while others present as a sore scalp with occasional pustules [15].

Fig. 21.12

Seborrheic dermatitis—severe presentation

Diagnosis

Definitive diagnosis of tineas requires confirmation of dermatophyte organisms by microscopic examination and laboratory fungal culture methods. For skin infections, scrapings or swabs can be taken from the leading edge of a lesion. Nail clippings and subungual debris can similarly be obtained. Direct examination with 15 or 20 % potassium hydroxide (KOH) is undemanding, economical, and fast and its initial results allow the physician to establish treatment. KOH is added to the samples to dissociate hyphae from keratinocytes. In dermatophytosis, direct examination can demonstrate the existence of hyphae or arthroconidia. [33].

In tinea versicolor, direct mycological examination can reveal the typical “spaghetti and meatball” (mixture of yeasts and short hyphae) appearance. In piedras, microscopic examination may show mycotic nodules. When clinical samples are of good quality and the observer is experienced, KOH has a high sensitivity; unfortunately, the test has a low specificity because it fails to identify the genus and species [34]. KOH examination of hairs may help differentiate types of tinea capitis infection. Ectothrix infection can be distinguished from endothrix infection because in the former arthroconidia appear as chains on the surface of the hair shaft or as a mosaic sheath around the hair [1]. Inspection under Wood’s light (filtered ultraviolet light with a peak of 365 nm) may aid in diagnosis [1]. Ectothrix infections with M. audouinii, M. canis, and M. ferrugineum show bright green fluorescence under the Wood’s light. T. schoenleinii shows dull green fluorescence. T. tonsurans, however, does not fluoresce, and the utility of the Wood’s lamp for diagnosis is currently limited in countries where this is the major infecting agent.

Cultures are essential to establish an accurate identification of the causative microorganism. Species identification is established by the macroscopic and microscopic characteristics of the culture, but it has a low sensitivity and a high specificity. In addition, a 1–4-week turnaround time and substantial mycological expertise are needed when performing identification. Typical dermatophyte strains can be frequently recognized from primary cultures, but subcultures on specific media are usually required. Potato dextrose agar is used most frequently for enhancing sporulation and producing pigments. Biochemical and physiological tests such as urease activity, in vitro hair perforation test, and nutritional requirements tests are currently not used [35].

Molecular methods have been expanded, and are more rapid and specific for conventional identification. Young et al. developed a multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for the identification of dermatophytes. Using three sets of primers (ITS1-2, 18S rRNA, and 28S rRNA), they effectively recognized 11 standard dermatophyte strains. This method was applied to clinical samples of 73 patients diagnosed with fungal disease. The etiological agents were T. rubrum (94.5 %), T. mentagrophytes (1.4 %), T. tonsurans (2.8 %), and M. gypseum (1.4 %) [36]. A real-time (RT) PCR based on ITS1 sequences was developed to identify 11 dermatophyte species obtained from superficial samples. It was shown to be highly sensitive and specific for direct detection of dermatophytes in clinical material. RT-PCR seems to be very appropriate as a routine diagnostic assay for dermatophytosis [37]. Sato et al. applied a simple PCR-based DNA microarray method for the detection of pathogens directly from nail material. One hundred and six onychomycosis materials were collected and corroborated for the presence of fungal elements by microscopy. Culture of the samples yielded growth in only 36. Using their PCR-based DNA microarray, they identified the species in 98 specimens [38].

Diagnostic methods in medical mycology have been changing and new techniques are an improvement over former conventional procedures. We now have optional molecular methods for rapid identification of pathogenic fungi, establishing treatment and determining epidemiological trends with more certainty.

Treatment

Treatment for superficial fungal infections varies widely. Antifungal medications that are used typically belong to the azole or allylamine drug classes (Table 21.2). Topical antifungals are effective in circumscribed areas of the skin surface. Some topical antifungals exhibit anti-inflammatory and antibacterial effects as well as antifungal activity, and are indicated for infections with inflammation and potential bacterial infection. Available oral antifungals include griseofulvin, terbinafine, itraconazole, fluconazole, albaconazole, and ketoconazole. These agents are indicated in severe or widespread infection as well as for immunocompromised patients where a prompt, thorough resolution of infection is necessary. They can also be used as an alternative to daily topical therapy.

Table 21.2

Treatment options available for dermatophytoses and other superficial fungal infectionsa

Terbinafine | Itraconazole | Fluconazole | Ketoconazole | Griseofulvin | Topicals | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Tinea pedis/manuuma | b Cream: apply twice daily × 1–4 weeks | Oral: 200 mg bid × 1 week | Oral: 150 mg once weekly × 2–6 weeks | b 2 % Cream: apply once daily × 6 weeks | Microsize b: 1 g/day | bCiclopirox 0.77 % cream or gel: twice daily × 4 weeks | bClotrimazole, bMiconazole, bButenafine, bEconazole |

b1 % Solution: apply twice daily × 1 week | Oral b: 200–400 mg/day ×> 4 weeks (seldomly used) | Ultramicrosize: 660 or 750 mg/day × 4–8 weeks | Antifungal powder for prevention | ||||

Oral: 250 mg/day × 2 weeks | |||||||

Tinea corporis/cruris | b Cream: apply twice daily × 1–4 weeks | Oral: 200 mg/day × 1 week | Oral: 150–300 mg once weekly × 2–4 weeks | b 2 % Cream: apply once daily × 2 weeks | b Microsize: 500 mg/day | bCiclopirox 0.77 % cream or gel: twice daily × 4 weeks | Clotrimazole Miconazole, Butenafine, Econazole |

b 1 % Solution: apply twice daily × 1 week | b Oral: 200–400 mg/day × 4 weeks (seldomly used) | Ultramicrosize : 330–375 mg/day × 2–4 weeks | |||||

Oral: 250 mg/day × 2–4 weeks | |||||||

Tinea capitis | Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

| ||||||