Dental Oncology and Maxillofacial Prosthetics

Theresa M. Hofstede

Jack W. Martin

James C. Lemon

Mark S. Chambers

In caring for head and neck cancer patients, most treatment centers use a team approach. By doing this, each involved discipline (e.g., surgery, radiotherapy, dental oncology, chemotherapy, and speech pathology) determines its role for an enhanced treatment outcome. Rehabilitation of function, aesthetics, and prevention of infection should be a major concern before treatment and following the elimination of disease in the patient with head and neck cancer. Patients with head and neck cancer should be referred to an oncologic dentist or maxillofacial prosthodontist during their initial medical workup for evaluation of their oral and dental health. The results of this evaluation can then be integrated into the primary treatment plan. Early dental intervention can optimize outcome and decrease morbidities such as radiation-induced osteoradionecrosis and chemotherapy-induced systemic infection. Early intervention and planning can also allow surgically removed anatomic structures, such as the maxilla, to be immediately replaced with a prosthesis during the primary ablative procedure.1,2

ORAL AND DENTAL ANATOMY

Surgeons, radiation oncologists, and medical oncologists, who treat patients with head and neck cancer, should be familiar with oral and dental anatomy so that they can accurately communicate with their dental colleagues. Adult teeth are routinely used as landmarks to document the location of tumors of the jaws and to plan intraoral resections and prosthetic procedures before and after surgery. A commonly used scheme for this purpose is the universal numbering system, which is used in the United States to identify the position and type of adult teeth. In this system, adult teeth are numbered sequentially from 1 to 32 (in both the maxilla and the mandible), starting with the right maxillary third molar and proceeding around the arch to the left third molar, down to the left mandibular third molar, and then around the mandibular arch to the right third molar. Missing or impacted teeth are counted in this system.3 The FDI World Dental Federation Notation (International) is used elsewhere in the world. This system divides the mouth into four quadrants: (a) maxillary right quadrant; (b) maxillary left quadrant; (c) mandibular left quadrant; and (d) mandibular right quadrant. The teeth in each quadrant are then numbered from 1 (central incisor) to 8 (third molar).

The retained, nondiseased anatomic structures of the maxilla and mandible are important for retention and support of prostheses used in rehabilitation of patients with head and neck cancer. In the maxilla, the tissues important for the support and retention of prostheses are the maxillary tuberosity, alveolar ridge, and hard palate. In the mandible, the major supporting structures are the alveolar ridge, retromolar pad, and buccal shelf. Sound and periodontally healthy teeth in both arches are very important in retention and support of prostheses. Conservation of the supporting tissue, without compromising oncologic principles used in the eradication of disease, should be a goal of the surgeon and medical oncologist.4,5

ORAL AND DENTAL EVALUATION

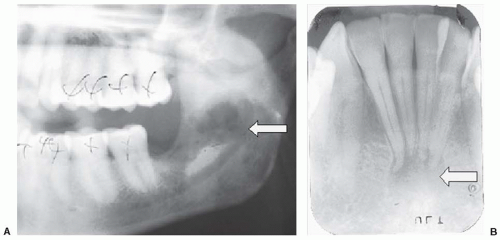

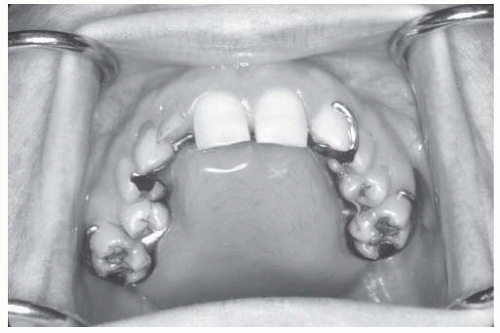

Throughout treatment and follow-up care, the surgeon, radiation oncologist, and medical oncologist should be able to recognize oral pathology secondary to poor dental status, for example, advanced periodontal disease, gross dental caries, tissue irritation secondary to poorly fitting prostheses, and poor oral hygiene. Plaque and calculus formation on teeth is an indication of poor oral hygiene. Preliminary findings of the initial medical examination should be noted. Patients require a pretreatment evaluation by an oncologic dentist, who should do a thorough radiographic and oral/dental examination and make impressions of dental and facial structures as appropriate. Panoramic, periapical, bitewing, and occlusal radiographs can be diagnostic and are inexpensive and easily obtained in the dental office (Fig. 9-1).6 Stone casts obtained from impressions of the maxilla, mandible, and facial structures can be useful in treatment planning, surgical prosthesis fabrication, and posttreatment rehabilitation. Compromised teeth with a poor prognosis should be extracted before irradiation or chemotherapy (Fig. 9-2). This may require general anesthesia or intravenous sedation with local anesthesia depending on the difficulty of dental surgery and the patient’s mental and physical status. Performing dental surgical procedures at the time of the primary ablative procedure will reduce any delay before starting adjunctive treatments such as radiotherapy or chemotherapy. However, appropriate healing time is recommended prior to beginning chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Eliminating sites of infection decreases the chances of osteoradionecrosis in patients who undergo radiotherapy and infectious episodes in patients who receive chemotherapy.7

For the first year after cancer therapy, patient follow-up by the oncologic dentist is vital. Patients treated with radiotherapy to the head and neck may experience dry mouth (xerostomia) and a subsequent increase in oral or dental problems such as infection, periodontal disease, and dental caries. All members of the treatment team should understand the importance of fluoride

and at each follow-up appointment should encourage the patient to use daily fluoride therapy.8,9,10 In many instances, patients can be referred back to their general dentist for routine dental care after the initial posttreatment period.

and at each follow-up appointment should encourage the patient to use daily fluoride therapy.8,9,10 In many instances, patients can be referred back to their general dentist for routine dental care after the initial posttreatment period.

In summary, a thorough primary, oral, and dental evaluation by an oncologic dentist documents the oral and dental pathology and allows for appropriate intervention before cancer treatment is started. The results of the oral/dental evaluation enable the treatment team to inform the patient about rehabilitation, reduce or eliminate the sites of potential infection, and reveal important information that will be useful during treatment and rehabilitation. To ensure an appropriate level of continued oral care, a dentist should be included as a member of the treatment team.11

INTRAORAL PROSTHETIC REHABILITATION

Three phases of prosthetic rehabilitation exist in most cases: surgical, interim, and definitive. Each phase may span several months to 1 year or more, depending on the size and location of the tumor and on the type of treatment required. Initially, surgical and interim prostheses may require frequent follow-up appointments and adjustments. Patients who undergo surgery that involves the maxilla and sinus may experience nasal regurgitation of food and liquids from the mouth into the nose. During and following treatment, meticulous oral and dental hygiene is important as a life-long therapy. Physical therapy may also be necessary to maintain oral opening and prevent trismus.

Maxilla

Malignant and benign tumors involving the maxillary sinus, hard palate, and upper alveolus often require surgical resection with an infrastructure maxillectomy procedure. The resultant surgical defect is an oral-nasal and/or oral-antral communication, which may cause substantial postoperative speech and swallowing problems. These defects often require prosthetic obturation. Surgical considerations that may improve prosthetic rehabilitation of patients who receive a maxillectomy are described in detail in the following text. In a dentate patient, the head and neck surgeon should make the alveolar osteotomy through the socket of an extracted tooth to preserve bone support around the terminal tooth. In cases in which cuts are made between teeth, both teeth may be lost. The palatal osteotomy should conserve as much of the supporting tissue as possible, for example, premaxilla, tuberosity, and alveolar ridge, consistent with oncologic principles. If possible, a split-thickness skin graft (STSG) should be placed in the maxillary defect. A well-placed STSG reduces postoperative secretions, facilitates oral hygiene, provides a sound tissue base for a prosthesis, and creates a scar band for greater retention of the prosthesis. The palatal mucosa, if it is not affected by disease, can be retained and used to line the midline portion of the palatal cut. This tissue is extremely resistant to the abrasive forces of the prosthesis.

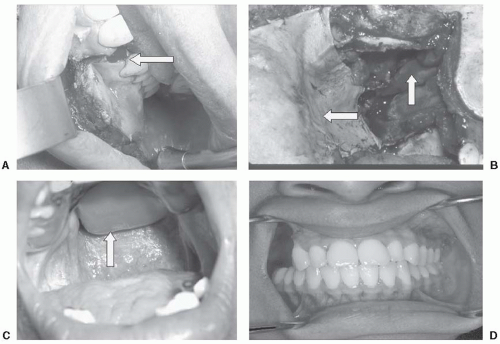

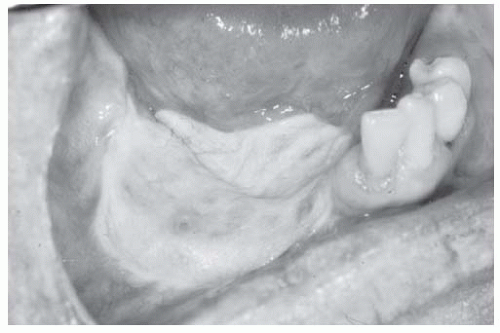

The inferior and middle turbinates should be removed to allow extension of the prosthesis into the defect area and will ensure a good prosthetic seal. Mandibular molar teeth on the side of the maxillectomy should be considered for extraction if the opposing maxilla and teeth are resected. These teeth can pose a hygiene problem and are essentially nonfunctional after a posterior maxillectomy. This problem is particularly significant when the resection extends inferiorly in the buccal mucosa. When possible, the maxillectomy should be performed intraorally, thereby eliminating the facial incision and resulting disfigurement (Fig. 9-3).12

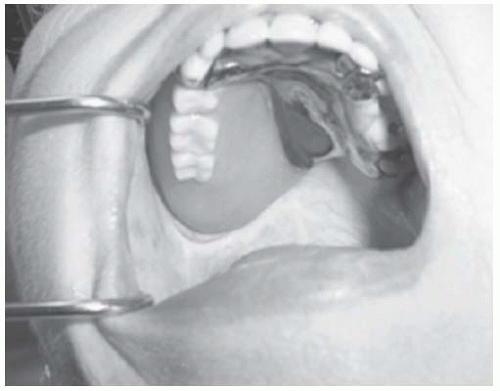

A surgical obturator prosthesis placed at the time of the ablative procedure reestablishes the palatal contour, restoring speech and swallowing function. This prosthesis also supports the surgical packing and skin graft in position. The surgical obturator can be ligated to the remaining teeth with a 24-G ligature wire or retained with a bone screw in the edentulous patient. The surgical obturator prosthesis may allow the patient to speak and swallow almost immediately after surgery and, in turn, may obviate the need for a nasogastric tube (Fig. 9-4). The prosthesis maintains proper lip and cheek support during initial healing and therefore increases resistance to the contracture and subsequent facial deformity or scar tissue. Patients scheduled for maxillectomy should be referred to an oncologic dentist (presurgical) during their initial oncologic evaluation to ensure adequate time for fabrication of this prosthesis.13

An interim obturator prosthesis is placed immediately after the surgical obturator and packing are removed, usually 5 to 8 days postsurgery. The interim obturator prosthesis has an extension that obturates the oral nasal/antral defect. This extension is created with a soft, moldable denture tissue conditioning

material, and is modified as necessary to accommodate healing during the initial healing phase (Fig. 9-5). A minimum of five to ten appointments may be needed to adjust and modify the prosthesis during this distinct phase of rehabilitation.14

material, and is modified as necessary to accommodate healing during the initial healing phase (Fig. 9-5). A minimum of five to ten appointments may be needed to adjust and modify the prosthesis during this distinct phase of rehabilitation.14

A definitive obturator prosthesis is made after the surgical defect has stabilized, approximately 6 months after the surgery. This prosthesis allows for enhanced aesthetics and function. The average lifespan of the definitive obturator prosthesis is 3 to 5 years, and close follow-up with adjustments is important to ensure continued accurate fit and comfort (Fig. 9-6).15

FIGURE 9-6. Definitive obturator prosthesis in place. This prosthesis maximizes function and aesthetics. |

Microvascular free-flap surgical reconstruction of the maxilla in patients treated with a maxillectomy is becoming increasingly common. In some cases the use of free flaps may be an excellent alternative to the prosthetic obturator prosthesis, whereas in others this option may not offer acceptable aesthetic or functional results. Older adults, mentally challenged individuals, and those who have lost the dexterity to place and remove a prosthesis should be considered for free-flap reconstruction. Prosthetic rehabilitation after freeflap reconstruction may be difficult due to bulkiness and mobility of the flap. Patients who demand a functional and aesthetic restoration after reconstruction with a free flap should be referred to a maxillofacial prosthodontist before the procedure so that information concerning rehabilitation can be considered before the procedure.16

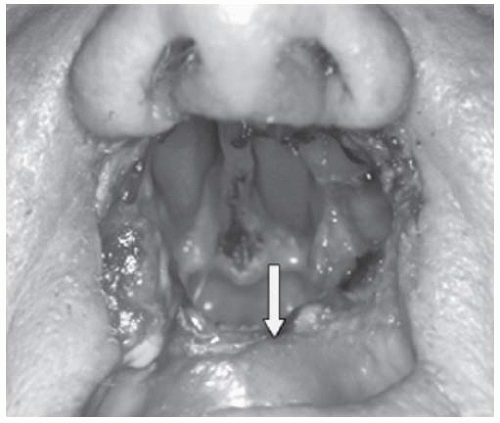

Soft Palate

When the soft palate is involved in the surgical procedure, the surgeon must consider whether the remaining soft palate will be useful in prosthetic rehabilitation. In most cases, any remaining soft palate that is nonfunctional should be completely removed. Removal of the soft palate allows easy access to the pharynx for fabrication of the pharyngeal obturator prosthesis. Occasionally, a thin strip of soft palate can be vitally important for prosthesis retention in patients with limited supporting tissue (teeth, hard palate), such as when a bilateral total maxillectomy has been completed (Fig. 9-7).17 In cases where the resection of the soft palate is anticipated, an intraoperative dental consultation may be indicated. Primary radiation treatment of the soft palate may cause muscle fibrosis leading to incompetency of the soft palate. In this situation, prosthetic rehabilitation may be impossible because of poor access to the oropharynx. In some cases, surgical removal of the soft palate may be required before prosthetic rehabilitation. Prosthetic rehabilitation may not restore the pretreatment speech and swallowing function because of radiation-induced fibrosis and limited movement of the muscles of the pharyngeal walls. These muscles are important in compensating for the missing soft palate by contacting the pharyngeal obturator during speech and swallowing.18

Mandible

Patients requiring a mandibulectomy may need surgical stents to assist the surgeon in realignment of the residual mandible before reconstruction. These stents are custom-made and require preoperative fabrication. Reconstruction plates are medical devices used during the resection and reconstruction of mandibles. The reconstruction plate holds the remnants of the mandible/condyle in its preresected position and attaches to the bony segments of the microvascular flap. This optimizes appropriate mandibular contours and function. These plates must be precisely bent onto the preresected mandible, attached with reconstruction screws, and then removed prior to the resection. Reattachment in the same position later with the microvascular flap ensures accuracy. Intermaxillary fixation with arch bars may also aid in realignment and stabilizing the mandible during reconstruction.19 The maxillary teeth opposite the mandibular reconstruction may need to be extracted to prevent trauma to bone and soft tissue flaps. In cases in which reconstruction is not being considered for a patient who has received a mandibulectomy, removal of the remnant condyle and ramus on the affected side prevents migration of these structures medially toward the maxilla. Such migration can make prosthetic rehabilitation more difficult and add more frustration to the patient.20

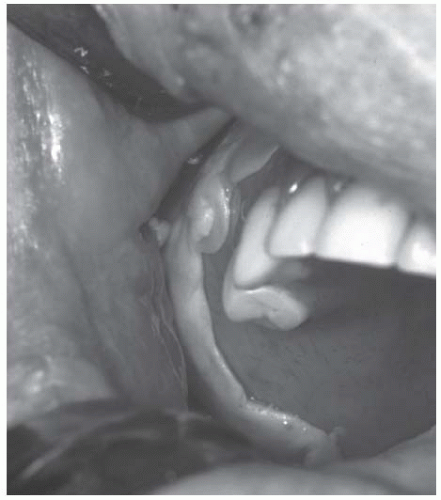

In general, soft tissue coverage of the mandible when free flaps are used does not provide adequate supporting tissue for prosthetic rehabilitation (Fig. 9-8). Vestibuloplasty is a surgical procedure designed to restore alveolar ridge support by reducing the attachment of muscles to the buccal, labial, and lingual aspects of the jaw and thinning the existing tissue, such as flaps used in the initial reconstruction. STSGs are important because they provide a sound tissue base for a prosthesis and can also be used to separate the floor of the mouth from the buccal mucosa (Fig. 9-9).21 When the tongue is sutured to the buccal or labial mucosa, prosthetic rehabilitation is limited if not impossible. As with the maxilla, conservation of the supporting tissue in the mandible, consistent with removal of disease, is important. Dental implants can be placed in the nonirradiated native or reconstructed mandible and may be critical to the stability and retention of the mandible prosthesis. Maxillary and mandibular resection dentures can be fabricated for patients who do not receive reconstructive surgery after mandibulectomy.

Tongue

Speech and swallowing dysfunction are common problems in patients following glossectomy. Tumors of the oral cavity often involve contiguous structures and resections within the floor of the mouth and are likely to involve the tongue and muscle attachments, or innervation. The ultimate treatment goal is maximum restoration of speech and swallowing, which may require the combination of soft tissue and prosthetic reconstruction.

FIGURE 9-8. Fibula reconstruction of mandible with skin paddle is reconstructing floor of mouth and covering mandible. This skin paddle is movable, thick, and not satisfactory for prosthesis support. |

FIGURE 9-9. Fibula reconstruction of mandible with split-thickness skin graft vestibuloplasty and dental implant placement. Patient is now ready for prosthetic rehabilitation. |

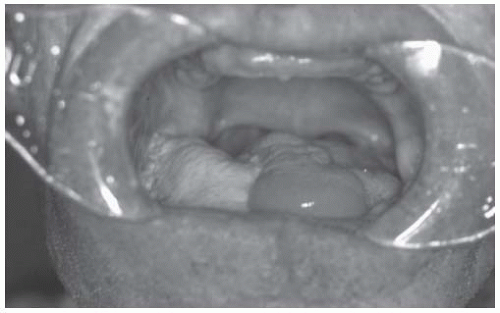

Palatal augmentation prostheses are removable palatal prostheses that reshape the hard palate to improve contact between the residual tongue and the palate during speech and swallowing (Fig. 9-10). These prostheses improve speech and swallowing function due to impaired tongue mobility as a result of surgery, trauma, or neurologic/motor deficits. Resection sites that are most likely to affect oral components of speech and swallowing are the oral tongue, anterior or posterior mandible, floor of the mouth, and base of the tongue.22

The greatest improvement in function with palatal augmentation prostheses results when movement of the residual tongue tissue is retained. Replacing lost tissue bulk with soft tissue may obliterate some of the space that cannot be controlled by the limited range of motion of the tongue. Patients with the greatest movement of the residual tongue benefit the most from the augmentation

prosthesis, and patients with a mobile tongue tip have the best function. The use of thinner microvascular flaps for closure of the surgical site allows the residual innervated portion of the tongue to function with minimal impairment of movement. The palatal augmentation prosthesis offers rehabilitation advantages for patients with impaired function of the tongue.

prosthesis, and patients with a mobile tongue tip have the best function. The use of thinner microvascular flaps for closure of the surgical site allows the residual innervated portion of the tongue to function with minimal impairment of movement. The palatal augmentation prosthesis offers rehabilitation advantages for patients with impaired function of the tongue.

Oral Hygiene Procedures

Oral hygiene is one of the most important aspects of postoperative care. Initially, the surgical defect should be irrigated with an irrigation system, that is, bulb or syringe irrigation or powerspray units. After initial healing, a power-spray unit such as Water Pik (Teledyne Dental, Buffalo, NY) can be used by the patient. The patient should be instructed in the proper use of the lavage system. Initially after surgery, the patient should rinse three times a day with a saline solution made by adding one teaspoon of salt and one teaspoon of sodium bicarbonate to 16 oz of water. The irrigation system must provide enough pressure to ensure that the rinse reaches all parts of the surgical defect. Routine dental hygiene, that is, tooth brushing and flossing should be started as soon as possible. Patients are usually apprehensive about resuming the brushing and flossing of teeth because of concerns that doing so may harm the surgical site. However, if healing proceeds normally, using a power-spray system (low setting) beginning 4 weeks after surgery should not pose a problem. During the fourth week of healing, a 1:1 dilution of 3 % hydrogen peroxide in water can be added to the oral hygiene routine. A sponge-tipped applicator (e.g., Oral-Swab, Crystal Lake, IL) may be used to clean the skin graft portion of the defect. After the surgical site has been cleaned, the entire oral cavity including the teeth, the tongue, the cheek, and the remaining hard palate is cleaned.13,23

Physical Therapy

Conventional oral physiotherapy (i.e., mouth opening exercises) should be performed during and after radiation treatment, especially if the pterygoid regions are included in the radiation treatment fields.24 If a restricted mouth opening is noted following surgery, tongue blades stacked on each other can be inserted between the posterior teeth until maximum opening is obtained. The blades are held in place for several minutes to allow the forming scar tissue to stretch, and then another tongue blade is added until a pain threshold is reached.

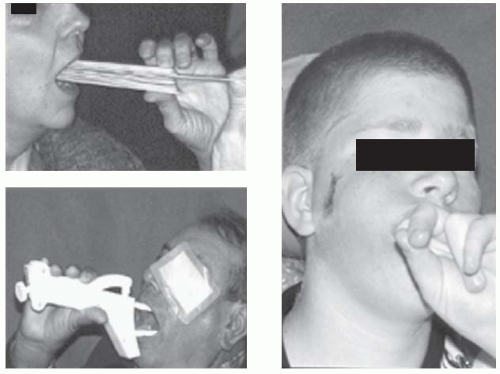

Various passive and active commercial devices to aid in mouth opening are available. Two such devices are the Therabite mouth opener (Atos Medical, Milwaukee, WI) and the Dynasplint (Dynasplint Systems Inc., Severna Park, MD). These devices open the mouth vertically with a manual separation of the jaws or a prolonged stretch (Fig. 9-11). Each of these devices is customized to the patient and has advantages and disadvantages. Users of these devices must follow manufacturers and physical therapy guidelines and ensure that teeth do not incur orthodontic tooth movement or damage. The edentulous patient can use his or her fingers, placing them between the maxillary and the mandibular ridges, to pry open the mouth. The exercises can be combined with extraoral palpation and stretching of the cheek and upper lip to keep the tissue as pliable as possible. During the first 4 weeks, the patient should be instructed to do these stretching exercises three or four times a day (15 minutes each session). In addition, a trained physical therapist can institute more advanced means of physical therapy, such as electrotherapy, ultrasound therapy, and isometric exercises. Daily mouth opening measurements should be recorded to help both the clinician and the patient measure progress resulting from these exercises, that is, rulers or calipers measuring vertical dimension between the maxillary and the mandibular incisors or ridges. In many cases, these physiotherapy techniques should be continued for at least 1 year. If a patient has a sudden loss of mouth opening, the dentist should immediately suspect and rule out recurrence of disease or infection.25

OSSEOINTEGRATED DENTAL IMPLANTS

Osseointegrated implants have been used widely in dental rehabilitation since the 1980s. However, indiscriminate placement of these implants can decrease their effectiveness and increase the cost of rehabilitation dramatically. In patients with a normal mandible and maxilla, the success rate of osseointegration is between 90% and 95%.26 However, in patients with a reconstructed mandible, the success rate may be lower, depending on

the quantity and quality of the recipient bone. Careful planning is required before an implant is placed in any patient.

the quantity and quality of the recipient bone. Careful planning is required before an implant is placed in any patient.

Implants may be the only means by which some maxillofacial prostheses can be retained, particularly those placed over osteocutaneous flaps. Patients who have undergone a free fibula tissue transfer placed using microvascular techniques make excellent recipients of implants. The fibula’s bicortical configuration and vertical height are ideal for endosteal implant placement. Vertical height of the fibula averages 15.2 mm, which is ideal for the standard-sized implant.27 The number, positioning, and spacing between implants is critical in prosthesis fabrication. These details are best dealt with after reconstructive surgery, in a separate procedure, when a surgical stent made by the dentist responsible for rehabilitation can help guide the surgeon in the exact alignment and positioning of the implants. The information needed to obtain proper fit and positioning of prostheses can be determined only by postoperative evaluations. Some implant systems require two-staged surgical procedures, whereas others require only one stage. The type of implant used should be the choice and responsibility of the dentist responsible for the prosthetic rehabilitation of the patient (Fig. 9-12).28 Patients requiring postoperative radiation may not be candidates for implants if placed in the volumes of tissue radiated. This subject is discussed later in the chapter in the section “Care of Patients with Head and Neck Cancer Treated with Radiation.”

EXTRAORAL IMPLANTS

In the beginning of 1993, one extraoral implant system had been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA); however, more have been approved since then and are currently available. Like many of their intraoral counterparts, extraoral implants are placed in two stages; however, the extraoral implants should heal unloaded for 4 to 6 months to allow adequate time for integration. Extraoral implants can be of great benefit for retention and stability of facial prostheses when correctly placed, but do not always guarantee a successful prosthesis.29 Other retention systems available for facial prostheses are adhesives and tapes. Undercuts in the defect, if properly prepared, can also be used to retain prostheses. When contact between intraoral and extraoral defects results from surgery, the facial portion of the prosthesis can be retained through its attachment to an intraoral component.

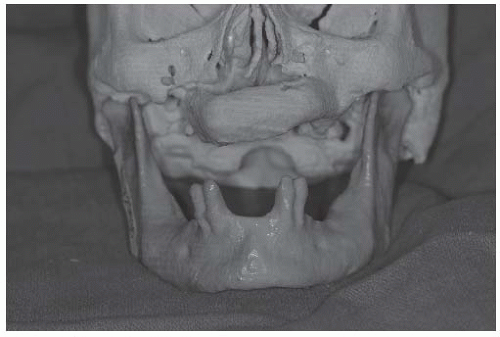

RAPID PROTOTYPING

Rapid prototyping is an automated construction of objects with three-dimensional printers, stereolithography machines, or laser sintering devices that are useful in dental implantation. The first rapid prototyping techniques were developed in the 1980s and were used to fabricate prototypes of tools and parts.30 Currently, it is used in the biologic sciences to create dimensionally accurate models of anatomic structures. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging can be used to transform medical images into resin replicas of skeletal anatomy. A three-dimensional model of an ablated site in the head and neck region can be used in preoperative planning or surgical stent fabrication or to create a template for implant placement. In addition, rapid prototyping provides an accurate spatial reference during surgery (Fig. 9-13).30,31

FACIAL PROSTHETICS

In general, a successful facial prosthesis is aesthetically pleasing, retentive, and tissue compatible. In addition, a prosthesis should be simple in design so that the patient can place and remove it easily. Materials used in constructing facial prostheses should be easy to clean, color stable, resistant to bacterial and fungal growth, durable, and well tolerated by tissues. The two materials that meet these criteria most fully are methylmethacrylate (plastic) and medical-grade silicones. Extraoral prostheses may be combined with intraoral prostheses to enhance retention and aesthetics.

General Rehabilitative Principles for Ablative and Reconstructive Surgery Involving Facial Structures

General Principles. Numerous general surgical principles can be applied to placement of prostheses at all facial sites. Although basic, these principles are extremely important in ensuring the success of facial prostheses:

Smooth and round off all bony margins at the conclusion of the ablative procedure.

Place an STSG on any exposed bone or periosteum that is not covered with free tissue or a pedicle flap.

Remove unsupported tissue tags.

Take replacement tissues from areas that best match the tissues surrounding the recipient bed.

When using free tissue transfer flaps or pedicle flaps to repair the surgical defect, take care not to overbulk the surgical site in a patient for whom a prosthesis is planned.

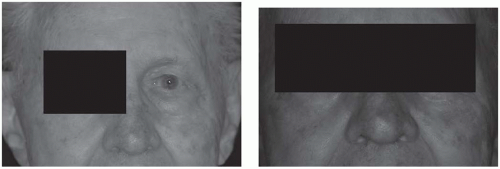

Orbit. When the orbital contents are removed in conjunction with a maxillary resection, reconstruction of the infraorbital rim improves the facial contour and enhances the prosthetic rehabilitation. This reconstruction can be accomplished by using a microvascular reconstruction with bone. If the bony structures of the orbit are left intact, an STSG can be placed in the defect, thereby allowing a prosthesis contact with the tissue at the depth of the defect (Fig. 9-14). Care must be exercised in placing the STSG so that the normal position of the eyebrow is maintained. Alternatively, microvascular reconstruction can be used to obliterate the defect entirely.

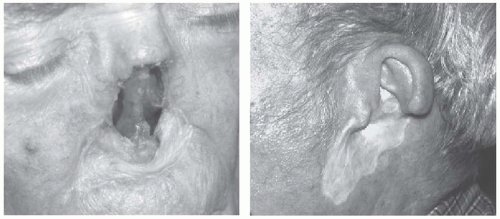

Nose. Patients who undergo partial or total rhinectomy can be adequately rehabilitated using a removable prosthesis. An STSG should be placed in the defect to stabilize the borders of the defect and to maintain a normal lip position. For patients undergoing total rhinectomy, it is especially important that the inferior border of the nasal defect be fixated and that a dam at the inferior border of the defect be created. If the defect cannot be skin grafted, the surgeon should consider positioning the mucocutaneous junction as far posteriorly into the defect as possible. This measure will fixate the border and help form a dam. If possible, the nasal spine should be spared and the mucosa of the septum covered with a skin graft.

Ear. The superior rim and tragus should be spared if possible (Fig. 9-15). If supported by cartilage, the superior rim can be used to support eyewear. The tragus can be used to hide anterior margins to improve aesthetics. The STSG can tolerate tissue adhesives used to retain facial prostheses and will also improve hygiene.32

Midface. To enhance prosthetic rehabilitation at midface sites, several special considerations must be made before and during the reconstructive procedure.29 During the ablative procedure, the surgical team should conserve as much of the maxilla and associated structures as possible. Respiratory mucosa should be removed from the remaining vomer, nasal floor, and sinuses, and a STSG should be placed.21 The STSG will allow extension of the removable facial prosthesis into these areas if this extension later becomes necessary and will stop secretions from the replaced respiratory mucosa (crusting), thereby improving overall hygiene.33

A free-flap reconstruction with bone can be placed to improve the retention and support of the facial prosthesis. Sufficient space for this purpose is critical because if the graft is placed too far anteriorly, the aesthetics of the facial prosthesis can be diminished. If the reconstruction infringes on this space, placement of the prosthesis may be impossible. In this case, another surgical procedure to reposition the graft would be needed before prosthesis fabrication. The free-graft reconstruction should be done after irradiation if implants are indicated. Once bone is irradiated, its capacity for implant placement and subsequent osseointegration is severely diminished or lost because its osteogenic potential and microvascularity are decreased.34

CARE OF PATIENTS WITH HEAD AND NECK CANCER TREATED WITH RADIATION

The clinical use of radiation is a complex process involving many professionals and a variety of interrelated functions. The aim of radiation therapy is to deliver a precisely measured dose of radiation to a defined target volume, thereby eradicating the tumor while causing minimal damage to surrounding healthy tissue.35 More than 80% of patients diagnosed with advanced head and neck cancer receive a course of radiation therapy as a component of their treatment.

Radiation Stents

The use of conformal radiotherapy treatment helps to minimize radiation dose to the adjacent normal oral structures. Despite this, side effects to the adjacent tissues continue to be common. Radiation stents can be fabricated by the dental oncologist under the direction of the radiation oncologist. These intraoral devices can position oral tissues into or away from the radiation treatment fields and help to immobilize the oral cavity structures

during each daily treatment.36 Two common stents are the mouth opening/tongue depressing (MOTD) stent, and the unilateral stent. The MOTD stent separates the maxilla and the mandible by approximately 2 cm. and depresses the tongue into the floor of the mouth. This stent spares the mandible and tongue if the maxillary sinus/nasal cavity structure is being radiated. Conversely, the MOTD stent spares the maxillary sinus/nasal cavity structures if the tongue, mandible, or neck is being radiated. The unilateral stent is utilized during radiotherapy treatment of lateralized malignancies, that is, parotid, buccal mucosa, tonsil, retromolar trigone. This stent positions the tongue to the unaffected side, and positions the maxilla and the mandible in the same position during each treatment (Fig. 9-16).

during each daily treatment.36 Two common stents are the mouth opening/tongue depressing (MOTD) stent, and the unilateral stent. The MOTD stent separates the maxilla and the mandible by approximately 2 cm. and depresses the tongue into the floor of the mouth. This stent spares the mandible and tongue if the maxillary sinus/nasal cavity structure is being radiated. Conversely, the MOTD stent spares the maxillary sinus/nasal cavity structures if the tongue, mandible, or neck is being radiated. The unilateral stent is utilized during radiotherapy treatment of lateralized malignancies, that is, parotid, buccal mucosa, tonsil, retromolar trigone. This stent positions the tongue to the unaffected side, and positions the maxilla and the mandible in the same position during each treatment (Fig. 9-16).

FIGURE 9-15. Nasal defect that represents basic principles for surgical preparation of facial defects. A split-thickness skin graft reconstruction that stabilizes the borders of the defect and no tissue tags is shown. The superior rim and tragus should be spared if possible when dealing with ear defects.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|