Figure 8.1 An odontogenic infection can express itself after erosion through jaw bone, depending on the thickness of the overlying bone and the nature of the surrounding soft tissues. This illustration displays six possible locations: (1) vestibular abscess, (2) buccal space, (3) palatal abscess, (4) sublingual space, (5) submandibular space, and (6) maxillary sinus. Cummings: Otolaryngology: Head & Neck Surgery, 4th ed., Copyright © 2005 Mosby, Inc.

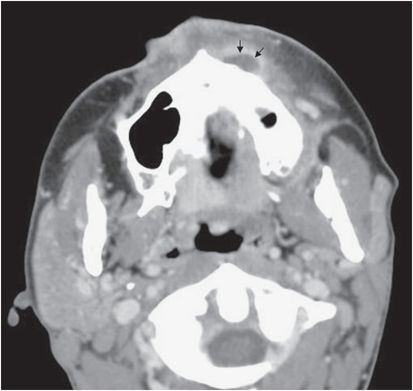

Figure 8.2 CT image demonstrating an abscess of the canine space (black arrows).

In the mandible, the thinnest region is on the lingual aspect around the molars and the buccal aspect anteriorly. The primary mandibular spaces include the submental, sublingual, and submandibular fascial spaces. The submental space is that area between the anterior belly of the digastric muscle, the mylohyoid muscle, and the skin. Infection here usually results from the mandibular incisors (Figure 8.3). Medially, the sublingual and submandibular spaces are typically affected by the mandibular molars. Whether the infection is in the sublingual or submandibular space is determined by the relationship between the area of perforation and the mylohyoid attachment. Specifically, if the apex of the offending tooth is superior to that of the mylohyoid (e.g., premolars, first molar, and occasionally second molar), the sublingual space is affected; if the infection is inferior (e.g., third molar and occasionally second molar), the submandibular space is involved. Multiple fascial spaces can be infected simultaneously. For example, the sublingual space lies between the oral mucosa and the mylohyoid and communicates along the posterior boundary of the mylohyoid muscle with the submandibular space. When infection involves the primary mandibular spaces bilaterally it is known as Ludwig’s angina.

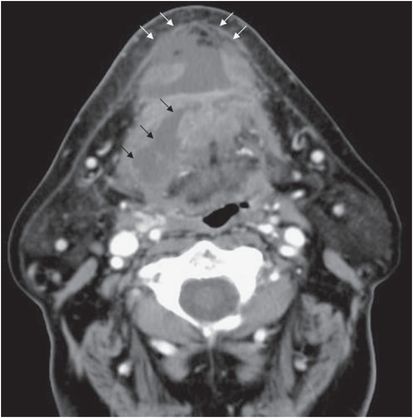

Figure 8.3 CT image demonstrating an abscess of the floor of mouth (black arrows) and submental space (white arrows).

Odontogenic infection can extend beyond the mandibular spaces to the neck to involve the cervical fascial spaces. The secondary mandibular spaces include the pterygomandibular, masseteric, and temporal spaces. These fascial spaces become infected as the result of secondary spread from more anterior spaces, including the buccal, sublingual, and submandibular spaces. The pterygomandibular space lies between the medial aspect of the mandible and the medial pterygoid muscle. The masseteric space is that area between the lateral mandible and the masseter muscle, and the temporal space is superior and posterior to the pterygomandibular and masseteric spaces. Infection of these areas almost uniformly produces trismus resulting from inflammation of the muscles of mastication.

Infection in these spaces may progress to the deep neck spaces, which include the lateral pharyngeal (parapharyngeal) space, the retropharyngeal space, and the prevertebral space. Infections of these spaces are discussed in detail in Chapter 10, Deep neck infections. One should keep in mind, however, that up to 30% of deep neck infections may result from odontogenic processes. Deep neck infections may spread distally into the mediastinum.

Pathophysiology

Odontogenic infections and their complications may be encountered by any clinician who treats diseases of the mouth and throat. Most infections are minor and self-limited, confined to the offending tooth and its apex. Under certain circumstances, however, the infectious process may break through the bony, muscular, fascial, and mucosal barriers and spread to contiguous spaces, resulting in soft-tissue infections.

Typically, infections originate within the dental pulp, periodontal tissue, or pericoronal tissue from a carious tooth. This results in bacterial invasion and a local inflammatory response, which includes vasodilatation and edema leading to increased pressure, which exacerbates the pain and decreases the blood supply. This sequence of events exacerbates the periapical necrosis, with subsequent bacterial invasion into bone and erosion of the bony cortex into surrounding soft tissues. The spreading infection can result in a chronic sinus tract or, under the appropriate circumstances (e.g., perforation of the cortical bone above the muscular attachment), a fascial space collection. Alternatively, infections involving the maxillary dentition may spread to involve the maxillary sinus and present as unilateral maxillary sinusitis.

The microbiology of odontogenic infection reflects the normal endogenous oral flora. A large number of bacteria are contained in the mouth, particularly around the dental crevices. It has been estimated that 40% to 70% of all oral bacterial species have yet to be cultivated and phenotypically characterized. Infections that result from the spread of these organisms into surrounding soft-tissue spaces are often polymicrobial. Anaerobic bacteria are dominant in odontogenic infections. Techniques for isolating and identifying anaerobic bacteria tend to be labor- and time-intensive. Molecular biology techniques including PCR and pyrosequencing have enhanced our understanding of the microbiology of the oral flora and odontogenic infections.

The phyla Firmicutes (e.g., genera Streptococcus, Dialister, Filifactor, and Pseudoramibacter) and Bacteroidetes (e.g., genera Porphyromonas, Prevotella, and Tannerella) comprise more than 70% of the species found in dental abscesses. Other species frequently identified belong to the phyla Fusobacteria (e.g., genera Fusobacterium and Leptotrichia), Actinobacteria (e.g., genera Actinomyces and Propionibacterium), Spirochaetes (e.g., genus Treponema), Synergistetes

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree