Defining Constipation

Constipation most classically refers to reduced defecation frequency and hard stools. Physicians typically define constipation as less than three bowel movements per week. Patients more frequently describe constipation as defecatory difficulty with predominant complaints of straining or hard stools. This holds particularly true in older adults. Understanding the patient’s view of ‘constipation’ assists in the evaluation and treatment process.

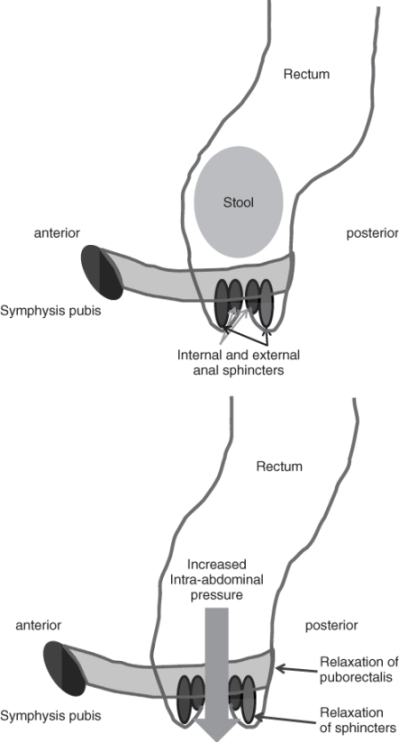

The normal defecatory process requires sufficient cognition recognizing the need to defecate, normal colon transit and normal pelvic floor function. Normal colon transit ranges from 24 to 72 h. Defecation is most often preceded by high-amplitude propagated colonic contractions. These colonic contractions occur in response to meals, particularly those with higher concentrations of calories and fat. Colonic motility is also more robust during waking hours and quiescent at sleep. Once stool is delivered to the rectum, defecation may be voluntarily initiated through a set of coordinated actions. First the stool bolus must be sensed through local sensory neurons and recognized centrally. Initiation of the defecation may follow with relaxation of the puborectalis muscle, opening of the anorectal angle and relaxation of the anal sphincters and accompanied by a simultaneous rise in intra-abdominal pressure (Figure 25.1). An abnormality affecting any of these areas results in the development of an altered bowel pattern (Table 25.1).

Table 25.1 Anatomical distribution of changes associated with constipation.

| Central nervous system |

| Awareness of need to defecate |

| Cerebrovascular accident |

| Dementia |

| Peripheral nervous system |

| Controls myogenic activity of puborectalis |

| Pudendal nerve injury |

| Enteric nervous system |

| Controls rectal sensory function, peristalsis and internal anal sphincter |

| Parkinson’s disease |

| Desensitization (chronically distended rectum) |

| Diabetes mellitus |

| Skeletal muscle |

| Contraction/relaxation of puborectalis and external sphincter |

| Direct muscular damage (e.g. prior birth trauma, sphincterotomy) |

| Rheumatological disorders (e.g. scleroderma, reduced muscular strength) |

| Incoordination |

| Idiopathic |

| Parkinson’s disease |

| Cerebrovascular accident |

Constipation may be defined in many different ways. Simply stated, primary constipation refers to constipation without an obvious cause and secondary constipation results from external aetiologies. These external causes of altered bowel function may include neuromuscular disorders, metabolic abnormalities, medications, insufficient diet or mechanical factors obstructing the movement of stool. Constipation may be further defined as acute or chronic. Chronic constipation indicates that symptoms have been present for more than 3 months and typically dates back years. Acute constipation requires a more rapid investigation into the aetiology, including evaluation for structural abnormalities or recent medication changes. Patients with chronic constipation may initially be treated symptomatically with fibre and/or simple laxatives. Those not responding to usual treatments require further investigation to evaluate for evidence of slow transit constipation or dyssynergic defecation (also called pelvic outlet dysfunction). Although constipation commonly occurs in the setting of the irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), new-onset IBS occurs less frequently in older than in younger patients. Specific criteria have been defined for identifying constipation by different investigators. The most commonly used are the Rome criteria, now in their third iteration, a classification used primarily for the purpose of clinical trials.1

Epidemiology, Pathophysiology and Impact

Constipation has long been misunderstood as a common problem associated with ageing. The prevalence of self-reported constipation, physician visits and laxative use increases with ageing.2–4 In contrast, reported stool frequency does not change with age.2, 3 Challenges in defining the prevalence of constipation in elders relates to the variety of criteria used in different studies. Self-reported constipation affects 27% of individuals aged 65 years and older, whereas only 17% of elders meet more stringent (e.g. Rome criteria) diagnostic criteria for constipation.5 When adjusting for race and laxative use, odds ratios for less than three bowel movements per week in individuals aged 70–79 and ≥80 years were 0.61 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.51–0.72] and 0.85 (95% CI, 0.68–1.03), respectively, compared with individuals <40 years of age.2 Thus, age alone is not an independent risk factor for reduced stool frequency. Likewise, little evidence exists to support low-fibre diets, lack of fluid or reduced exercise as contributing to constipation in the otherwise healthy older patient.6, 7 Women report fewer bowel movements per week than do men. Non-whites and individuals of lower socioeconomic status report fewer stools.8 In frail elders, up to 45% report constipation as a health concern.9 The prevalence of constipation is higher in nursing home residents, a finding partially explained by the use of constipating medications.10 Nursing home residents frequently (58%) use laxatives, usually on an as-needed basis.11 In older persons, the development of constipation typically represents the effects of medications and/or comorbid disease. The traditional perception of constipation as a result of ageing no longer holds; the healthy older person is not predestined to develop constipation.

Elders reporting constipation more often describe straining and hard bowel movements than reduced stool frequency.2, 12, 13 Population-based prevalence of constipation includes 40% of community-dwelling adults over the age of 64 years.14 The risk factor most commonly reported for constipation is medication use, including non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).14

Despite the lack of difference in risk factor-adjusted constipation rates between elders and younger individuals, elders more frequently use laxatives. Up to 50% of elderly women reporting use laxatives. Overall, 20–30% of community-dwelling elders use laxatives on at least a weekly basis. In nursing homes, 58% of residents receive laxatives on at least an intermittent basis.11 Few economic studies in the USA have outlined the costs of laxative use by elders. Annual estimated healthcare costs using an administrative claims database (excluding out-of-pocket costs) were $7522 per person (average age 52 years) at one health maintenance organization.15 Most elders self-treat with over-the-counter products; hence the economic impact of laxative use is probably considerably higher than this estimate.

The findings of similar stool frequency but increased defecatory difficulty parallel the reported physiological changes that occur in the digestive tract with ageing. Colon transit overall is generally well preserved with ageing in humans.16 Changes in pelvic floor function may contribute to defecatory difficulty, with older women demonstrating reduced opening of the anorectal angle and a greater degree of perineal descent compared with younger women.17 Pudendal neuropathy also occurs more commonly with ageing and may negatively affect pelvic floor function.18 Other factors correlated with constipation in ageing include reduced caloric intake, use of multiple medications, haemorrhoids and pain in the abdomen.19, 20 Many diseases that occur more commonly in elders also contribute to the development of constipation, such as diabetes mellitus, Parkinson’s disease and stroke.21–23 Prior surgery may also affect bowel function in elders. In women over 50 years of age, hysterectomy results in prolonged colon transit time and greater complaints of constipation and straining than in controls.24 Since ageing alone has little influence on the development of constipation, when complaints of constipation occur in elders, it commonly relates to medical comorbidities and increased defecatory difficulty.

The consequences of constipation in elders make it a significant health problem. The presence of chronic constipation impacts functioning in daily living, and elders with these complaints rate their health lower than people without gastrointestinal symptoms.25 These findings were not confounded by the presence of other chronic illnesses or medication use. Health-related quality of life is reduced in patients with chronic constipation.26 The presence of constipation has also been hypothesized to increase urinary tract symptoms with treatment of constipation resulting in reduced urinary frequency, urgency and dysuria.27 Constipation is also associated with bowel incontinence and treatment of constipation reduces incontinence episodes.28, 29 Immobile or cognitively impaired individuals with constipation face an increased risk of faecal impaction and stercoral ulceration.28, 30 Constipation reduces quality of life and diminishes self-perceived health in community-dwelling elders.25 More effective strategies are needed for reducing the burden of illness and costs associated with constipation.

Aetiology of Constipation

Of the multiple causes of constipation in older persons, most relate to medication use or coexisting medical illness (Tables 25.2 and 25.3). The most commonly implicated medications are opiates, NSAIDs and medications with anticholinergic effects. Although immobility and reduced fluid and fibre intake are often implicated in the development of constipation, there is little evidence to support this folklore. Increased physical activity does not reliably improve constipation.31 Reduced caloric intake correlates more closely with constipation in elders than do differences in fibre intake.19 Likewise, reduced liquid intake does not appear to cause constipation in most elders.13 Increased psychological distress correlates with reports of constipation by elders, although the mechanism for this association remains unknown.13, 19

Table 25.2 Medications commonly associated with constipation.

| Anticonvulsants |

| Antidepressants (SSRIs and TCAs)a |

| Antihistamines |

| Antipsychotics |

| Bromocriptine |

| Calcium channel blockers |

| Calcium supplements |

| Diuretics |

| Ferrous gluconate and ferrous sulfate |

| Levodopa |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| Opiates |

aSSRIs, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; TCAs, tricyclic antidepressants.

Table 25.3 Medical conditions commonly associated with constipation.

| Mechanical obstruction |

| Colonic neoplasia |

| Colonic stricture (intrinsic or extrinsic) |

| Anal stenosis |

| Metabolic |

| Amyloidosis |

| Chronic kidney disease |

| Diabetes mellitus |

| Electrolyte disturbance (hypercalcaemia, hypomagnesaemia) |

| Hyperparathyroidism |

| Hypothyroidism |

| Neurological |

| Autonomic neuropathy |

| Cerebrovascular accident |

| Dementia |

| Multiple sclerosis |

| Parkinson’s disease |

| Rheumatological |

| Polymyositis |

| Scleroderma |

| Psychiatric |

| Depression |

Clinical Approach

History

The evaluation of constipation begins first with understanding the patient’s perspective on their altered bowel function and the time course of constipation development. The acute or subacute onset of constipation requires a more aggressive diagnostic approach to exclude structural lesions, including colon neoplasia, stricture and volvulus. Likewise, the presence of weight loss, rectal bleeding, history of inflammatory bowel disease, family history of colorectal neoplasia or presence of iron deficiency anaemia require a structural examination to exclude cancer or other aetiology. Additional helpful details in the patient history include onset of constipation, frequency of bowel movements, sensation of incomplete evacuation, straining to defecate, consistency of the stool, associated abdominal pain, the need for digitation, perineal splinting or unusual postures for defecation to occur, episodes of bowel incontinence, prior abdominal or pelvic surgery, prior abdominal or pelvic radiation therapy and prior pregnancies. It is also necessary to review current medications and supplements, current and previously used laxatives with their degree of effectiveness, use of enemas and use of complementary therapies to treat constipation (e.g. high colonics, herbs, teas). Dietary history includes a general survey of calories ingested, fibre intake and restricted foods. Given the consistent association of constipation with depression and anxiety, a brief psychological assessment is also warranted. In general, the ideal, evidence based approach to the diagnostic evaluation of constipation remains to be identified.

Physical Examination

The physical examination is directed to identifying underlying medical causes for constipation, excluding faecal impaction, and providing a preliminary assessment of anorectal function. A faecal mass may be palpable on abdominal palpation. Rectal examination includes inspection of the perineum at rest and with strain. Normal perineal descent during strain is 1–4 cm. No perineal descent suggests failure of the pelvic floor to relax and allow the passage of stool. Excessive perineal descent, sometimes characterized as a ballooning of the perineum, indicates excess laxity to the pelvic floor musculature and dyssynergic defecation. This finding is most common in multiparous women. The strength of the anal sphincter muscle at rest and with squeeze is assessed. Puborectalis and anal sphincter relaxation during strain provide a measure of proper of the appropriateness of pelvic floor function. Failure of relaxation or very high anal sphincter resting pressure suggests dyssynergic defecation. The presence of weak anal sphincter pressures may place the patient at risk for incontinence during treatment of the constipation. Rectal prolapse can be associated with difficult evacuation due to blockage of the anal canal with rectum. These patients usually also described episodes of bowel incontinence. A more severe rectal prolapse can be identified during strain in the left lateral decubitus position. A better way to assess for rectal prolapse is to have the patient strain over a commode. The examiner places a gloved hand below the anus and can feel the rectal prolapse descend and touch the glove. The degree of rectal prolapse can be assessed by visual inspection. The physical examination, including rectal examination. is a necessary part of the evaluation of any constipated patient.

Diagnostic Tests

Laboratory tests often recommended in the evaluation of constipation include a complete blood count, metabolic panel that includes electrolytes, creatinine, magnesium and calcium and sTSH (sensitive thyroid-stimulating hormone). Stool examination for occult blood should be assessed. The need for a colonic structural examination is dictated by the need for routine colorectal screening, presence of worrisome signs such as bleeding or anaemia or recent change in bowel habit. The yield of colonoscopy in identifying neoplasia is no different in the individual with constipation compared to what would be identified in an asymptomatic population undergoing screening. Many patients with long-standing constipation and no warning symptoms can undergo a therapeutic trial with fibre or an osmotic laxative, preserving further evaluation for those who fail to respond to simple interventions.

Patients with more severe or medication-unresponsive constipation may benefit from further evaluation, including physiological testing. It is difficult to predict the underlying pathophysiology of chronic constipation by symptoms alone.32

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree