Common Large Intestinal Disorders: Introduction

In the elderly, gastrointestinal (GI) disorders, especially those of the large intestine, account for a significant portion of physician visits, inpatient hospitalizations, and health care expenditure in the United States. Not only are large intestinal disorders common, but in the elderly their presentations, complications, and treatment may be different than in the young. This chapter focuses on diagnosis and treatment of a variety of diseases of the large intestine, including diverticular disease, Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea, microscopic colitis, inflammatory bowel disease, colonic ischemia, colonic obstruction, and lower GI bleeding.

Diagnosis of GI disorders in an elderly patient poses several additional challenges to the physician on top of those present for all patients. First, comorbid illnesses are frequent and often numerous, and some such as dementia and depression may impair adequate communication between patient and caregiver. Second, medications and their side effects may cloud the clinical picture; polypharmacy is common in the elderly. Lastly, symptoms attributable to the large intestine may be manifestations of different diseases in the elderly than they would in the young. The astute geriatrician must take these factors into consideration when treating all patients.

Diagnostic Testing

Symptoms of digestive diseases may be misinterpreted or atypical in the aged. For example, constipation may be a symptom of irritable bowel syndrome in a young patient, whereas it might herald an obstructing lesion in an older patient. Rectal bleeding in a young person is most commonly from hemorrhoids or inflammatory bowel disease. In the elderly, diverticulosis or colon cancer more commonly cause rectal bleeding. A complete and thorough history is imperative in patients, especially the elderly. Subtle clues to the diagnosis are sometimes dismissed as physiologic aspects of aging. Physical examination and some laboratory tests including tests of liver function are unaffected by aging, and any abnormality should be evaluated for the presence of a disease state and not dismissed as an age-related change (Table 92-1).

SYMPTOM | YOUNG PATIENT | ELDERLY PATIENT |

|---|---|---|

Rectal bleeding | Hemorrhoids | Diverticulosis |

Inflammatory bowel disease | Vascular ectasia | |

Colon cancer | Colonic polyp | |

Constipation | Irritable bowel syndrome | Obstructing lesion |

Anal stricture | Inflammatory bowel disease | Neoplasm |

Radiation-induced injury |

Colonoscopy in the elderly is safe and well tolerated. Several studies of indications and outcomes of patients older than 80 years having elective and emergency endoscopic procedures found those tests to be safe; advanced age is not a contraindication to endoscopy. Moreover, the yield for diagnostic testing with colonoscopy in the elderly is relatively high.

Adequate bowel preparation is critical to a successful colonoscopic examination. Bowel cleansing in the elderly should be performed with care. Preparation with standard doses of polyethylene glycol based lavage solutions (PEG-ELS) in the elderly is well tolerated and produces satisfactory bowel cleansing in more than 95% of all cases. Sodium phosphate osmotic laxative preparation may also be used for bowel preparation, but causes significant fluid shifts and may cause electrolyte abnormalities or renal failure in this subset of patients. Sodium phosphate laxatives should be used with caution in the elderly and those with kidney or heart disease.

Most colonoscopies are performed under conscious sedation. Sedation for colonoscopy usually includes a combination of a benzodiazepine (midazolam or diazepam) and a narcotic (meperidine or fentanyl), or may include a short-acting anesthetic agent such as propofol. The elderly may be more sensitive to the agents used for sedation in GI endoscopy; small incremental doses should be given and the patient monitored closely for signs of cardiopulmonary compromise. Nevertheless, age alone is not a major determinant of morbidity; rapid or excessive dosing contributes more to complications from sedation than does age itself.

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) can be used to diagnose and manage disease of the anorectum. EUS utilizes high frequency ultrasound waves emitted from a probe attached to an endoscope to delineate the layers of the rectal wall, the internal and external anal sphincters, and the pelvic floor muscles. EUS may be helpful in evaluating these structures in patients with fecal incontinence. EUS also is frequently used to stage rectal malignancy, providing information about the depth of tumor invasion and the status of regional lymph nodes. Direct tissue sampling is available through fine needle aspiration at the time of the EUS.

Contrast studies of the large intestine involve coating the colonic mucosa with a contrast medium, usually barium sulfate, following thorough colonic preparation. Barium enemas may be performed by either single- or double-contrast method; in the latter, air is insufflated as well as barium. The single-contrast technique often is used to diagnose colonic strictures, fistula, obstruction, or diverticulitis. Double-contrast barium enema more commonly is used to detect polyps or mucosal abnormalities.

There exists some controversy concerning whether double-contrast barium enema is effective as a screening tool for colon cancer. Many experts consider colonoscopy to be the gold standard screening test. Colonoscopy is safe in the elderly and is widely available. However, contrast studies may be reasonable as a first-line test when colonic strictures are suspected or the presence of likely or known obstruction might make colonoscopy unsafe.

CT colonography (virtual colonoscopy) is a radiographic technique that combines helical CT and graphics software to create a three-dimensional view of the colonic lumen. This technology was developed to detect colonic polyps. In preliminary trials of CT colonography, detection rates for polyps greater than 5 mm were similar to those for optical colonoscopy. Debate remains about the significance of finding polyps of different sizes; comparisons of CT colonography with optical colonoscopy rest on what the investigators deem to be a “significant” polyp, with much disagreement about the significance of polyps less than 5 mm. Nonetheless, CT colonography will likely play an increasingly important role in colon cancer screening in the coming years.

There are several limitations of CT colonography. First, the procedure requires formal bowel preparation, similar to that required for optical colonoscopy. Moreover, polyps and other abnormalities found at CT colonography, detected in 10% to 30% of all examinations, require conventional colonoscopy for removal. Lastly, in addition to colonic lesions, incidental extracolonic findings on CT colonography such as gall bladder, liver, and renal/adrenal abnormalities may require evaluation and possibly further invasive testing.

Diverticular Disease

Colonic diverticula are herniations of colonic mucosa through the smooth muscle layers of the colon. Strictly speaking, because colonic diverticula do not involve the muscle layer but rather are herniations of the mucosa and submucosa, they are actually pseudodiverticula. Diverticulosis has been increasingly recognized in western society and is thought to be a disorder of older individuals. Diverticula are present in approximately one-third of persons by age 50 and in approximately two-thirds by age 80. In western society, the predominance of diverticula occurs on the left side of the colon, specifically the sigmoid colon, although diverticula can occur anywhere in the colon.

There are three factors implicated in the pathogenesis of colonic diverticulosis. First, altered colonic motility results in increased luminal pressure along segments of the colon, and the resulting high-pressure areas cause out-pouchings at areas of weakness. Second, low intake of dietary fiber predisposes to diverticular disease, because low stool weights and slower stool transit times allow for relative increases in colonic intraluminal pressure. Third, with age the structural integrity of the colonic muscular wall decreases, and diverticula are more likely to form as a result.

Diverticulosis is usually an incidental finding in patients undergoing radiographic studies or colonoscopy for other reasons. There is no clear indication for therapy or follow-up in such patients. Large cohort studies suggest that complications of diverticular disease may be prevented by intake of a high-fiber diet. Although prospective, randomized studies are lacking, a diet high in fiber and low in fat appears to be reasonable, and one that likely provides other health benefits as well as potentially decreasing the risk of complications from diverticulosis.

Some patients with diverticulosis have left lower quadrant pain, and when examined, do not have evidence of inflammation. These patients may have painful diverticular disease. Pain often is described as crampy, located in the left lower abdomen, and may be associated with diarrhea or constipation as well as tenderness over the affected area. The pain is often exacerbated by eating and diminished by defecation or the passage of flatus. The symptoms of painful diverticular disease often overlap with those of irritable bowel syndrome, and therefore painful diverticular disease is considered part of the spectrum of functional bowel disorders. It is important to consider other causes of left lower quadrant pain such as diverticulitis, colonic obstruction, and incarcerated hernias in such patients.

Diverticulitis, defined as having diverticulosis in association with inflammation, infection, or both, is probably the most common clinical manifestation of diverticular disease. Diverticulitis develops in approximately 10% to 25% of individuals with diverticulosis who are followed for 10 years or more; however, less than 20% of these patients require hospitalization.

The process by which a diverticulum becomes inflamed has been compared to appendicitis, in which the diverticulum becomes obstructed by stool in its neck. The resulting obstruction eventually leads to micro- or macroperforation of the diverticulum. Fever, leukocytosis, and rebound tenderness often ensue. In an elderly patient, absence of these findings unfortunately does not rule out diverticulitis, and an aggressive evaluation is indicated if this diagnosis is suspected.

An abdominal and pelvic CT scan often confirms the diagnosis when the clinical suspicion is for diverticulitis, and the radiographic finding may or may not include evidence of a pericolic abscess. Colonoscopy or barium enema should be delayed until inflammation has improved because of an increased risk of colonic perforation with these studies. Patients with severe pain, nausea, and vomiting often require hospitalization and benefit from intravenous antibiotics. Most patients with diverticulitis will improve within 48 to 72 hours, and then a 5 to 7 day course of oral antibiotics with gradual introduction of oral intake is adequate therapy. Selected patients with relatively mild symptoms and who are able to tolerate oral intake may be managed with close outpatient monitoring including oral antibiotics and bowel rest. Given the high incidence of complicated disease, there should be a low threshold for hospitalization in elderly patients with diverticulitis.

Patients with complicated disease including those with abscesses may need drainage by surgery or interventional radiology. Surgery is recommended for patients with diverticulitis who fail to respond to medical therapy within 72 hours, those with two or more attacks, and those with one attack complicated by abscess, obstruction, or when the inflammatory process involves the bladder. The operation can usually be done in one stage with a primary bowel anastomosis. Sometimes, however, a two-stage procedure with a temporary colostomy may be necessary.

Three to five percent of patients with diverticulosis have hemorrhage from a diverticulum. Diverticular hemorrhage is the most common identifiable cause of significant lower GI bleeding, accounting for 30% to 40% of cases with confirmed sources.

Bleeding associated with diverticula is typically brisk, and painless. While the majority of diverticula are located in the left colon, bleeding from diverticular disease usually arises from the right colon. Bleeding is said to arise from arterial rupture of the vasa recta as it courses over the dome of a diverticulum. Bleeding ceases spontaneously in 70% to 80% of patients, and re-bleeding rates range from 22% to 38%. Re-bleeding is more likely when the initial bleed is severe.

The initial step in the management of patients with hemodynamically significant bleeding from diverticulosis is stabilization with intravenous fluid and blood products as necessary. Stable patients with suspected diverticular hemorrhage may undergo colonoscopy following rapid colonic purge. Colonoscopy in this setting allows for the ability to identify a diverticular source, to exclude alternative diagnoses, and to provide therapy of actively bleeding lesions.

In patients with recurrent bleeding, nuclear tagged red blood cell scans (scintigraphy) may localize the bleeding site. A positive bleeding scan may lead to angiography, which may allow for nonsurgical management of diverticular hemorrhage. Patients who require more than three units of packed red cell transfusions over 24 hours, have bleeding refractory to treatment, or are hemodynamically unstable may require surgical management. Preoperative nuclear red blood cell scans or angiography often help localize the diseased segment and allow for limited bowel resections. Blind total colectomy is rarely indicated.

Clostridium difficile Colitis

Clostridium difficile, an anaerobic gram-positive, spore forming toxigenic bacillus was first isolated in 1935. It was not until 1978 when the association between the toxin elaborated by this bacteria and antibiotic-associated psedudomembranous colitis was made. The organism is now recognized as the single most important cause of nosocomial infectious diarrhea in the United States.

The pathogenesis of C. difficile colitis involves several steps. Patients must first be exposed to antibiotics. While the most common antibiotics associated with C. difficile colitis are ampicillin, amoxicillin, cephalosporins, and clindamycin, virtually all antibiotics (including those used to treat C. difficile colitis) have been implicated in causing disease (Table 92-2).

Next, exposure to antibiotics leads to altered colonic microflora, which in turn changes the protective barrier typically present in the colon against C difficile. Colonization of the organism in the colon is then possible. C difficile infection may result in an asymptomatic carrier state, or patients may develop diarrhea and colitis. Patients with intact immune systems and an ability to mount an early antibody response to C difficile toxin usually become asymptomatic carriers of the organism. On the other hand, patients lacking sufficient ability to mount an adequate immune response develop diarrhea and colitis.

Risk factors for the development of C difficile colitis include advanced age, multiple comorbid illnesses, intensive care unit stay, use of a nasogastric tube, acid antisecretory medications, and length of hospital stay (Table 92-3).

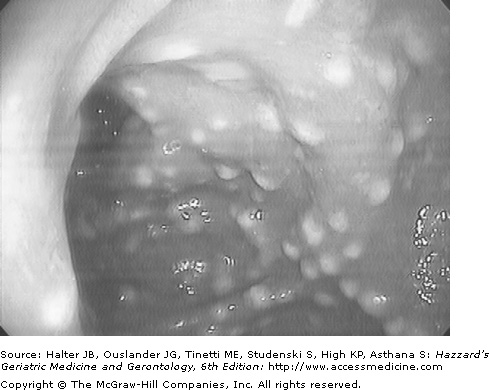

Clinical manifestations of C difficile infection range from asymptomatic carriage to mild to moderate diarrhea to life-threatening pseudomembranous colitis (Figure 92-1). Asymptomatic carriage of C difficile is common in hospitalized patients, and in fact, studies have shown that 10% to 16% of hospitalized patients receiving antibiotics are carriers of C difficile. Asymptomatic carriers should not be treated. In patients who develop diarrhea with C difficile, symptoms often develop soon after colonization. Fever, abdominal pain, and leukocytosis accompany the watery, nonbloody diarrhea. Mucus or occult blood may be present, but hematochezia should prompt an evaluation for other disease states. Patients with more severe disease may develop colonic ileus or toxic dilation without diarrhea. Abdominal radiographs will often reveal the colonic dilation.

There are several tests for diagnosing C difficile colitis. The most widely used is an enzyme linked immunoassay. This assay detects either one of the two C difficile toxins. While the main advantages are speed, cost, ease of testing, and high specificity, this immunoassay has relatively low sensitivity. Other diagnostic tests including C difficile culture, tissue culture cytotoxic assay, and PCR for detection of toxin genes are rarely used because of their high cost, need for specialized laboratory techniques, and length of time to make the diagnosis.

Colonoscopy, or more often flexible sigmoidoscopy, may be helpful in making the diagnosis of C difficile colitis but is not necessary. Endoscopy is most useful when the diagnosis is in doubt or when disease severity demands rapid diagnosis. The finding of colonic pseudomembranes in a patient with antibiotic-associated diarrhea is almost pathognomonic for C difficile colitis (Figure 92-2).

Therapy for C difficile colitis begins with withdrawal of the precipitating antibiotics if possible. Metronidazole and vancomycin are both effective in the treatment of C difficile-associated disease. (Note that the only FDA-approved drug for treating C difficile colitis in the United States is vancomycin). Metronidazole is by far less expensive, and the use of vancomycin carries with it a concern for the induction of vancomycin-resistant enterococci; therefore, the usual initial therapy is with a 10 to 14 day course of oral metronidazole. This is effective in treating the majority of patients. In patients who are too ill or cannot take oral medication, IV metronidazole can be substituted. Patients who do not respond to metronidazole can be switched to oral vancomycin. Because intravenous vancomycin does not penetrate the colonic lumen, this formulation is not effective in treating C difficile colitis. Probiotic agents such as Lactobacillus GG and Saccharomyces boulardii have been used to reconstitute the colonic microflora, and are occasionally added to metronidazole or vancomycin to treat C difficile colitis, but their effectiveness has not been demonstrated in well-designed trials.

Unfortunately, recurrent C difficile infection is a common problem and particularly prevalent in older adults. Symptomatic recurrence may result from reinfection with either the same or a different strain of C difficile. Resistance to metronidazole or vancomycin is seldom if ever an important factor in recurrence. Therefore, patients with recurrent C difficile colitis generally are given another trial with the antibiotic used to treat the initial infection. In some patients, a prolonged taper of vancomycin as well as the addition of cholestyramine over many months may be needed to prevent further recurrence (Table 92-4). A variety of other strategies, including the use of some nonabsorbable antibiotics and fecal transplantation, have been used in the treatment of recurrent C difficile infection.