Colorectal cancer (CRC), the fourth most common malignancy worldwide, remains by far the first cause of liver metastases and the first liver malignancy in Western societies.1 It is estimated that about half of these patients will develop colorectal liver metastases (CLM) during the course of disease (metachronous liver metastases), whereas 15% to 25% of the patients already present CLM at the time of the diagnosis (synchronous liver metastases).2,3

Colorectal liver metastases have become a specific oncological entity since CLM are commonly confined to the liver, by contrast to other malignancies in which liver involvement is usually part of disseminated disease. Moreover, CLM is no more considered as a terminal stage since, in some patients, resection has a potential for cure.4

Synchronous metastases are more frequently observed in younger patients. French regional registry reported that 19.8% of patients younger than 55 years had concomitant CLM at diagnosis versus 11.7% of those over 75 years.2 Similar trends were noted in other large population-based studies.5,6 It is estimated that extrahepatic metastatic disease is present in about 25% of patients with synchronous CLM.

There is no consensus on the definition of metachronicity. The term “metachronous” defined CLM that become detectable on imaging after an interval time period ranging from 3 months to 1 year after the diagnosis of the primary tumor.7 Although the majority of metachronous CLM are diagnosed within the 2 years following colorectal resection, they can appear beyond 5 years of the primary tumor resection.8 The risk of developing CLM decreases with time. The main risk factor for developing metachronous CLM is lymph node involvement of the primary tumor (stage III CRC). Other pathological features found on the specimen, such as vascular invasion, perineural invasion, and immune response, are also independent factors of relapse after resection of the primary.

Noteworthy, it is now admitted that an important proportion of patients with so-called metachronous CLM in the past should have been rather considered as synchronous. Indeed, dramatic improvement of imaging over the last decades makes now possible to diagnose small lesions, previously undetectable. This misclassification has originated an underestimation of the proportion of patients with synchronous CLM.

In most cases, the diagnosis of CLM is performed in the setting of two different situations:

During the follow-up of resection of a primary colorectal tumor

At the discovery of multiple hepatic lesions in patients with no history of primary cancer

In the first situation, the diagnosis is based on clinical history and imaging studies. In the other presentation modality, as the origin of the primary governs the therapeutic project, it is recommended to identify the primary tumor by a workup including digestive endoscopy and a thoracic–abdominopelvic CT, keeping in mind that CRC is the most likely cancer. Indeed, a national Danish registry-based study1 including all patients with liver metastases at the time of the diagnosis of a cancer showed that CRC was found in 53% of the patients, whereas pancreatic, lung, and stomach cancers accounted for 14%, 13%, and 4% of the cohort, respectively. Other malignancies (breast, esophagus, kidney) were diagnosed in lower proportions.

An ultrasound-guided biopsy is indicated when no primary tumor has been identified after a complete workup or when it appears to be the easiest way to obtain a histological confirmation. In patients with resectable lesions and a history of primary CRC, percutaneous biopsy is generally not necessary, and in many cases not recommended because of the small but real procedure-related risk, including the risk of needle track seeding, which significantly impairs survival if it occurs.9

The imaging study of choice for CLM diagnosis is the multidetector computed tomography (CT). This technique offers the advantage to be largely available and can cover thorax, abdomen, and pelvis. Although a four-phase protocol is often advocated, in practice the venous phase remains the most significant timing to detect lesions.10 A study that investigated the diagnostic value of slice thickness revealed that 2.5-mm thick slices improved lesion detection compared to thicker slices.11 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) had higher sensitivity and specificity compared to CT, particularly for small lesions.12 Regarding the positron emission tomography (PET) with 18F-fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose (FDG), a meta-analysis reported that the sensitivity of FDG-PET was higher than CT or MRI,13 although its performance seems to be altered in patients previously treated by chemotherapy.14 More recently, a randomized, multicenter study from Canada showed no clear benefit of FDG-PET in the preoperative setting.15 In practice, FDG-PET is mainly used to diagnose extrahepatic disease.

The carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) is the most widely used marker in CCR. Expressed by 75% of CCR, several studies have shown that an elevation of CEA level has prognostic significance, and the American Society of Clinical Oncology recommends its use for monitoring patients with metastatic CRC.16–19 Of note, CA 19-9 may also play a role in the follow-up as CA 19-9 level was shown to correlate with progression-free survival.19

The prognosis of CLM has been extensively investigated. The evolution of selection criteria for resection over time explains the important number of different prognostic factors reported in the literature.

Age is no more considered as having an impact on long-term outcomes in patients with equal comorbidities.20 The stage (T and N) of the primary has been shown to influence the prognosis of patients with CLM, independent of other factors.21,22 Whether the localization of the primary colorectal tumor has a prognostic value remains controversial.23,24

It has been observed that an elevation of CEA higher than 200 ng/mL is associated with poor outcomes.16

Synchronous CLM are often considered to be associated with unfavorable outcomes by reflecting a more advanced disease at diagnosis.7,16,17

The number of CLM with a cutoff of more than three lesions is commonly found as a predictor of outcome.16,22 The maximal size of a lesion was also found as prognostic factors. Recent studies suggest that the usual cutoff value of 5 cm for the size17,25 may be underestimated.

The extrahepatic localization is also a major determinant of outcome. In our series,26 patients with extrahepatic disease experienced a 5-year overall survival of 28% versus 55% in patients without extrahepatic disease after resection of their hepatic metastases.

However, the resectability of the disease, mostly relying on the metastases localization (hepatocaval junction, bilobar involvement, hepatic vein, or portal pedicle) and the possibility to save 25% to 30% of nontumoral remnant liver or a ratio FLR/body weight >0.5,27 prevails more than the absolute number or size of metastases.

The completeness of tumor resection is a major determinant of prognosis. Indeed, 5-year survivors after incomplete macroscopic resection (R2) are infrequent. In case of complete resection with safe margins of resection (R0), it has been shown that the width of margins (1 to 4 mm, 5 to 9 mm, 10 mm or more) has no prognostic value.28 Also, our group has reported that a R1 resection by necessity (complete macroscopic resection without safe microscopic margins of resection because of the close contact of the tumor to vascular structures) was not associated with a lower survival despite higher rates of intrahepatic recurrence.29 Therefore, R0 resection must remain the surgical goal, and R1 resection can only be justified when R0 is technically impossible.

The morphological response to preoperative chemotherapy has also been demonstrated to dramatically impact the outcome. While progression on preoperative chemotherapy in patients with multiple CLM was found to be an independent predictor of poor outcome, suggesting that progression was a relative contraindication to resection of CLM.30 However, a recent multicentric evaluation of patients resected while progressing on chemotherapy has showed that long-term survival could be achieved in the absence of CEA levels >200 ng/mL, and when maximum tumor size is <5 cm and/or the number of metastases is <3.31

The treatment of CLM has experienced great changes over the last decades. Considered 30 years ago as a rapidly lethal condition, CLM are now managed as a “chronic” disease with an oncosurgical approach34 that associates modern and efficient systemic treatment to control and downsize the tumoral disease (even microscopic), and complex surgical procedures, eventually repeated to remove the residual tumors. We develop below the place of chemotherapy and the surgical aspects of the CLM management.

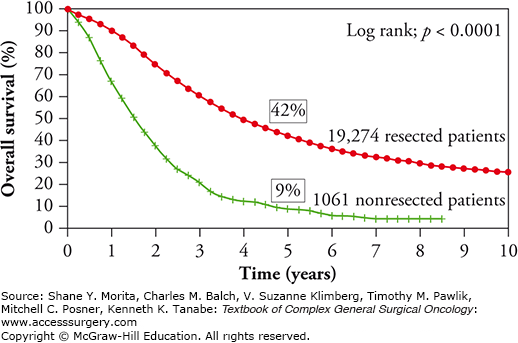

Up to the 1980s, resection of colorectal metastatic disease was anecdotal.35 In 1990, Scheele et al,36 reported a major survival advantage in patients who underwent liver resection (LR) for CLM compared to those who were offered chemotherapy alone (actuarial survival of 40% vs. no survivors after 5 years, respectively). The benefit of LR on long-term survival has been further confirmed by other single-center studies and by the international multicentric cohort of patients prospectively included in the international database Livermetsurvey with a 5- and 10-year survival of 42% and 25%, respectively (Fig. 128-1). With these results, LR is now recognized worldwide as the only potentially curative treatment of CLM, although no randomized trial comparing resection vs. systemic treatment only has even been reported.

From these data, two conclusions are suggested: patients with resectable disease should undergo resection and efforts should be undertaken to convert potentially resectable patients to resection.

Given the major importance of CLM resectability on outcome, CLM are commonly classified as upfront resectable (without the need of preoperative treatment), potentially resectable (CLM may become resectable after response to conversion chemotherapy), and definitively unresectable (no resection possible even after downsizing chemotherapy). However, owing to the increasing efficacy of chemotherapy, it is important to stress that even classified as “definitely unresectable” some patients with major unexpected morphological response can eventually been resected. This situation has led recently an expert multidisciplinary panel to propose a 2-month optimal treatment especially in patients with liver-limited disease before considering them as definitively unresectable.34

The median survival of patients without unresectable CLM has increased from 6 months with 5-FU to 24 months thanks to recent and efficient chemotherapy regimen using oxaliplatin or irinotecan. The recent development of targeted therapies (monoclonal antibodies directed against VEGF or EGFR) has contributed to increase the morphological response rate as well as the survival.37,38 This improvement in systemic therapies has enabled to render a hepatic disease initially unresectable, suitable for resection, and to decrease the risk of recurrence by controlling better the microscopic disease.39

The possibility to safely achieve a complete resection is influenced by surgical experience in liver surgery, and by the morphological response to chemotherapy; consequently , results can vary from one center to another or from one surgeon to another. The number40 and the size41 of CLM are no more absolute contraindication to resection. In fact, the decision of LR needs to meet both the oncological and technical imperatives sometimes opposed. The oncological resection relies on a complete resection of all CLM with negative margins, whereas the technical feasibility supposes to preserve a sufficient functional future remnant liver (FRL) to satisfy the metabolic demand. The international consensus42 conference on CLM defined resectability as the ability to preserve (i) two contiguous segments; (ii) adequate inflow, outflow, and biliary drainage; and (iii) sufficient FRL volume (higher than 0.5% of the body weight, 25% to 30% of the total functional liver volume). Because all the oncological strategy relies on the resectability, every patient with CLM has to be discussed in a multidisciplinary tumor board meeting including hepatic surgeons, radiologist, and medical oncologist.

The main objective of resection is to achieve a R0 resection. Most studies have shown that anatomical resections did not provide a survival advantage compared to nonanatomic resections.43,44 Therefore, when feasible, a wedge resection should be preferred as it provides equivalent oncologic results. Moreover, this strategy of “sparing parenchyma” makes rehepatectomy easier. The resection margin is no more a matter of debate. The 1-cm dogma has been challenged by reports showing that the risk of local relapse is not affected by the width of negative resection margins.28

During LR, the prevention of bleeding is a matter of concern for the surgeon as it is largely demonstrated that transfusion increases the risk of morbidity and of further relapse.45 The best mean to limit intraoperative bleeding is to perform the parenchymal transection under intermittent pedicle clamping (Pringle maneuver)46 while maintaining low caval pressure (<5 mm Hg).

The prerequisite for complete resection is the visualization of all nodules. This could be achieved by using intraoperative ultrasound,47 the performance of which could be enhanced with the use of contrast agents.48

In conclusion, hepatectomy for CLM should be undertaken after a complete exploration of the liver helped by intraoperative ultrasound and tends toward negative margin resection of all nodules, while minimizing blood loss.

The necessity of leaving sufficient remnant volume after hepatectomy has led to several surgical innovations.

First described in 1986,49 portal vein embolization (PVE) has gained worldwide acceptance as a mean to increase the volume of the FRL. The principle is to embolize the portal vein tree of the hemiliver contralateral to the FRL by using microparticles, microcoils, or biological glue. The resulting redirection of the portal flow induces an increase in the volume and of the function of the non-embolized segments. The canulation of the portal branch can be performed percutaneously under ultrasound guidance or less frequently through an ileocolic vein using a small abdominal incision. The morbidity of the procedure reported in the literature is less than 5%.50 A sufficient hypertrophy of the FRL is usually observed 3 to 4 weeks after PVE. The rate of absolute increase in the ratio FRL/total liver volume generally ranges from 6% to 10%. If the volume of FRL remains insufficient after PVE, an embolization of the ipsilateral hepatic vein has been shown to increase the hypertrophy of the FRL.51 Although PVE is an efficient and safe technique, its main drawback remains the risk of tumor growth progression of undetectable CLM located in the FRL, a situation frequently encountered in patients with multiples bilobar CLM.52

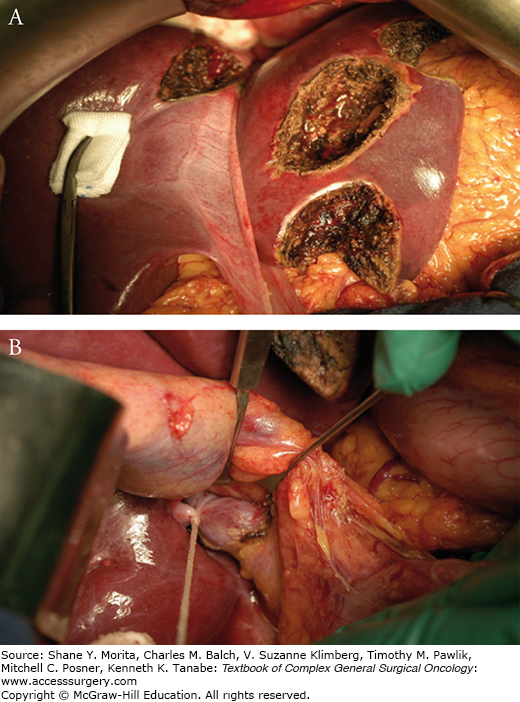

In patients with multiple bilobar CLM unresectable in a single procedure because of a too small liver remnant, a two-step strategy has been proposed to overcome this latter issue.53 The first step (Fig. 128-2) consists in the tumor clearance of the FRL associated with a ligation of the portal vein branch of the contralateral hemiliver. After an interval of several weeks, necessary to allow sufficient hypertrophy of the FRL, the contralateral liver is removed (second step). The hemiliver (right or left) exhibiting the least tumor involvement is chosen to become the FRL. Overall survival of patients who succeed to complete the two steps is close to that of patients treated in one stage. However, this strategy is impaired by the risk of not completing the two stages. Indeed, in our experience, about one-third of patients never underwent the second hepatectomy because of tumor progression occurring in interval between the two stages.54

The presence of a deep-located metastasis in the FRL raises another issue as its surgical removal may compromise the volume of FRL. To overcome this problem, often encountered in patients with multiple bilobar CLM, the use of intraoperative or percutaneous radiofrequency ablation (RFA) has been proposed. The principle of RFA is based on the heat generated from high-frequency alternating current. RFA is performed under ultrasound guidance.55 Its efficiency relies on three main principles: (i) a maximum size of tumor less than 3 cm (otherwise, the risk of local relapse exponentially increases); (ii) good visualization by ultrasound (which can be impaired in steatotic liver); (iii) a location at distance from the biliary convergence (risk of iatrogenic biliary stenosis) and from major vessels (decrease the effect if RFA by cooling).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree