Coccidioides was originally described as noted above as one species, C. immitis. More recently, two genetically distinct populations of Coccidioides have been described, C. immitis and Coccidioides posadasii, correlating to separate endemic regions. Currently, the C. immitis is maintained as the name of those isolates that are predominately found in California. The new species, C. posadasii, is predominately found in Texas, Mexico, Central America, and South America. Both species are found in Arizona [13]. Coccidioides of both species, however, show few phenotypic differences and are mycologically and clinically indistinguishable. Coccidioides is a thermal dimorphic fungus that exists either as a mycelium or a spherule. The fungus is found as far north as the northern Central Valley in California and as far south as Argentina, the place of its original description. The fungus grows in conditions where the soil has a relatively high salinity, and in a climate that has mild winters with few freezes and hot dry summers [14]. Under these ideal conditions, the fungus grows in isolated pockets as a mycelium by apical extension. These mycelia produce specialized aerial hyphae that segment and form arthroconidia. The connecting links between arthroconidia are quite fragile and separate easily with minimal mechanical force or air turbulence. The arthroconidia become airborne in a form capable of deposition in the lungs if inhaled, and can travel substantial distances, perhaps as far as 75 miles or more. These arthroconidia, if they find an appropriate soil niche, can reestablish the saprophytic phase. However, if they are inhaled by an appropriate host, they undergo transformation from arthroconidia into spherules. Spherules reproduce by endosporulation, a process whereby the growing spherule is subdivided into numerous subcompartments, each of which becomes viable daughter cells or endospores. The spherule eventually ruptures, releasing endospores, each of which may continue to propagate in tissue or revert to mycelial growth in soil or on growth media (Fig. 17.1).

Fig. 17.1

Life cycle of Coccidioides immitis depicting saprophytic (soil) and parasitic (host) phases

Epidemiology

The disease was first described in Argentina, but other foci of infection in South America and Central America also exist. Coccidioides species are found solely in the Western Hemisphere, in the “lower Sonoran life zone” [15]. The majority of the soils which support the organism are found in North America, particularly in the southwestern USA and northwestern Mexico. The areas of greatest endemicity are in the southern San Joaquin Valley and South central Arizona. The disease extends to the northern Central Valley in California and as far as Utah in the Great Plains [16]. Recently, three isolates from clinical cases have been identified in Washington State. [17]. The total number of infections per year is not known, but prevalence surveys in the 1950s of school-age children in California’s Central Valley suggested an annual risk of infection of 15 %. More recent estimates from California and Arizona have indicated that the risk has declined to 3 % or less [18, 19]. It has been estimated that in the USA there are approximately 100,000 infections annually [20]. Between 1998 and 2011, a total of 111,717 cases were reported. There has been a recent substantial increase in incidence of reported coccidioidomycosis from 5.3 per 100,000 population in the endemic area (Arizona, California, Nevada, New Mexico, and Utah) in 1998 to 42.6 per 100,000 in 2011 [21]. This increase is believed to be due to improved awareness, changes in demographics, and environmental factors [25]. Regions in which coccidioidomycosis is endemic have experienced a tremendous increase in their population. In 2005, it was estimated the populations of southern Arizona and Southern California increased by greater than 7 million inhabitants. Additionally, there is greater recognition of the disease in patients with compromised cellular immunity and in the elderly, who are more likely to have more severe disease. It appears, however, that the absolute incidence of disease has also increased, particularly during the epidemics described in the 1990s and in the first 2 years of the new millennium [22–25]. Despite the significant escalation in incidence, mortality associated with coccidioidomycosis has remained similar [26, 27].

Pathogenesis and Immunology

Virtually, all infections result from inhalation of arthroconidia. Inhaled arthroconidia transform into spherules, an inflammatory response ensues, and a local pulmonary lesion develops. In some infections, the Coccidioides species gain access to the vascular space, leaving the lungs and disseminating to other parts of the body. Control of coccidioidomycosis is predominantly cell mediated, with more severe infections seen in T-cell-deficient patients [28–30]. Additionally, in vitro observations have shown that innate cellular responses, mediated by mononuclear cells or natural killer cells, may slow fungal proliferation after infection [31]. It is conceivable that interleukin (IL)-12, IL-23, and interferon gamma may play an important role in protective immunity in coccidioidomycosis as recently demonstrated in paracoccidioidomycosis and histoplasmosis [32, 33]. Progressive and disseminated forms of coccidioidomycosis were recently described in cases with interferon gamma receptor 1 deficiency or mutation in the beta 1 subunit of the IL-12 receptor [34, 35].

Clinical Manifestations

Pulmonary

Coccidioidomycosis most commonly presents as primary pulmonary disease. The first symptoms of primary infection usually appear 7–21 days after exposure, although infection is asymptomatic 60 % of the time. In those patients presenting with symptomatic disease, the majority present with an influenza-like syndrome. Of the 40 % of total infections with symptoms, only one out of four is diagnosed; the majority of these present with pneumonic or pleural disease. There are a number of pulmonary complications of primary coccidioidomycosis. The most common is severe and persistent pneumonia. This is defined as radiographic and clinical findings of pneumonic disease for greater than 6 weeks. Progressive primary coccidioidomycosis is a syndrome described in which the patient has resolution of their pulmonary parenchymal disease with persistence of hilar and mediastinal lymphadenitis. Rare cases of progressive fibrocavitary coccidioidomycosis, which often resembles pulmonary tuberculosis, are described. Solitary thin-walled pulmonary cavities are a frequent complication (see Fig. 6.11, Chap. 6). Residual nodules are often confused with a neoplasm, particularly when individuals with unrecognized primary coccidioidomycosis present with a residual nodule on routine chest radiograph long after the time of infection [36]. Modest amounts of pleural fibrosis, a residual of the primary infection, may also be seen. Cavitary disease may rupture into the pleural space causing coccidioidal empyema, not to be confused with simple pleural effusions which may occur as part of the primary disease process. Symptoms prevalent in primary coccidioidomycosis include fever (76 %), cough (73 %), chest pain (44 %), fatigue (38 %), erythema nodosum (26 %), myalgias (23 %), shortness of breath (22 %), sputum production (22 %), chills (21 %), headache (21 %), night sweats (21 %), and other rashes (14 %) [37]. Radiographic findings in primary coccidioidomycosis typically include infiltrate only (70 %), infiltrate with hilar adenopathy (10 %), or infiltrate with effusion (10 %; Figs. 17.2, 17.3, 17.4, 17.5). Lung cavities are present in about 8 % of adults, but are less common in children. Approximately, 10 % of individuals will have a negative chest radiograph at diagnosis. Skin manifestations develop as part of the primary illness, most often as a transient non-pruritic fine papular rash. Erythema nodosum is fairly common in primary coccidioidal infection, with a strong predilection for women (Fig. 17.6). Less commonly, erythema multiforme and erythema sweetobullosum are seen [38, 39]. Migratory arthralgias are common; the triad of fever, erythema nodosum, and arthralgias has been referred to as “desert rheumatism.” Rarely, pulmonary coccidioidomycosis may present as a bronchial mass found on bronchoscopy. Chronic fibrocavitary pneumonia can occur, commonly in association with diabetes or preexisting pulmonary fibrosis [40]. Miliary disease with coccidioidomycosis is seen with significant frequency in the endemic area, where miliary coccidioidomycosis may be 10 times as frequent as miliary tuberculosis. Overwhelming miliary and/or alveolar coccidioidomycosis can result in respiratory failure. HIV-infected patients often have a fulminant presentation, particularly when CD4+ T lymphocyte counts are less than 100 cells/µl. Probably, the most common cause of death in the endemic area from coccidioidomycosis is respiratory failure, although most coccidioidal respiratory infections resolve within several weeks to months without complications.

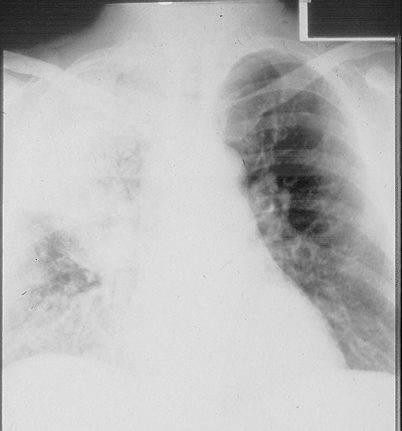

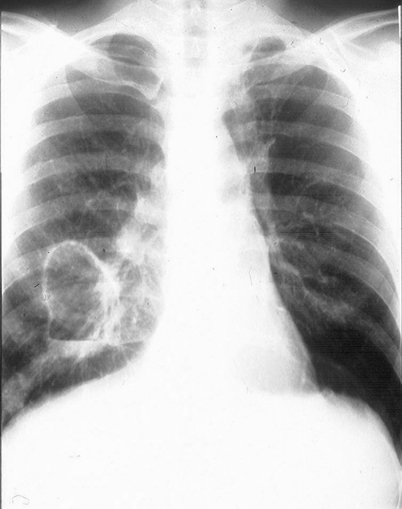

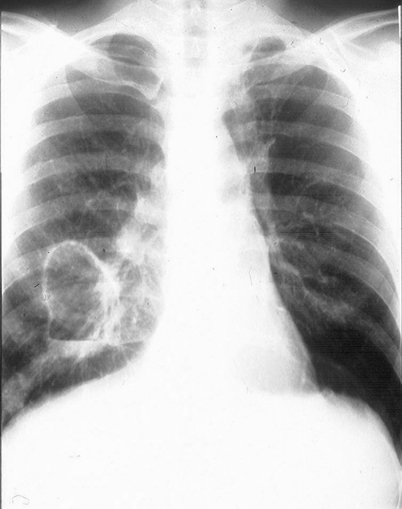

Fig. 17.2

Right upper lobe dense consolidation with associated right hilar adenopathy

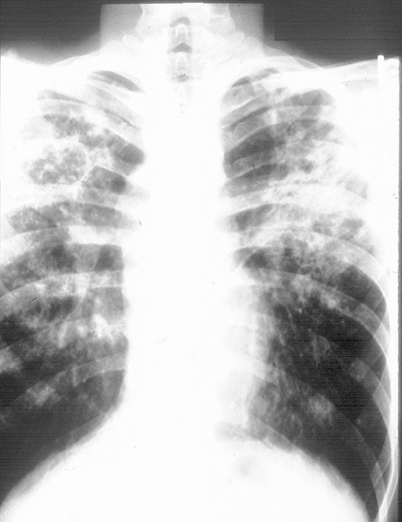

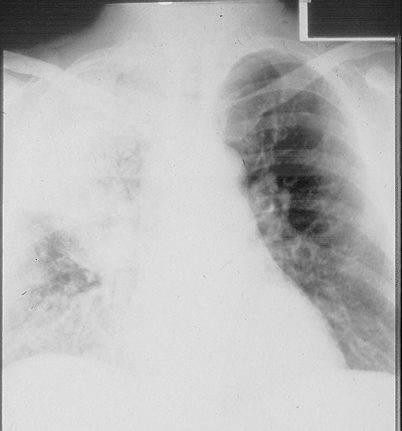

Fig. 17.3

Fibrocavitary changes involving both upper lobes. Right upper lobe cavity with air fluid level

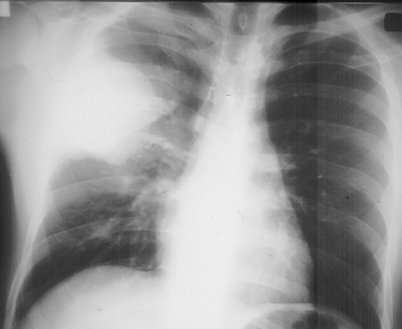

Fig. 17.4

Right upper lobe pleural-based mass with surrounding infiltrate

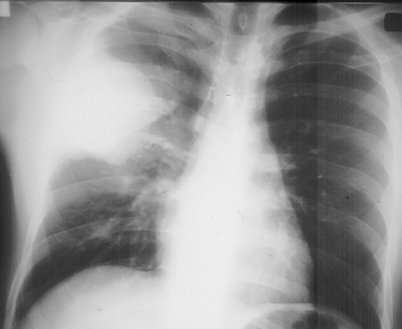

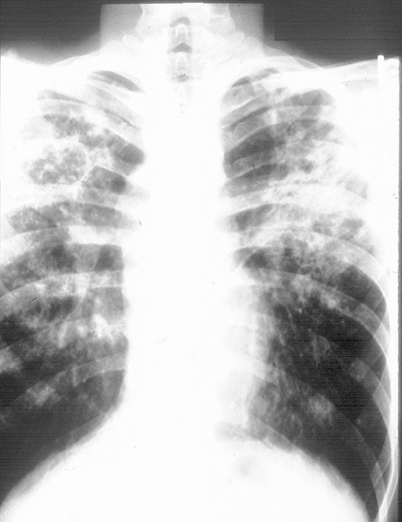

Fig. 17.5

Right middle lobe giant cavity with air fluid level and associated infiltrate

Fig. 17.6

Erythema nodosum affecting the lower extremities

Disseminated Disease

The rate of dissemination of coccidioidomycosis is highly dependent on the infected host. The majority of disseminated disease occurs in individuals with antecedent symptomatic pulmonary infection. However, in a minority of patients, disseminated disease presents without obvious primary pulmonary infection. Risk factors for dissemination include the extremes of age, male sex, African-American or Filipino ancestry, tobacco smoking, and low socioeconomic status [41, 42]. Persons with immunodeficiency, including those seen with advanced HIV infection, high-dose corticosteroid therapy, lymphoma, solid organ, or bone marrow transplantation, are at greater risk of dissemination [43–48]. Pregnancy also predisposes to individuals to disseminated disease [49, 50]. The majority of dissemination is to skin, subcutaneous tissue, bone, and joints. These sites taken together represent more than 50 % of disseminated disease. Unfortunately, the single commonest site of dissemination is the meninges. Cutaneous dissemination has a variable clinical appearance; perhaps the most characteristic is one or more verrucous lesions, which may vary in size from a few millimeters to a few centimeters (Fig. 17.7). Subcutaneous tissue infection, which usually presents as a cold abscess, is also seen with some frequency. Infections of virtually all joints have been described. Infections of the knee, elbow, wrist, and ankle are commonly seen, with the knee most frequently involved [51–53]. Dissemination similarly has been described in almost every bone. Particularly common are infections of the axial skeleton, the pelvic bones, tibia, and femur. It is not unusual to see osteomyelitis and joint involvement in the same patient. Single bone or joint infections are most common, but multiple sites may be involved, particularly in African-American males. The most severe disseminated manifestation of coccidioidomycosis is meningitis. This is the single most common dissemination site in Caucasian and Latino males. Untreated, meningitis is fatal within a few months, although there are rare reports of survival for 2 or more years [54]. Meningitis usually develops within 6 months of the initial infection [55]. The cerebrospinal fluid has an elevated white blood cell count and protein, with depressed glucose. Eosinophils are not common, but when present, they are highly suggestive of the diagnosis of coccidioidal meningitis [56]. Finally, Coccidioides may disseminate to virtually any site in the body. Coccidioidal endophthalmitis, peritonitis, and prostatitis have all been described.

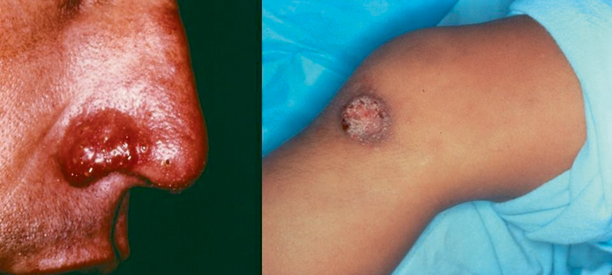

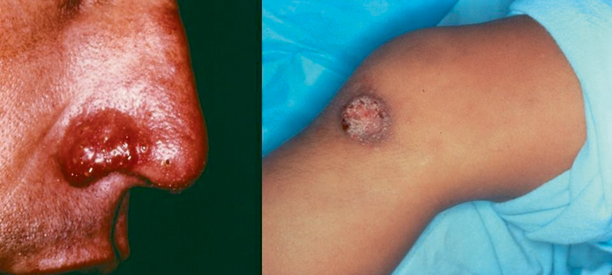

Fig. 17.7

Characteristic lesions of cutaneous coccidioidomycosis

Diagnosis

It is essential to obtain a detailed travel history for exposure to an endemic area. Exposure does not need to be over a prolonged period of time; infection has occurred after only passing through an endemic area. The diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis is dependent on a compatible clinical illness with positive laboratory confirmation by culture, histopathology, or serology.

Culture

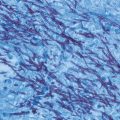

Suitable material for culture is sputum, tissue aspirates, or biopsy specimens. Coccidioides species grow well on most culture media after 5–7 days of incubation in aerobic conditions at 25, 30, or 35 °C. Typically, these fungi produce a white mold, although more pigmented strains have been observed. Laboratory cultures are highly infectious when mature arthroconidia have formed (see Fig. 2.14, Chap. 2). Typically, it takes about 10–20 days for Coccidioides to mature and produce arthroconidia. Because of their size, the arthroconidia are easily dispersed in the air and inhaled; therefore, Coccidioides is extremely hazardous when cultured in the laboratory. At a minimum, biosafety level 2 practices and facilities are recommended for handling and processing of clinical specimens. When working with known Coccidioides, biosafety level 3 is required [57]. Accidental percutaneous inoculation of the spherule form may result in local granuloma formation. Clinical specimens, prior to culture, however, are not infectious to personnel. The much larger size spherules are considerably less effective as airborne pathogens. Coccidioides will grow in most of the media, including 5 % sheep blood agar, chocolate agar, Sabouraud dextrose agar, Mycosel agar, and brain heart infusion agar with or without blood. Growth on 5 % sheep blood agar and chocolate agar incubated at 35 °C can be seen in as little as 24 h. Growth on Sabouraud dextrose agar and Mycosel agar incubated at 25 °C (room temperature) can be seen after 3–4 days. Specimens from known or suspected cases should not be cultured on unsealed plated media. Use of tubed media is suggested (Fig. 17.8). Presumptive identification may be made based on colony morphology, growth rate, and the production of alternating arthroconidia. Care must be taken when attempting to identify Coccidioides as other mycoses may have similar macroscopic and microscopic morphologies, especially if arthroconidia are not abundant (Fig. 17.9). Laboratories that are not experienced with working with Coccidioides should refer these suspected isolates to qualified reference laboratories.

Fig. 17.8

Growth of Coccidioides in tubed fungal medium

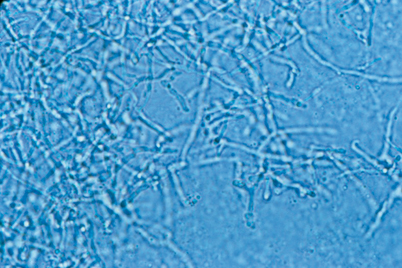

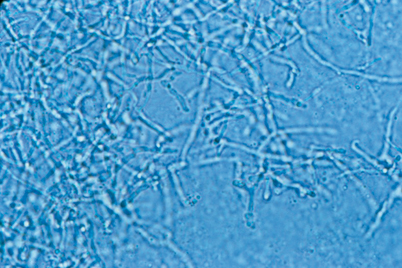

Fig. 17.9

Mycelial form of Coccidioides immitis

Coccidioides species are dimorphic fungi that have the ability to grow vegetatively at 25 °C as molds, and at 37 °C in tissue or in special medium (Converse liquid medium) in 10 % CO2 incubator as spherules. Confirmation traditionally was performed by animal inoculation with identification of endosporulating spherules on histopathology. Exoantigen tests and the production of spherules in Converse liquid medium could also be used. These methods have now been supplanted by molecular testing; a DNA probe is available commercially.

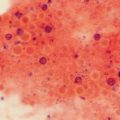

Histopathology

Serologic Testing

The most common method of diagnosis is serologic testing in individuals who have typical clinical features. Correctly performed serologic tests are both sensitive and specific for the disease. A negative serologic test, however, does not exclude the presence of infection, especially if recently acquired, and should be repeated over the course of several months. Serologic tests for Coccidioides are many. The most commonly used currently are enzyme immunoassay (EIA), immunodiffusion (ID), and complement fixation (CF) antibody tests. The EIA allows the detection of IgM antibodies for the determination of recent infection. Although this test suffers from many false positives, it is probably the most sensitive test for early infection. The ID IgM test has somewhat less sensitivity but a better specificity than the EIA test. The EIA IgG test appears to have a significant number of false negatives which limit its utility in the diagnosis of severe and advanced disease. The ID IgG test has a high degree of specificity and fewer false negatives in individuals with significant or disseminated disease. CF tests are both sensitive and specific in the diagnosis of coccidioidal infections. The quantitative CF test is expressed as a titer and has the additional advantage of being not only diagnostic but prognostic. There is an inverse relationship of the IgG antibody titer to prognosis. Individuals with decreased amounts of IgG antibodies tend to have modest primary infections. Individuals with high amounts of IgG antibodies are more likely to have extensive primary infection or disseminated disease. It must be understood, however, that this holds true for a population of patients. In a given individual, the extent and severity of disease cannot be accurately predicted solely on the measurement of IgG antibodies.

The majority of patients with disseminated disease will eventually have a titer ≥ 1:16. At present, EIA results should be confirmed with the more established ID or CF tests [58, 59]. ID and CD IgG tests will have a false negative rate of approximately 1 % in disseminated disease. The majority of individuals with disseminated disease who have falsely negative Coccidioides serology are HIV infected. The CF titer in individuals with meningitis is higher than in individuals with primary disease but lower than those with other forms of disseminated disease [60].

Skin Testing

Skin test antigens derived from both mycelia and spherules have been marketed in the past. No skin testing reagents are currently commercially available in the USA. Skin testing detects the delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to Coccidioides [61]. Since skin tests commonly remain positive for life in most people, a positive result may not be related to current illness, analogous to tuberculin skin testing. The diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis can be made by demonstrating the conversion of the skin test from negative to positive. False negative skin tests can occur in immunocompromised individuals and in the setting of overwhelming infection. Thus, a negative skin test cannot exclude a diagnosis of current or past coccidioidal infection. Skin testing therefore is limited as a screening procedure for recent infection, but may be useful in epidemiologic studies.

Other Laboratory Findings

Nonspecific laboratory tests such as the complete blood count and chemistry tests occasionally offer clues to coccidioidal infection. In an endemic area, an individual presenting with what appears to be community-acquired pneumonia who has an absolute eosinophilia (greater than 350 cells/µl) is more likely to have primary coccidioidal infection. It has also been noted that individuals who present with coccidioidomycosis and elevated alkaline phosphatase may also have liver involvement.

Radiologic Imaging

Radiographic imaging may be of great help in defining the extent and severity of both pleural pulmonary and disseminated disease. Chest radiography is mandatory in evaluation of primary disease. Computed tomography of the chest may be helpful in selected cases, especially with cavitary disease. Bone scan is the most frequently ordered test for osteomyelitis and plain radiograph is frequently utilized (see Figs. 6.13 and 6.14, Chap. 6). Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of bone and joint will help define problematic cases. MRI of the brain and spinal cord may reveal meningeal enhancement, hydrocephalus, or vasculitic infarction. Even though approximately 50 % of patients with meningitis will have normal neuroimaging ([62]; see Fig. 6.3, Chap. 6).

Treatment

General Approach

The treatment of coccidioidomycosis is both complex and, at times, controversial. A treatment guideline published by the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) in 2005 gives a consensus framework (update is in progress) [63]. It is clear that many individuals infected with Coccidioides species recover without specific therapy. This is especially true when one notes that 60 % of infections are asymptomatic and, by definition, go undiagnosed and untreated. Of symptomatic individuals, large numbers also go undiagnosed and most recover uneventfully. There is some controversy as to whether those individuals who are diagnosed with symptomatic primary disease need to be treated. Some experts believe that the majority of these persons will recover without treatment and therefore treatment ought not be offered. Other authorities note that a small but significant percentage of individuals with primary disease will have either pulmonary or disseminated complications and it is difficult to predict with certainty who these individuals might be; thus, the majority should be treated. Unfortunately, there is no evidence-based study of primary disease that has examined whether improvement in the primary symptom complex, rate of pulmonary complications, or frequency of dissemination is effected by treating or not treating. What is generally agreed upon is that individuals with significant risk factors for dissemination or poor outcome should receive treatment for primary disease (Table 17.1). Thus, advanced age; male sex; vulnerable race; presence of associated comorbid diseases such as diabetes, liver disease, and underlying lung disease; and elevated CF titers should favor treatment of primary disease. HIV infection and other conditions associated with immunodeficiency, such as lymphoma, cancer chemotherapy, and organ transplantation, mandate early and aggressive therapy of primary disease. Pregnancy represents a special circumstance. The development of primary disease during the middle trimester through the early postpartum period puts an otherwise low risk group of individuals at much higher risk. Coccidioidomycosis has been the leading cause of maternal mortality in Kern County, California, for more than 50 years [64]. Despite the risk, many women will have favorable outcomes without drug treatment, and abortions or early delivery in subjects with active infection is rare [65].

Table 17.1

Antifungal therapy of coccidioidomycosis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree