Figure 132.1 “Tennis racket” or “drumstick” appearance of Clostridum tetani. (http://www.cdc.gov/tetanus/about/photos.html)

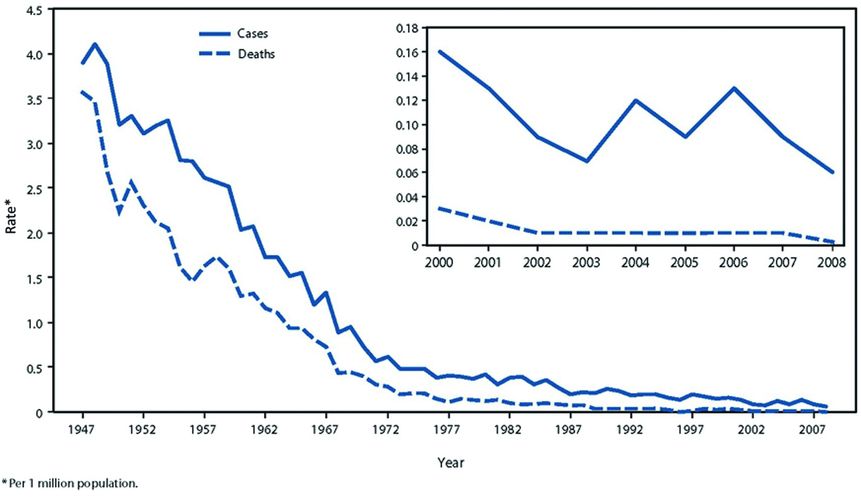

Figure 132.2 Annual rate of tetanus cases and tetanus deaths in the United States during 1947–2008, according to the National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System. From 1947–2008. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Tetanus surveillance – United States, 2001–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60 (12):365–369 available from: PM:21451446)

Pathogenesis

A wound infection with C. tetani is the first step of the disease process. Once the bacterium vegetates it produces tetanospasmin (tetanus toxin) and tetanolysin. Tetanospasmin enters the nervous system through presynaptic terminals and interrupts neuromuscular transmission whereby it can initially cause local paralysis. Once it enters the nervous system, retrograde transport facilitates its movement to the CNS where it prevents the release of inhibitory neurotransmitters, which results in an unopposed excitatory signal. This effect is also seen in the autonomic nervous system, causing a hypersympathetic state. Tetanospasmin binding is irreversible, and thus the effects last the lifetime of the neuron. The other toxin produced is tetanolysin, which causes tissue necrosis and thus a more favorable environment for growth of the bacterium.

Clinical

Tetanus exists in four clinical forms: generalized, local, cephalic, and neonatal. These forms reflect the location of initial involvement as well as the extent of disease. The incubation period is variable and can be as short as 1 day or as long as several months. The distance from the site of inoculation of the organism to the CNS is a major determinant of the incubation period, with longer distances resulting in a longer incubation period.

Generalized tetanus is the most commonly recognized form which often presents with trismus but later manifests as tonic contraction of skeletal muscles with intermittent muscular spasms. Decorticate posturing with flexion of the arms and extension of the legs is classically described with generalized spasms. There is no impairment in consciousness and thus the spasms are intensely painful. Symptoms of autonomic hyperactivity including irritability, restlessness, sweating, and tachycardia may be seen early in the course with progression to cardiac arrhythmias, labile blood pressures, and fevers in the later stages. This autonomic instability is the leading cause of death with a fatality rate of 11% to 28%.

Localized tetanus involves the muscles at the site of inoculation, presenting as tonic and spastic contractions. It may be mild and may persist for weeks to months. Although it may resolve spontaneously without long-term sequelae, it is often a prodrome of generalized tetanus. The reported incidence of localized tetanus is 13%.

Cephalic tetanus is a form of localized tetanus that involves the head or neck. Although it initially involves only the cranial nerves, it can be a prodrome of generalized tetanus. It can also spontaneously resolve without complications. The incubation period for progression to generalized tetanus is short due to its proximity to the CNS.

Neonatal tetanus typically occurs in the first 28 days of life. It develops in infants of unvaccinated mothers when infection of the umbilical stump with C. tetani occurs due to poor aseptic technique at delivery or contamination with dirt, straw, or other materials. Cultural practices involving the application of clarified butter, juices, and cow dung to the umbilical stump have also been implicated in the development of disease. It may manifest initially as general weakness and a failure to nurse but progresses to rigidity, spasms, trismus, and seizures. Sepsis, related to bacterial infection of the umbilical stump, occurs in about half of the patients and accounts for significant mortality which can exceed 90%.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of tetanus is primarily based on the typical findings mentioned above. There is no definitive testing to confirm or exclude the diagnosis. Antitetanus antibodies are often undetectable in clinical disease. Culture for C. tetani is of little value because of poor sensitivity and specificity as positive cultures may be present without disease and represent colonization rather than true infection. Inadequate immunization and inadequate wound prophylaxis are important risk factors for the development of tetanus and thus, knowing a patient’s prior vaccination status can be helpful when entertaining the diagnosis. Patients should also be questioned regarding prior tetanus prone injuries and physical exam should include evaluating for any possible inoculation sites.

There are several considerations in the differential diagnosis including drug-induced dystonia, trismus due to dental infections, strychnine poisoning, and neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Drug-induced dystonia, in contrast to tetanus, produces deviation of the eyes and an absence of tonic muscular contractions between spasms. Also, administration of anticholinergics will reverse the spasms in drug-induced dystonia but not in tetanus. Trismus due to dental infections is seen in the presence of an obvious dental abscess. Strychnine poisoning can cause a syndrome similar to tetanus. Testing of blood, urine, and tissue samples for strychnine can be done in settings when accidental or intentional poisoning is considered. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome can present with muscular rigidity and autonomic instability as well as fever and altered mental status, both of which are not seen in tetanus.

Treatment

The initial treatment of tetanus should include early and aggressive airway management. If endotracheal intubation is required,

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree