CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF CHIASMAL SYNDROMES

VISION CHANGES

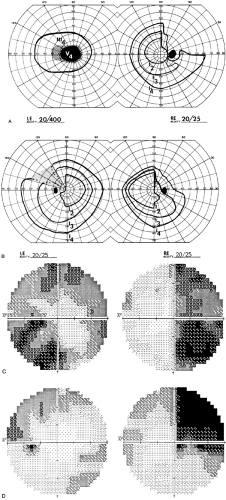

Most chiasmal syndromes are caused by extrinsic tumors: classically, pituitary adenomas or suprasellar meningiomas and craniopharyngiomas. With few exceptions, these slow-growing tumors produce insidiously progressive visual deficits in the form of variations on a bitemporal theme (Fig. 19-4). Sophisticated neuroradiologic and psychophysical testing has attempted to correlate the degree of vision loss with the degree of anatomic displacement of the chiasm10; these studies have demonstrated that vision loss occurs well before it is detectable by conventional outpatient methods of assessing visual field and visual acuity.11 Asymmetry of field loss is the rule, such that one eye may show advanced deficits, including reduced acuity, whereas only relative temporal field defects are present in the other eye. Unless acuity is diminished, patients report rather vague vision symptoms—for example, trouble seeing to the side, a history of fender accidents to their automobiles, or that, when passed by another automobile, the overtaking vehicle suddenly appears in their lane. The first clue to the presence of an hemianopic defect may be the manner in which acuity charts are read (i.e., with the right eye, only the left letters are seen, and with the left eye, only the right letters are seen). Progressive painless loss of peripheral field or central acuity (symmetric or asymmetric) may go unnoticed by many children as well as by some adults. Unilateral visual defects, especially in children, frequently are found during routine school vision tests. Rarely, vision may decrease precipitously when parachiasmal masses enlarge abruptly, as with infarction of an adenoma (“pituitary apoplexy”). Chiasmal visual field loss may differ depending on the anatomic area affected. Anterior lesions may cause an ipsilateral optic neuropathy with a contralateral superotemporal field deficit. Lesions in the body of the chiasm usually produce more symmetric bitemporal field loss, with normal visual acuity. Posterior lesions (with prefixed chiasm) may cause incongruous homonymous field loss secondary to involvement of the optic tract. Usually, many vision symptoms are vague and nonspecific until central acuity fails in one or both eyes. Unfortunately, it is all too common that visual field loss is already marked before initial perimetry is accomplished.

Vision loss of a chiasmal pattern during pregnancy should suggest the possibility of an enlargement of a preexisting pituitary adenoma or of an estrogen-dependent meningioma. There is little evidence to support the notion of a physiologic enlargement of a normal pituitary gland during pregnancy that is sufficient to encroach on the anterior visual pathways, nor is “lactation optic neuritis” a valid concept.

Even now, vision loss is the first palpable clinical manifestation of pituitary macroadenomas, but this symptom cannot be construed as an early sign. From the Mayo Clinic experience,12>40% of adenomas present as vision symptoms, and 70% show field defects.

HEADACHE

Chronic headaches, mild or severe, are noted by most patients with pituitary adenomas.13 Headache symptoms are variable but may be most marked where advancing pituitary adenomas are restrained by a taut diaphragma sellae. In acromegaly, chronic headaches may indicate paranasal sinus enlargement,

with or without active sinusitis. In children, headaches usually are not thoroughly evaluated until nausea, vomiting, and behavioral changes occur, at which point an intracranial lesion should be suspected. Additionally, obesity, precocious or delayed sexual development, somnolence, and diabetes insipidus should alert the clinician to hypothalamic dysfunction (see Chap. 9, Chap. 18 and Chap. 26).

with or without active sinusitis. In children, headaches usually are not thoroughly evaluated until nausea, vomiting, and behavioral changes occur, at which point an intracranial lesion should be suspected. Additionally, obesity, precocious or delayed sexual development, somnolence, and diabetes insipidus should alert the clinician to hypothalamic dysfunction (see Chap. 9, Chap. 18 and Chap. 26).

SENSORY PHENOMENA

Peculiar sensory phenomena may be noted by patients with bitemporal field defects, resulting in a nonparetic form of strabismus or diplopia and in difficulty with visual tasks requiring depth perception (e.g., use of a screwdriver, threading a needle, and the like). Loss of portions of normally superimposed binocular fields results in the absence of corresponding points in visual space (and on the retina) and subsequently diminished fusional capacity. In essence, the patient has two free-floating nasal hemi-fields with no interhemispheral linkage to keep them aligned. Vertical and horizontal slippage produces doubling of images, gaps in otherwise continuous visual panorama, and steps in horizontal lines. A series of 260 patients with pituitary adenoma included some degree of double vision preoperatively in 98 patients, but a demonstrable ocular palsy was present in only 14.13 Additionally, without temporal fields, objects beyond the point of binocular fixation fall on nonseeing nasal hemiretina, so that a blind area exists with extinction of objects beyond the fixation point.

EYE MOVEMENT DISORDERS

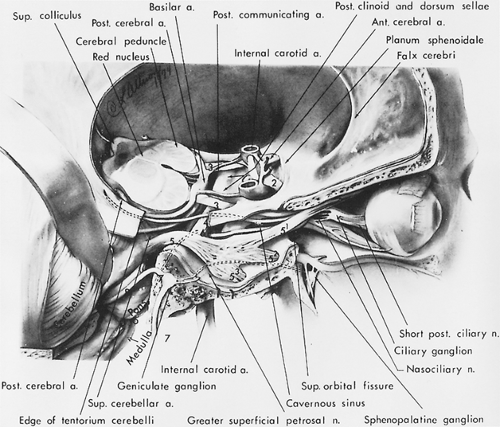

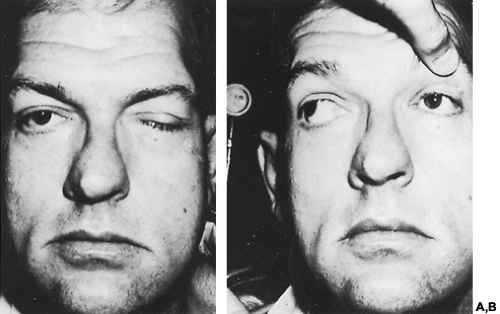

The association of extraocular muscle palsies with chiasmal field defects implies involvement of the structures in the cavernous sinus, usually a sign of rapid expansion of a pituitary adenoma. Only rarely is tumor diagnosis delayed sufficiently for obstruction of the ventricular system to occur, with elevation of intracranial pressure and unilateral or bilateral sixth nerve palsies (Fig. 19-5 and Fig. 19-6).

FIGURE 19-6. A, Acromegalic patient with involvement of left oculomotor nerve. B, Patient had reported a gradual onset of left-sided ptosis and diplopia with a mild headache. |

Patients with large parasellar masses may display “seesaw” nystagmus, with alternate depression and extorsion of one eye and elevation and intorsion of the other. This results from expansion of tumors within the third ventricle, with secondary midbrain compression, rather than from chiasmal involvement per se.14

PALLOR OF THE OPTIC DISCS

Pallor of the optic discs, although an anticipated physical sign of chiasmal interference, is not a prerequisite for diagnosis. In a series of 156 cases of pituitary tumors, optic atrophy was found in only 155 of 312 eyes (50%)15, disc pallor was present in 34% of the adenomas studied at the Mayo Clinic.12 Optic atrophy may not be

present even when vision symptoms have lasted as long as 2 years.16 Furthermore, extensive field loss in chiasmal syndromes may be associated with normal or minimally pale discs. Therefore, it is unwise to rely on the presence of optic atrophy as an indication of chiasmal interference; such findings are corroborative evidence at best, after the visual fields have been carefully evaluated.

present even when vision symptoms have lasted as long as 2 years.16 Furthermore, extensive field loss in chiasmal syndromes may be associated with normal or minimally pale discs. Therefore, it is unwise to rely on the presence of optic atrophy as an indication of chiasmal interference; such findings are corroborative evidence at best, after the visual fields have been carefully evaluated.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree