INTRODUCTION

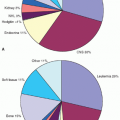

Cancer, a common disease in adults, is rare in children and adolescents (see

Chapter 1). It is often difficult to diagnose childhood cancer in its early stages because many of the presenting signs and symptoms are nonspecific and mimic common childhood diseases. Although the incidence of pediatric cancer slowly rises each year, the overall number of new cases remains small, but despite the low incidence rate, pediatric cancer remains the leading cause of disease-related mortality in children.

The challenge in diagnosing pediatric cancers is that they occur so infrequently and often initially present with symptoms of much more common and less serious illnesses (

Table 6.1). The annual incidence of cancer in children is 15 per 100,000. Therefore, the average solo practitioner is likely to encounter only one case every 20 years, and even in practices with multiple providers, one case will be diagnosed every 5 to 7 years.

1 Adding to these early detection difficulties is the fact that once a specific cancer has been diagnosed in a practice, not only will there be a long lag time until the next case presents, but the next case is likely to be an entirely different entity with different presenting features.

In spite of the inherent difficulties in diagnosis, timely diagnosis of childhood cancer is extremely important. Many pediatric malignancies are highly curable, and with some of them, earlier diagnosis can be associated with a better prognosis, diminished intensity of therapy, and less complications from disease as well as treatment.

2 Early diagnosis of pediatric cancer requires an astute physician attuned to the subtle or persistent symptoms that may herald the diagnosis of cancer. Furthermore, this increased awareness should extend to adolescents and young adults, as many of the cancers occurring in these age groups are more closely related to rare pediatric tumors than to the common malignancies seen in adults.

Consequently, it is important for pediatric oncologists to be involved in educating practitioners who see children and young adults about these diseases, so that in the appropriate context, they will see those warning signs that prompt an evaluation leading to the diagnosis of cancer. This includes educating not only pediatricians but also practitioners in family practice, emergency medicine, internal medicine, and surgery.

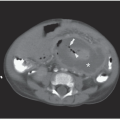

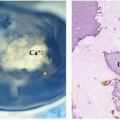

If a diagnosis of cancer is suspected or confirmed, then referral to a pediatric cancer center is critical. It is at these centers that the multidisciplinary clinical and investigative resources exist to permit the most accurate diagnosis, to offer the most appropriate therapies, and to provide the best supportive care and long-term follow-up. Diagnosing and treating childhood cancer requires a multidisciplinary team consisting of pediatric oncologists, other pediatric subspecialists, radiation oncologists, surgeons, pediatric oncology nurses, social workers, case managers, and pathologists with pediatric expertise. Ideally, the diagnostic procedures, such as biopsy and specialized imaging, should be performed at the pediatric cancer center. As the diagnosis and staging of childhood cancer continues to incorporate more biologic information and techniques, specimens require special handling and processing to permit the growing array of morphologic, histochemical, immunologic, cytogenetic, and molecular testing needed. Furthermore, these centers participate in cooperative group studies that provide for further expert review of the diagnosis as needed.

While later chapters will discuss more specific differential diagnoses for individual cancer types, this chapter focuses on some of the more common diagnostic clues to cancer in children, adolescents, and young adults with pediatric malignancies. Early signs and symptoms of cancer often suggest other disorders. As indicated previously, the occurrence of cancer in children and adolescents is relatively infrequent, and often multiple or persistent clues need to be linked together. In other cases, the diagnosis may be more straightforward, provided there is awareness that the sign or symptom points toward a diagnosis of malignancy.

CHILDREN AT RISK

Certain children are at increased risk for developing cancer. They include children with the genetic predispositions to cancer that are discussed in Chapter 2, such as Down syndrome, neurofibromatosis, and Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. Very low-birth-weight infants (<1,500 g) are at increased risk of developing hepatoblastoma.

3 Certain infectious agents may also predispose to cancer. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection has been associated with B-cell lymphomas, especially Burkitt lymphoma, as well as less common peripheral T-cell lymphomas, Hodgkin lymphoma, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, and nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

4,5,6 Hepatitis B and C infections predispose to hepatocellular carcinoma.

7,8 Infections with the human papilloma virus are the causative agent of nearly all cases of cervical cancer, and

Helicobacter pylori infections can lead to the development of gastric cancer.

9,10 Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection in pediatric patients has been associated with B-cell lymphomas, leiomyosarcomas, and Kaposi sarcoma. The latter two malignancies are otherwise not seen in children.

11 In addition to HIV, children who have inherited immunodeficiency syndromes or are on immunosuppressive therapy are at higher risk of malignancy. Posttransplant patients are prone to a posttransplant lymphoproliferative syndrome that can progress to lymphoma.

12 Pediatric solid organ transplant recipients who are on prolonged thiopurine therapy may be predisposed to myelodysplasia and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) based on adult data.

13Another group of children at increased risk for developing cancer are those who have survived therapy for another cancer.

14,15 For example, children treated for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) are at increased risk for brain tumors, especially if they received cranial radiation therapy. Survivors of ALL are also at increased risk for developing AML. Therapy that includes topoisomerase II inhibitors, anthracyclines, and alkylating agents potentiates the risk of AML, as seen in patients with solid tumors treated intensively with these agents.

16 Children with Hodgkin lymphoma treated with oncogenic agents such as procarbazine and alkylating agents are also at increased risk for secondary AML and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). Patients exposed to radiation therapy as part of their cancer treatment are at increased risk of radiation-related malignancies in the radiation-exposed field.

17 For example, this is the case in patients with Hodgkin lymphoma treated with radiation who are also at increased risk for radiation-related malignancies such as thyroid cancer, bone tumors, and early-onset breast cancer. Similarly, patients who underwent stem cell transplant are at increased risk from high-dose chemotherapy and total-body irradiation for solid tumors such as skin, bone, and thyroid cancers and from their immunosuppression for posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders.

18 Further, exposure to ionizing radiation outside of cancer therapy, either prenatally or through nuclear accidents such as Chernobyl, also increases the risk for cancer.

19