Figure 44.1 World map showing the prevalence of the chronic hepatitis B carrier state in areas of low (very light blue, <2%), medium (light blue, 2–7%), and high (dark blue, ≥8%) prevalence. (Adapted from the Centers For Disease Control and Prevention website, http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HBV/PDFs/HepBAtRisk.pdf. [Accessed April 29, 2013.])

Chronic hepatitis B may be recognized as a continuation of acute hepatitis B (Table 44.1) or as a result of repeated detection of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) in serum, often with elevated aminotransferase levels. Four phases of HBV infection are recognized (Table 44.2). In the immune tolerant phase, hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) and HBV DNA are present in serum and indicate active viral replication, but serum aminotransferase levels are normal, with little necroinflammation in the liver. This phase is common in infants and young children whose immature immune system fails to mount an immune response to HBV.

| Susceptible | Immune due to vaccination | Immune due to natural infection | Acute infection | Chronic infection | Various interpretationsa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBsAg | − | − | − | + | + | − |

| Anti-HBc | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| IgM anti-HBc | − | − | − | + | −b | − |

| HBeAg | − | − | − | + | ± | − |

| Anti-HBe | − | − | ± | − | ± | ± |

| Anti-HBs | − | + | + | − | − | − |

b IgM anti-HBc may be positive (in low titers) in some persons with chronic hepatitis B.

Anti-HBc = antibody to hepatitis B core antigen; anti-HBe = antibody to hepatitis B e antigen; anti-HBs = antibody to hepatitis B surface antigen; HBeAg = hepatitis B e antigen; HBsAg = hepatitis B surface antigen; IgM anti-HBc = IgM antibody to hepatitis B core antigen.

| Phase | ALT | HBeAg | Anti-HBe | HBV DNA (IU/mL) | Liver histology | Natural history |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immune tolerance | Normal | + | − | ≥20 000 | Minimal inflammation | Low risk of progression to advanced liver disease |

| Immune clearance | Elevated (fluctuating) | + | +/− | ≥20 000 (fluctuating) | Variable inflammation +/− fibrosis | Associated with hepatitis flares |

| Inactive carrier state | Normal | − | + | <2000 | Minimal inflammation and liver damage | Low risk of advanced liver disease HBsAg loss in 1% per year; 10–20% have reactivation of HBV replication after many years |

| Reactivated chronic hepatitis B | Elevated | − | + | 2000 – 20000 (may be higher) | Inflammation and often significant fibrosis | High risk of progression to advanced liver disease |

ALT = serum alanine aminotransferase level; anti-HBe = antibody to hepatitis B e antigen; HBeAg = hepatitis B e antigen; HBsAg = hepatitis B surface antigen; IU = international units.

Those in the immune tolerant phase, as well as those who acquire HBV infection after early childhood, may enter an immune clearance phase, associated with aminotransferase elevations and necroinflammation in the liver, with a risk of progression to cirrhosis (at a rate of 2–5.5% per year) and of hepatocellular carcinoma (at a rate of >2% per year in those with cirrhosis). Low-level immunoglobulin M antibody to hepatitis B core antigen (IgM anti-HBc) is present in serum in about 70% of such persons.

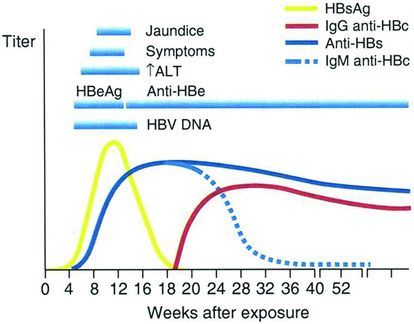

Patients enter the inactive HBsAg carrier state when biochemical improvement follows immune clearance. This improvement coincides with sequential disappearance of HBeAg and reduced HBV DNA levels (<20 000 international units [IU]/mL, or <105 copies/mL) in serum, appearance of antibody to hepatitis B e antigen (anti-HBe), and integration of the HBV genome into the host genome in infected hepatocytes (Figure 44.2). Patients in this phase are at a low risk for cirrhosis (if it has not already developed) and hepatocellular carcinoma, and those with persistently normal serum aminotransferase levels infrequently have histologically active liver disease.

Figure 44.2 Typical serologic course of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. (Adapted from the Centers For Disease Control and Prevention website, Viral Hepatitis B, Educational Materials, CDC Viral Hepatitis Brochures/Posters, Hepatitis B 101, slide 10/20. [Accessed in 2006.])

The reactivated chronic hepatitis B phase may result from infection by a pre-core mutant of HBV or spontaneous mutation of the pre-core or core promoter region of the HBV genome, with lack of synthesis of HBeAg, during the course of chronic hepatitis caused by wild-type HBV (often during the inactive HBsAg carrier phase). So-called HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B accounts for 10% of cases of chronic hepatitis B in the United States, up to 50% in Southeast Asia, and up to 90% in Mediterranean countries, reflecting in part differences in the frequencies of HBV genotypes A through J. In reactivated chronic hepatitis B, there is a rise in serum HBV DNA levels and possible progression to cirrhosis (at a rate of 8%–10% per year), particularly when additional mutations in the core gene of HBV are present. Risk factors for reactivation include male sex, advanced age, and HBV genotype C.

In patients with either HBeAg-positive or HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B, the risk of cirrhosis and of hepatocellular carcinoma correlates with the serum HBV DNA level. Other risk factors include advanced age, male sex, alcohol use, cigarette smoking, and coinfection with HCV or HDV or with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) coinfection in association with a low CD4 count.

HDV (also called the delta agent) is a defective RNA agent that only infects (either concurrently or sequentially) persons also infected with HBV. New cases of HDV infection are now infrequent in the United States and are seen primarily in immigrants from endemic areas, including Africa, Central Asia, Eastern Europe, and the Amazon region of Brazil. Most cases seen today are usually from cohorts infected years ago who survived active infection and now have cirrhosis. Acute hepatitis D infection superimposed on chronic HBV infection may result in severe chronic hepatitis, which may progress rapidly to cirrhosis and may be fatal. Patients with long-standing chronic hepatitis D and B often have inactive cirrhosis and are at risk for decompensation and hepatocellular carcinoma. The diagnosis of hepatitis D is confirmed by detection of antibody to HDV or (where available) hepatitis D antigen or HDV RNA in serum.

Treatment

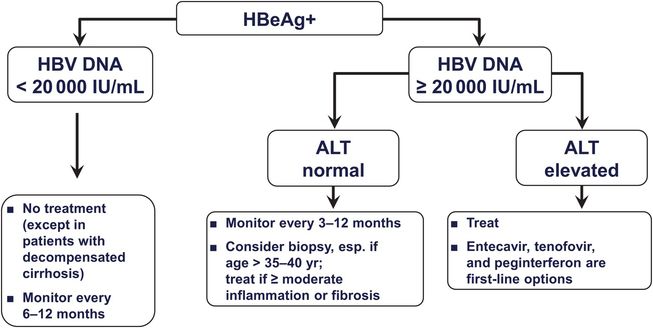

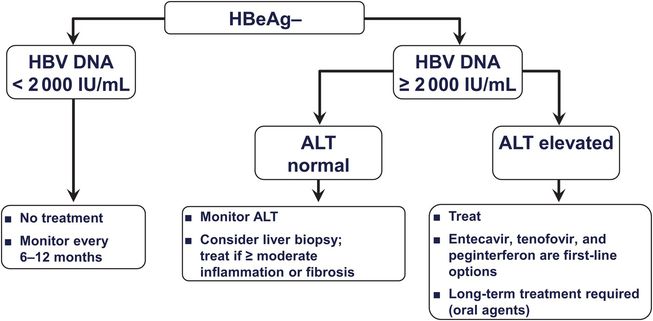

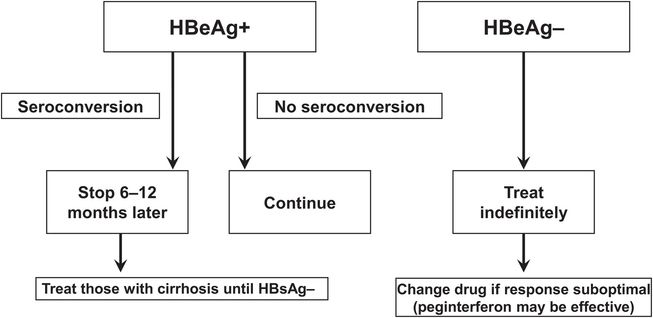

Patients with active HBV replication (HBeAg and HBV DNA [≥20 000 IU/mL, or ≥105 copies/mL] in serum and elevated aminotransferase levels) may be treated with a nucleoside or nucleotide analog or with pegylated interferon (Figure 44.3). Nucleoside and nucleotide analogs are preferred because they are better tolerated and can be taken orally. For patients who are HBeAg negative, the threshold for treatment is a serum HBV DNA level of 2000 IU/mL, or 104 copies/mL (Figure 44.4). If the threshold HBV DNA level for treatment is met but the serum ALT level is normal, treatment may still be considered in patients over age 35 to 40 if a liver biopsy specimen demonstrates a fibrosis stage of 2 of 4 (moderate) or higher. Therapy is aimed at reducing and maintaining the serum HBV DNA level to the lowest possible level, thereby leading to normalization of the ALT level and histologic improvement. An additional goal in HBeAg-positive patients is seroconversion to anti-HBe, and a few responders eventually clear HBsAg (Figure 44.5 and Table 44.3). Although nucleoside and nucleotide analogs generally have been discontinued 6 to 12 months after HBeAg-to-anti-HBe seroconversion, some patients (particularly those of Asian descent) serorevert to HBeAg after discontinuation and demonstrate a rise in HBV DNA levels and recurrence of hepatitis activity. They therefore require long-term therapy, which also is required when HBeAg-to-anti-HBe seroconversion does not occur. HBeAg-negative patients with chronic hepatitis B generally require long-term therapy as well.

Figure 44.3 Suggested treatment algorithm for HBeAg-positive patients with compensated chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV). (Adapted from Keeffe EB, Dieterich DT, Han SH, et al. A treatment algorithm for the management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: an update. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006; 4:936–962, with permission.)

Figure 44.4 Suggested treatment algorithm for HBeAg-negative patients with compensated chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV). (Adapted from Keeffe EB, Dieterich DT, Han SH, et al. A treatment algorithm for the management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: an update. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:936–962, with permission.)

Figure 44.5 Treatment end points for patients with hepatitis B e antigen-positive (HBeAg+) and hepatitis B e antigen-negative (HBeAg−) chronic hepatitis B. (Adapted from Keeffe EB, Dieterich DT, Han SH, et al. A treatment algorithm for the management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:87–106, and Marcellin P, Boyer N, Piratvisuth T, et al. Efficacy and safety of peginterferon alpha-2a (40KD) (Pegasys) in patients with chronic hepatitis B who had received prior treatment with nucleos(t)ide analogues–the Pegalam cohort. J Hepatol. 2006;44(Suppl 2):S187, with permission.) ALT = alanine aminotransferase; HBeAg = hepatitis B e antigen; HBsAg = hepatitis B surface antigen; IU = international units; Peg-IFN = pegylated alfa interferon.

| Sustained suppression of HBV replication |

| HBV DNA undetectable in serum HBeAg to anti-HBe seroconversion HBsAg to anti-HBs seroconversion |

| Remission of liver disease |

| Normalization of serum ALT levels Improvement in liver histology |

| Improvement in clinical outcome |

| Prevention of liver failure and hepatocellular carcinoma Improved survival |

ALT = alanine aminotransferase; anti-HBe = antibody to hepatitis B e antigen; anti-HBs = antibody to hepatitis B surface antigen hepatitis B virus; HBeAg = hepatitis B e antigen; HBsAg = hepatitis B surface antigen.

The available nucleoside and nucleotide analogs – entecavir, tenofovir, lamivudine, adefovir, and telbivudine – differ in efficacy and rates of resistance (Table 44.4). HBeAg-positive patients, however, achieve an HBeAg-to-anti-HBe seroconversion rate of about 20% at 1 year, with higher rates after more prolonged therapy, regardless of the drug used (Table 44.5). The preferred, most potent, first-line oral agents are entecavir and tenofovir. Entecavir, a nucleoside analog, is rarely associated with resistance unless a patient is already resistant to lamivudine. Histologic improvement is observed in 70% of treated patients and suppression of HBV DNA in serum in up to 80%. Entecavir has been reported to cause lactic acidosis when used in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Tenofovir, a nucleotide analog, also has substantial activity against HBV and is used as a first-line agent or when resistance to a nucleoside analog has developed. Like entecavir, tenofovir has a low rate of resistance when used as initial therapy. Long-term use may lead to an elevated serum creatinine level and reduced serum phosphate level (Fanconi-like syndrome) that are reversible with discontinuation of the drug.

| Agent/dose | Entecavir (nucleoside analog) 0.5 mg daily (1.0 mg daily in lamuvidine-resistant patients) | Tenofovir disoproxil (nucleotide analog) 300 mg daily | Lamivudine (nucleoside analog) 100 mg daily | Adefovir dipivoxil (nucleotide analog) 10 mg daily | Telbivudine (nucleoside analog) 600 mg daily | Peginterferon alfa-2a 180 µg SC weekly for 48 weeks |

| Advantages |